First Amendment audits

First Amendment audits are a largely American social movement that usually involves photographing or filming a public space. It is often categorized by its practitioners, known as auditors, as activism and citizen journalism that tests constitutional rights;[1] in particular the right to photograph and video record in a public space.[2][3] Auditors believe that the movement promotes transparency and open government.[4] However, audits are often confrontational in nature, as auditors often refuse to self-identify or explain their activities.[5][6] Some auditors have also been known to enter public buildings asserting that they have a legal right to openly carry, leading to accusations that auditors are engaged in intimidation, terrorism, and the sovereign citizen movement.[7][8][9]

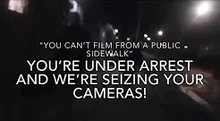

Auditors tend to film or photograph government buildings, equipment, access control points and sensitive areas, as well as recording law enforcement or military personnel present.[10] Auditors have been unlawfully detained, arrested, assaulted, had camera equipment confiscated, weapons aimed at them, had their homes raided by a SWAT team, and been shot for video recording in a public place.[11][12][13][14][15][16] Such events have prompted police officials to release information on the proper methods of handling such an activity.[17][18] For example, a document sponsored by the International Association of Chiefs of Police states that the use of a recording device alone is not grounds for arrest, unless other laws are violated.[19]

The practice is predominantly an American concept, but it has also been seen in other countries including the United Kingdom[20] and India.[21]

Behaviour

Auditors typically travel to a place that is considered public property, such as a sidewalk or public easement, or a place open to the public, such as a post office or government building, and visibly and openly photograph and record buildings and persons in their view.[22]

In the case of sidewalk or easement audits, the conflict arises when a property owner or manager states, in substance, that photography of their property is not allowed. Sometimes, auditors will tell property owners upon questioning that they are photographing or recording for a story, they are photographing or recording for their "personal use", or sometimes auditors do not answer questions.[23][24] Frequently, local law enforcement is called and the Auditor is sometimes reported as a suspicious person. Some officers will approach the auditors and request his or her identification and an explanation of their conduct. Almost universally, auditors will refuse to identify themselves and occasionally quote the relevant law to the officer as the basis for their refusal to self-identify.[6][25] This sometimes results in officers arresting auditors for failing to identify themselves, obstruction of justice, disorderly conduct, or any potential or perceived crime that could potentially be justified by the occasion.[26][27]

Legality

The act of recording in public was established in the United States following the case of Glik v. Cunniffe,[28] which confirmed that restricting a person's right to film in public would violate their First and Fourth amendment rights. As the 7th Circuit Federal Court of Appeals explained in ACLU v. Alvarez, "[t]he act of making an audio or audiovisual recording is necessarily included within the First Amendment’s guarantee of speech and press rights as a corollary of the right to disseminate the resulting recording. The right to publish or broadcast an audio or audiovisual recording would be insecure, or largely ineffective, if the antecedent act of making the recording is wholly unprotected."[29][30] However, the legality of the auditors' actions beyond mere filming are frequently subject to debate. As long as the auditor remains in a public place where they are legally allowed to be, they have the right to record anything in plain view, subject to very limited time, place, and manner restrictions.[31][32]

Some auditors occasionally yell insults, derogatory language, and vulgarities at police officers who attempt to stop them from recording or improperly demand identification.[10] Police will sometimes charge auditors with disorderly conduct when they engage in behavior that could be considered unlawful, for example, an auditor in San Antonio was prosecuted and convicted of disorderly conduct after an audit.[33] After the trial, the Chief of Police for the City of San Antonio stated "[the verdict] puts a dagger in the heart of their First Amendment excuse for insulting police officers..."[34] The auditor intends to appeal the decision.[35] Despite the San Antonio Police Chief's statement, insulting the police is consistently treated as constitutionally protected speech.[36][37][38] In State of Washington v. Marc D. Montgomery, a 15-year-old successfully won an appeal overturning his convictions for disorderly conduct and possession of marijuana on the grounds of free speech. Montgomery was arrested after shouting obscenities, such as "fucking pigs, fucking pig ass hole" at two police officers passing in their patrol car. Citing Cohen v. California, the Court ruled that Montgomery's words could not be classified as fighting words, and restricting speech based merely on its offensiveness would result in a "substantial risk of suppressing ideas in the process."[39]

The rights exercised in a typical audit are Freedom of Speech in the First Amendment, Freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures in the Fourth Amendment, and the Right to Remain Silent in the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution.

Auditors attempt to exercise their First Amendment right to photograph and record in public while avoiding committing any crime. The reason for this stems from the Supreme Court's decision in Terry v. Ohio which held that it was not a violation of the Fourth Amendment to detain someone when the officer has reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime. Further, following the Supreme Court's decision in Hiibel v. Sixth Judicial District Court of Nevada, the Court held that in States that have stop and identify statutes, a person may be required to provide their name to an officer who has reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime.

The conflict with law enforcement officers generally arises because officers sometimes deem photography, in and of itself, "suspicious behavior" and use that as a reason to detain an Auditor and demand identification. Universally, Courts that have reviewed this specific issue have held that the fact that a person takes a photograph or makes an audio or video recording in a public place or in a place he or she has the right to be, does not constitute, in and of itself, a reasonable suspicion to detain the person, probable cause to arrest the person, or a sufficient justification to demand identification. Some states have even revised their penal code to reflect that issue.[40] Nonetheless, officers frequently illegally detain or arrest auditors for "suspicious behavior." [41][42]

One of the main problems that auditors face in subsequent lawsuits are the Supreme Court's decisions in Harlow v. Fitzgerald, and Anderson v. Creighton, which held that government officials, including officers, would be shielded from liability and damages as long as their conduct does not violate "clearly established statutory or constitutional rights".[43] Therefore, while a Fourth Amendment seizure claim might exist for an auditor who stood on a public sidewalk and took pictures of a police station only to be handcuffed and placed in the back of a patrol car, a First Amendment claim would be dismissed because although a violation occurred, it was not "clearly established."[44] Qualified immunity allows "all but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law" to escape liability for egregious and obvious violations of civil rights.[45] So far the 1st, 3rd,[46] 5th, 7th,[47] 9th,[48] and 11th[49] Circuits have held that recording the police in the course of their official duties is a clearly established right.

Controversy

Intimidation

Auditing is controversial in nature due to the confrontational tactics of auditors, which some may see as intimidation or harassment.[50] In addition, many public employees are not familiar with handling people walking around silently recording their interactions. While the conduct is generally legal, such activity may cause alarm. Some auditors cite independent research into relevant laws, pointing out that they are currently being recorded by cameras in the building, or by stating that there is no expectation of privacy in public. Possible reasons people may be concerned stems from the cultural influence of the September 11 attacks which lead to an increase in concerns and paranoia of security and terrorism.

Profanity

Audits are even more confrontational when auditors engage in verbal disputes with government employees. Some auditors may use profane language during the audit. Some may confuse obscenity for profanity, and while the latter is generally protected by the first amendment, the right to engage in a verbal dispute depends highly on the circumstances. While on public streets, parks, or sidewalks, the right to free speech is at its highest, as one is within a traditional public forum. However, in limited public forums, such as public buildings, meeting rooms, and other public lobbies, the right to free speech may be more limited.

Open carry

Particularly controversial practices by auditors in the United States have involved the carrying of firearms. While many states protect individuals rights to openly carry, police fatalities while on duty increased by 56% between 2013 and 2018.[51] The six deaths during the 2016 Dallas police shooting was the deadliest incident for U.S. law enforcement since 9/11,[52] and followed shootings in March 2009 and 2009 Lakewood shooting which saw a combined nine deaths. Auditors and open carry activists inevitably share similar constitutional views and some have accompanied police violence campaigners, as in the case of the Dallas shooting when 20 to 30 open-carry gun rights activists were involved in the 800-person protest, some wearing bulletproof vests and fatigues.[53] In Dallas it was reported that police found the violence of the minority made it more difficult for officers to distinguish between suspects and marchers.[53] In instances where auditors do not respond to police questions or assert their right to silence, it can be difficult for police to ascertain whether an activist has a grievance with the police (and may have violent intentions) or merely whether they are asserting their right to film and challenge authorities in public.[53] However open carry activists such as those involved in the Dallas protest have contested this confusion, stating at the time that it was "not that difficult to tell who the good guys and the bad guys are".[53]

Goal

One auditor stated goal of an audit is to "put yourself in places where you know chances are the cops are going to be called. Are they going to uphold the constitution, uphold the law . . . or break the law?"[54] Auditors state that they seek to educate the public that photography is not a crime, while publicizing cases where officers illegally stop what is perceived as illegal conduct.[55][56]

An auditor selects a public facility and then films the entire encounter with staff and customers alike. If no confrontation or attempt to stop the filming occurs, then the facility passes the audit;[57] if an employee attempts to stop a filming event, it fails the audit.[58]

Some auditors are concerned that if officers are willing to harass, detain, and arrest auditors, who intentionally avoid doing anything that might be considered a crime, normal citizens might shy away from recording officers for fear of retaliation.[59][60] Justice Jacques Wiener of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit wrote in a 2017 federal appeals decision in favor of an auditor detained for filming police officers, “Filming the police contributes to the public’s ability to hold the police accountable, ensure that police officers are not abusing their power, and make informed decisions about police policy.”[6]

References

- "Photographers - What To Do If You Are Stopped Or Detained For Taking Photographs". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "First Amendment Audits and How to Respond • California Association of Labor Relations Officers". California Association of Labor Relations Officers. 2017-08-24. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- ""First Amendment Audits" Coming to Your Town?". CIRSA. 2018-06-18. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "First Amendment videotaped audit of police leads to investigation". WS Chronicle. 2015-03-26. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "Courting arrest for online clicks and the First Amendment - ExpressNews.com". expressnews.com. 2018-07-10. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- "What is 'auditing,' and why did a YouTuber get shot for doing it?". Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- "They roam public buildings, making videos. Terrorism experts say they may be dangerous". kansascity. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- Cushing, Tim (August 5, 2014). "Documents Show 100 Officers From 28 Law Enforcement Agencies Accessed A Photographer's Records". Techdirt. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- "Alabama Cop Snatches Camera from Man Recording Police Station". Photography is Not a Crime. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- Sommer, Will (2019-01-24). "The Insane New Path to YouTube Fame: Taunt Cops and Film It". Retrieved 2019-03-11.

- ""First Amendment auditor" claims sheriff deputy attacked him at Lebanon County courthouse - witf.org". witf.org. 2018-04-10.

- "Viral video of Ohio police causes outrage, crashes phone line". WKBN. 14 March 2018.

- Heinz, Frank. "Man Recording Police Files Complaint After Officer Draws Gun". NBC 5 Dallas-Fort Worth.

- Panzar, Javier; Reyes-Velarde, Alejandra; Queally, James (15 February 2019). "YouTube personality 'Furry Potato' shot and wounded outside L.A. synagogue". latimes.com. Retrieved 2019-02-17.

- "How a team of YouTubers went to war with a Texas police chief". The Daily Dot. 2018-12-31. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- Roberts, Michael (2019-02-05). "See Boulder Jail Cops Bust Men for Taking Video on Public Sidewalk". Westword. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- "First Amendment Audits and How to Respond • California Association of Labor Relations Officers". 24 August 2017.

- "You're on camera: How police should respond to a 'First Amendment audit'". PoliceOne.

- "PROP Instructor's Guide" (PDF). theiacp.org. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- "uk police audit - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- "Google Trends". Google Trends. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- "Earl David Worden: Another Case of Videographers vs. the Police". Mimesis Law. 2017-02-21. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "WATCH: PINAC Correspondent Arrested for not repeating his name". Photography is Not a Crime. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- P and P News (2018-08-13), 1st Amendment Audit Compilation 3, retrieved 2019-02-19

- "What Is 'Auditing,' And Why Did A YouTuber Get Shot For Doing It?". NDTV.com. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- WILLIAMS, SCOTT E. "GPD sergeant indicted in videographer's arrest". The Daily News. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "It didn't have to be this way - The Wetumpka Herald". The Wetumpka Herald. 2016-06-12. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "Glik v. Cunniffe". ACLU Massachusetts. 2015-06-21. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- https://cases.justia.com/federal/appellate-courts/ca7/11-1286/11-1286-2012-05-08.pdf?ts=1411041480

- "ACLU v. Alvarez". ACLU of Illinois. 2011-01-05. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "Public Recording of Police Activities; Instructor's Guide" (PDF). International Association of Chiefs of Police. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- "There Is a Constitutional Right of the Public to Film the Official Activities of Police Officers in a Public Place". Reason.com. 2017-12-17. Retrieved 2019-06-20.

- "City of San Antonio Successfully Prosecutes Individual for Disrupting Police Officers during Course of Duty". The City of San Antonio - Official City Website. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

"[R]epeated verbal attacks against us simply for wearing a uniform and performing our duties does not represent the spirit of the law,” San Antonio Police Chief William McManus

- Ramirez, Quixem (2019-03-06). "McManus: YouTubers confronting officers use first amendment as 'guise' to attack police". KTXS. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

- Caltabiano, David (2019-03-10). "Local YouTuber speaks out after conviction". WOAI. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

- Denvir, Daniel. "Everyone Has the Right to Mouth Off to Cops". CityLab. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

- "Court: First Amendment protects profanity against police". The Seattle Times. 2015-06-25. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

- "Can You Be Arrested for Cursing at the Police?". The Reeves Law Group. 2017-11-25. Retrieved 2019-03-11.

- "31 Wn. App. 745, STATE v. MONTGOMERY". courts.mrsc.org. Retrieved 2019-03-12.

- "Can you be arrested in California for refusing to provide ID to police when detained?". 2014-09-19.

- FERGUSON, JOHN WAYNE. "First Amendment activist arrested outside police station". The Daily News. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- "Video: Man Accuses Cranston Police Of Illegal Detention". Cranston, RI Patch. 2018-09-07. Retrieved 2019-02-16.

- "CONSTITUTIONAL LAW: To be "Clearly Established" or Not "Clearly Established": That is the Question".

- "Federal Appeals Court Sides with PINAC Reporter". Photography is Not a Crime. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "Qualified Immunity: Explained". The Appeal. Retrieved 2019-06-20.

- "Fields v. City of Philadelphia | ACLU of Pennsylvania". aclupa.org. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "Am. Civil Liberties Union of IL v. Alvarez, No. 11-1286 (7th Cir. 2012)". Justia Law. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "FindLaw's United States Ninth Circuit case and opinions". Findlaw. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "FindLaw's United States Eleventh Circuit case and opinions". Findlaw. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- Thomas, Judy L. "'First Amendment auditors' roam public buildings, making videos and raising fear". Journal Star. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- McCarthy, Niall. "The Number Of U.S. Police Officers Killed In The Line Of Duty Increased Last Year [Infographic]". Forbes. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- Park, Madison. "Dallas shooting is deadliest attack for police officers since 9/11". CNN. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- Fernandez, Manny; Blinder, Alan; Montgomery, David (2016-07-10). "Texas Open-Carry Laws Blurred Lines Between Suspects and Marchers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- Mikelionis, Lukas (2019-02-16). "Online activists' 'First Amendment audits' -- patriotism or provocation?". Fox News. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "Blind Justice escorted out of meeting by police in latest free speech test". 2019-02-05.

- "Lawmaker Who Pushed Bill to Protect People Filming Police Arrested for Filming Police". 2016-09-30.

- Peterson, Stephen. "Online group gives Foxboro Police Dept. high marks on preserving First Amendment rights". The Sun Chronicle. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- "Candid Cameras: How to Respond to a First Amendment Audit". Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. 2019-01-09. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- "Five Citations: Retaliation by police officer?". Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- Davich, Jerry. "'Do NOT touch my camera': Gary arrest prompts columnist to ask, where is the line regarding video of on-duty cops?". Post-Tribune. Retrieved 2019-02-16.