Fuegians

Fuegians are one of the three tribes of indigenous inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego,[1] at the southern tip of South America. In English, the term originally referred to the Yaghan people of Tierra del Fuego. In Spanish, the term fueguino can refer to any person from the archipelago.

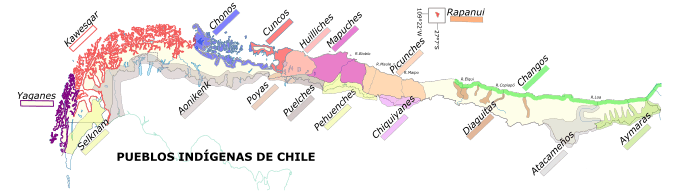

The indigenous Fuegians belonged to several different tribes including the Ona (Selk'nam), Haush (Manek'enk), Yaghan (Yámana), and Alacaluf (Kawésqar). All of these tribes except the Selk'nam lived exclusively in coastal areas and have their own languages. The Yaghans and the Alacaluf traveled by birchbark canoes around the islands of the archipelago, while the coast dwelling Haush did not. The Selk'nam lived in the interior of Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego and lived mainly by hunting guanacos. The Ona were exclusively terrestrial hunter gatherers that hunted terrestrial game such as guanacos, foxes, tuco-tucos and upland nesting birds as well as littoral fish and shellfish.[2] The Fuegian peoples spoke several distinct languages: both the Kawésqar language and the Yaghan language are considered language isolates, while the Selk'nams spoke a Chon language like the Tehuelches on the mainland.

European contact

In 1876 a serious smallpox epidemic decimated the Fuegians.[3] Between 1881 and 1883 the Yahgan population dropped from perhaps 3,000 to only 1,000 due to measles and smallpox.[4]

When Chileans and Argentines of European descent studied, invaded and settled on the islands in the mid-19th century, they brought with them diseases such as measles and smallpox for which the Fuegians had no immunity. The Fuegian population was devastated by the diseases, and their numbers were reduced from several thousand in the 19th century to hundreds in the 20th century.[5]

As early as 1878 Europeans in Punta Arenas seeking additional sheep pastures negotiated to acquire large tracts of land on Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego from the Chilean government just prior to Argentina and Chile's sovereignty here.[3]

By 1876 the British missionaries claimed to have converted the entire Yamana people.[3]

On May 11, 1830 several Fuegians (Alacaluf) were transported to England by the schooner Allen Gardiner, presented to the court, and resided there for a number of years before three were returned.[6]

The United States Exploring Expedition came in contact with the Fuegians in 1839. One member of the expedition called the Fuegians the "greatest mimics I ever saw."[7]

European genocide

The Selk'nam genocide was authorized and conducted by the estancieros that between 1884–1900 resulted in a severe indigenous population decline.[3] Large companies paid sheep farmers or militia a bounty for each Selk'nam dead, which was confirmed on presentation of a pair of hands or ears, or later a complete skull. They were given more for the death of a woman than a man.

Material culture

"Archaeological investigations show the prevalence of maritime hunter-gatherer organization throughout the occupation of the region (6400 BP – 19th century)."[8] Although the Fuegians were all hunter-gatherers,[9] their material culture was not homogeneous: the big island and the archipelago made two different adaptations possible. Some of the cultures were coast-dwelling, while others were land-oriented.[10][11] Neither was restricted to Tierra del Fuego:

- The coast provided fish, sea birds, otters, seals,[2] shellfish in winter[12] and sometimes also whales.[8][13] Yaghans got their sustenance this way. Alacalufs (living in the Strait of Magellan and some islands), and Chonos (living further to the north, on Chilean coasts and archipelagos) were similar.[10][11] Most whales were stranded but some whaling occurred.[14]

- Selk'nams lived on the inland plain of the big island of Tierra del Fuego, communally[15] hunting herds of guanaco.[10][11] The material culture had some similarities to that of the (also linguistically related) Tehuelches living outside Tierra del Fuego in the southern plains of Argentina.[10][16]

All Fuegian tribes had a nomadic lifestyle, and lacked permanent shelters. The guanaco-hunting Selk'nam made their huts out of stakes, dry sticks, and leather. They broke camp and carried their things with them, and wandered following the hunting and gathering possibilities. The coastal Yamana and Alacaluf also changed their camping places, traveling by birchbark canoes.[17]

Spiritual culture

Mythology

There are some correspondences or putative borrowings between the Yámana and Selk'nam mythologies.[18] The hummingbird was an animal revered by the Yámanas, and the Taiyin creation myth explaining the creation of the archipelago's water system, the culture hero "Taiyin" is portrayed in the guise of a hummingbird.[19] A Yámana myth, "The egoist fox", features a hummingbird as a helper and has some similarities to the Taiyin-myth of the Selk'nam.[20] Similar remarks apply to the myth about the big albatross: it shares identical variants for both tribes.[21] Some examples of myths having shared or similar versions in both tribes:

All three Fuegian tribes had myths about culture heroes.[24] Yámanas have dualistic myths about the two yoalox-brothers (IPA: [joalox]). They act as culture heroes, and sometimes stand in an antagonistic relation to each other, introducing opposite laws. Their figures can be compared to the Selk'nam Kwanyip-brothers.[25] In general, the presence of dualistic myths in two compared cultures does not necessaily imply relatedness or diffusion.[26]

Some myths also feature shaman-like figures with similarities in the Yámana and Selk'nam tribes.[27]

The abundant and nutritious patagonian blenny (Eleginops maclovinus) were apparently not consumed and the rock art suggests they may have had some religious significance.[28]

Shamanism

Both Selk'nam and Yámana had persons filling in shaman-like roles. The Selk'nams believed their xon (IPA: [xon]) to have supernatural capabilities, e.g. to control weather[29][30] and to heal.[31] The figure of xon appeared in myths, too.[32] The Yámana yekamush ([jekamuʃ])[33] corresponds to the Selk'nam xon.[27]

There are myths in both Yámána and Selk'nam tribes about a shaman using his power manifested as a whale. In both examples, the shaman was "dreaming" while achieving this.[34][35] For example, the body of the Selk'nam xon lay undisturbed while it was believed that he travelled and achieved wonderful deeds (e.g. taking revenge on a whole group of peoples).[21] The Yámana yekamush made similar achievements while dreaming: he killed a whale and led the dead body to arbitrary places, and transformed himself into a whale as well.[35] In another Selk'nam myth, the xon could use his power also for transporting whale meat. He could exercise this capability from great distances and see everything that happened during the transport.[36]

Gender

There is a belief in both the Selk'nam and Yámana tribes that women used to rule over men in ancient times,[25] Yámana attribute the present situation to a successful revolt of men. There are many festivals associated with this belief in both tribes.[37][38]

The patrilineal Ona and the composite band society Yahgan reacted very differently to the Europeans and it has been suggested that this was due to these facets of their cultural structure.[2]

Contacts between Yámana and Selk'nam

The principal differences in language, habitat, and adaptation techniques did not promote contacts, although eastern Yámana groups had exchange contacts with the Selk'nam.[18]

Language

The languages spoken by the Fuegians are all extinct, with the exception of the Yaghan language and Kawesqar. The Selk'nam language was related to the Tehuelche language and belonged to the Chon family of languages. The Onan language had more than 30,000 words.[1]

Alternative origin speculations

Alongside the Pericúes of Baja California, the Fuegians and Patagonians show the strongest evidence of partial descent from the Paleoamerican lineage,[39] a proposed early wave of migration to the Americas derived from a Australo-Melanesian population, as opposed to the main Amerind peopling of the Americas of Siberian (admixed Ancient North Eurasian and Paleo-East Asian) descent.[40][41] Further credibility is lent to this idea by research suggesting the existence of an ethnically distinct population elsewhere in South America.[42][43] According to archaeologist Ricardo E. Latcham the sea-faring nomads of Patagonia (Chonos, Kawésqar, Yaghan) may be remants from more widespread indigenous groups that were pushed south by "successive invasions" from more northern tribes.[44]

Modern history

The name "Tierra del Fuego" may refer to the fact that both Selk'nam and Yamana had their fires burn in front of their huts (or in the hut). In Magellan's time Fuegians were more numerous, and the light and smoke of their fires presented an impressive sight if seen from a ship or another island.[47] Yamanas also used fire to send messages by smoke signals, for instance if a whale drifted ashore.[48] The large amount of meat required notification of many people, so that it would not decay.[49] They might also have used smoke signals on other occasions, but it is possible that Magellan saw the smokes or lights of natural phenomena.[50]

Both Selk'nams and Yámanas were decimated by diseases brought in by colonization,[2][51] and probably made more vulnerable to disease by the crash of their main meat supplies (whales and seals) due to the actions of European and American fleets.[2]

See also

- Selk'nam genocide

- Anne Chapman

- Fuegian languages

- Indigenous Amerindian genetics

- Thomas Bridges

- Julius Popper

Notes

- Oyola-Yemaiel, Arthur (1999). The Early Conservation Movement in Argentina and the National Park Service. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 9781581120981. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Cordell, Stephen Beckerman, Linda S; Beckerman, Stephen (2014). The Versatility of Kinship: Essays Presented to Harry W. Basehart. ISBN 9781483267203. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Chapman, Anne (2010). European Encounters with the Yamana People of Cape Horn, Before and After Darwin. Cambridge. p. 471. ISBN 9780521513791. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Cook, Noble David (2004). Demographic Collapse: Indian Peru, 1520–1620. Cambridge. ISBN 9780521523141. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Die letzten Feuerland-Indianer / Ein Naturvolk stirbt aus. (Short article in German, with title “The last Fuegians / An indigenous people becomes extinct”). Archived from the original.

- Snow, William Parker (2013). A Two Years' Cruise Off Tierra Del Fuego, the Falkland Islands, Patagonia, and in the River Plate: A Narrative of Life in the Southern Seas. ISBN 9781108062053. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Stanton, William (1975). The Great United States Exploring Expedition. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 104–107. ISBN 978-0520025578.

- Tivoli, Angélica M.; Zangrando, A. Francisco (2011). "Subsistence variations and landscape use among maritime hunter-gatherers. A zooarchaeological analysis from the Beagle Channel (Tierra del Fuego, Argentina)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 38 (5): 1148–1156. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.12.018.

- Gusinde 1966:6–7

- Service 1973:115

- Extinct Ancient Societies Tierra del Fuegians

- Colonese (2012). "Oxygen isotopic composition of limpet shells from the Beagle Channel: implications for seasonal studies in shell middens of Tierra del Fuego". Journal of Archaeological Science. 39 (6): 1738–1748. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.01.012.

- Briz, Ivan; Álvarez, Myrian; Zurro, Débora; Caro, Jorge. "Meet for lunch in Tierra del Fuego: a new ethnoarchaeological project". Antiquity. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Chapman, Anne (1982). Drama and Power in a Hunting Society: The Selk'nam of Tierra Del Fuego. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521238847. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Davis, Leslie B.; Reeves, Brian O.K (2014). Hunters of the Recent Past. ISBN 9781317598350. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Gusinde 1966:5

- Gusinde 1966:7

- Gusinde 1966:10

- Gusinde 1966:175–176

- Gusinde 1966:183

- Gusinde 1966:179

- Gusinde 1966:178

- Gusinde 1966: 182

- Gusinde 1966:71

- Gusinde 1966:181

- Zolotarjov 1980:56

- Gusinde 1966:186

- Fiore, Danae; Francisco, Atilio; Zangrando, J. (2006). "Painted fish, eaten fish: Artistic and archaeofaunal representations in Tierra del Fuego, Southern South America". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 25 (3): 371–389. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2006.01.001.

- Gusinde 1966:175

- "About the Ona Indian Culture in Tierra del Fuego". Archived from the original on 2015-06-14. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- Gusinde 1966:67

- Gusinde 1966:15

- Gusinde 1966:156

- Gusinde 1966:64

- Gusinde 1966:155

- Gusinde 1966:61

- Gusinde 1966:184

- Service 1973:116–117

- González-José, R. et al., "Craniometric evidence for Palaeoamerican survival in Baja California", Nature vol. 425 (2003), 62–65. "A current issue on the settlement of the Americas refers to the lack of morphological affinities between early Holocene human remains (Palaeoamericans) and modern Amerindian groups, as well as the degree of contribution of the former to the gene pool of the latter. A different origin for Palaeoamericans and Amerindians is invoked to explain such a phenomenon. Under this hypothesis, the origin of Palaeoamericans must be traced back to a common ancestor for Palaeoamericans and Australians, which departed from somewhere in southern Asia and arrived in the Australian continent and the Americas around 40,000 and 12,000 years before present, respectively. Most modern Amerindians are believed to be part of a second, morphologically differentiated migration. [...] The principal coordinate plot obtained using the matrix of minimum genetic distances (Fig. 1a) showed that BCS [Baja California series] was closely linked with Palaeoamericans, whereas the populations from Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego showed an intermediate position between classical Amerindians and/or East Asians and Palaeoamericans".

- Gamble, Clive (September 1992). "Archaeology, history and the uttermost ends of the earth – Tasmania, Tierra del Fuego and the Cape". Antiquity. 66 (252): 712–720. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00039429. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- "First Americans were Australian". BBC News. 1999-08-26. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- Neves, WA; Prous A; González-José R; Kipnis R; Powell J. "Early Holocene human skeletal remains from Santana do Riacho, Brazil: implications for the settlement of the New World". J Hum Evol (2003 Jul 45(1):19–42).

- "Fuegian and Patagonian Genetics – and the settling of the Americas" Archived 2013-05-05 at the Wayback Machine, by George Weber.

- Trivero Rivera, Alberto (2005). Los primeros pobladores de Chiloé: Génesis del horizonte mapuche (in Spanish). Ñuque Mapuförlaget. p. 41. ISBN 91-89629-28-0.

- Odone, C. and M.Palma, 'La muerte exhibida fotografias de Julius Popper en Tierra del Fuego', in Mason and Odone, eds, 12 miradas. Culturas de Patagonia: 12 Miradas: Ensayos sobre los pueblos patagonicos', Cited in Mason, Peter. 2001. The lives of images. P.153

- Ray, Leslie. 2007. "Language of the land: the Mapuche in Argentina and Chile ". P.80

- Itsz 1979:97

- Gusinde 1966:137–139, 186

- Itsz 1979:109

- The Patagonian Canoe. Extracts from the following book. E. Lucas Bridges: Uttermost Part of the Earth. Indians of Tierra del Fuego. 1949, reprinted by Dover Publications, Inc (New York, 1988).

- Itsz 1979:108,111

References

- Gusinde, Martin (1966). Nordwind—Südwind. Mythen und Märchen der Feuerlandindianer (in German). Kassel: E. Röth. Title means: “North wind—south wind. Myths and tales of Fuegians”.

- Itsz, Rudolf (1979). Napköve. Néprajzi elbeszélések (in Hungarian). Budapest: Móra Könyvkiadó. Translation of the original: Итс, Р.Ф. (1974). Камень солнца (in Russian). Ленинград: Издательство «Детская Литература». Title means: “Stone of sun”; chapter means: “The land of burnt-out fires”.

- Service, Elman R. (1973). "Vadászok". In E.R. Service & M.D. Sahlins & E.R. Wolf (ed.). Vadászok, törzsek, parasztok (in Hungarian). Budapest: Kossuth Könyvkiadó. It contains the translation of the original: Service, Elman (1966). The Hunter. Prentice-Hall.

- Zolotarjov, A.M. (1980). "Társadalomszervezet és dualisztikus teremtésmítoszok Szibériában". In Hoppál, Mihály (ed.). A Tejút fiai. Tanulmányok a finnugor népek hitvilágáról (in Hungarian). Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó. pp. 29–58. ISBN 978-963-07-2187-5. Chapter means: “Social structure and dualistic creation myths in Siberia”; title means: “The sons of Milky Way. Studies on the belief systems of Finno-Ugric peoples”.

Further reading

- Vairo, Carlos Pedro (2002) [1995]. The Yamana Canoe: The Marine Tradition of the Aborigines of Tierra del Fuego. ISBN 978-1-879568-90-7.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article "Fuegians". |

- Videos

- Balmer, Yves (2003–2009). "Fuegian Videos". Ethnological videos clips. Living or recently extinct traditional tribal groups and their origins. Andaman Association. Archived from the original on 2009-07-12. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- Audio

- Lola Kiepja. Selk'nam (Ona) Chants of Tierra del Fuego, Argentina (Streamed tracks on Napster from the audio CD)).

- Excerpts from the same material on Amazon.com

- Bibliography, linking many online documents in various languages

- English

- Extinct Ancient Societies Tierra del Fuegians

- Indians page of homepage of Museo Maritiomo de Ushuaia

- German

- Dr Wilhelm Koppers: Unter Feuerland-Indianern. Strecker und Schröder, Stuttgart, 1924. (A whole book online. In German. Title means: “Among Fuegians”.)

- Die letzten Feuerland-Indianer / Ein Naturvolk stirbt aus. (Short article in German, with title “The last Fuegians / An indigenous people becomes extinct”)

- Feuerland — Geschichten vom Ende der Welt. (“Tierra del Fuego — stories from the end of the world”. Link collection with small articles. In German.)

- erdrand galleries, 9 photos

- Spanish

- Cosmología y chamanismo en Patagonia by Beatriz Carbonell. See abstract in English.

- Shaman-like figures (Selk'nam [xon], Yámana [jekamuʃ])

- About the Ona Indian Culture in Tierra del Fuego

- Rituals and beliefs of the Yámana, mentioning “yekamush”

- (in Spanish) Cosmología y chamanismo en Patagonia by Beatriz Carbonell. See abstract in English.