Gerald Desmond Bridge

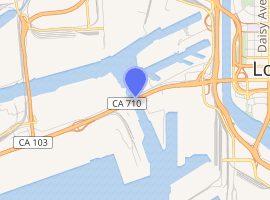

The Gerald Desmond Bridge is a through arch bridge that carries four lanes of Ocean Boulevard from Interstate 710 in Long Beach, California, west across the Back Channel to Terminal Island. The bridge is named after Gerald Desmond, a prominent civic leader and a former city attorney for the City of Long Beach.

Gerald Desmond Bridge | |

|---|---|

The 1968 Gerald Desmond Bridge spans the Back Channel, connecting Long Beach with Terminal Island. | |

| Coordinates | 33°45′52″N 118°13′16″W |

| Carries | 5 lanes of Ocean Blvd between |

| Crosses | Back Channel |

| Locale | Terminal Island and Long Beach, California |

| Named for | Gerald Desmond |

| Owner | Port of Long Beach |

| NBI | 53C0065 |

| Preceded by | 1944 pontoon bridge |

| Followed by | Cable-stayed span |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | through arch bridge |

| Material | Steel |

| Total length | 5,134 ft (1,565 m) |

| Width | 67.3 ft (21 m) |

| Height | 250 ft (76 m) |

| Longest span | 527 ft (161 m) |

| Clearance above | 18.4 ft (6 m) |

| Clearance below | 155 ft (47 m) |

| History | |

| Designer | Moffatt & Nichol |

| Constructed by | Bethlehem Steel |

| Construction start | October 19, 1965 |

| Construction end | June 1968 |

| Construction cost | US$12,700,000 (equivalent to $93,370,000 in 2019) |

| Rebuilt | 1995–2000 |

| Closed | 2020 (scheduled) |

| Replaces | 1944 pontoon bridge |

| Replaced by | Cable-stayed span |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 62,057 (2012) |

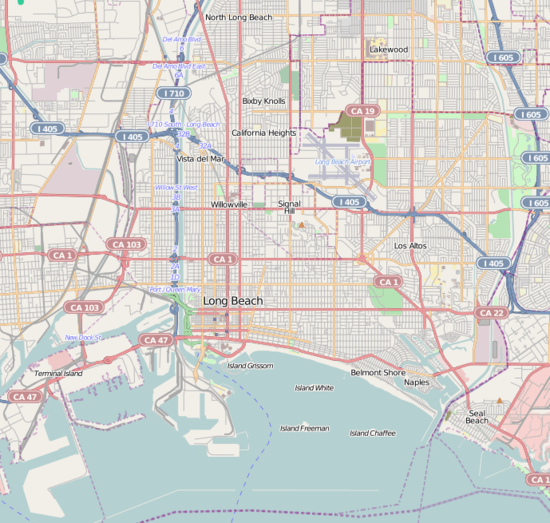

Gerald Desmond Bridge Location in Long Beach, California | |

Historical crossings

Prior to 1944, the only road access to Terminal Island was via Badger Avenue (later Henry Ford Avenue, after an assembly plant that was built on the island) over the Henry Ford Bridge.

1944 pontoon bridge

The first bridge linking the eastern end of Terminal Island and Long Beach was an unnamed "temporary" pontoon bridge constructed during World War II to accommodate traffic resulting from the expansion of the Long Beach Naval Shipyard. The pontoon bridge was intended to last six months, but was not replaced until 1968, 24 years after it had opened. Depending on the level of the tide, road traffic had to descend 17 to 25 feet (5.2 to 7.6 m) below the level on the shore. When marine traffic required the bridge to open, traffic delays of up to 15 minutes could occur.[1] An estimate of seven people died after driving off the pontoon bridge.[1][2]

1968 through-arch

The 1968 through-arch bridge was designed by Moffatt & Nichol[3] Engineers and was constructed by Bethlehem Steel[4] as a replacement for the World War II-era pontoon bridge.[5] Gerald Desmond served as City Attorney for Long Beach and played a significant role in obtaining tideland oil funds which helped finance the bridge that would later bear his name. Desmond died in office at age 48 of kidney cancer.[6] One year after Desmond's death in January 1964, ground-breaking for the construction of the new bridge occurred on October 19, 1965, and it was completed in June 1968. Desmond's son, also named Gerald, sank the final "golden" bolt.[6]

Design

It has a 527-foot-long (161 m) suspended main span and a 155-foot (47 m) vertical clearance spanning the Cerritos Channel. The western terminus of the bridge is on the east side of Terminal Island; the eastern terminus is close to downtown Long Beach. The bridge separates the inner harbor (north of the bridge) of the Port of Long Beach from the middle harbor.

Seismic retrofitting

The bridge was retrofitted with vibration isolators and additional foundation work (widening footings and adding pilings) was performed to upgrade the seismic resistance from 1996–97 prior to the transfer of ownership from the Port of Long Beach to Caltrans.[7]

Issues

At the time of its completion in 1968, traffic was projected to be modest and mainly limited to workers commuting to jobs at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard. When the Long Beach NSY was closed in 1997, that land was converted and served as home to one of the busiest container terminals in the United States, resulting in greater cargo truck and marine traffic. By some estimates, truck traffic across the bridge tripled in the years following the closure of the Long Beach NSY.[8] By 2010, the 155-foot (47 m) vertical clearance of the 1968 bridge was one of the lowest for a commercial seaport, especially at the Port of Long Beach, which remains one of the busiest container ports in the United States.[9] In addition, the bridge was not designed for the traffic it carried (62,000 vehicles daily in 2012), and the added stress was causing pieces of concrete to fall from the bridge's underside, forcing the Port of Long Beach to install nylon mesh "diapers" in 2004 to catch these chunks.[8] Studies to widen the bridge were funded in 1987.[10] Caltrans rated the structural sufficiency of the Desmond Bridge at 43 points out of possible 100 in 2007.[11]

Also, since the 1968 bridge roadway lacks emergency/breakdown lanes, multiple lanes would be shut down in the event of an accident, snarling traffic.[12] Other deficiencies cited include the steep approach grades (5.5 percent on the west side and 6 percent on the east side)[13]

Competition in the marine shipping industry meant shipping companies were interested in boosting operating efficiency, mainly by building ever-larger container ships. The Gerald Desmond Bridge became a barrier for large ships entering the Inner Harbor at Long Beach, with its restrictive 155-foot (47 m) vertical clearance. This restrictive vertical clearance was cited as a factor in an observed drop in the Port of Long Beach's share of United States container imports. According to U.S. census data, the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles handled 32% of U.S. container imports in 2013, down from 39% in 2002.[14] Port officials estimated that 10% of all waterborne cargo in the United States passed over the Desmond Bridge (either going to or coming from the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles) in 2004,[8] raising the estimate to 15% by 2010.[11]

In March 2012, the insufficient vertical clearance of the bridge prevented passage of the 12,562 TEU MSC Fabiola, the largest container ship ever to enter the Port of Long Beach. The height restriction prevented the ship from docking at the Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) dock; it docked at the Hanjin terminal instead.[15]

_from_north_looking_south-southeast_crop.jpg)

Cable-stayed replacement

Gerald Desmond Bridge Replacement | |

|---|---|

Rendering of the replacement bridge | |

| Coordinates | 33°45′52″N 118°13′16″W |

| Carries | 6 lanes of |

| Crosses | Back Channel |

| Locale | Terminal Island and Long Beach, California |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Cable-stayed bridge |

| Total length | 8,800 ft (2,682 m) |

| Height | 515 ft (157 m) |

| Longest span | 1,000 ft (305 m) |

| Clearance below | 205 ft (62 m) |

| History | |

| Architect | Brownlie Ernst and Marks |

| Designer | Arup |

| Engineering design by | Arup |

| Constructed by | Shimmick/FCC/Impreglio (SFI) Joint Venture |

| Construction start | January 8, 2013 |

| Construction end | est. 2020[16] |

| Construction cost | est. US$1,500,000,000 (equivalent to $1,617,930,000 in 2019) |

| |

The 1968 steel arch bridge developed numerous issues (detailed above), and the Port of Long Beach suggested it would be more economical to replace the bridge. After several years of studies, a cable-stayed bridge with 205 feet (62 m) of vertical clearance to be built north of the existing bridge was identified as the preferred alternative in the final environmental impact report (2010 FEIR).[13] The new bridge will allow access to the port for the tallest container ships, and will be the first long-span cable-stayed bridge in California, and the first and only cable-stayed bridge in the Los Angeles metropolitan area.[17] For the bridge to be so tall, long approaches will be required to allow trucks to cross.[18] A joint venture of Parsons Transportation Group and HNTB performed preliminary engineering for the main span and the approaches. Earlier reports had studied and discarded various alternatives, including an alternative alignment with a new bridge south of the existing bridge, rehabilitation of the existing bridge, and a tunnel instead of an elevated bridge.[13]

Design

The current roadway is four lanes (two in each direction) with a fifth climbing lane on each end. The replacement bridge will carry a six-lane roadway with emergency lanes on each side, and the grade will decrease by building a longer approach, despite the higher vertical clearance over the Back Channel; the planned improvements will bring the bridge up to current freeway standards.[19] The replacement bridge will also carry a pedestrian/bike path and observation decks over the water along the south side of the bridge. The path is named for Mark Bixby, a longtime proponent of adding bike lanes to the replacement for the Gerald Desmond Bridge[20][21] and a descendant of one of the original founders of Long Beach. Mark Bixby died in a March 2011 plane crash at the Long Beach Airport.[22]

Ocean Boulevard, currently carried by the 1968 bridge, is operated by the City of Long Beach. When the replacement bridge is completed, the roadway it carries will be redesignated the western extension of I-710, extending to its intersection with State Route 47, and it will become the responsibility of Caltrans, District 7.[19]

From west to east, the new bridge will span a total of 8,800 feet (2,700 m), consisting of:[23]

- The 2,800 ft (850 m) West Approach (3,117 ft (950 m) in the 2010 FEIR)[13]

- The 2,000 ft (610 m) cable-stayed span, with a 1,000 ft (300 m) Main Span flanked by two 500 ft (150 m) Back Spans

- The 3,600 ft (1,100 m) East Approach (3,035 ft (925 m) in the 2010 FEIR)[13]

By extending the approach structures, approach grades are reduced to no more than 5 percent.[13]

As the tallest structure in the area, the 2018 cable-stayed bridge will be a prominent addition to the Long Beach skyline.[24]

Construction

.jpg)

The replacement bridge was unanimously approved by the City of Long Beach in late September 2010.[25] A project launch meeting was held at the Port of Long Beach on November 22, 2010, attended by Long Beach Mayor Bob Foster, U.S. Representatives Dana Rohrabacher and Laura Richardson, Senator Alan Lowenthal and Caltrans Director Cindy McKim.[19]

Caltrans, Port of Long Beach, and Metro officials reviewed seven potential engineering and construction firms, selecting four as qualified final lead bidders:[26]

- Dragados USA (leading a joint venture of CC Myers, Dragados USA, Figg Bridge Engineers and Jacobs Engineering Group)

- Kiewit Infrastructure West (leading a joint venture of Kiewit and T.Y. Lin International)

- Shimmick Construction Company (leading a joint venture of Shimmick, FCC Construction/Impreglio and Arup/Biggs Cardosa)

- Skanska (leading a joint venture of Skanska/Trayor/Massman, Buckland & Taylor, and CH2M HILL Engineers)

Three of the pre-qualified bidders submitted proposals by March 2012, with Kiewit dropping out at the bid stage.[27] In May 2012, the Long Beach Board of Harbor Commissioners approved Port of Long Beach staff’s recommendation that the “best value” design-build proposal to replace the Gerald Desmond Bridge was submitted by the SFI joint venture team, comprising Shimmick Construction Company Inc., FCC Construction S.A. and Impregilo S.p.A.,[28] and the contract was awarded to the SFI JV in July 2012.[29] Major participants in the joint venture also include Arup North America Ltd. and Biggs Cardosa Associates Inc.[30]

The project is to be completed as a design-build in contrast to the traditional design-bid-build used typically in infrastructure improvement.[30]

During the groundbreaking ceremony on January 8, 2013, two helicopters hovered 515 feet (157 m) above ground level, illustrating the height of the two cable towers for the planned replacement bridge.[31]

The project was originally estimated to cost $800 million in 2008.[32] By 2010, costs had increased to $1.1 billion,[25] and funding identified in 2010 for the replacement bridge included $500 million contributed by Caltrans, $300 million contributed by the USDOT, $114 million from the Port of Long Beach, and $28 million from Metro.[19] As of 2016, the current project estimate is $1.5 billion.[17] Traffic is scheduled to open in both directions in 2020.[16]

Construction issues

The new bridge was delayed shortly after breaking ground. The new piers were delayed by the relocation and/or removal of numerous old and active oil wells and utility lines, which prevented foundation work from beginning. The bridge is located in the midst of the Wilmington Oil Field, one of the most prolific oil-producing fields located in the United States.[33]

Another part of the cost increase and schedule delay is attributed to a 2013 redesign of the support towers.[34] Caltrans and the Port of Long Beach required the tower redesign, executed by the SFI joint venture, allegedly to ensure seismic safety and to preserve long term structural integrity. The redesign set the estimated completion of the bridge back by 12 to 18 months.[35] Other cost increases are attributed to extra oversight required by innovative, yet contractually compliant products and materials proposed by the designers of the replacement bridge.[17]

The roadway for the approach structures will be supported during construction by an underlane self-launched movable scaffold system (MSS),[36] and it will be the first project in California to use a MSS.[37] The MSS is designed to bridge the 235 ft (72 m) span between piers and will support the concrete as it is poured for each span. Once the concrete has cured, the MSS will move to the next pier and repeat the pour. The orange MSS is being used on the western (Terminal Island) approach, and a similar blue MSS is being used on the eastern approach.[37]

Construction progress

By October 2014, work had started on the pilings which would serve as foundations for the new bridge's piers.[38] The two cable-stay support towers were started in March (eastern tower) and April 2015 (western tower).[36] Approach spans were underway by April 2016.[37] By August 2016, the project had passed the halfway mark, and the two cable support towers were already more than 200 ft (61 m) high.[39] On December 5, 2017, a "topping-out" ceremony was held to celebrate the completion of the two cable support towers.[16]

Popular culture

The 1944 pontoon bridge was featured in a chase scene appearing in the 1963 film It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.[1][40]

The 1968 arch bridge had a featured role in the film Head, featuring rock group The Monkees, released in 1968. The first scene of the film features the actual dedication ceremony for the bridge, which is interrupted by the Monkees running into the middle of the ceremony and Micky Dolenz jumping off the bridge. At the conclusion of the film, the Monkees return to the bridge and each of them jumps from it.

Elysian Freeway Bridge, based on the 1968 arch bridge is also featured in the 2013 video game Grand Theft Auto V . It carries the Elysian Fields Freeway in-game.

See also

- Vincent Thomas Bridge

- Burlington Skyway, a bridge of similar design in Ontario

- John Blatnik Bridge, a bridge of similar design in Minnesota

References

- Harvey, Steve (October 3, 2010). "Bridge is afloat on the pages of history". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Waldie, D. J. (June 3, 2013). "The Bridges of Terminal Island". KCET. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Husky, Brian. "Rail & Bridge Services". M&N. Archived from the original on August 4, 2014.

- "Slender but sturdy". Palos Verdes Peninsula News. February 1, 1967. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

SLENDER BUT STURDY - Slender spans of steel connect the lofty piers of the Gerald Desmond bridge, marking near completion of the eastern approach which will form the vital link between the Port of Long Beach and Terminal Island. This consists of a fabricated steel plate girder structure extending 1813 ft. from ground level to a height of 141 ft. Bethlehem Steel bridgemen are now erecting the bridge’s east approach anchor arms which will support the cantilevered portion, or main channel span. To date, Bethlehem, prime contractor for the $12.7 million project, has erected over 2400 tons of steel for the east approach. Shorter suspended girders were fabricated at Bethlehen’s Torrance works. The new bridge will be a three-span, tied-arch truss with welded-plate-girder approaches and an overall length of 6000 feet. Highest part of the arch will be 250 feet with the main deck clearing the entrance channel by 160 feet. It will link the Ocean Boulevard bridge, which crosses the Los Angeles River with Seaside Boulevard on Terminal Island.

- Baldwin, Jack O. (June 7, 1968). "Desmond Bridge is Dedicated". Long Beach Independent. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- Haldane, David (June 20, 1985). "Son of a Bridge, If It Isn't Gerald Desmond". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- "Seismic Work Will Force Weekend Closure of Desmond Bridge on Terminal Island". Los Angeles Times. April 24, 1997. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- Daniels, Cynthia (March 25, 2004). "Terminal Island Cargo Has Outgrown Old Bridge". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Ceasar, Stephen (November 23, 2010). "Long Beach bridge at the end of its lifespan". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Murphy, Dean (May 28, 1987). "Overpasses, Bridge Work Proposed in Harbor Area". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- White, Ronald D. (February 9, 2010). "Bridge poses a tight squeeze for cargo ships". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- White, Ronald D. (February 5, 2010). "Plan to replace bridge at Port of Long Beach progresses". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Parsons–HNTB Joint Venture (July 2010). Gerald Desmond Bridge Replacement Project: Final Environmental Impact Report / Environmental Assessment & Application Summary Report (PDF) (Report). Port of Long Beach and Caltrans. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Kirkham, Chris; Khouri, Andrew (June 2, 2015). "LA., Long Beach ports losing to rivals amid struggle with giant ships". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Porter, Janet (March 6, 2012). "Long Beach prepares for Pacific ultra-large boxship switch". Lloyd's List. Lloyd's. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- Ruiz, Jason (December 6, 2017). "Twin 515-foot Columns Completed as City Celebrates "Topping Off" of New Gerald Desmond Bridge". Long Beach Post. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- Ortega, Norma (October 19–20, 2016). "Supplemental funds allocation for Gerald Desmond Bridge design-build project resolution FA-16-07" (PDF). Letter to Chair and Commissioners, California Transportation Commission. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Stocking, Angus (June 18, 2014), "Innovative System Ensures Vertical Alignment of Gerald Desmond Bridge", Point of Beginning, Troy, Michigan: BNP Media

- Gish, Judy (December 2010). "New Gerald Desmond: a Bridge to California's Economic Future". InsideSeven. Caltrans District 7. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- 2015 Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California (Report). California Department of Transportation. 2016. p. 143.

Mark Bixby Memorial Bicycle Pedestrian Path

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - California State Assembly. "Assembly Concurrent Resolution No. 100". Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California (Resolution). State of California. Ch. 109."Assembly Concurrent Resolution No. 100". 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Barboza, Tony (March 16, 2011). "Long Beach plane crash claims community leaders, member of founding Bixby family [BLOG]". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- "New Bridge at a Glance". New Gerald Desmond Bridge. 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

Note 1: WEST APPROACH: The 2,800-ft. west approach will be on Terminal Island.

Note 7: TOWERS: At 515 feet tall, the bridges two towers will be the second-tallest of any cable-stayed bridge in the U.S. The steel-reinforced concrete towers will be supported by massive foundations. The tower design – unique to this bridge – transitions from an octagon shape at the base to diamond shape at the top.

Note 8: CABLE-STAYED BRIDGE: The new bridge is a cable-stayed design, in which cables directly connect the towers to the road deck (unlike a traditional suspension bridge, which uses cables draped over towers). The entire length of the bridge – main span and approaches – will be 8,800 feet.

Note 9: SPAN: The main span and back spans of the bridge will be 2,000 feet long and 205 feet above the water. It will be the highest deck of any cable-stayed bridge in the U.S.

Note 10: EAST APPROACH: The 3,600-ft. east approach will connect the bridge to both the Long Beach (710) Freeway and east Ocean Boulevard toward downtown Long Beach. - Cho, Aileen (June 12, 2019). "Gerald Desmond Bridge Nears Completion". Engineering News-Record. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- Zummallen, Ryan (September 29, 2010). "Gerald Desmond Bridge Construction Approved By Long Beach City Council". Long Beach Post. Archived from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- "Caltrans, Port Select Bidders for Bridge Project" (Press release). Port of Long Beach. March 4, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- "Caltrans, Port Receive Bridge Replacement Proposals" (Press release). Port of Long Beach. March 2, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- "Commission OKs Desmond Bridge Recommendation" (Press release). Port of Long Beach. May 16, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- "Harbor Commission Awards Bridge Design-Build Contract" (Press release). Port of Long Beach. July 23, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- "Port of Long Beach approves bridge replacement". Bridge Design & Engineering. August 10, 2010. Retrieved August 16, 2010.

- Gish, Judy. "Building Bridges, Raising Economies". InsideSeven. Caltrans District 7. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- "Strategic Oversight Agreement for Gerald Desmond Bridge Replacement" (PDF). Caltrans. February 21, 2008. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

This project consists of replacement of the aging Gerald Desmond Drive. The project location is in the Back Channel area of the Port of Long Beach, centered along Ocean Blvd. From the intersection of the Terminal Island Freeway (SR-47) at the western end to its terminus at the westerly end of the bridge over the Los Angeles River. The total project cost is estimated to be $721,400,000 subject to escalation from a base November 2005 dollar. Project cost will be revised at environmental certification scheduled for third quarter of 2008. Caltrans fact sheet for project shows construction costs of $800,500,000 with $65,000,000 support costs. - Robes Meeks, Karen (October 5, 2013). "Maze of oil wells, utility lines complicates Gerald Desmond Bridge project". Long Beach Press Telegram. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- Edwards, Andrew (July 14, 2015). "Price tag to replace Gerald Desmond Bridge in Long Beach jumps by more than $200 million". Long Beach Press-Telegram.

- Robes Meeks, Karen (June 24, 2014). "Design issues delay Gerald Desmond Bridge replacement project". Long Beach Press Telegram. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- Edwards, Andrew (April 22, 2015). "Workers laying foundation for the new Gerald Desmond Bridge in Long Beach". Long Beach Press Telegram. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- Edwards, Andrew (April 18, 2016). "How high-tech scaffolding is helping build Gerald Desmond Bridge in Long Beach". Long Beach Press Telegram. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- Robes Meeks, Karen (October 1, 2014). "Gerald Desmond Bridge project milestone marked by city, Port of Long Beach officials". Long Beach Press Telegram. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- Aragon, Greg (August 3, 2016). "Construction on $1.2- billion Gerald Desmond Bridge Project Passes Halfway Point". Engineering News-Review [blog]. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- Grobaty, Tim (February 23, 2011). "Ready for action". Long Beach Press-Telegram. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gerald Desmond Bridge. |

External links

- Gerald Desmond Bridge at Structurae

- Gerald Desmond Bridge (2016) at Structurae

- "Gerald Desmond Bridge". Bridgehunter. 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- "Ocean Blvd over Water St, Channel, UP RR". Uglybridges. 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- New GD Bridge project page

- Port Of Long Beach GD bridge replacement page

- GD bridge replacement project at shimmick.com (contractor)