Furusiyya

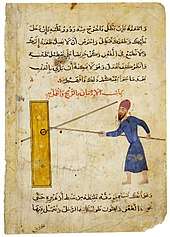

Furūsiyya (فروسية; also transliterated as furūsīyah) is the historical Arabic term for equestrian martial exercise.

Furūsiyya as a science is especially concerned with the martial arts and equestrianism of the Golden Age of Islam and the Mamluk period (roughly 10th to 15th centuries), reaching its peak in Mamluk Egypt during the 14th century.

Its main branches concerned horsemanship (including aspects of both hippology and equestrianism), horse archery and use of the lance, with the addition of swordsmanship as fourth branch in the 14th century.

The term is a derivation of faras (فرس) "horse", and in Modern Standard Arabic means "equestrianism" in general. The term for "horseman" or "cavalier" ("knight") is fāris, which is also the origin of the Spanish rank of alférez.[1] It is also a possible origin of the still common Spanish surname Álvarez. The Perso-Arabic term for "Furūsiyya literature" is faras-nāma or asb-nāma.[2]

History

Furusiyya literature, the Arabic literary tradition of veterinary medicine (hippiatry) and horsemanship, much like in the case of human medicine, was adopted wholesale from Byzantine Greek sources in the 9th to 10th centuries. In the case of furusiyya, the immediate source is the Byzantine compilation on veterinary medicine known as Hippiatrica (5th or 6th century); the very word for "horse doctor" in Arabic, bayṭar, is a loan of Greek ἱππιατρός hippiatros.[3]

The first known such treatise in Arabic is due to Ibn Akhī Ḥizām (ابن أخي حزام), an Abbasid-era commander and stable master to caliph Al-Muʿtadid (r. 892–902), author of Kitāb al-Furūsiyya wa 'l-Bayṭara ("Book of Horsemanship and Hippiatry").[4] Ibn al-Nadim in the late 10th century records the availability in Baghdad of several treatises on horses and veterinary medicine attributed to Greek authors.[5]

The discipline reaches its peak in Mamluk Egypt during the 14th century. In a narrow sense of the term, furūsiyya literature comprises works by professional military writers with a Mamluk background or close ties to the Mamluk establishment. These treatises often quote pre-Mamluk works on military strategy. Some of the works were versified for didactic purposes. The best known versified treatise is the one by Taybugha al-Baklamishi al-Yunani ("the Greek"), who in c. 1368 wrote the poem al-tullab fi ma'rifat ramy al-nushshab.[6] By this time, the discipline of furusiyya becomes increasingly detached from its origins in Byzantine veterinary medicine and more focussed on military arts.

The three basic categories of furūsiyya are horsemanship (including veterinary aspects of proper care for the horse, the proper riding techniques), archery, and charging with the lance. Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya adds swordsmanship as a fourth discipline in his treatise Al-Furūsiyya ( 1350).[7]

Persian faras-nāma which can be dated with confidence are extant only from about the mid-14th century, but the tradition survives longer in Persia, throughout the Safavid era. One treatise by ʿAbd-Allāh Ṣafī, known as the Bahmanī faras-nāma (written in 1407/8) is said to preserve a chapter from an otherwise lost 12th-century (Ghaznavid-era) text.[2] There is a candidate for another treatise of this age, extant in a single manuscript: the treatise attributed to one Moḥammad b. Moḥammad b. Zangī, also known as Qayyem Nehāvandī, has been tentatively dated as originating in the 12th century.[2] Some of the Persian treatises are translations from the Arabic. One short work, attributed to Aristotle, is a Persian translation from the Arabic.[8] There are supposedly also treatises translated into Persian from Hindustani or Sanskrit. These include the Faras-nāma-ye hāšemī by Zayn-al-ʿĀbedīn Ḥosaynī Hašemī (written 1520), and the Toḥfat al-ṣadr by Ṣadr-al-Dīn Moḥammad Khan b. Zebardast Khan (written 1722/3).[2] Texts thought to have been originally written in Persian include the Asb-nāma by Moḥammad b. Moḥammad Wāseʿī (written 1365/6; Tehran, Ketāb-ḵāna-ye Malek MS no. 5754). A partial listing of known Persian faras-nāma literature was published by Gordfarāmarzī (1987).[9]

List of Furusiyyah treatises

The following is a list of known Furusiyyah treatises (after al-Sarraf 2004, al-Nashīrī 2007).[10]

Some of the early treatises (9th to 10th centuries) are not extant and only known from references by later authors: Al-Asma'i, Kitāb al-khayl (خيل "horse"), Ibn Abi al-Dunya (d. 894 / AH 281) Al-sabq wa al-ramī, Al-Ṭabarānī (d. 971 / AH 360) Faḍl al-ramī, Al-Qarrāb (d. 1038 / AH 429), Faḍā'il al-ramī.

| Author | Date | Title | Manuscripts / Editions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ibn Akhī Hizām (Muḥammad ibn Yaʿqūb ibn Ghālib ibn ʿAlī al-Khuttalī) | fl. c. 900[4] | "Kitāb al-Furūsiyya wa-al-Bayṭarah" (or "Kitāb al-Furūsiyya wa-Shiyāt al-Khayl") | Istanbul, Bayezit State Library, Veliyüddin Efendi MS 3174; British Library MS Add. 23416 (14th century);[11] Istanbul, Fatih Mosque Library MS 3513 (added title "Al-Kamāl fī al-Furūsiyya...");

ed. Heide (2008).[12] | |

| Al-Tarsusi (Marḍī ibn ʿAlī al-Ṭarsūsī) | died 1193 / AH 589 | "Tabṣirat arbāb al-albāb fī kayfīyat al-najāt fī al-ḥurūb min al-anwā' wa-nashr aʿlām al-aʿlām fī al-ʿudad wa-al-ālāt al-muʿayyanah ʿalá liqā' al-aʿdā'" | Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Huntington 264 | |

| Abū Aḥmad (Abū Muḥammad Aḥmad ibn ‘Atīq al-Azdī) | 1223 / AH 620 | "Kitāb al-furūsiyya wa-l-bayṭarah" (an abbreviated version of Ibn Akhī Ḥizām's treatise) | British Library Or 1523[13] | |

| Al-Zahirī (Badr al-Dīn Baktūt al-Rammāḥ al-Khāzindārī al-Zahirī) | 13th century | "Kitāb fī ʿIlm al-Furūsiyya wa-Laʿb al-Rumḥ wa-al-Birjās wa-ʿIlāj al-Khayl" (or "ʿIlm al-Furūsiyya wa-Siyāsat al-Khayl", "Al-Furūsiyya bi-rasm al-Jihād wa-mā aʿadda Allāh li 'l-Mujāhidīn min al-ʿIbād") | Bibliothèque Nationale MS 2830 (fols. 2v.–72r.);

ed. al-Mihrajān al-Waṭanī lil-Turāth wa-al-Thaqāfah, Riyadh (1986); ed. Muḥammad ibn Lājīn Rammāḥ, Silsilat Kutub al-turāth 6, Damascus, Dār Kinān (1995). | |

| Al-Aḥdab (Najm al-Dīn Ḥasan al-Rammāḥ) | died 1295 / AH 695 | "Al-Furūsiyya wa-al-manāṣib al-ḥarbiyya" (The book of military horsemanship and ingenious war devices) | ed. ʿĪd Ḍayf ʿAbbādī, Silsilat Kutub al-turāth, Baghdad (1984). | |

| Al-Ḥamwī (Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm Ibn Jamāʿah al-Ḥamwī) | died 1332 / AH 733 | "Mustanad al-ajnād fī ālāt al-jihād" | ||

| Ibn al-Mundhir (Abū Bakr al-Bayṭar ibn Badr al-Dīn al-Nāsirī) | died 1340/1 | "Kāshif al-Wayl fī Maʿrifat Amrāḍ al-Khayl" (or "Kāmil al-ṣināʿatayn fī al-Bayṭarah wa-al-Zardaqah") | Bibliothèque Nationale MS 2813 | |

| Al-Aqsarā'ī (Muḥammad ibn ʿIsá ibn Ismāʿīl al-Hanafī al-Aqsarā'ī) | died 1348 | "Nihāyat al-Sūl wa-al-Umniyya fī Taʿlīm Aʿmāl al-Furūsiyya" | British Library MS Add. 18866 (dated 1371 / AH 773);[14] Chester Beatty Library MS Ar 5655 (dated 1366 / AH 788). | |

| Al-Nāṣirī (Muḥammad Ibn Manglī al-Nāṣirī) | died after 1376 | "Al-Adillah al-Rasmiyya fī al-Taʿābī al-Harbiyya" | Istanbul, Ayasofya Library MS 2857 | |

| Al-Nāṣirī (Muḥammad Ibn Manglī al-Nāṣirī) | died after 1376 | "Al-Tadbīrāt al-Sulṭāniyya fī Siyāsat al-Sināʿah al-Harbiyya" | British Library MS Or. 3734 | |

| Al-Nāṣirī (Muḥammad Ibn Manglī al-Nāṣirī) | died after 1376 | "Uns al-Malā bi-Waḥsh al-Falā" | Bibliothèque Nationale MS 2832/1 | |

| Aṭājuq (Alṭanbughā al-Husāmī al-Nāṣirī) | 1419 / AH 822 | "Nuzhat al-Nufūs fī Laʿb al-Dabbūs" | Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyya MS 21 furūsiyya Taymūr[15] | |

| Sulaymānah (Yūsuf ibn Aḥmad) | written before 1427 / AH 830 | "Faraj al-Makrūb fī aḥkām al-ḥurūb wa muʻānātihā wa-mudaratiha wa-lawazimiha wa-ma yasu'u bi-amrihā" | ||

| Muhammad ibn Yaʿqūb ibn aḫī Ḫozām | 1470 / 1471 | "Kitāb al-makhzūn jāmiʻ al-funūn" | Bibliothèque Nationale MS Ar 2824[16] | |

| "Al-ʿAdīm al-Mithl al-Rafīʿ al-Qadr" | Istanbul, Topkapı Sarayı Library MS Revan 1933 | |||

| pseudo-Al-Aḥdab; Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad Abū al-Maʿālī al-Kūfī | 17th century | "Kitāb al-Furūsiyya" (added title) | Bibliothèque Nationale MS 2829[17] | |

| Al-Asadī (Abū al-Rūḥ ʿIsá ibn Hassān al-Asadī al-Baghdādī) | "Al-Jamharah fī ʿUlūm al-Bayzarah" | British Library MS Add. 23417; Madrid, Escorial Library MS Ar. 903 | ||

| ʿUmar ibn Raslān al-Bulqīnī | "Qaṭr al-Sayl fī Amr al-Khayl" | Istanbul, Süleymaniye Library MS Şehid Alī Pasha 1549 | ||

| Sharaf al-Dīn ʿAbd al-Mu'min ibn Khalaf al-Dimyāṭī | "Faḍl al-Khayl" | Bibliothèque Nationale MS 2816 | ||

| Abū Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn ʿAbd Allāh Ibn Maymūn | "Kitāb al-Ifādah wa-al-Tabṣīr li-Kull Rāmin Mubtadi' aw Māhir Naḥrīr bi-al-Sahm al-Tawīl wa-al-Qaṣīr" | Istanbul, Köprülü Mehmet Pasha Library MS 1213 | ||

| ʿAlā'al-Dīn ʿAlī ibn Abī al-Qāsim al-Naqīb al-Akhmīmī | "Hall al-Ishkāl fī al-Ramy bi-al-Nibāl" | Bibliothèque Nationale MS 6259 | ||

| ʿAlā'al-Dīn ʿAlī ibn Abī al-Qāsim al-Naqīb al-Akhmīmī | "Naqāwat al-Muntaqá fī Nāfiʿāt al-Liqā" | British Library MS Add. 7513/2 | ||

| Rukn al-Dīn Jamshīd al-Khwārazmī | untitled | British Library MS Or. 3631/3 | ||

| "Kitāb fī Laʿb al-Dabbūs wa-al-Sirāʿ ʿalá al-Khayl" | Bibliothèque Nationale MS Ar. 6604/2 | |||

| "Kitāb al-Hiyal fī al-Hurūb wa-Fatḥ al-Madā'in wa-Hifz al-Durūb" | British Library MS Add. 14055 | |||

| "Kitāb al-Makhzūn Jāmiʿ al-Funūn" / "Kitāb al-Makhzūn li-Arbāb al-Funūn" | Bibliothèque Nationale MS 2824 and MS 2826 | |||

| Husām al-Dīn Lājīn ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Dhahabī al-Husāmī al-Tarābulṣī al-Rammāḥ | "Kitāb ʿUmdat al-Mujāhidīn fī Tartīb al-Mayādīn" | Bibliothèque Nationale MS Ar. 6604/1 | ||

| "Al-Maqāmah al-Salāḥiyya fī al-Khayl wa-al-Bayṭarah wa-al-Furūsiyya" | Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyya MS 81 furūsiyya Taymūr | |||

| Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Sakhāwī | "Al-Qawl al-Tāmm fī (Faḍl) al-Ramy bi-al-Sihām" | Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyya MS 2m funūn ḥarbiyya | ||

| "Sharḥ al-Maqāmah al-Salāḥiyya fī al-Khayl" | Bibliothèque Nationale MS Ar. 2817 | |||

| al-Hasan ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAysūn al-Hanafī al-Sinjārī | "Hidāyat al-Rāmī ilá al-Aghrāḍ wa-al-Marāmī" | Istanbul, Topkapı Sarayı Library MS Ahmet III 2305 | ||

| Nāṣir al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī al-Qāzānī al-Sughayyir | "Al-Mukhtaṣar al-Muḥarrar" | Istanbul, Topkapı Sarayı Library MS Ahmet III 2620 | ||

| Nāṣir al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī al-Qāzānī al-Sughayyir | "Al-Hidāyah fī ʿIlm al-Rimāyah" | Bodleian Library MS Huntington 548 | ||

| Nāṣir al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī al-Qāzānī al-Sughayyir | "Sharḥ al-Qaṣīdah al-Lāmiyya lil-Ustādh Sāliḥ al-Shaghūrī" | Bibliothèque Nationale MS Ar 6604/3 | ||

| Jalāl al-Dīn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Abī Bakr al-Suyūṭī | "Ghars al-Anshāb fī al-Ramy bi-al-Nushshāb" | British Library MS Or. 12830 | ||

| Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Aḥmad al-Tabarī | untitled fragment | British Library MS Or. 9265/1 | ||

| Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Aḥmad al-Tabarī | "Kitāb al-Wāḍiḥ (fī ʿIlm al-Ramy)" | British Library MS Or. 9454 | ||

| Taybughā al-Ashrafī al-Baklamīshī al-Yunānī | "Kitāb al-Ramy wa-al-Rukūb" (added title) | Bibliothèque Nationale MS 6160 | ||

| Husayn ibn ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Yūnīnī | "Al-Nihāyah fī ʿIlm al-Rimāyah" | Istanbul, Ayasofya Library MS 2952 | ||

| Abū al-Naṣr al-Qāsim ibn ʿAlī ibn Husayn al-Hāshimī al-Zaynabī | "Al-Qawānīn al-Sulṭāniyya fī al-Sayd" | Istanbul, Fatih Mosque Library MS 3508 | ||

Fāris

The term furūsiyya, much like its parallel chivalry in the West, also appears to have developed a wider meaning of "martial ethos". Arabic furusiyya and European chivalry has both influenced each other as a means of a warrior code for the knights of both cultures.[18][19]

The term fāris (فارس) for "horseman" consequently adopted qualities comparable to the Western knight or chevalier ("cavalier"). This could include free men (such as Usama ibn Munqidh), or unfree professional warriors, like ghulams and mamluks). The Mamluk-era soldier was trained in the use of various weapons such as the sword, spear, lance, javelin, club, bow and arrows and tabarzin or axe (hence Mamluk bodyguards known as tabardariyya), as well as wrestling.[20]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Furusiyya. |

- Hippiatrica

- Shalihotra Samhita

- Bem cavalgar

- History of veterinary medicine

- Horses in the Middle Ages

- Horses in warfare

- Aswaran

- Futuwwa

References

- Simon Barton, The Aristocracy in Twelfth-century León and Castile, Cambridge (1997), 142–44.

- Īraj Afšār, Encyclopedia Iranica s.v. "FARAS-NĀMA" (1999).

- Anne McCabe, A Byzantine Encyclopaedia of Horse Medicine: The Sources, Compilation, and Transmission of the Hippiatrica (2007), p. 184, citing: A. I. Sabra, "The Appropriation and Subsequent Naturalization of Greek Science in Medieval Islam: A Preliminary Statement", History of Science 25 (1987), 223–243,; M. Plessner in: Encyclopedia of Islam s.v. "bayṭar" (1960);

- Daniel Coetzee, Lee W. Eysturlid, Philosophers of War: The Evolution of History's Greatest Military Thinkers (2013), p. 59. "Ibn Akhī Hizām" ("the son of the brother of Hizam", viz. a nephew of Hizam Ibn Ghalib, Abbasid commander in Khurasan, fl. 840).

- B. Dodge (tr.), The Fihrist of Al-Nadim (1970), 738f. (cited after McCabe (2007:184).

- ed. and trans. Latham and Paterson, London 1970

- "Arab epic heroes and horses". Halle an der Saale: 29. Deutscher Orientalistentag. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

Furusiyya covers four disciplines: the tactics of attack and withdrawal (al-karr wa-l-farr); archery; jousts with spears; duels with swords. [...] Only the Muslim conquerors and the knights of the faith have fully mastered these four arts.

- ed. Ḥasan Tājbaḵš, Tārīḵ-e dāmpezeškī wa pezeškī-e Īrān I, Tehran (1993), 414–428.

- ʿĀ. Solṭānī Gordfarāmarzī, ed., Do faras-nāma-ye manṯūr wa manẓūm, Tehran (1987).

- Ibn Qayyim al-Jawzīyah, Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr (2007), al-Nashīrī, Zāʼid ibn Aḥmad (ed.), Al-furūsiyya al-Muḥammadīyah, Dār ʻĀlam al-Fawāʼid lil-Nashr wa-al-Tawzīʻ, pp. 7–9

- Qatar Digital Library: Add MS 23416

- Martin Heide (trans.), Das Buch der Hippiatrie, Kitāb al-Bayṭara, Veröffentlichungen der Orientalischen Kommission 51.1-2, Harrassowitz (2008).

- Qatar Digital Library: Or 1523

- A Mamluk Manuscri(bl.uk), Qatar Digital Library

- Mamlūk Studies Review 8 (2004), 176.

- Bibliothèque Nationale MS Ar 2824

- M. Reinaud, "De l'art militaire chez les Arabes au Moyen-Age ", Journal asiatique, septembre 1848, p. 193-237

- Hermes, Nizar (December 4, 2007). "King Arthur in the Lands of the Saracen" (PDF). Nebula.

- Burton, Richard Francis (1884). Read, Charles Anderson; O'Connor, Thomas Power (eds.). The cabinet of Irish literature: selections from the works of the chief poets, orators, and prose writers of Ireland, with biographical sketches and literary notices, Vol. IV. London; New York: Blackie & Son; Samuel L. Hall. p. 94.

Were it not evident that the spiritualising of sexuality by imagination is universal among the highest orders of mankind, I should attribute the origin of love to the influence of the Arabs' poetry and chivalry upon European ideas rather than to medieval Christianity.

- Nicolle, David (1994). Saracen Faris AD 1050–1250 (Warrior). Osprey Publishing. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-1-85532-453-4.

Sources

- Ayalon, David (1961). Notes on the Furusiyya Exercises and Games in the Mamluk Sultanate, Scripta Hierosolymitana, 9

- Bashir, Mohamed (2008). The arts of the Muslim knight; the Furusiyya Art Foundation collection. Skira. ISBN 978-88-7624-877-1

- Haarmann, Ulrich (1998), "The late triumph of the Persian bow: critical voices on the Mamluk monopoly on weaponry", The Mamluks in Egyptian politics and society, Cambridge University Press, pp. 174–187, ISBN 978-0-521-59115-7

- Nicolle, David (1999). Arms & Armour of the Crusading Era 1050–1350, Islam, Eastern Europe, and Asia. Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-369-6

- al-Sarraf, Shibab (2004), "Mamluk Furūsīyah Literature and Its Antecedents" (PDF), Mamlūk Studies Review, 8 (1): 141–201, ISSN 1086-170X

- Housni Alkhateeb Shehada, Mamluks and Animals: Veterinary Medicine in Medieval Islam (2012).

- Waterson, James (2007). The Knights of Islam: The Wars of the Mamluks. Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-734-2

External links

| Look up فروسية in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |