Francesco Sforza Pallavicino

Francesco Maria Sforza Pallavicino (or Pallavicini) (28 November 1607, Rome – 5 June 1667, Rome), was an Italian cardinal and historian of the Council of Trent. He used the name Sforza Pallavicino as an author and is often incorrectly identified as Pietro Sforza Pallavicino.[1][2]

Sforza Pallavicino | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Cardinal Sforza Pallavicino | |

| Diocese | Diocese of Rome |

| Appointed | 1 April 1657 |

| Term ended | 5 June 1667 |

| Orders | |

| Created cardinal | 9 April 1657 by Pope Alexander VII |

| Rank | Cardinal-Priest |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 28 November 1607 Rome, Papal States |

| Died | 5 June 1667 Rome |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

Life

Pallavicino was born in Rome. He was son of the Marquis Alessandro Pallavicino, the adopted son of Sforza Pallavicino marchese di Cortemaggiore, a famous Italian condottiero, Captain-General of the Republic of Venice,[3] and his second wife, Francesca Sforza di Santa Fiora, widow of Ascanio della Penna della Cornia.

Descended from the line of Parma of the ancient and noble house of the Marchesi Pallavicini, his father's first-born son, he renounced the right of primogeniture and resolved to enter the priesthood. He entered the Roman College, where he devoted himself to the study of philosophy and law.

Career

He earned doctorates in philosophy in 1625, and in theology in 1628, having studied under the famous Spanish theologian John de Lugo. Pope Urban VIII appointed him referendarius utriusque signaturæ and member of the Congregatio boni regiminis and of the Congregatio immunitatis, assigning him a pension of 250 scudi.

Pallavicino was highly esteemed in the literary circles of Rome. He was elected Member of the Accademia degli Umoristi and became friends with the poet Virginio Cesarini and with some of the most prominent personalities of italian baroque, including Agostino Mascardi, Fulvio Testi, John Barclay and Giulio Strozzi. Alessandro Tassoni praised him in a verse of his mock-heroic poem La secchia rapita.

On 27 January 1629 Pallavicino became a Member of the Accademia dei Lincei , together with Lucas Holstenius and Pietro della Valle.[4]

When his friend Giovanni Ciampoli, the secretary of briefs, fell into disfavour, Pallavicino's standing at the papal court was also seriously affected. He was sent in 1632 as governatore to Jesi, Orvieto, and Camerino, where he remained for a considerable time.

Over his father's objections, he entered the Society of Jesus on 21 June 1637. After the two years' novitiate he became professor of philosophy at the Roman College.[5] In 1643, when John de Lugo was made a cardinal, Pallavicino succeeded him in the chair of theology, a position he held until 1651 while also fulfilling assignments for Pope Innocent X. These included appointments as a member of the commissions that examined the writings of Jansenius and Martin de Barcos, which resulted in the condemnation of two works by de Barcos in 1647.

On 3 February 1665 Pallavicino entered the Accademia della Crusca,[6] an association of scholars and writers devoted to the Italian language.

On 9 April 1657 Pallavicino was made a cardinal in pectore by Pope Alexander VII who made the appointment public in 1659. Pallavicino died in Rome on 5 June 1667, at the age of sixty.[7]

His other writings include Trattato dello Stile, Vindication. Soc. Jes., and Del Bene[8] which latter was later praised by the Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce for its contribution to the development of modern aesthetics.[9]

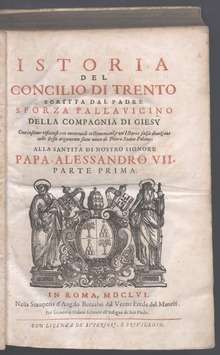

History of the Council of Trent

Pallavicino is chiefly known by his History of the Council of Trent, a harsh if well researched rebuttal to Paolo Sarpi's Istoria del Concilio Tridentino.[5] The work was published at Rome in two folio volumes in 1656-1657 (2nd ed., considerably modified, in 1666). In this he continued the task begun by Terenzio Alciati, who had been commissioned by Pope Urban VIII to correct and supersede the very damaging work of Sarpi. Alciati and Pallavicino had access to many important sources which had been denied to Sarpi.

The great nineteenth-century historian Leopold von Ranke reported that he examined many of the manuscript sources from which Pallavicino drew his materials, and that the extracts he has made from the instructions and other official documents were "scrupulously exact" and that he has "carefully consulted the whole of the documents".[10] Until the twentieth century, Pallavicino's History of the Council of Trent was the principal work on this important ecclesiastical assembly. It was translated into Latin by a fellow Jesuit, Giattini (Antwerp, 1670-1673), into French (Migne series, Paris, 1844-1845); into Spanish and into German by Theodor Friedrich Klitsche de la Grange (1835-1837). There is a good edition of the original by Francesco Antonio Zaccaria (6 vols., Faenza, 1792-1799).

Original publication

- Pallavicino, Francesco Sforza (1656). Istoria del concilio di Trento. Parte prima. In Roma: nella stamperia d'Angelo Bernabò dal Verme erede del Manelfi : per Giovanni Casoni libraro.

- Pallavicino, Francesco Sforza (1657). Istoria del concilio di Trento. Parte seconda. In Roma: nella stamperia d'Angelo Bernabò dal Verme erede del Manelfi : per Giovanni Casoni libraro.

References

- Pallavicino's first name is not Pietro, a mistake often found even in scholarly literature. See Apollonio, "Sul nome del Padre (non Pietro) Sforza Pallavicino", Studi Secenteschi, LIV (2013), pp. 335-341.

- "PALLAVICINO, Francesco Maria Sforza". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). 80. Instituto Giovanni Treccani. 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

Il nome proprio di Pallavicino è stato oggetto di equivoco già lui vivente, generato dalla rarità del nome proprio ‘Sforza’ e dall’omonimo cognome materno. Nel corso del Novecento la situazione si è ulteriormente complicata per la comparsa – nelle biografie, nei repertori e in testa alle riedizioni delle sue opere – di un presunto nome ‘Pietro’, non confermato da alcun documento. Il nome da lui comunemente usato nella vita pubblica e privata era Sforza (Apollonio, 2013)." Translation: "Pallavicino's correct name was misunderstood even during his lifetime, generated by the rarity of the proper name 'Sforza' and the homonymous maternal surname. In the twentieth century the situation was further complicated by the appearance, in biographies, in bibliographies, and on the title pages of his reissued works, of a presumed name 'Pietro' that no document supports. The name he commonly used in both his public and private life was Sforza (Apollonius, 2013).

- Seletti, Emilio (1883). La città di Busseto, capitale un tempo dello stato Pallavicino (in Italian). 1. Milan. pp. 67ff.

- The Art of Religion: Sforza Pallavicino and Art Theory in Bernini's Rome, Maarten Delbeke, Routledge, 2016,

- Infinitesimal, Amir Alexander, Oneworld Publications, 2014, p. 145.

- "Pallavicino, Sforza <1607-1667>". December 5, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- "PALLAVICINO, S.J., Francesco Maria Sforza (1607-1667)". Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- An Universal, Historical, Geographical, Chronological and Poetical Dictionary, 1703, .

- Benedetto Croce:, I trattatisti italiani del "concettismo" e Baltasar Graciàn, in: Atti e memorie dell'Accademia Pontaniana, Napoli 1899, pp. 1-32; see also his Storia dell'Età Barocca in Italia, Milano 1993 (1929), pp. 240-251.

- "Fra. Paolo Sarpi". The Dublin Review. 66: 364. 1870.

- Sources

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1911). . Catholic Encyclopedia. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

- "PALLAVICINO, S.J., Francesco Maria Sforza (1607-1667)". Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- Sforza Pallavicino in the Historical Archives of the Pontifical Gregorian University

- British Library database of Italian Academies, for Pallavicino's membership of the Accademia dei Desiosi and links with other intellectuals

Bibliography

- Leo Allatius (1633). Apes urbanae. Romae: excudebat Ludovicus Grignanus. pp. 233–234.

- Ireneo Affò (1794). Memorie della vita e degli studj del Cardinale Sforza Pallavicino (3 ed.). Parma: Stamperia reale.

- Leopold von Ranke, Geschichte der römischen Päpste, ii, pp. 237 sqq.; 3, Appendix;

- Johann Nepomuk Brischar, Beurtheilung der Controversen Sarpi's und Pallavicini's (Tubingen 1844);

- Theodore Alois Buckley, History of the Council of Trent (London 1852), Preface;

- Hugo von Hurter (1910). Nomenclator literarius. IV. Innsbruck. p. 192.

- Pietro Giordani, Opera inedita del P. Sforza Pallavicino in Vita di Alessandro VII, I (Prato, 1839), 3 sqq.

- Johann Traugott Leberecht Danz, Geschichte des Tridentinischen Concils (Jena, 1846, 8vo), Preface.

- Girolamo Tiraboschi. Storia della letteratura italiana. 8. pp. 132–136.

- Carlos Sommervogel, Bibliothèque de la Compagnie de Jésus, VI, Bibliography (new edition, Brussels, 1895), 120-143;

- Benedetto Croce (1929). Storia dell'età barocca in Italia. Bari: Casa editrice Giuseppe Laterza & figli. pp. 183–188.

- Hubert Jedin (1948). Das Konzil von Trient: Ein Überblick über die Erforschung seiner Geschichte (in German). Roma: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura. pp. 119–145.

- László Polgár, Bibliographie sur l'histoire de la Compagnie de Jésus, III, Roma 1990, pp. 615-617;

- Domenico Bertoloni Meli, Shadows and deception: from Borelli's Theoricae to the Saggi of the Cimento, in The British Journal for the History of Science, XXXI (1998), pp. 401-404.

- Sven K. Knebel (2001). "Pietro Sforza Pallavicino's Quest for Principles of Induction". The Monist. 84 (4): 502–519. JSTOR 27903746.

- Maarten Delbeke (2002). La fenice degl'ingegni: een alternatief perspectief op Gianlorenzo Bernini en zijn werk in de geschriften van Sforza Pallavicino. Ghent University Architectural and Engineering Press.

- Jacob Schmutz, «Aristote au Vatican. Le débat entre Pietro Sforza Pallavicino (1606-1667) et Frans Vanderveken (1596-1664) sur la théorie aristotélicienne de la vérité», in: Der Aristotelismus in der frühen Neuzeit, Kontinuität oder Wiederaneignung ?, Frank, Günter; Speer, Andreas (eds.), Wiesbaden : Harrassowitz, 2007, 65-95;

- Maarten Delbeke (2012). The Art of Religion: Sforza Pallavicino and Art Theory in Bernini's Rome. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1409458852.