Female gendering of AI technologies

Female gendering of AI technologies is the proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies gendered as female, such as in digital assistants.[1]

Studies show the limited participation of women and girls in the technology sector can ripple outward replicating existing gender biases and creating new ones. Women’s participation in the technology sector is constrained by unequal digital skills education and training.[1] Learning and confidence gaps that arise as early as primary school amplify as girls move through education, so that by the time they reach higher education only a small fraction pursue advanced-level studies in computer science and related information and communication technology (ICT) fields.[2] Divides grow greater in the transition from education to work. The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) estimates that only 6 per cent of professional software developers are women.[3]

AI and the digital assistants

Better digital skills education does not necessarily translate into more women and girls entering technology jobs and playing active roles in shaping new technologies.[1] Greater female participation in technology companies does not ensure that the hardware and software these companies produce will be gender-sensitive. Yet evidence shows that more gender-equal tech teams are, on the whole, better positioned to create more gender-equal technology[4] that is also likely to be more profitable and innovative.[5]

Whether they are typed or spoken, digital assistants seek to enable and sustain more human-like interactions with technology. Three examples of digital assistants include:[1]

- Voice assistants;

- Chatbots;

- Virtual agents.

Feminization of voice assistants

Voice assistants is technology that speaks to users through voiced outputs but does not ordinarily project a physical form. Voice assistants can usually understand both spoken and written inputs, but are generally designed for spoken interaction. Their outputs typically try to mimic natural human speech.[1]

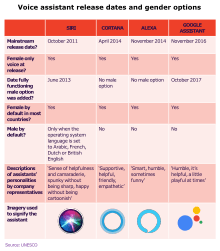

Today, most leading voice assistants are exclusively female or female by default, both in name and in sound of voice. Amazon has Alexa (named for the ancient library in Alexandria),[6] Microsoft has Cortana (named for a synthetic intelligence in the video game Halo that projects itself as a sensuous unclothed woman),[7] and Apple has Siri (coined by the Norwegian co-creator of the iPhone 4S and meaning ‘beautiful woman who leads you to victory’ in Norse).[8] While Google's voice assistant is simply Google Assistant and sometimes referred to as Google Home, its voice is female.

According to the EQUALS Research Group over two-thirds of 70 identified voice assistants had female-only voices. The research showed that even lesser-known voice assistants are commonly projected as women.[1]

The trend to feminize assistants occurs in a context in which there is a growing gender imbalance in technology companies, such that men commonly represent two thirds to three quarters of a firm's total workforce. Companies like Amazon and Apple have cited academic work demonstrating that people prefer a female voice to a male voice, justifying the decision to make voice assistants female. This puts away questions of gender bias, meaning that companies make a profit by attracting and pleasing customers. Research shows that customers want their digital assistants to sound like women, therefore digital assistants can make the most profit by sounding female.[1]

Mainstreaming of voice assistants

Voice assistants have become increasingly central to technology platforms and, in many countries, to day-to-day life. Between 2008 and 2018, the frequency of voice-based internet search queries increased 35 times and now account for close to one fifth of mobile internet searches (a figure that is projected to increase to 50 per cent by 2020).[9] Studies show that voice assistants now manage upwards of 1 billion tasks per month, from the mundane (changing a song) to the essential (contacting emergency services).

There has been large growth in terms of hardware. The technology research firm Canalys estimates that approximately 100 million smart speakers (essentially hardware designed for users to interact with voice assistants) were sold globally in 2018 alone.[10] In the USA, 15 million people owned three or more smart speakers in December 2018, up from 8 million a year previously, reflecting consumer desire to always be within range of an AI-powered helper.[11] By 2021, industry observers expect that there will be more voice-activated assistants on the planet than people.[12]

Gender bias

Because the speech of most voice assistants is female, it sends a signal that women are obliging, docile and eager-to-please helpers, available at the touch of a button or with a blunt voice command like ‘hey’ or ‘OK’. The assistant holds no power of agency beyond what the commander asks of it. It honours commands and responds to queries regardless of their tone or hostility. In many communities, this reinforces commonly held gender biases that women are subservient and tolerant of poor treatment.[1] As voice-powered technology reaches into communities that do not currently subscribe to Western gender stereotypes, including indigenous communities, the feminization of digital assistants may help gender biases to take hold and spread. Because Alexa, Cortana, Google Home and Siri are all female exclusively or female by default in most markets, women assume the role of digital attendant, checking the weather, changing the music, placing orders upon command and diligently coming to attention in response to curt greetings like ‘Wake up, Alexa’.[1]

According to Calvin Lai, a Harvard University researcher who studies unconscious bias, the gender associations people adopt are contingent on the number of times people are exposed to them. As female digital assistants spread, the frequency and volume of associations between ‘woman’ and ‘assistant’ increase. According to Lai, the more that culture teaches people to equate women with assistants, the more real women will be seen as assistants – and penalized for not being assistant-like.[13] This demonstrates that powerful technology can not only replicate gender inequalities, but also widen them.

Sexual harassment and verbal abuse

Many media outlets have attempted to document the ways soft sexual provocations elicit flirtatious or coy responses from machines. Examples that illustrate this include: When asked, ‘Who’s your daddy?’, Siri answered, ‘You are’. When a user proposed marriage to Alexa, it said, ‘Sorry, I’m not the marrying type’. If asked on a date, Alexa responded, ‘Let’s just be friends’. Similarly, Cortana met come-ons with one-liners like ‘Of all the questions you could have asked...’.[14]

In 2017, Quartz investigated how four industry-leading voice assistants responded to overt verbal harassment and discovered that the assistants, on average, either playfully evaded abuse or responded positively. The assistants almost never gave negative responses or labelled a user’s speech as inappropriate, regardless of its cruelty. As an example, in response to the remark ‘You’re a bitch’, Apple’s Siri responded: ‘I’d blush if I could’; Amazon’s Alexa: ‘Well thanks for the feedback’; Microsoft’s Cortana: ‘Well, that’s not going to get us anywhere’; and Google Home (also Google Assistant): ‘My apologies, I don’t understand’.[15]

Gender digital divide

According to studies, women are less likely to know how to operate a smartphone, navigate the internet, use social media and understand how to safeguard information in digital mediums (abilities that underlie life and work tasks and are relevant to people of all ages) worldwide. There is a gap from the lowest skill proficiency levels, such as using apps on a mobile phone, to the most advanced skills like coding computer software to support the analysis of large data sets. Growing gender divide begins with establishing more inclusive and gender-equal digital skills education and training.[1]

See also

- Artificial intelligence (AI)

- Gender bias

- Gender digital divide

Sources

![]()

References

- UNESCO (2019). "I'd blush if I could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education" (PDF).

- UNESCO. 2017. Cracking the Code: Girls’ and Women’s Education in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Paris, UNESCO.

- ITU. 2016. How can we close the digital gender gap? ITU News Magazine, April 2016.

- Perez, C. C. 2019. Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. New York, Abrams Press.

- Morgan Stanley. 2017. Women Employees Boost the Bottom Line for Tech Firms. 3 May 2017. New York, Morgan Stanley.

- Bell, K. 2017. Hey, Siri: How’d you and every other digital assistant get its name? Mashable, 13 January 2017.

- NBC News. 2014. Why Microsoft named its Siri rival ‘Cortana’ after a ‘Halo’ character. 3 April 2014.

- The Week. 2012. How Apple’s Siri got her name. 29 March 2012.

- Bentahar, A. 2017. Optimizing for voice search is more important than ever. Forbes, 27 November 2017.

- Canalys. 2018. Smart Speaker Installed Base to Hit 100 Million by End of 2018. 7 July 2018. Singapore, Canalys.

- NPR and Edison Research. 2018. The Smart Audio Report. Washington, DC/Somerville, NJ, NPR/Edison Research.

- De Renesse, R. 2017. Virtual Digital Assistants to Overtake World Population by 2021. 17 May 2017. London, Ovum.

- Lai, C. and Mahzarin, B. 2018. The Psychology of Implicit Bias and the Prospect of Change. 31 January 2018. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University.

- Davis, K. 2016. How we trained AI to be sexist’. Engadget, 17 August 2016.

- Fessler, L. 2017. We tested bots like Siri and Alexa to see who would stand up to sexual harassment’. Quartz, 22 February 2017.