Facultad de Derecho Eugenio Maria de Hostos

The Facultad de Derecho Eugenio Maria de Hostos (English: Eugenio María de Hostos School of Law) was a law school located in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico. The School was founded by Fernando Bayrón, Juan Mari Brás and Carlos Rivera Lugo in 1995.[1] The institution lost its ABA accreditation, and then the Puerto Rico Supreme Court also withdrew the accreditation due to school's economical difficulties. Hostos has been closed since 2013, when the last commencement ceremony had only eight graduates. The Eugenio Maria de Hostos Law School (or, Hostos Law School, for short) aspired to achieve the development of a legal professional also responsive to the needs of his or her communities and who would embraced the Hostos educational philosophy.[2]

Facultad de Derecho Eugenio María de Hostos | |

Other name | Hostos Law School FDEMDH |

|---|---|

| Motto | Una institución de Compromiso Social (English: "An institution of Social Commitment") |

| Named After | Eugenio María de Hostos |

| Founders | Fernando Bayrón Toro Juan Mari Brás Carlos Rivera Lugo |

| Type | Private |

| Active | 1995–2013 |

Parent institution | Fundación Facultad de Derecho Eugenio María de Hostos (English: "Eugenio María de Hostos Law School Foundation") |

| Dean | Carlos Rodríguez Sierra (2004-2014) Roberto Vélez Colón (2004) Carlos Rivera Lugo (1993-2003) |

| Address | 57 South Peral Street – Corner Muñoz Rivera St. PO Box 1900 , Mayagüez , Puerto Rico , 00681-1900 |

| Campus | Urban |

| Language | Spanish |

| Website | Official Website (Defunct) |

History

Accreditation

On 28 October 1996, the parent institution of the School, the Eugenio María de Hostos Law School Foundation (FFDEMH, for its initials in Spanish), requested an accreditation extension from the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico. A committee for such a purpose was named by the Court in 20 December. The committee submitted its final report which did not recommend accreditation, on 11 July of the following year. Two observations made by the committee were that the institution lacked the financial means to operate and the academic profiles of its students were subpar compared to other law schools in Puerto Rico.[3]

The American Bar Association (ABA) denied the school's request for a provisional accreditation on 15 July 1997. This was detrimental, since Puerto Rican law requires that to be accepted into the Bar, all persons must have graduated from an ABA-accredited institution. As such, on 13 August, the Supreme Court released a resolution refusing entry into the bar to the first cohorts of graduates. However, the Supreme Court also resolved that these graduates were able to take the bar examination on September 1997, to obtain data from the test results. Only 36% of the class passed the examination, compared to 79% of the University of Puerto Rico School of Law, 63% from the Interamerican University, and 61% of the Pontificial Catholic University of Puerto Rico School of Law graduates on their first attempt.[4]

Consequentially, the Supreme Court released a second resolution were they established their worry that the Hostos Law School lacked the "budgetary soundness", had difficulties in recluting students who were able to pass the bar examination post-graduation, as well as not having obtained the provisional accreditation from ABA.[5] The Supreme Court, on a 4-2 vote on the resolution, gave a second opportunity to Hostos, having been persuaded by a promise from the insitution that there would be "significant improvement" on the bar examination results between 1998-1999 "if [the Supreme Court] gave said graduates the opportunity of taking the bar examination." If Hostos delivered on their promise, as well as obtaining at least one provisional accreditation from ABA, in two years time, then the Supreme Court would grant the requested accreditation. If said requirements were not satifised the Supreme Court would refuse the accreditation request and not accept any graduates for the bar examination from 2000 on. Additionally, the Supreme Court requested that all enrolled students and all students admitted from 1 April 1998 be individually notified of the Court's second resolution and its implications for the Hostos Law School.[6]

The Hostos' Application Provisional Accreditation Committee of the American Bar Association visited the institution between March 7-10, 1999.[7]

| Name | Institution |

|---|---|

| Dean Leigh H. Taylor (Chair) | Southwestern University School of Law

Los Angeles, California |

| Dean Donald J. Dunn | Western New England College School of Law

Springfield, Massachusetts |

| Prof. Martin Frey | University of Tulsa College of Law

Tulsa, Oklahoma |

| Prof. Edith Z. Friedler | Loyola Marymount University-Los Angeles

Los Angeles, California |

| Rufina A. Hernández | Latin American Research and Service Agency

Denver, Colorado |

| Erica Moeser, Esq. | National Conference of Bar Examiners

Madison, Wisconsin |

| Prof. Joyce Saltalamachia | New York Law School

New York, New York |

After the two years lapsed, the institution had not satisfied the two conditions, including having inferior bar examination rates compared to the other three accreditated law schools, as well as having been denied the provisional accreditation from ABA for a second time on 24 november 1999.[8]

| Law School | Sept '98 | Mar '99 | Sept '99 |

|---|---|---|---|

| UPR | 87% | 78% | 83% |

| UI | 52% | 46% | 48% |

| UC | 51% | 31% | 48% |

| EMH | 19% | 0% | 22% |

The Supreme Court denied the accreditation and stated that no graduates would be permitted to take the bar examinations from 2000 and on. However, those who had failed the tests from 1997 to 1999 were able to reattempt the bar examination. The Court argumented that "[a]fter seven years from having been founded... it is not justified that [the Court] continue making excpetions to...norms and regulations...that are required of any other applicant."[9] On a particular vote made by the Associate Justice Jaime Fuster Berlingeri mentioned that Hostos had an "irreparable medullar problem" in achiving its goals. He credited this to the incapacity of recluting capable students of passing the bar examination. Fuster Berlingeri added the results for the law school entrance exam, the Graduate Studies Admissions Test (PAEG, for Prueba de Admisión a Estudios Graduados). The Hostos Law School alleged that they "could not reclute better students for lack of accreditation." Fuster Berlingeri refuted this by suggesting that the most probable cause was the geographic location, where there were less students in the region for a fourth law school.[10] Out of all the passing marks of the bar exams offered in the month of September in the years 1997 to 1999, only 12% came from the 16 municipalities in the western region of Puerto Rico, which meant that even if the Hostos could reclute all students from it region, it would still be a small part of the general law school market. 54% of all Hostos graduates who took the bar exam were not from the region and 85% of these graduates also lacked the average PAEG score of those who did pass.[11] Even though the cost for three years attendace was at least $100,000, the institution had to resort to donations to keep itself afloat.[12]

| Year | All of PR | EMH | UPR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | 604 | 532 | 660 |

| 1998 | 593 | 504 | 657 |

| 1999 | 595 | 509 | 655 |

The Hostos Law School did not request a reconsideration from the Supreme Court.[14] On March 9 2000, the Court expanded the time window to students who had taken the bar exam on March 2000 to be admitted to the bar as well.[15]

2003 Provisional Accreditation

Hostos resubmitted a request for provisional accreditation in the Supreme Court on 13 December 2002.[16] The Court decided to name a Comittee of Accreditation, composed of:

- Jorge Pérez Díaz, Esq. (Chair)

- Dr. José R. González

- Rafael Martínez, CPA

- Dr. Efraín González Tejera

- José Sosa Llorens, Esq.

- James P. White (Counsel to the Committee)-former ABA consultant

The committee submitted its final report on 19 June 2003. On the 27 the Court, through a resolution, decided to grant Hostos a five-year provisional accreditation.[17] This was subject to the following conditions:

- Admissions-Hostos would have to maintain an admittance policy of a minimum of 500 on the PAEG and, from 2003-07, increase the rate of admitted students to 70% to those who have over the score of 550.[18]

- Administration and Financial Situation-required that by the end of the year 2003, Hostos name an Associate Dean of Finance and an Associate Dean of Academic and Student Affairs, as well as pay their overdue debts and implement realistic financial plans.[19]

- Faculty-by 30 June 2004, Hostos would have to adopt a professional development plan, whereby the faculty would be able to do their post-graduate studies and investigations in multiple universities.[20]

- Library-the Law School would have to acquire the necessary law collections and provide them for public use and submit a plan for a permanent library site at the side of the permanent building on Peral Street, since the library was lodged at a rented site on the José de Diego Street.[21]

- Bar exam results-from May 2006 on, the rate of graduates who passed the bar exam on their first attempt would not be less than 75% of the lowest score of any of the other three accredited law schools. For the classes of 2007 and '08, the rate would be 80% and 85%, respectively.[22]

- ABA Accreditation-By 31 June 2007, Hostos must have obtained either a provisional or permanent accreditation from the American Bar Association.[22]

- Progress Reports-the Board of Trustees would have to submit progress reports on all conditions every 31 of January and July every year from 2004 on.[23]

All students, at the time presently enrolled, or who enrolled in the future, would be handed a copy of these conditions as well as a Memorandum of Understanding between the Supreme Court and Hostos Law School. In addition, all graduates from December 2003 on would be able to take the bar examinations.[23] Finally, the resolution stated that Hostos had ninety days to submit a proposed plan to offer a course for all those who graduated from September 1999, when it lost its original accreditation, ableing them to take the bar exams.[24]

The final plan for the course, titled "Legislation and Jurisprudence Analysis Preparatory Program", for all those who did graduate when the institution was not accredited was referred to the Committee of Accreditation set up by the Court.[25] The program consisted of "an intensive study and discussion program of the 13 subjects that are the object of evaluation in the general law examination."[26] Since this cohort of students had below average PAEG scored and graduated from a non-accredited institution, the Court rquired, that after completing the preparatory course, graduates must be recertified by Hostos.[25] However, the Committee rejected the Hostos proposal that these students obtain at least 70% in the program as a condition for their re-certification.[25] The Court adopted all of the Committee's recommendations on 12 March 2004.[27]

Building

The permanent seat of the Eugenio Maria de Hostos School of Law located in the building formerly occupied and known as the Luis Muñoz Rivera elementary public school. It was built in 1924, when Juan Rullán Rivera was mayor of the city of Mayagüez.[28] The site was originally occupied by the Municipal Slaughterhouse during the early 19th century. For this reason the current street of the school, Georgina Morales, was known as "La Calle de la Carnicería" or slaughterhouse street. By 1848, the municipal prison building was built which gave its name to the Barrio where today the Eugenio María de Hostos School of Law was located.[28]

The building was designed by Rafael Carmoega, whose other works include the Capitol of Puerto Rico, the School of Tropical Medicine (Escuela de Medicina Tropical), the old Casino de Puerto Rico, and the first buildings of the University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras Campus.[28] The architectural style of the building is mostly modernist, with elegant, although reserved, neoclassical accents including its access facade that is a Doric order of columns.[28]

The public elementary school closed down in 1985. The remodeling design of the building was the work of Mayagüez architect Juan Manuel Moscoso. The property was restored and rehabilitated to house the law school by the Mayagüez Municipal Government during the years 1997 to 1999, under the mayoralty José Guillermo Rodríguez. The building was inaugurated as the permanent seat of the law school on May 7, 1999.[28]

Competition

Eugenio Maria de Hostos Law School students were winners of the 2011 Puerto Rico-wide Law School Students Competition Contest. The competition included students from all law schools in Puerto Rico, and measured legal knowledge matter.[29]

Financial Situation

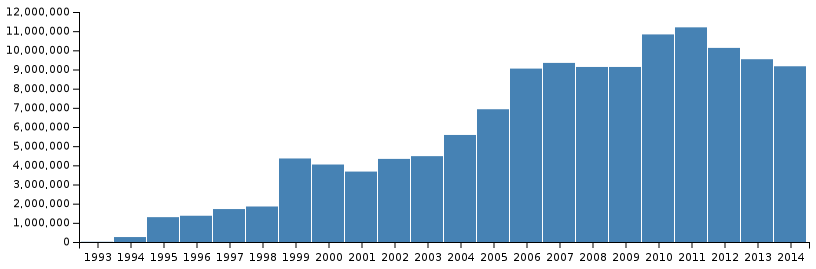

The Hostos Law School started off in 1993 with $12,144 of total assets, this reached an all-time high in 2011 of $11,199,337, a year after it got its accreditation rescinded by the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico.[30]

Notable Faculty

- Juan Mari Brás-founder.

Notable Alumni

- Eric Alfaro Calero-one-term Representative and last Commissioner of Municipal Affairs.

- José Luis Dalmau Santiago (JD '97)-five term Senator.

Notes

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-02-10. Retrieved 2009-12-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-02-10. Retrieved 2009-12-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- 2000 TSPR 25, p. 2.

- 2000 TSPR 25, p. 3.

- 2000 TSPR 25, p. 3.

- 2000 TSPR 25, p. 4.

- "ABA Accreditation Law School Site Evaluations Visits 1998-1999". ABA Journal. 85: 110. 1999-12-01. Archived from the original on 2020-06-06.

- 2000 TSPR 25, p. 5.

- 2000 TSPR 25, p. 6.

- 2000 TSPR 25, p. 8.

- 2000 TSPR 25, pp. 9-10.

- 2000 TSPR 25, p. 11.

- 2000 TSPR 25, p. 8.

- 2000 TSPR 38, p. 7.

- 2000 TSPR 38, p. 2.

- 2003 TSPR 29, p. 2.

- 2003 TSPR 110, p. 2.

- 2003 TSPR 110, p. 3.

- 2003 TSPR 110, p. 3-4.

- 2003 TSPR 110, p. 4.

- 2003 TSPR 110, p. 4-5.

- 2003 TSPR 110, p. 5.

- 2003 TSPR 110, p. 6.

- 2003 TSPR 110, p. 7.

- 2004 TSPR 38, p. 5.

- 2004 TSPR 38, p. 4.

- 2004 TSPR 38, p. 1, 5.

- "Facultad de Derecho Eugenio María de Hostos" (in Spanish). Mayagüez sabe a mango. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- Estudiantes de derecho de la Eugenio María de Hostos ganan competencia. El Sur a la Vista. Ponce, Puerto Rico. 24 April 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- "Annual Fillings of the Fundación Escuela de Derecho Eugenio María de Hostos". Department of State Registry of Corporations and Entities. Archived from the original on 2020-06-06. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

References

- Supreme Court of Puerto Rico (2000-02-18). "Resolución del Tribunal Supremo 2000 TSPR 25" [Supreme Court Resolution 2000 TSPR 25] (PDF). Rama Judicial de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-06-06. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- Supreme Court of Puerto Rico (2000-03-09). "Resolución del Tribunal Supremo 2000 TSPR 38" [Supreme Court Resolution 2000 TSPR 38] (PDF). Rama Judicial de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-06-06. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- Supreme Court of Puerto Rico (2003-03-04). "Resolución del Tribunal Supremo 2003 TSPR 29" [Supreme Court Resolution 2003 TSPR 29] (PDF). Rama Judicial de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-06-07. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- Supreme Court of Puerto Rico (2003-06-27). "Resolución del Tribunal Supremo 2003 TSPR 110" [Supreme Court Resolution 2003 TSPR 110] (PDF). Rama Judicial de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-06-07. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- Supreme Court of Puerto Rico (2004-03-12). "Resolución del Tribunal Supremo 2004 TSPR 38" [Supreme Court Resolution 2004 TSPR 38] (PDF). Rama Judicial de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-06-07. Retrieved 2020-06-07.