Frankish mythology

Frankish mythology comprises the mythology of the Germanic tribal confederation of the Franks, from its roots in polytheistic Germanic paganism through the inclusion of Greco-Roman components in the Early Middle Ages. This mythology flourished among the Franks until the conversion of the Merovingian king Clovis I to Nicene Christianity (c. 500), though there were many Frankish Christians before that. After that, their paganism was gradually replaced by the process of Christianisation, but there were still pagans in the Frankish heartland of Toxandria in the late 7th century.

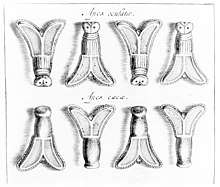

Golden cicadas or bees with garnet inserts, discovered in the tomb of Childeric I (died 482). They may have symbolised eternal life (cicadas) or longevity (the bees of Artemis).[1]

Pre-Christian traditions

The majority of pagan Frankish beliefs may share similarities with that of other Germanic peoples. If so, then it may be possible to reconstruct the basic elements of Frankish traditional religion.[2]

The migration era religion of the Franks likely shared many of its characteristics with the other varieties of Germanic paganism, such as placing altars in forest glens, on hilltops, or beside lakes and rivers, and consecration of woods.[3] Generally, Germanic gods were associated with local cult centres and their sacred character and power were associated with specific regions, outside of which they were neither worshipped nor feared.[4] Other deities were known and feared and shared by cultures and tribes, although in different names and variations. Of the latter, the Franks may have had one omnipotent god Allfadir ("All Father"), thought to have lived in a sacred grove. Germanic peoples may have gathered where they believed him to live, and sacrificed a human life to him.[5] Variants of the phrase All Father (like Allfadir) usually refer to Wuotan (Woden, Óðinn/Odin), and the Franks probably believed in Wuoton as "chief" of blessings, whom the first historian Tacitus called "Mercurius", and his consort Freia,[6] as well as Donar (Thor), god of thunder, and Zio (Tyr), whom Tacitus called "Mars". According to Herbert Schutz, most of their gods were "worldly", possessing form and having concrete relation to earthly objects, in contradistinction to the transcendent God of Christianity.[4] Tacitus also mentioned a goddess Nerthus being worshipped by the Germanic people, in whom Perry thinks the Franks may have shared a belief.[7] With the Germanic groups along the North Sea the Franks shared a special dedication to the worship of Yngvi, synonym to Freyr, whose cult can still be discerned in the time of Clovis.[8]

In contrast to many other Germanic tribes, no Merovingians claimed to be descended from Wodan.[9]

Some rich Frankish graves were surrounded by horse burials, such as Childeric's grave.

Symbolism of cattle

The bulls that pulled the cart were taken as special animals, and according to Salian law the theft of those animals would impose a high sanction. Eduardo Fabbro has speculated that the Germanic goddess Nerthus (who rode in a chariot drawn by cows) mentioned by Tacitus, was the origin of the Merovingian conception of Merovech, after whom their dynasty would be named. The Merovingian kings riding through the country on an oxcart could then be an imaginative reenactment the blessing journey of their divine ancestor.[10] In the grave of Childeric I (died 481) was found the head of a bull, craftily made out of gold. This may have represented the symbol of a very old fertility ritual,[11] that centred on the worship of the cow. According to Fabbro, the Frankish pantheon expressed a variation of the Germanic structure that was especially devoted to fertility gods.[2]

However, a more likely explanation is that the Merovingian ox-cart went back to the Late-Roman tradition of governors riding through the province to dispense justice in the company of angariae, or ox wagons belonging to the imperial post.[12] [13] The bull in Childeric's grave was probably an insignificant object imported from elsewhere, and belongs to a wide artistic usage of bulls in pre-historic European art.[13]

Foundation myth

The Frankish mythology that has survived in primary sources is comparable to that of the Aeneas and Romulus myths take in Roman mythology, but altered to suit Germanic tastes. Like many Germanic peoples, the Franks told a founding myth story to explain their connection with peoples of classical history. In the case of the Franks, these people were the Sicambri and the Trojans. An anonymous work of 727 called Liber Historiae Francorum states that following the fall of Troy, 12,000 Trojans led by chiefs Priam and Antenor moved to the Tanais (Don) river, settled in Pannonia near the Sea of Azov and founded a city called "Sicambria". In just two generations (Priam and his son Marcomer) from the fall of Troy (by modern scholars dated in the late Bronze Age) they arrive in the late 4th century AD at the Rhine. An earlier variation of this story can be read in Fredegar. In Fredegar's version an early king named Francio serves as namegiver for the Francs, just as Romulus has lent his name to Rome.

These stories have obvious difficulties if taken as fact. Historians, including eyewitnesses like Caesar, have given us accounts that places the Sicambri firmly at the delta of the Rhine and archaeologists have confirmed ongoing settlement of peoples. Furthermore, the myth does not come from the Sicambri themselves, but from later Franks (of the Carolingian age or later), and includes an incorrect geography. For these reasons, and since the Sicambri were known to have been Germanic, current scholars think that this myth was not prevalent, certainly not historical: For example, J. M. Wallace-Hadrill states that "this legend is quite without historical substance".[14] Ian Wood says that "these tales are obviously no more than legend" and "nonsensical", "in fact there is no reason to believe that the Franks were involved in any long-distance migration".[12]

In Roman and Merovingian times it was customary to declare panegyrics. These poetical declarations were held for amusement or propaganda, to entertain guests and please rulers. Panegyrics played an important role in the transmission of culture. A common panegyrical device was anachronism, the use of archaic names for contemporary things. Romans were often called "Trojans" and Salian Franks were called "Sicambri". A notable example related by the sixth-century historian Gregory of Tours states that the Merovingian Frankish leader Clovis I, on the occasion of his baptism into the Catholic faith, was referred to as a Sicamber by Remigius, the officiating bishop of Rheims.[15] At the crucial moment of Clovis' baptism, Remigius declared, "Bend down your head, Sicamber. Honour what you have burnt. Burn what you have honoured." It is likely that in this way a link between the Sicambri and the Salian Franks, who were Clovis' people, was being invoked. Further examples of Salians being called Sicambri can be found in the Panegyrici Latini, the Life of King Sigismund, the Life of King Dagobert, and other sources.

Sacral kingship

The religion of Clovis before his adherence to Catholic faith has been disputed,[16][17] and he may have doubted between Catholicism and Arianism for a while.[12]

Pagan Frankish rulers probably maintained their elevated positions by their "charisma" or Heil, their legitimacy and "right to rule" may have been based on their supposed divine descent as well as their financial and military successes.[4][18] The concept of "charisma" has been controversial.[19]

Fredegar tells a story of the Frankish king Chlodio taking a summer bath with his wife when she was attacked by some sort of sea beast, which Fredegar described as bestea Neptuni Quinotauri similis, ("the beast of Neptune that looks like a Quinotaur"). Because of the attack, it was unknown if Merovech, the legendary founder of the Merovingian dynasty was conceived of Chlodio or the sea beast.[20]

In later centuries, divine kingship myths would flourish in the legends of Charlemagne (768–814) as a divinely-appointed Christian king. He was the central character in the Frankish mythology of the epics known as the Matter of France. The Charlemagne Cycle epics, particularly the first, known as Geste du Roi ("Songs of the King"), concern a King's role as champion of Christianity. From the Matter of France, sprang some mythological stories and characters adapted through Europe, such as the knights Lancelot and Gawain.

Notes

- For cicadas, cf. Joachim Werner, "Frankish Royal Tombs in the Cathedrals of Cologne and Saint-Denis", Antiquity, 38:151 (1964), 202; for bees, cf. G. W. Elderkin, "The Bee of Artemis", The American Journal of Philology, 60:2 (1939), 213.

- Fabbro, p. 5.

- Perry, p. 22.

- Schutz, 153.

- Perry, p. 22-23, paraphrasing Tacitus.

- Perry, p. 23.

- Perry, p. 24.

- Fabbro, p.17

- J.M. Wallace-Hadrill - Early Germanic Kingship in England and on the Continent. London, Oxford University Press.1971, p. 18.

- Fabbro, p. 16

- Fabbro, p.14

- Wood, p. 33-54.

- Alexander Callander Murray, 'Post vocantur Merohingii: Fredegar, Merovech, and "sacred kingship", in: idem ed., After Rome's Fall: Narrators and Sources of early medieval history. Essays presented to Walter Goffart (Toronto 1998) p.125

- Wallace-Hadrill p. ???

- Gregory, II.31.

- Tessier, p. 427.

- Daly, pp. ???.

- Wallace-Hadrill, 169.

- Schutz, 232 n49.

- Pseudo-Fredegar, III.9.

References

Primary

- Pseudo-Fredegar. Historia, in Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores Rerum Merovingicarum, Tomus II. Hannover: 1888.

- Gregory of Tours. The History of the Franks. Lewis Thorpe, trans. Penguin Group. ISBN 0-14-044295-2.

- Publius Cornelius Tacitus. Germania.

Secondary

- Daly, William M. "Clovis: How Barbaric, How Pagan?" Speculum, vol. 69, no. 3 (July 1994), pp. 619–664.

- Fabbro, Eduardo. "Germanic Paganism among the Early Salian Franks." The Journal of Germanic Mythology and Folklore. Volume 1, Issue 4, August 2006.

- Murray, Archibald Callander, and Goffart, Walter A. After Rome's Fall: Narrators and Sources of Early Medieval History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998.

- Nelson, Janet L. "Royal Saints and Early Medieval Kingship." Studies in Church History, 10 (1973), pp. 39–44. Reprinted in Politics and Ritual in Early Medieval Europe. Janet L. Nelson, ed. London: Hambledon Press, 1986. pp. 69–74. ISBN 0-907628-59-1.

- Perry, Walter Copland. The Franks, from Their First Appearance in History to the Death of King Pepin. Longman, Brown, Green: 1857.

- Prummel, W., and van der Sanden, W. A. B. "Runderhoorns uit de Drentse venen." Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak, 112. 1995. pp. 84–131.

- Prummel, W., and van der Sanden, W. A. B.. "Een oeroshoren uit het Drostendiep bij Dalen." Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak, 119. 2002. pp. 217–221.

- Raemakers, Daan. De Spiegel van Swifterbant. Groningen: 2006.

- Schutz, Herbert. The Germanic Realms in Pre-Carolingian Central Europe, 400–750. American University Studies, Series IX: History, Vol. 196. New York: Peter Lang, 2000.

- Tessier, Georges. Le Baptême de Clovis. Paris: Gallimard, 1964.

- Wallace-Hadrill, J. M. The Long-Haired Kings. London: Butler & Tanner Ltd, 1962.

- Wood, Ian. The Merovingian Kingdoms, 450-751 AD. 1994.