Golden Triangle (Southeast Asia)

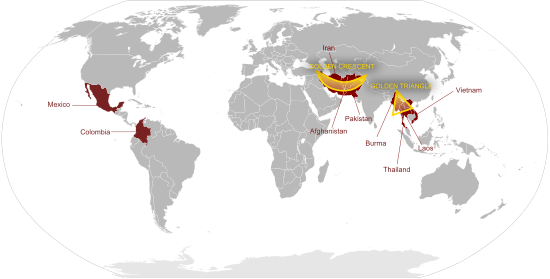

The Golden Triangle[1] is the area where the borders of Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar meet at the confluence of the Ruak and Mekong rivers.[2] The name "Golden Triangle"—coined by the CIA[3]—is commonly used more broadly to refer to an area of approximately 950,000 square kilometres (367,000 sq mi) that overlaps the mountains of the three adjacent countries.

Along with Afghanistan in the Golden Crescent, it has been one of the largest opium-producing areas of the world, since the 1950s. Most of the world's heroin came from the Golden Triangle until the early 21st century when Afghanistan became the world's largest producer.[4]

Origin

As the Chinese Communist Party gained power, they ordered ten million addicts into compulsory treatment, had dealers executed, and opium-producing regions planted with new crops. Remaining opium production shifted south of the Chinese border into the Golden Triangle region.[5]

The US-supported anti-communist Chinese resistance troops of the Kuomintang in Burma were, in effect, the forebears of the private narcotic armies operating in the "Golden Triangle." Almost all the KMT opium was sent south to Thailand.[6] Prior to the arrival of the KMT, the opium trade had already developed as a local opium economy under British colonial rule. The KMT-controlled territories made up Burma's major opium-producing region, and the shift in KMT policy allowed them to expand their control over the region's opium trade. Furthermore, Communist China's forced eradication of illicit opium cultivation in Yunnan by the early 1950s effectively handed the opium monopoly to the KMT army in the Shan states. The main consumers of the drug were the local ethnic Chinese and those across the border in Yunnan and the rest of Southeast Asia. The KMT coerced the local villagers for recruits, food and money, and exacted a heavy tax on the opium farmers. This forced the farmers to increase their production to make ends meet. One American missionary to the Lahu tribesmen of Kengtung State even testifies to the torture the KMT committed to the Lahu for failing to comply with their regulations. The annual production increased twenty-fold from 30 tons at the time of Burmese independence to 600 tons in the mid-1950s.[7]

Drug production and trafficking

Myanmar is the world's second largest producer of illicit opium, after Afghanistan[4] and has been a significant cog in the transnational drug trade since World War II.[8] According to the UNODC it is estimated that in 2005 there wеrе 430 square kilometres (167 sq mi) of opium cultivation in Myanmar.[9]

The surrender of drug warlord Khun Sa's Mong Tai Army in January 1996 was hailed by Yangon as a major counter-narcotics success. Lack of government will and ability to take on major narcotrafficking groups and lack of serious commitment against money laundering continues to hinder the overall anti-drug effort. Most of the tribespeople growing the opium poppy in Myanmar and in the Thai highlands are living below the poverty line.

In 1996, the United States Embassy in Rangoon released a "Country Commercial Guide", which states "Exports of opiates alone appear to be worth about as much as all legal exports." It goes on to say that investments in infrastructure and hotels are coming from major opiate-growing and opiate-exporting organizations and from those with close ties to these organizations.[10]

A four-year investigation concluded that Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE) was "the main channel for laundering the revenues of heroin produced and exported under the control of the Myanmar Army." In a business deal signed with the French oil giant Total in 1992, and later joined by Unocal, MOGE received a payment of $15 million. "Despite the fact that MOGE has no assets besides the limited installments of its foreign partners and makes no profit, and that the Myanmar state never had the capacity to allocate any currency credit to MOGE, the Singapore bank accounts of this company have seen the transfer of hundreds of millions of US dollars," reports François Casanier. According to a confidential MOGE file reviewed by the investigators, funds exceeding $60 million and originating from Myanmar's most renowned drug lord, Khun Sa, were channeled through the company. "Drug money is irrigating every economic activity in Myanmar, and big foreign partners are also seen by the SLORC as big shields for money laundering."[10] Banks in Rangoon offered money laundering for a 40% commission.[11]

The main player in the country's drug market is the United Wa State Army, ethnic fighters who control areas along the country's eastern border with Thailand, part of the infamous Golden Triangle. The UWSA, an ally of Myanmar's ruling military junta, was once the militant arm of the Beijing-backed Burmese Communist Party.

Poppy cultivation in the country decreased more than 80 percent from 1998 to 2006 following an eradication campaign in the Golden Triangle. Officials with the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime say opium poppy farming is now expanding. The number of hectares used to grow the crops increased 29% in 2007. A United Nations report cites corruption, poverty and a lack of government control as causes for the jump.[12]

Opium and heroin base produced in northeastern Myanmar are transported by horse and donkey caravans to refineries along the Thailand–Burma border for conversion to heroin and heroin base. Most of the finished products are shipped across the border into various towns in North Thailand and down to Bangkok for further distribution to international markets.

In the past major Thai Chinese and Burmese Chinese traffickers in Bangkok have controlled much of the foreign sales and movement of Southeast Asian heroin from Thailand, but a combination of law enforcement pressure, publicity and a regional drought has significantly reduced their role. As a consequence, many less-predominant traffickers in Bangkok and other parts of Thailand now control smaller quantities of the heroin going to international markets.

Heroin from Southeast Asia is most frequently brought to the United States by couriers, typically Thai and U.S. nationals, travelling on commercial airlines. California and Hawaii are the primary U.S. entry points for Golden Triangle heroin, but small percentages of the drug are trafficked into New York City and Washington, D.C. While Southeast Asian groups have had success in trafficking heroin to the United States, they initially had difficulty arranging street level distribution. However, with the incarceration of Asian traffickers in American prisons during the 1970s, contacts between Asian and American prisoners developed. These contacts have allowed Southeast Asian traffickers access to gangs and organizations distributing heroin at the retail level.[13]

In recent years, the production has shifted to Yaba and other forms of methamphetamine, including for export to the United States.

The Chinese Muslim Panthay are the same ethnic group as the Muslims among the Chinese Chin Haw.[14] Both are descendants of Chinese Hui Muslim immigrants from Yunnan province in China. They often work with each other in the Golden Triangle Drug Trade. Both Chinese Muslim and non-Muslim Jeen Haw and Panthay are known to be members of Triad secret societies, working with other Chinese groups in Thailand like the TeoChiew and Hakka and the 14K Triad. They engaged in the heroin trade. Ma Hseuh-fu, from Yunnan province, was one of the most prominent Jeen Haw heroin drug lords.

A Panthay from Burma, Ma Zhengwen, assisted the Han Chinese drug lord Khun Sa in selling his heroin in north Thailand.[15]:306 The Panthay monopolized opium trafficking in Burma.[15]:57 They also created secret drug routes to reach the international market with contacts to smuggle drugs from Burma via south China.[15]:400

Gallery

Golden Triangle Monument at the Mekong River

Golden Triangle Monument at the Mekong River

Notes and references

- Burmese: ရွှေတြိဂံ နယ်မြေ, pronounced [ʃwè tɹḭɡàɰ̃ nɛ̀mjè]; Thai: สามเหลี่ยมทองคำ, RTGS: sam liam thong kham, pronounced [sǎːm.lìa̯m tʰɔ̄ːŋ kʰām]; Lao: ສາມຫຼ່ຽມທອງຄຳ; Chinese: 金三角; Vietnamese: Tam giác Vàng; Khmer: តំបន់ត្រីកោណមាស, pronounced [tɑmbɑn trəy kaon mieh]

- "GOLDEN TRIANGLE". Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT). Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- O'Riordain, Aoife (22 February 2014). "Travellers Guide: The Golden Triangle". The Independent. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "Afghanistan Again Tops List of Illegal Drug Producers". The Washington Times. 12 March 2013.

- Alfred W. McCoy. "Opium History, 1858 to 1940". Archived from the original on 4 April 2007. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- McCoy, Alfred W. (1991). The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade (1st ed.). Brooklyn, N.Y.: Lawrence Hill Books. p. 173. ISBN 9781556521263.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lintner, Bertil (1992). Heroin and Highland Insurgency in the Golden Triangle. War on Drugs: Studies in the failure of US narcotic policy. Boulder, Colorado: Westview. p. 288.

- Gluckman, Ron. "Where has all the opium gone?". Ron Gluckman.

- "Facts and figures showing the reduction of opium cultivation and production..." Archived 14 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Embassy of the Union of Myanmar in Pretoria. 23 October 2005.

- Bernstein, Dennis; Leslie Kean (16 December 1996). "People of the Opiate: Myanmar's dictatorship of drugs". The Nation. 263 (20): 11–15. Archived from the original on 1 June 2004. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- Alexander Cockburn; Jeffrey St. Clair (1998). Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs and the Press. London: Verso. p. 230. ISBN 1-85984-139-2.

whiteout cockburn.

- Bouchard, Chad (12 October 2007). "Opium Cultivation Blossoms in Myanmar". Voice of America.

- "Chapter III Part 1: Drug Trafficking and Organized Crime". America's Habit. Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. 1986.

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2011). Traders of the Golden Triangle. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B006GMID5K

- Bertil Lintner (1999). Burma in Revolt: Opium and Insurgency Since 1948. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. p. 306. ISBN 974-7100-78-9. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

Li's rival Khun Sa was connected with other networks. Heroin, which had been refined in laboratories under Khun Sa's control, was marketed in northern Thailand by Ma Zhengwen, a Yunnanese Muslim (Panthay) born in Burma.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Golden Triangle. |

- Geopium: Geopolitics of Illicit Drugs in Asia. Geopium.org (since 1998) is the personal website of Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy, CNRS Research Fellow in Paris.

- Kramer, Tom, Martin Jelsma, and Tom Blickman. "Withdrawal Symptoms in the Golden Triangle: A Drugs Market in Disarray". Amsterdam: Transnational Institute, January 2009. ISBN 978-90-71007-22-4.

- "The Golden Triangle Opium Trade: An Overview" by Bertil Lintner, Chiang Mai, March 2000