Fanny Adams

Fanny Adams (30 April 1859 – 24 August 1867) was an English girl who was murdered by solicitor's clerk Frederick Baker in Alton, Hampshire, on 24 August 1867. The murder itself was extraordinarily brutal and caused a national outcry in the United Kingdom. Fanny was abducted by Baker and taken into a hop garden near her home. She was then brutally murdered and her body cut into several pieces, with some parts never being found. Further investigations suggested that two small knives were used for the murder, but it was later ruled they would have been insufficient to carry out the crime and that another weapon must have been used.

Used to express total downtime or inaction, the military, manual-trade and locker room talk phrase "sweet Fanny Adams" has been in use since at least the mid 20th century, vying with a stronger expletive.[n 1] Unusually, the phrase is not a bowdlerisation; "Fanny Adams" arrived in 1860s naval slang to deplore unliked meat stews. It broadened to mean anything badly substandard then further so as to merge with the expletive sharing its initial letters to mean nothing at all. The phrase also appears today as "sweet F.A."

Background

Fanny Adams (born 30 April 1859) and her family lived in Tanhouse Lane,[lower-alpha 1] on the northern side of Alton, a market town in Hampshire.[2][3] The 1861 census shows that Fanny lived with her father and five siblings. The family were apparently locally rooted; a George Adams and his wife Ann, believed to have been Fanny's grandparents, lived next door.[1][n 2]

Fanny was described as being a "tall, comely and intelligent girl". She appeared older than her real age of eight and was known locally for her lively and cheerful disposition. Fanny's best friend, Minnie Warner, was the same age and lived next door but one in Tanhouse Lane.[5] The town of Alton was renowned for its plentiful supply of hops, which led to many breweries opening in the town and made hop picking an integral part of its economy until the mid 20th century.[6] To the northern end of Tanhouse Lane lies Flood Meadows and surrounding the River Wey,[3] which sometimes flooded the area in times of heavy rain.[1] A large hop garden was located next to the meadows.[5]

Murder

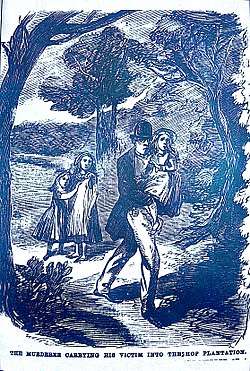

The small market town of Alton had previously seen little crime during the 19th century. The afternoon of 24 August 1867 was reported as fine, sunny and hot. It was around this time that Fanny, along with her sister Lizzie and best friend Minnie Warner, asked Harriet Adams if she could go out to the nearby Flood Meadows. Having no objections and being pleased for the girls to leave her while she was getting on with housework, Harriet agreed. Fanny and the local children had often played in Flood Meadows, owing to its close proximity to Tanhouse Lane and the fact that there had been no real crime in Alton within living memory.[5] As the girls were walking towards Flood Meadows and into a hop garden they met Frederick Baker, a 24-year-old solicitor's clerk. He was wearing a frock coat, light-coloured trousers and a tall hat on his head. Baker had moved to work and live in Alton about two months prior, which allegedly made him unfamiliar with the town.[7]

Baker gave Minnie and Lizzie three halfpence to spend on sweets and Fanny another halfpenny. The girls had seen Baker before at church meetings and were thus unconcerned about taking money from him. Baker then watched the girls run up and down The Hollow (a lane leading to the nearby village of Shalden) as they played and ate the blackberries he had picked for them.[7] An hour later, Lizzie and Minnie decided that they had had enough and opted to go home. Baker then approached Fanny and asked her to accompany him to Shalden. Fanny refused, and it was then Baker picked her up and carried her into the nearby hop garden.[7]

Lizzie and Minnie ran back to Tanhouse Lane and went straight to Martha Warner, who ignored them and so the girls carried on playing together, oblivious of Fanny's abduction. It was not until 5 pm that they made their way home for dinner. Mrs Gardner, who also lived in Tanhouse Lane, noticed Fanny's absence and asked the girls her whereabouts. The children relayed what had occurred earlier in the day and told Mrs Gardner that Fanny had accompanied the man. Mrs Gardner then relayed the information to Fanny's mother and the two set off to search for her.[8] They met with Baker after going only a short distance, near a gate separating the hop garden from Flood Meadows. According to the Hampshire Chronicle, Mrs Gardner asked Baker what he had done with the child. But Baker assured her that he often gave money to children for buying sweets. Mrs Gardner replied "I have a great mind to give you in charge of the police", to which Baker told her she could do what she liked. Baker's position in town as the solicitor's clerk initially deflected any suspicions the two women had. Both returned to their homes believing Fanny was still playing in one of the surrounding fields.[9]

Discovery

Sometime between 7:00 and 8:00 pm, Fanny had still not returned home, prompting Harriet Adams and a group of neighbours to search for her missing child. As the evening was setting the group began the search in The Hollow, to no success. In the nearby hop garden, however, labourer Thomas Gates (a Crimean War veteran who partook in the famous Charge of the Light Brigade[10]) found the head of Fanny Adams stuck on two hop poles while he was tending to the crops. An ear had been severed from the head which had two large cuts, from mouth to ear across the temple.[9] Further investigation discovered the remains of the child; the head, arms and legs were separated from the trunk. There were three incisions on the left side of the chest, and a deep cut on the left arm, dividing her muscles. Fanny's forearm was cut off at the elbow joint, and her left leg nearly severed off at the hip joint with her left foot cut off at the ankle point. Her right leg was torn from the trunk, and the whole contents of her pelvis and chest completely removed. Five further incisions had been made on the liver, the heart cut out, and vagina missing. Both of her eyes were cut out and found in the nearby River Wey.[11]

Distressed, Harriet Adams rushed to her husband who was playing cricket at the time to tell him of the news, however she collapsed before she reached him and word was sent instead.[12][13] When George Adams was told the details he returned home to take his loaded shotgun and set out to look for the culprit, but neighbours stopped him and instead sat with him through the night. The next day hundreds of people visited the hop garden to collect Fanny's scattered remains. The police tried unsuccessfully to find the murder weapons, as they suspected that small knives were used to commit the crime. It is likely that the crowd of searching people had inadvertently trampled down any clues left on the ground. Members of the crowd did, however, recover all of her cut clothes scattered around the field, with the exception of her hat.[12]

Most of her body parts were collected on that day but an arm, foot, and intestines were not found until the next morning. One foot was still in a shoe and the breast bone was never found. The remains of Fanny were collected together by searchers and taken to a house named Leathern Bottle to be sewn together, only yards away from her home. From there the police took them to the local police station. A stone which still had flesh and hair sticking to it was handed in to the police as evidence, as they thought it may have been the actual murder weapon.[14]

Arrest of Frederick Baker

That evening police superintendent William Cheyney hurried from the local police station to Flood Meadows, where he was met by several people who then led him to the Leathern Bottle. Upon arrival the proprietor of the house handed Cheyney a bundle labelled "portions of a child", and with the help of some of his officers, organised a search to trace the missing body parts.[15] Hearing that Frederick Baker had been seen with the children prior to Fanny's disappearance, Cheyney retraced his steps through the town and located his place of work. Arriving at the solicitor's office at 9 pm, he found Baker still at work although he usually left an hour before. Baker protested innocence despite being informed that he was the only suspect. After making further enquiries around town, Cheyney had no alternative but to arrest Baker on suspicion of murder. By this time a large and agitated crowd had gathered outside the solicitor's offices, forcing the police to smuggle Baker out of the back door for fears that people would kill him.[15]

When searched at the police station, Baker was found to be in the possession of two unstained small knives. Spots of blood were observed on both wristbands of his shirt, and his trousers had been soaked to conceal the bloodstains. After being questioned about his appearance, Baker responded: "Well, I don't see a scratch or cut on my hands to account for the blood".[15] Baker's conduct during his interrogation was described as cool and collected. Some time after the arrest, Cheyney backtracked to Baker's desk in the solicitor's office and discovered a diary among some legal papers. An entry had been made for Saturday 24 August 1867 which recorded: "Killed a young girl. It was fine and hot".[16] The Hampshire Chronicle reported that the hop garden had been cleared on 21 September, but nothing connected with the murder had been found. It also added that Baker remained completely unfazed with the murder and did not exhibit any symptoms of insanity. Further confusion was added when Baker retorted that he was intoxicated after seeing the children, but all evidence and witnesses reject his claim.[16] Baker was transferred to Winchester Prison on 19 October.[17]

Investigation

Following investigations from Hampshire Constabulary continued until October. It was around this time when a young boy whose parents lived close to the Adams family came forward as an eyewitness. The boy testified that he saw Baker emerge from the hop garden at about 2 pm on the day Fanny was murdered, with his hands and clothes saturated with blood. Baker was then to have reportedly stooped down to the river and calmly wipe himself with a handkerchief, after which he put a small knife and another unidentified weapon in his jacket pockets. The boy had related this story to his mother at the time but she had not told anyone until she spoke out in a pub two months later.[18] The police searched the whole area for sixteen days but no other weapons were found.[16]

Superintendent Cheyney requested an immediate forensic test in late October. All recovered clothes and the two knives were taken from Baker and sent to Professor A.S. Taylor at Guy's Hospital in London, where they received the most detailed tests possible at the time.[19] After examining them over the coming weeks, Taylor was able to confirm that the blood on the knives was from a human. One of the small knives contained a small amount of coagulated blood although none was on the handle. Under cross-examination Taylor stated he would have expected more blood on the knives and signs of rust if they had been washed, but the quantity of blood found was surprisingly small. However, Taylor opined that an inexperienced person armed with a proper weapon could dismember a body in about half an hour — blood would still run but would not have spurted from the body.[20] Further examination of Baker's clothes uncovered some small experiences of diluted blood in some parts of his waistcoat, trousers and stockings. The wristbands of his shirt had been folded back and diluted blood stained the folds. There was no sign of sexual intercourse with the body.[20]

Doctor Lewis Leslie from Alton thought the ultimate cause of death was probably by a blow to the head with a stone. Leslie speculated that a larger instrument had to have been used to cut the body, and also added that dismemberment was achieved in less than an hour. Forensics indicated that cuts had been made when the body was still warm, and that Fanny had not only been cut but also hacked and torn to pieces. The time it had taken Baker to cut the body into so many pieces most likely gave him the opportunity to choose his positioning so that he might not necessarily be covered in blood. The forensic staff in London concluded that the small knives found in Baker's possession would not have been capable of severing Fanny's body, so another weapon had to have been used.[21]

Meanwhile, in Winchester Prison, Baker was said to be talkative to the wardens and especially the chaplain. He still insisted that his conscience was clear as to the murder and wondered who the guilty party was, hoping that "he would be found". He ate and slept well which was in contrast to his time in Alton's prison, where he was reportedly disturbed in his sleep and physically shuddered at the sight of meat.[17]

Trial

Initial trials in Alton

British law at the time required that in the case of sudden death an immediate inquest must be held under the jurisdiction of a coroner. In the case of Fanny Adams' inquest, Deputy County Coroner Robert Harfield was in charge of the proceedings which were held at the Dukes Head Inn in Alton on 27 August 1867. Alton's divisional police superintendent William Cheyney was in attendance along with acting Chief Constable superintendent Everitt, who was representing Hampshire Constabulary.[22] Coincidentally, the pub where the initial trials were held was opposite the solicitor's offices where Baker worked and very close to the police station.[23]

The first to give evidence was Minnie Warner. She told the jury that Fredrick Baker gave her money to run down The Hollow with Fanny and into a nearby field while Baker picked blackberries for them. She was unable to identify Baker but correctly described what he was wearing when he murdered Fanny.[22] The next to testify was Fanny's mother, Harriet. She recalled that she met Baker at the gate to the hop garden, and that he was headed towards the road which led to Basingstoke. It was there Minnie identified Baker as the man who gave her the pennies. Baker contradicted Minnie at the time by saying "no, three halfpence". When asked by Harriet to give his name, Baker refused but told her where he could be found.[24]

Mrs Gardner, who had accompanied Harriet Adams to search for the missing girl, gave evidence next. She was able to identify Baker and told the jury that he appeared to be very relaxed at the time she saw him. After asking him if he had seen the missing child and enquiring why he had given her money, Mrs Gardner told Harriet that she should "give him in charge to the police", to which Baker calmly responded: "the reason why I speak so is that an old gentlemen has been giving halfpence to the children for no good purpose, and I thought you were of the same sort". After being asked again of Fanny's whereabouts, Baker said that he left her at the gate to play. The coroner asked Baker if he wanted to cross-question the witness, but he declined.[24]

At his trial on 5 December, the defence contested Minnie Warner's identification of Baker and claimed the knives found were too small for the crime anyway. They also argued insanity: Baker's father had been violent, a cousin had been in asylums, his sister had died of a brain fever and he himself had attempted suicide after a love affair. The defence also argued that the diary entry was typical of the "epileptic or formal way of entry" that the defendant used and that the absence of a comma after the word killed did not render the entry a confession.[25]

Justice Mellor invited the jury to consider a verdict of not responsible by reason of insanity, but they returned a guilty verdict after just fifteen minutes. On 24 December, Christmas Eve, Baker was hanged outside Winchester Gaol. The crime had become notorious and a crowd of 5,000 attended the execution. This was the last public execution held at that gaol.[26] Before his death, Baker wrote to the Adamses expressing his sorrow for what he had done "in an unguarded hour" and seeking their forgiveness.

Fanny was buried in Alton cemetery. The headstone, erected by voluntary subscription, reads:

Sacred to the memory of Fanny Adams aged 8 years and 4 months who was cruelly murdered on Saturday August 24th 1867. Fear not them which kill the body but are not able to kill the soul but rather fear Him which is able to destroy both body and soul in hell. Matthew 10 v 28.

Legacy

In 1869 new rations of tinned mutton were introduced for British seamen. They were unimpressed by it, and suggested it might be the butchered remains of Fanny Adams. "Fanny Adams" became slang for mediocre mutton,[27] stew, scarce leftovers and then anything worthless. The large tins the mutton was delivered in doubled as mess tins. These or cooking pots are still known as Fannys.

By the mid-20th century, many working class men were pretending to their sons and social superiors that their own favored expression, "sweet F.A.", stood for "sweet Fanny Adams" with its commonplace meaning of total inaction or downtime, while they and their peers used that expression among themselves to mean "sweet fuck all". Sweet Fanny Adams has lingered as a euphemism for that expletive. "Scotch mist" has long been the more general slang for nothing at all and as nothing pejorative.

Notes and references

- References

- Cansfield 2004, p. 11.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 9.

- "Flood Meadows and the surrounding area". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 16-17.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 17.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 12.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 18.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 18-19.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 20.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 88.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 21.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 23.

- Anon. "The true story of sweet Fanny Adams". Hantsweb: Curtis museum. Hampshire County Council. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 22.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 33.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 35.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 37.

- Cansfield 2004, pp. 35-36.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 36.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 60.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 61.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 39.

- "Dukes Head and the surrounding area". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- Cansfield 2004, p. 40.

- "The Alton Murder". Police News Edition of the trial and condemnation of Frederick Baker. Illustrated police news office, 275 Strand, London. 1867. p. 10. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- "Weeke local History - Winchester Prison". www.weekehistory.co.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- Sweet Fanny Adams

- Notes

- That of the same time origin, incorporating "fuck all"

- George Adams junior, originally a labourer married Harriet Mills in 1850 who had Ellen (born 1852), followed by two sons, George (born 1853), Walter (1856), Fanny in 1859, baptised on 31 July then Elizabeth (known as Lizzie) in 1862, Lily Ada in 1866 and Minnie in 1871.[4]

- Bibliography

- Cansfield, Peter (2004). The True Story of Fanny Adams (Second ed.). Soldridge: Peter Cansfield Associates. pp. 5–106. ISBN 978-0953634613.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Notes

- Tanhouse Lane itself is only 400 yards (370 m) long.[1]

References

- "Killed a Young Girl. It was Fine and Hot: The Murder of Sweet FA" : Author - Keith McCloskey: available on Amazon : published 2016 ISBN 978-1534634312

- Fanny Adams page at the Curtis Museum in Alton

- Why Do We Say ...?, Nigel Rees, 1987, ISBN 0-7137-1944-3.

External links

| Look up Fanny Adams or sweet FA in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Execution of Frederick Baker, the Alton Murderer, ballad in Curiosities of Street Literature by Charles Hindley (London 1871), at the University of Virginia Library

- Execution of Frederick Baker, song at the Digital Tradition Mirror

- Fanny Adams - Children Who Never Made It Home

- Fanny Adams at Find a Grave