Old Joseon

Gojoseon (Korean: 고조선; Hanja: 古朝鮮), originally named Joseon (Korean: 조선; Hanja: 朝鮮), was an ancient Korean Kingdom on the Korean Peninsula. The addition of Go (고, 古), meaning "ancient", is used to distinguish it from the later Joseon kingdom (1392–1897).

Gojoseon 고조선(古朝鮮) Joseon | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unknown–108 BC | |||||||||||

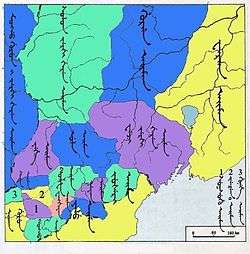

Gojoseon in 108 BC | |||||||||||

| Capital | Wanggeom | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Ye-Maek language (Koreanic) Classical Chinese | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 2333 BC - ? | Dangun (first) | ||||||||||

• ? - 194 BC | Jun | ||||||||||

• 194 BC - ? | Wi Man | ||||||||||

• ? - 108 BC | Wi Ugeo (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Ancient | ||||||||||

• Established | Unknown | ||||||||||

• First mentioned in Chinese texts | c. 700 BC | ||||||||||

• Coup by Wi Man | 194 BC | ||||||||||

• Gojoseon-Han War | 109–108 BC | ||||||||||

• Fall of Wanggeom | 108 BC | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | |

|---|---|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Gojoseon |

| McCune–Reischauer | Kochosŏn |

| IPA | [ko.dʑo.sʌn] |

| original name | |

| Hangul | |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Joseon |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chosŏn |

| IPA | [tɕo.sʌn] |

Part of a series on the |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Korea | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Prehistoric period | ||||||||

| Ancient period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Proto–Three Kingdoms period | ||||||||

| Three Kingdoms period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Northern and Southern States period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Later Three Kingdoms period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Dynastic period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Colonial period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Modern period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Manchuria |

|

|

Ancient period

|

|

Modern period |

According to the Samguk Yusa (1281), Gojoseon was established in 2333 BC by Dangun, who was said to be the offspring of a heavenly prince and a bear-woman. Though Dangun is a mythological figure for whom no concrete evidence has been found,[1] the account has played an important role in developing Korean identity. Today, the founding date of Gojoseon is officially celebrated as the National Foundation Day in North Korea[2] and South Korea.

Some ancient sources allege that in the 12th century BC the Chinese nobleman and sage Gija (also known as Jizi), a man belonging to the royal family of the Shang dynasty of China, immigrated to the Korean Peninsula and founded Gija Joseon.[3][4] This myth is widely discredited today due to contradicting evidence, and it is no longer considered a part of Korea's mythical tradition.

Gojoseon was first mentioned in ancient Chinese records in the early 7th century BC.[5] During its early phase, the capital of Gojoseon was located in present-day Liaoning; around 400 BC, it was moved to Pyongyang, while in the south of the Korean Peninsula, the Jin state arose by the 3rd century BC.[6]

In 108 BC, the Han dynasty of China invaded and conquered Wiman Joseon. The Han established four commanderies to administer the Gojoseon territory. The area was later conquered by Goguryeo in 313 AD.

Founding myths

There are three different main founding myths concerning Gojoseon, which revolve around Dangun, Gija, or Wi Man.[7]

Dangun myth

The myths revolving around Dangun were recorded in the much-later Korean work Samguk Yusa of the 13th century.[8] This work states that Dangun, the offspring of a heavenly prince and a bear-woman, founded Gojoseon in 2333 BC, only to be succeeded by Gija (Qizi) after King Wu of Zhou had placed him onto the throne in 1122 BC.[8] A similar account is found in Jewang Ungi. According to the legend, the Lord of Heaven, Hwanin had a son, Hwanung, who descended to Baekdu Mountain and founded the city of Shinsi. Then a bear and a tiger came to Hwanung and said that they wanted to become people. Hwuanung said to them that if they went in a cave and lived there for 100 days while only eating mugwort and garlic he will change them into human beings. However, about halfway through the 100 days the tiger gave up and ran out of the cave. On the other hand, the bear successfully restrained herself and became a beautiful woman called Ungnyeo (웅녀, 熊女). Hwanung later married Ungnyeo, and she gave birth to Dangun.[9]

While the Dangun story is considered to be a myth,[1] it is believed it is a mythical synthesis of a series of historical events relating to the founding of Gojoseon.[10] There are various theories on the origin of this myth.[11] Seo and Kang (2002) believe the Dangun myth is based on integration of two different tribes, an invasive sky-worshipping Bronze Age tribe and a native bear-worshipping neolithic tribe, that led to the foundation of Gojoseon.[12] Lee K. B. (1984) believes 'Dangun-wanggeom' was a title borne by successive leaders of Gojoseon.[13]

Dangun is said to have founded Gojoseon around 2333 BC, based on the descriptions of the Samgungnyusa, Jewang Ungi, Dongguk Tonggam and the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty.[14] The date differs among historical sources, although all of them put it during the mythical Emperor Yao's reign (traditional dates: 2357 BC? – 2256 BC?). Samgungnyusa says Dangun ascended to the throne in the 50th year of the legendary Yao's reign, Annals of the King Sejong says the first year, and Dongguk Tonggam says the 25th year.[15]

Gija myth

Gija, a man from the period of the Shang dynasty, allegedly fled to the Korean peninsula in 1122 BC during the fall of the Shang to the Zhou dynasty and founded Gija Joseon.[16] Most experts believe Gija's relation to Gojoseon is a Chinese fabrication and Gija has nothing to do with Gojoseon.[11] In the past, the earliest surviving Chinese record, Records of the Three Kingdoms, recognized Gija Joseon. The Dongsa Gangmok of 1778 described Gija's activities and contributions in Gojoseon. The records of Gija refer to Eight Prohibitions (Korean: 범금팔조; Hanja: 犯禁八條), that are recorded by the Book of Han and evidence a hierarchical society and legal protection of private property.[17]

In pre-modern Korea, Gija represented the authenticating presence of Chinese civilization, and until the 12th century, Koreans commonly believed that Dangun bestowed upon Korea its people and basic culture, while Gija gave Korea its high culture—and presumably, standing as a legitimate civilisation.[18]

However, in the modern era Gija's place has diminished to the point of near extinction.[18] Many experts deny its existence for various reasons, mainly due to contradicting archaeological evidence and anachronistic historical evidence.[19] They point to the Bamboo Annals and the Analects of Confucius, which were among the first works to mention Gija, but do not mention his migration to Gojoseon.[20] The myth that Gija migrated to Korea is believed to have been made up by Han Dynasty in order to justify its conquest of Korea.[21]

Wi Man

Wi Man was a military officer of the Yan of northeastern China, who fled to the northern Korean peninsula in 195 BC from the encroaching Han dynasty.[8] He founded a principality with Wanggeom-seong as capital, which is thought to be on the region of present-day Pyongyang.[8] The 3rd-century Chinese text Weilüe of the Sanguozhi recorded that Wiman usurped King Jun and thus took kingship over Gojoseon.[8]

Academic perspectives

Gojoseon history can be divided into three phases, Dangun, Gija and Wiman Joseon.[22]

- Kang & Macmillan (1980), Sohn et al. (1970), Kim J.B. (1980), Han W.K. (1970), Yun N. H. (1985), Lee K.B. (1984), Lee J.B. (1987) viewed the Dangun myth as a native product of proto-Koreans, although it is not always associated with Gojoseon.[22] Kim J.B. (1987) rejected the Dangun myth's association with Gojoseon and pushes it further back to the Neolithic period. Sohn et al. (1970) suggested Dangun myth is associated with the Dongyi, whom they viewed as the ancestors of Koreans. Kim C. (1948) suggested the Dangun myth had a Chinese origin, tracing it to a Han Dynasty tomb in the Shandong peninsula.

- Gardiner (1969), Henderson (1959), McCune(1962), Han W.K. (1970), Sohn et al. (1970), Lee K.B. (1984) dismissed the Gija myth as a Chinese fabrication.[22] On the other hand, Hatada (1969), to give Gojoseon a Chinese identity, exclusively ascribed to the Gija myth.

- Kim C.W. (1966), Han W.K. (1970), Choi M.L. (1983, 1984, 1985, 1992), Han W.K. (1984), Kim J.B. (1987), Lee K.B. (1984) accepted Wiman as a historical figure.[22] Gardiner (1969) questioned authenticity of the Wiman myth, although he mentioned there were interaction between Gojoseon and the Han Dynasty and social unrest in the area during that time period.[22]

State formation

Gojoseon is first found in contemporaneous historical records of the early 7th century BCE as located around Bohai Bay and trading with Qi (齊) of China.[23] The Zhanguoce, Shanhaijing, and Shiji—containing some of its earliest records—refers to Joseon as a region, until the text Shiji began referring it as a country from 195 BC onwards.[24]

By the 4th century BC, other states with defined political structures developed in the areas of the earlier Bronze Age "walled-town states"; Gojoseon was the most advanced of them in the peninsular region.[6] The city-state expanded by incorporating other neighboring city-states by alliance or military conquest. Thus, a vast confederation of political entities between the Taedong and Liao rivers was formed. As Gojoseon evolved, so did the title and function of the leader, who came to be designated as "king" (Han), in the tradition of the Zhou dynasty, around the same time as the Yan (燕) leader. Records of that time mention the hostility between the feudal state in Northern China and the "confederated" kingdom of Gojoseon, and notably, a plan to attack the Yan beyond the Liao River frontier. The confrontation led to the decline and eventual downfall of Gojoseon, described in Yan records as "arrogant" and "cruel". But the ancient kingdom also appears as a prosperous Bronze Age civilisation, with a complex social structure, including a class of horse-riding warriors who contributed to the development of Gojoseon, particularly the northern expansion[26] into most of the Liaodong basin.

Around 300 BC, Gojoseon lost significant western territory after a war with the Yan state, but this indicates Gojoseon was already a large enough state that it could wage war against Yan and survive the loss of 2000 li (800 kilometres) of territory.[17] Gojoseon is thought to have relocated its capital to the Pyongyang region around this time.

Wiman Joseon and fall

In 195 BC, King Jun appointed a refugee from Yan, Wi Man, to guard the frontier.[27] Wi Man later rebelled in 194 BC and usurped the throne of Gojoseon. King Jun fled to Jin in the south of the Korean Peninsula.[28]

In 109 BC, Emperor Wu of Han invaded near the Liao River.[28] A conflict would erupt in 109 BC, when Wiman's grandson King Ugeo (우거왕, hanja: 右渠王) refused to let Jin's ambassadors through his territory in order to reach the Han dynasty. When Emperor Wu sent an ambassador (涉何) to Wanggeom-seong to negotiate right of passage with King Ugeo, King Ugeo refused and had a general escort him back to Han territory—but when they got close to Han borders, he assassinated the general and claimed to Emperor Wu that he had defeated Joseon in battle, and Emperor Wu, unaware of his deception, made him the military commander of the Commandery of Liaodong. King Ugeo, offended, made a raid on Liaodong and killed him.

In response, Emperor Wu commissioned a two-pronged attack, one by land and one by sea, against Gojoseon.[28] The two forces attacking Gojoseon were unable to coordinate well with each other and eventually suffered large losses. Eventually the commands were merged, and Wanggeom fell in 108 BC. Han took over the Gojoseon lands and established Four Commanderies of Han in the western part of former Gojoseon area.[29]

The Gojoseon disintegrated by 1st century BCE as it gradually lost the control of its former fiefs. As Gojoseon lost control of its confederacy, many successor states sprang from its former territory, such as Buyeo, Okjeo, Dongye. Goguryeo and Baekje evolved from Buyeo.

Culture

Around 2000 BCE, a new pottery culture of painted and chiselled design is found. These people practised agriculture in a settled communal life, probably organised into familial clans. Rectangular huts and increasingly larger dolmen burial sites are found throughout the peninsula. Bronze daggers and mirrors have been excavated, and there is archaeological evidence of small walled-town states in this period.[26][30] Dolmens and bronze daggers found in the area are uniquely Korean and cannot be found in China. A few dolmens are found in China, mostly in the Shandong province.[31]

Mumun pottery

In the Mumun pottery period (1500 BC – 300 BCE), plain coarse pottery replaced earlier comb-pattern wares, possibly as a result of the influence of new populations migrating to Korea from Manchuria and Siberia. This type of pottery typically has thicker walls and displays a wider variety of shapes, indicating improvements in kiln technology.[6] This period is sometimes called the "Korean Bronze Age", but bronze artifacts are relatively rare and regionalised until the 7th century BC.

Rice cultivation

Sometime around 1200 BC to 900 BC, rice cultivation spread to Korea from China and Manchuria. The people also farmed native grains such as millet and barley, and domesticated livestock.[32]

Bronze tools

The beginning of the Bronze Age on the peninsula is usually said to be 1000 BC, but estimates range from the 13th to 8th centuries.[33] Although the Korean Bronze Age culture derives from the Liaoning and Manchuria, it exhibits unique typology and styles, especially in ritual objects.[34]

By the 7th century BC, a Bronze Age material culture with influences from Manchuria, eastern Mongolia as well as Siberia and Scythian bronze styles, flourished on the peninsula. Korean bronzes contain a higher percentage of zinc than those of the neighbouring bronze cultures. Bronze artifacts, found most frequently in burial sites, consist mainly of swords, spears, daggers, small bells, and mirrors decorated with geometric patterns.[6][35]

Gojoseon's development seems linked to the adoption of bronze technology. Its singularity finds its most notable expression in the idiosyncratic type of bronze swords, or "mandolin-shaped daggers" (비파형동검, 琵琶形銅劍). The mandolin-shape dagger is found in the regions of Liaoning, Hebei, and Manchuria down to the Korean Peninsula. It suggests the existence of Gojoseon dominions. Remarkably, the shape of the "mandolin" dagger of Gojoseon differs significantly from the sword artifacts found in China.

Dolmen tombs

Megalithic dolmens appear in Korean peninsula and Manchuria around 2000 BC to 400 BC.[36][37] Around 900 BC, burial practices become more elaborate, a reflection of increasing social stratification. Goindol, the dolmen tombs in Korea and Manchuria, formed of upright stones supporting a horizontal slab, are more numerous in Korea than in other parts of East Asia. Other new forms of burial are stone cists (underground burial chambers lined with stone) and earthenware jar coffins. The bronze objects, pottery, and jade ornaments recovered from dolmens and stone cists indicate that such tombs were reserved for the elite class.[6][38]

Around the 6th century BC, burnished red wares, made of a fine iron-rich clay and characterised by a smooth, lustrous surface, appear in dolmen tombs, as well as in domestic bowls and cups.[6]

Iron culture

Around this time, the state of Jin occupied the southern part of the Korean peninsula. Very little is known about this state except it was the apparent predecessor to the Samhan confederacies.

Around 300 BC, iron technology was introduced into Korea from Yan state. Iron was produced locally in the southern part of the peninsula by the 2nd century BCE. According to Chinese accounts, iron from the lower Nakdong River in the southeast was valued throughout the peninsula and Japan.[6]

Proto–Three Kingdoms of Korea

Numerous small states and confederations arose from the remnants of Gojoseon, including Goguryeo, the Buyeo kingdom, Jeon-Joseon, Okjeo, and Dongye. Three of the Chinese commanderies fell to local resistance within a few decades, but the last, Nakrang, remained an important commercial and cultural outpost until it was destroyed by the expanding Goguryeo in 313 AD.

Jun of Gojoseon is said to have fled to the state of Jin in the southern Korean Peninsula. Jin developed into the Samhan confederacies, the beginnings of Baekje and Silla, continuing to absorb migration from the north. The Samhan confederacies were Mahan, Jinhan, and Byeonhan. King Jun ruled Mahan, which was eventually annexed by Baekje. Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla gradually grew into the Three Kingdoms of Korea that dominated the entire peninsula by around the 4th century.

See also

Notes

-

- Seth, Michael J. (2010). A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 443. ISBN 978-0-7425-6717-7.

- "An extreme manifestation of nationalism and the family cult was the revival of interest in Tangun, the mythical founder of the first Korean state... Most textbooks and professional historians, however, treat him as a myth."

- Stark, Miriam T. (2008). Archaeology of Asia. John Wiley & Sons. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-4051-5303-4.

- "Although Kija may have truly existed as a historical figure, Tangun is more problematical."

- Schmid, Andre (2013). Korea Between Empires. Columbia University Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-231-50630-4.

- "Most [Korean historians] treat the [Tangun] myth as a later creation."

- Peterson, Mark (2009). Brief History of Korea. Infobase Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4381-2738-5.

- "The Tangun myth became more popular with groups that wanted Korea to be independent; the Kija myth was more useful to those who wanted to show that Korea had a strong affinity to China."

- Hulbert, H. B. (2014). The History of Korea. Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-317-84941-4.

- "If a choice is to be made between them, one is faced with the fact that the Tangun, with his supernatural origin, is more clearly a mythological figure than Kija."

- uriminzokkiri 우리민족끼리 official website of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea

- Kim, Djun Kil (2014). The History of Korea, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. p. 8. ISBN 9781610695824.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne (2013). Pre-Modern East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Volume I: To 1800. Cengage Learning. p. 100. ISBN 9781285546230.

- Peterson & Margulies 2009, p. 6.

- "Timeline of Art and History, Korea, 1000 BC – 1 AD". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Barnes, Gina (2000). State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives. Richmond: Curzon. p. 10. ISBN 9780700713233.

- Barnes, Gina (2000). State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives. Richmond: Curzon. p. 11. ISBN 9780700713233.

- Samguk Yusa《삼국유사》(三國遺事)

- 고조선(古朝鮮). Encyclopædia Britannica( Korean) (in Korean).

- Barnes 2001, pp. 9–14.

- 서강 2002.

- Lee 1984.

- 국학원 제24회 학술회의 - 단기 연호 어떻게 볼 것인가 - 단기가 최초로 산정된 것은 《동국통감》으로 요임금 즉위 25년 무진년을 기준으로 삼았다. 《동국통감》〈외기〉 의 주석에는 다음과 같은 해석이 실려있다. - 古記云, 檀君與堯竝立於戊辰, 虞夏至商武丁八年乙未, 入阿斯達山爲神, 享壽千四百十八年. 此說可疑今按, 堯之立在上元甲子甲辰之歲, 而檀君之立在後二十五年戊辰, 則曰與堯竝立者非也. 이에 대한 한글 해석은 네이버 지식백과 국역 동국통감(국역:세종대왕기념사업회) 에서 확인할 수 있다.

- Yoon, N.-H. (윤내현), The Location and Transfer of Go-Chosun's Capital (고조선의 도읍 위치와 그 이동), 단군학연구, 7, 207–38 (2002)

- Barnes 2001, pp. 9–10.

- "Daum 요청하신 페이지의 사용권한이 없습니다". status.daum.net.

- Kyung Moon hwang, "A History of Korea, An Episodic Narrative", 2010, p. 4

- "古朝鮮과 琵琶形銅劍의 問題". 단군학연구 (12): 5–30. June 16, 2005 – via www.dbpia.co.kr.

- "기자조선". terms.naver.com.

- Shim, Jae-Hoon (2002). "A new understanding of Kija Chosŏn as a historical anachronism". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 62 (2): 271–305. doi:10.2307/4126600. JSTOR 4126600.

- Cited in Barnes, Gina (2014). State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives. New York: Routledge. pp. 10–13. ISBN 9780700713233.

- 고조선 (in Korean). Naver/Doosan Encyclopedia.

- Barnes, Gina (2000). State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives. Richmond: Curzon. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9780700713233.

- "Korea's Place in the Sun". The New York Times.

- Academy of Korean Studies, The Review of Korean Studies, vol. 10권,3–4, 2007, p. 222

- Lee Injae, Owen Miller, Park Jinhoon, Yi Hyun-Hae, Korean History in Maps, Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 20

- Jae-eun Kang, The Land of Scholars: Two Thousand Years of Korean Confucianism, Homa & Sekey Books, 2006, pp. 28–31

- "North Korea - THE ORIGINS OF THE KOREAN NATION". www.country-data.com.

- Joussaume, Roger (1988). Dolmens for the dead : megalith-building throughout the world. London: Batsford. ISBN 0713453699. OCLC 15593505.

- "Timeline of Art and History". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- "청동기문화". terms.naver.com.

- 김정배, 고조선 연구의 사적 고찰 (Historical Survey on Research of Kochosun), 단군학연구, 7, 185 - 206 (2002)

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Arts of Korea, Bronze Age Objects

- "A Tripolar Approach to East Asian History" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-04. Retrieved 2015-04-29.

- Holcombe, Charles (December 16, 2011). A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521515955 – via Google Books.

- Unesco.

Bibliography

- Barnes, Gina Lee (2001). State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1323-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Ki-Baik (1984). A New History of Korea. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-61575-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peterson, Mark; Margulies, Phillip (2009). A brief history of Korea. New York, NY: Facts On File. ISBN 9781438127385.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- 서, 의식; 강, 봉룡 (2002). 뿌리 깊은 한국사 샘이 깊은 이야기 1 : 고조선·삼국 [Deep-rooted Korean History 1 : Gojoseon·Three Kingdoms] (in Korean). 솔. ISBN 978-8981335366.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)