Gascony

Gascony (/ˈɡæskəni/; French: Gascogne [ɡaskɔɲ]; Gascon: Gasconha [ɡasˈkuɲɔ]; Basque: Gaskoinia) is a province of southwestern France that was part of the "Province of Guyenne and Gascony" prior to the French Revolution. The region is vaguely defined, and the distinction between Guyenne and Gascony is unclear; by some they are seen to overlap, while others consider Gascony a part of Guyenne. Most definitions put Gascony east and south of Bordeaux.

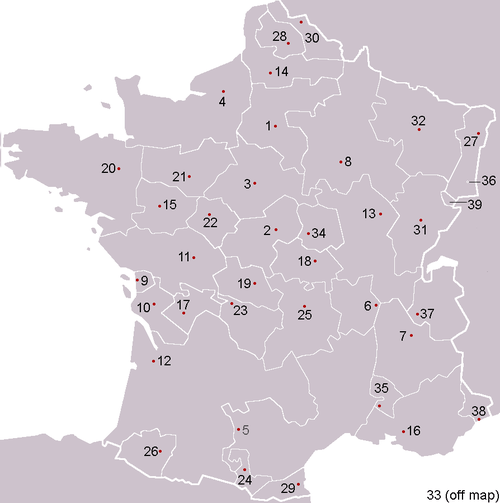

It is currently divided between the region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine (departments of Landes, Pyrénées-Atlantiques, southwestern Gironde, and southern Lot-et-Garonne) and the region of Occitanie (departments of Gers, Hautes-Pyrénées, southwestern Tarn-et-Garonne, and western Haute-Garonne).

Gascony was historically inhabited by Basque-related people who appear to have spoken a language similar to Basque. The name Gascony comes from the same root as the word Basque (see Wasconia below). From medieval times until today, the Gascon language has been spoken, although it is classified as a regional variant of the Occitan language.

Gascony is the land of d'Artagnan, who inspired Alexandre Dumas's character d'Artagnan in The Three Musketeers, as well as the land of Cyrano de Bergerac, who inspired the play of the same name by Edmond Rostand. It is also home to Henry III of Navarre, who later became king of France as Henry IV.

History

Aquitania

In pre-Roman times, the inhabitants of Gascony were the Aquitanians (Latin: Aquitani), who spoke a non-Indo-European language related to modern Basque.

The Aquitanians inhabited a territory limited to the north and east by the Garonne River, to the south by the Pyrenees mountain range, and to the west by the Atlantic Ocean. The Romans called this territory Aquitania, either from the Latin word aqua (meaning "water"), in reference to the many rivers flowing from the Pyrenees through the area, or from the name of the Aquitanian Ausci tribe, in which case Aquitania would mean "land of the Ausci".

In the 50s BC, Aquitania was conquered by lieutenants of Julius Caesar and became part of the Roman Empire.

Later, in 27 BC, during the reign of Emperor Augustus, the province of Gallia Aquitania was created. Gallia Aquitania was far larger than the original Aquitania, as it extended north of the Garonne River, in fact all the way north to the Loire River, thus including the Celtic Gauls that inhabited the regions between the Garonne and the Loire rivers.

Novempopulana

In 297, as Emperor Diocletian reformed the administrative structures of the Roman Empire, Aquitania was split into three provinces. The territory south of the Garonne River, corresponding to the original Aquitania, was made a province called Novempopulania (that is, "land of the nine tribes"), while the part of Gallia Aquitania north of the Garonne became the province of Aquitanica I and the province of Aquitanica II. The territory of Novempopulania corresponded quite well to what we call now Gascony.

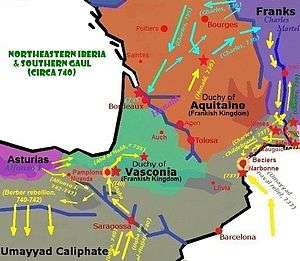

The Aquitania Novempopulana or Novempopulania suffered like the rest of the Western Roman Empire from the invasions of Germanic tribes, most notably the Vandals in 407–409. In 416–418, Novempopulania was delivered to the Visigoths as their federate settlement lands and became part of the Visigoth kingdom of Toulouse, while other than the region of the Garonne river their actual grip on the area may have been rather loose.

The Visigoths were defeated by the Franks in 507, and fled into Spain and Septimania. Novempopulania then became part of the Frankish Kingdom like the rest of southern France. However, Novempopulania was far away from the home base of the Franks in northern France, and was only very loosely controlled by the Franks. During all the troubled and historically obscure period, starting from early 5th-century accounts, the bagaudae are often cited, social uprisings against tax exaction and feudalization, largely associated to Vasconic unrest.

Wasconia

Old historical literature sometimes claims the Basques took control of the whole of Novempopulania in the Early Middle Ages, founding its claims on the testimony of Gregory of Tours, on the etymological link between the words "Basque" and "Gascon" – both derived from "Vascones" or "Wasconia", the latter being used to name the whole of Novempopulania.

Modern historians reject this hypothesis, which is sustained by no archeological evidence. For Juan José Larrea, and Pierre Bonnassie, "a Vascon expansionism in Aquitany is not proved and is not necessary to understand the historical evolution of this region".[1] This Basque-related culture and race is, whatever the origin, attested in (mainly Carolingian) Medieval documents, while their exact boundaries remain unclear ("Wascones, qui trans Garonnam et circa Pirineum montem habitant" -- "Wascones, who live across the Garonne and around the Pyrenees mountains", as stated in the Royal Frankish Annals, for one).[2]

The word Vasconia evolved into Wasconia, and then into Gasconia (w often evolved into g under the influence of Romance languages; cf. warranty and guarantee, warden and guardian, wile and guile, William and Guillaume). The gradual abandonment of the Basque-related Aquitanian language in favor of a local Vulgar Latin was not reversed. The replacing local Vulgar Latin evolved into Gascon. It was heavily influenced by the original Aquitanian language (for example, Latin f became h; cf. Latin fortia, French force, Spanish fuerza, Occitan fòrça, but Gascon hòrça). Interestingly, the Basques from the French side of the Basque Country traditionally call anyone who does not speak Basque a "Gascon".

Meanwhile, Viking raiders conquered several Gascon towns, among them Bayonne in 842–844. Their attacks in Gascony may have helped the political disintegration of the Duchy until their defeat against William II Sánchez of Gascony in 982. In turn, the weakened ethnic polity known as Duchy of Wasconia/Wascones, unable to get round the general spread of feudalization, gave way to a myriad of counties founded by Gascon lords.

Angevin Empire

His 1152 marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine allowed the future Henry II to gain control of his new wife's possessions of Aquitaine and Gascony. This addition to his already plentiful holdings made Henry the most powerful vassal in France.[3]

In 1248, Simon de Montfort was appointed Governor in the unsettled Duchy of Gascony. Bitter complaints were excited by de Montfort's rigour in suppressing the excesses of both the seigneurs of the nobility and the contending factions in the great communes. Henry III yielded to the outcry and instituted a formal inquiry into Simon's administration. Simon was formally acquitted of the charges, but in August 1252 he was nevertheless dismissed. Henry then himself went to Gascony, pursuing a policy of conciliation; he arranged the marriage between Edward, his 14-year-old son, and Eleanor of Castile, daughter of Alfonso X. Alfonso renounced all claims to Gascony and assisted the Plantagenets against rebels such as Gaston de Bearn, who had taken control of the Pyrenees.[4]

In December 1259, Louis IX of France ceded to Henry land north and east of Gascony.[5] In return, Henry renounced his claim to many of the territories that had been lost by King John.

In May 1286, King Edward I paid homage before the new king, Philip IV of France, for the lands in Gascony. However, in May 1295, Philip "confiscated" the lands. Between 1295 and 1298, Edward sent three expeditionary forces to recover Gascony, but Philip was able to retain most of the territory until the Treaty of Paris in 1303.[6]

In 1324 when Edward II of England, in his capacity as Duke of Aquitaine, failed to pay homage to the French king after a dispute, Charles IV declared the duchy forfeit at the end of June 1324, and military action by the French followed. Edward sent his wife Isabella, who was sister to the French king, to negotiate a settlement. The Queen departed for France on 9 March 1325, and in September was joined by her son, the heir to the throne, Prince Edward (later Edward III of England). Isabella's negotiations were successful, and it was agreed that the young Prince Edward would perform homage in the king's place, which he did on 24 September and so the duchy was returned to the English crown.[7]

When France's Charles IV died in 1328 leaving only daughters, his nearest male relative was Edward III of England, the son of Isabella, the sister of the dead king; but the question arose whether she could legally transmit the inheritance of the throne of France to her son even though she herself, as a woman, could not inherit the throne. The assemblies of the French barons and prelates and the University of Paris decided that males who derive their right to inheritance through their mother should be excluded. Thus the nearest heir through male ancestry was Charles IV's first cousin, Philip, Count of Valois, and it was decided that he should be crowned Philip VI of France. Philip believed that Edward III was in breach of his obligations as vassal, so in May 1337 he met with his Great Council in Paris. It was agreed that Gascony should be taken back into Philip's hands, thus precipitating the Hundred Years War between England and France.[8][9] At the end of the Hundred Years' War, after Gascony had changed hands several times, the English were finally defeated at the Battle of Castillon on 17 July 1453; Gascony remained French from then on.[10]

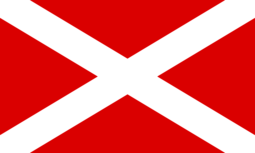

Flags

The Saltire, lo Sautèr

| |

| Names | Union Gascona, Flag of Gascony |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 3:5 |

| Design | 1188? |

| Designed by | unknown |

The Gascony does not have any institutional unity since the 11th century, hence several flag versions are currently used on the territory.

The Saltire, sometimes called "Union Gascona" (Gascon Union) is a white Saint-Andrew's cross on a red background. Some say that it was originally given by Pope Clement III at the time of the Third Crusade but there has been no evidence of that assumption yet.

It is often said that the text of the chronicler Roger of Howden mentioned that Pope Clement III gave crosses to the kings of France and England (Richard I of England as well duke of Aquitania and Gascony) during the Gisors conference in 1188 and that these kings then assigned flags, with the cross on it, to their respective nations. The following text ("The French flags" on the website Heraldica, accessed 04-22-2010) is about this event: The kings of France and England were in a peace conference in a field between Gisors and Trie, in January 1188, when the archbishop of Tyre arrived with the news of the conquest of Jerusalem by Saladdin, and an urgent plea for a new crusade. The event is told by the contemporary chronicler Roger de Hoveden (R. de Houedene, Chronica, ed. William Stubbs, vol. 2, London, 1869, p. 335). At this conference came the archbishop of Tyre, who [...] moved their hearts to taking the cross. And those who were enemies before, by his predication and God’s help, became friends that day, and received the cross from his hand ; and in that moment the sign of the cross appeared above them in the sky. On seeing that miracle, many rushed in droves to take the cross. And said kings, when taking the cross, chose a visible sign for themselves and their people to identify their nation. The king of France and his people took red crosses ; the king of England with his people took white crosses ; and Philip count of Flanders with his people took green crosses ; and thus everyone returned home to provide for the needs of his journey. [… ad cognoscendam gentem suam signum evidens sibi et suis providerunt, ... et sic unusquisque ...]

The original text of Howden stops here. What comes next is an addition from F. Velde: "It is often said that the system was extended to other regions or nations : Brittany’s cross was black, Lorraine green, Italy and Sweden yellow, Burgundy a red Saint Andrew’s, Gascony a white Saint Andrew’s."

Thus we cannot confirm that the gascon saltire comes from the Crusades or even the Middle Ages. At least was it known at the time when F. Velde wrote this article. As Saint Andrew is the patron of Bordeaux that could be a hint for its origin.

In the tome 14 of the Grande Encyclopédie, published in France between 1886 and 1902 by Henri Lamirault, one can read that

" aux temps difficiles de la guerre de Cent ans et des luttes terribles entre les Armagnacs représentant le parti national (croix blanche) et les Bourguignons alliés des Anglais (croix rouge et croix rouge de Saint-André), le drapeau des Anglais victorieux finit par réunir, en 1422, sous Henri VI, sur son champ les croix blanche et rouge de France et d'Angleterre, les croix de Saint-André, blanche et rouge de Guyenne et de Bourgogne. "[11]

(During the hard times of the Hundred Years' War and the terrible struggles between the Armagnacs, representing the national party (white cross) and the Burgundians, allied to the English (red cross and red Saint-Andrews' cross), the flag of the victorious English ends up gathering, in 1422, under Henri VI, on its field the white and red crosses of France and England, the white and red Saint-Andrew's crosses of Guyenne and Burgundy.)

On the website Gasconha.com a message from M. Fourment (12-15-2006) returns to the website svowebmaster.free.fr on which would be written that the Saltire was declared "official flag of Gascony" on 13 January in 1903, but without any other precision, nor source (perhaps was it in the context of the Félibrige that was then developing).

The red and white colors are statistically dominants in the heraldry of the gascon countries. This red and white flag, or Saltire, lo(u) Sautèr, is considered as being the flag of the Gascon people.

Therefore this gascon saltire could have picked up some ancient traditions. Even if it would only be dated from the end of the 19th century of the beginning of the 20th, it follows the rules of vexillology (simplicity, distant readability). It corresponds to the color and the pattern of the talenquères in many bullrings in Gascony.

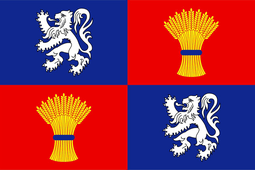

The Quarterly, l'Esquarterat

| |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

|---|---|

| Design | XXe century |

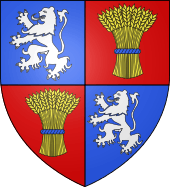

However, another flag is used: the Quarterly. It corresponds to the arms of the ancient province of Gascony put in a banner.

This province was smaller than the current Gascony (also called "cultural and linguistic Gascony), it included neither the Béarn nor the gascon part of the Guyenne, but it included the basque provinces of the Labourd and the Soule.

Geography

Gascony is limited by the Atlantic Ocean (western limit) and the Pyrenees mountains (southern limit); as the area of Gascon language, it extends to the Garonne (North), and close to the Ariège (river) (East) from the Pyrenees to the confluence of the Garonne with the Ariège. The other most important river is Adour, along with its tributaries Gave de Pau and Gave d'Oloron.

The most important towns are:

- Auch, the historical capital

- Bayonne, with both Basque and Gascon identity

- Bordeaux, crossed by the Garonne

- Dax

- Lourdes

- Luchon

- Mont-de-Marsan

- Pau

- Tarbes

Bayonne, Dax and Tarbes are crossed by the Adour. Pau and Lourdes are crossed by the Gave de Pau. Mont-de-Marsan also belongs to the drainage basin of the Adour. The Gers (river), a tributary of the Garonne, flows through Auch.

Economy

The main economic activities are:

- forestry

- agriculture

- stock raising

- fruit and vegetables

- fishing

- wine and brandy

- tourism

- gas and oil

- chemicals

- aerospace industry

- wood products and packaging

- food processing

- metallurgy

- renewable energy

- Catholic pilgrimages in Lourdes

References

- Juan José Larrea, Pierre Bonnassie: La Navarre du IVe au XIIe siècle: peuplement et société, page 123-129, De Boeck Université, 1998

- "The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718–1050". THE LIBRARY OF IBERIAN RESOURCES ONLINE. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- Harvey, The Plantagenets, p.47

- p276 Chronicle of Britain ISBN 1-872031-35-8

- p280 Chronicle of Britain ISBN 1-872031-35-8

- p297 Chronicle of Britain ISBN 1-872031-35-8

- Chris Given-Wilson, ed. (2010). Fourteenth Century England VI: 6. London: Boydell Press. pp. 34–36. ISBN 978-1-8438-3530-1.

- Previte-Orton, C.W (1978). The shorter Cambridge Medieval History 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 872. ISBN 978-0-521-20963-2.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1991). The Hundred Years War I: Trial by Battle. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-8122-1655-4.

- Wagner, John A (2006). Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War. Westport CT: Greenwood Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-313-32736-0.

- https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k24649b/f1071.item

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gascogne. |

| Look up Gascony in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |