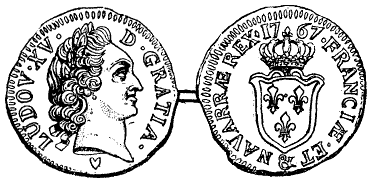

French sol

The sol, later called a sou, is the name of a number of different coins, for accounting or payment, dating from Antiquity to today. The name is derived from the solidus. Its longevity of use anchored it in many expressions of the French language.

Roman antiquity

The solidus is a coin made of 4.5 g of gold, created by emperor Constantine to replace the aureus.

Early Middle Ages

Doing honour to its name, the new currency earns the reputation of unalterability, crossing almost unchanged the decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire, the great invasions and the creation of Germanic kingdoms throughout Europe; not only was it issued in the Byzantine empire until the 11th century under the name of nomisma, but the solidus was imitated by the barbarian kings, particularly the Merovingians, albeit most often in the form of a "third of a sou" (tremissis).

.jpg)

Facing a shortage of gold, a new "stabilization" (as devaluations are often called) is introduced by Charlemagne: from then on the solidus no longer represents 1/12th of the Roman gold pound but 1/20th of the Carolingian silver pound instead. The sou itself is divided into 12 denarii and one denarius is worth 10 asses. But for rare exceptions (saint Louis' "gros"), the denarius will in practice be the only ones in circulation.[1]

Charlemagne's general principle of 12 denarii worth one sol and of twenty sols worth one pound is kept with many variants according to the alloy used and the dual metal gold:silver sometimes used for some issues. In fact, only members of the money changers corporation could find their way among the equivalences and the many currencies used in Europe at each period, and therefore were unavoidable for many commercial operations.

Late Middle Ages

The name evolves as does the rest of the language, from Latin to French. Solidus becomes soldus, then solt in the 11th century, then sol in the 12th century. In the 18th century (Ancien Régime) the spelling of sol is adapted to sou so as to be closer to the pronunciation that had previously become the norm for several centuries.

Abolition and Legacy

In 1795, the livre was officially replaced by the franc and the sou became obsolete as an official currency division. Nevertheless, the term "sou" survived as a slang term for 1/20 of a franc. Thus the large bronze 5-centime coin was called "sou" (for example in Balzac or Victor Hugo), the "pièce de cent sous" ("hundred sous coin") meant five francs and was also called "écu" (as in Zola's Germinal). The last 5-centime coin, remote souvenir inherited from the "franc germinal", is removed from circulation in the 1940s, but the word "sou" keeps being used (except for the 1960 new franc's five-centime coin which was worth five old francs).

Sous outside France

Canada

In Canada, the word "sou" is used in everyday language and means the division of the Canadian dollar. The official term is "cent". The one cent coins have the vernacular name of "sou noir" ("black sou") and the 25 cents that of "thirty sous". "Échanger quatre trente sous pour une piastre" ("to exchange four 30 sous for one piastre") therefore means changing something for an identical thing, as the "piastre" is the common name for the Canadian dollar.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, a hundred-sou coin is a five-Swiss-franc coin and a four-sou coin is a twenty-Swiss-centime coin. The word sou also remains in informal language in the terms "ten, twenty ... sous".

The sou in French expressions

Used for over a thousand years, the word "sou" is deeply rooted in the French language and expressions. Les sous, plural, is a synonym for money.

« Se faire des sous », to make money.

- «Une affaire de gros sous » is big money business.

- « Être sans le sou », « ne pas avoir sou vaillant », « n'a pas un sou en poche », « n'avoir ni sou ni maille »:[2] "not having one penny", having no money at all.

- About one who is always short of money or always asking for some, one says that « Il lui manque toujours 3 sous pour faire un franc » ("he always lacks 3 sous to make up to one franc"). Sometimes it is said "missing 19 sous to have one franc", with one franc worth 20 sous; U.S. version: "he always needs a penny to have a round dollar".

- « Je te parie cent sous contre un franc » ("I bet you 100 sous (5 francs) for 1 franc"), meaning "I am sure about (whatever the topic is)".

- « Un sou est un sou », there is no small profit, equivalent to "a penny saved is a penny earned".

- « Sou par sou » or « sou à sou », little by little.

- « Être près de ses sous » ("to be near one's money"), to be avaricious/tight-fisted.

- « On lui donnerait cent sous à le voir », "one would give him 100 sous upon sight", for someone whose appearance inspires pity.

- « S'ennuyer « à cent sous l'heure » or « à cent sous de l'heure », being very bored.

- When something is worth « trois francs six sous », it is very cheap.

- « Un objet de quatre sous » ("a two-penny item") is of even lesser value, thus the "3 Groschen Opera from Brecht has become "l'Opéra de 4 sous".

- When one « n'a pas deux sous de jugeote », one "doesn't have an ounce of common sense".

- A « machine à sous » is a hole in the wall (an ATM—its slightly more formal name is "distributeur").

- « Le sou du franc » ("the penny off the pound"), a sweetener for a buyer.

- « Pas ambigu/fier/modeste/courageux/... pour un sou » is "not at all ambiguous/proud/modest/courageous/...".

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Solidus. |

- Solidus (coin)

- Roman and Byzantine coinage

- Bezant

- Nomisma

- Hoxne Hoard

- Solidus and slash punctuation marks

References

- Charlemagne - The Middle Ages Archived 2017-11-09 at the Wayback Machine on themiddleages.net.

- A "maille" is half a denarius.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roman currency. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.