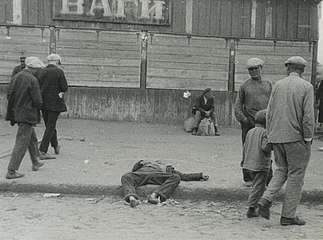

Excess mortality in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin

Estimates of the number of deaths attributable to the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin vary widely. Some scholars assert that record-keeping of the executions of political prisoners and ethnic minorities are neither reliable nor complete,[1] others contend that archival materials declassified in 1991 contain irrefutable data far superior to sources used prior to 1991, such as statements from emigres and other informants.[2][3]

Prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the archival revelations, some historians estimated that the numbers killed by Stalin's regime were 20 million or higher.[4][5][6] After the USSR dissolved, evidence from the Soviet archives was declassified and researchers were allowed to study it. This contained official records of 799,455 executions (1921–1953),[7] around 1.7 million deaths in the Gulag,[8][9] some 390,000[10] deaths during the dekulakization forced resettlement, and up to 400,000 deaths of persons deported during the 1940s[11] – with a total of about 3.3 million officially recorded victims in these categories.[12] The deaths of at least 5.5 to 6.5 million[13] persons in the famine of 1932–33 are sometimes, but not always,[2][14] included with the victims of the Stalin era.

Events

Gulag

According to official Soviet estimates, more than 14 million people passed through the Gulag from 1929 to 1953, with a further 7 to 8 million being deported and exiled to remote areas of the Soviet Union (including entire nationalities in several cases).[15]

According to a 1993 study of recently declassified archival Soviet data, a total of 1,053,829 people died in the Gulag (not including labor colonies) from 1934 to 1953 (there was no archival data for the period 1919–1934).[16]:1024 More recent archival figures for the deaths in the Gulag, Labor Colonies, and prisons combined for 1931–53 were 1.713 million.[14] However, taking into account the likelihood of unreliable record keeping, and the fact that it was common practice to release prisoners who were either suffering from incurable diseases or near death,[17][18] non-state estimates of the actual Gulag death toll are usually higher.

For example, Golfo Alexopoulos, history professor at the University of South Florida, believes that at least 6 million people died as a result of their detention in the gulags.[19] This estimate is disputed by other scholars; critics such as J. Hardy say that the evidence Alexopoulos used is indirect and misinterpreted,[20] and Dan Healey says that the estimate has obvious methodological difficulties.[21]

John G. Heidenrich, citing materials pre-1991, estimates the number of deaths at 12 million.[22] His book is not primarily about estimating deaths from repressive policies in the Soviet Union. He appears to have relied on Solzhenitsyn's political and literary work, The Gulag Archipelago, which Stephen Wheatcroft notes was not intended as a historical fact, but a challenge to Soviet authorities after their years of secrecy.[23]

According to estimates based on data from Soviet archives post-1991, there were around 1.6 million deaths during the whole period from 1929 to 1953.[24] The tentative historical consensus is that, of the 18 million people who passed through the gulag system from 1930 to 1953, between 1.5 and 1.7 million died as a result of their incarceration.[21]

Soviet famine of 1932–33

The deaths of 5.7 [25] to perhaps 7.0 million people [26][27] in the 1932–1933 famine and collectivization of agriculture are included among the victims of repression during the period of Stalin by some historians.[28][29] This categorization is controversial however, as historians differ as to whether the famine in Ukraine was created as a deliberate part of the campaign of repression against kulaks and others,[30][31][32][33][34] was an unintended consequence of the struggle over forced collectivization[35][36][37][38][39] or was primarily a result of natural factors.[40][41][42][43]

Judicial executions

According to official figures there were 777,975 judicial executions for political charges from 1929–53, including 681,692 in 1937-38, the years of the Great Purge[8] Unofficial estimates estimate a total number of Stalinism repression deaths in 1937–38 at 950,000–1,200,000.[44]

Soviet famine of 1946–47

The last major famine to hit the USSR began in July 1946, reached its peak in February–August 1947 and then quickly diminished in intensity, although there were still some famine deaths in 1948.[45] Economist Michael Ellman claims that the hands of the state could have fed all those who died of starvation. He argues that had the policies of the Soviet regime been different, there might have been no famine at all or a much smaller one. Ellman claims that the famine resulted in an estimated 1 to 1.5 million lives lost in addition to secondary population losses due to reduced fertility.[45]

Population transfer by the Soviet Union

Deportation of kulaks

Large numbers of kulaks regardless of their nationality were resettled to Siberia and Central Asia. According to data from Soviet archives, which were published in 1990, 1,803,392 people were sent to labor colonies and camps in 1930 and 1931, and 1,317,022 reached the destination. Deportations on a smaller scale continued after 1931. Data from the Soviet archives indicates 2.4 million Kulaks were deported from 1930–34.[46] The reported number of kulaks and their relatives who had died in labour colonies from 1932 to 1940 was 389,521.[10][47] Simon Sebag Montefiore estimated that 15 million kulaks and their families were deported by 1937, during the deportation many people died, but the full number is not known.[48]

Forced settlements in the Soviet Union 1939-53

According to the Russian historian Pavel Polian 5.870 million persons were deported to forced settlements from 1920–1952, including 3.125 million from 1939–52. [46] Those ethnic minorities considered a threat to Soviet security in 1939–52 were forcibly deported to Special Settlements run by the NKVD. Poles, Ukrainians from western regions, Soviet Germans, Balts, Estonians peoples from the Caucasus and Crimea were the primary victims of this policy. Data from the Soviet archives list 309,521 deaths in the Special Settlements from 1941–48 and 73,454 in 1949–50.[49] According to Polian these people were not allowed to return to their home regions until after the death of Stalin, the exception being Soviet Germans who were not allowed to return to the Volga region of the USSR.

Katyn massacre

The massacre was prompted by NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria's proposal to execute all captive members of the Polish officer corps, dated 5 March 1940, approved by the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, including its leader, Joseph Stalin. The number of victims is estimated at about 22,000.[50]

Total number of victims

In 2011, the historian Timothy D. Snyder, after assessing 20 years of historical research in Eastern European archives, asserts that Stalin deliberately killed about 6 million (rising to 9 million if foreseeable deaths arising from policies are taken into account).[51][52]

The release of previously secret reports from the Soviet archives in the 1990s indicate that the victims of repression in the Stalin era were about 9 million persons. Some historians claim that the death toll was around 20 million based on their own demographic analysis and from dated information published before the release of the reports from the Soviet archives.[60] American historian Richard Pipes noted: "Censuses revealed that between 1932 and 1939—that is, after collectivization but before World War II—the population decreased by 9 to 10 million people.[61] In his most recent edition of The Great Terror (2007), Robert Conquest states that while exact numbers may never be known with complete certainty, at least 15 million people were killed "by the whole range of Soviet regime's terrors".[62] Rudolph Rummel in 2006 said that the earlier higher victim total estimates are correct, although he includes those killed by the government of the Soviet Union in other Eastern European countries as well.[63][64] Conversely, J. Arch Getty, Stephen G. Wheatcroft and others insist that the opening of the Soviet archives has vindicated the lower estimates put forth by "revisionist" scholars.[65][66] Simon Sebag Montefiore in 2003 suggested that Stalin was ultimately responsible for the deaths of at least 20 million people.[67]

Some of these estimates rely in part on demographic losses. Conquest explained how he arrived at his estimate: "I suggest about eleven million by the beginning of 1937, and about three million over the period 1937–38, making fourteen million. The eleven-odd million is readily deduced from the undisputed population deficit shown in the suppressed census of January 1937, of fifteen to sixteen million, by making reasonable assumptions about how this was divided between birth deficit and deaths."[68]

Some historians also believe that the official archival figures of the categories that were recorded by Soviet authorities are unreliable and incomplete.[1] In addition to failures regarding comprehensive recordings, as one additional example, Canadian historian Robert Gellately and British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore argue that the many suspects beaten and tortured to death while in "investigative custody" were likely not to have been counted amongst the executed.[69][70] Conversely, Australian historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft asserts that prior to the opening of the archives for historical research, "our understanding of the scale and the nature of Soviet repression has been extremely poor" and that some specialists who wish to maintain earlier high estimates of the Stalinist death toll are "finding it difficult to adapt to the new circumstances when the archives are open and when there are plenty of irrefutable data" and instead "hang on to their old Sovietological methods with round-about calculations based on odd statements from emigres and other informants who are supposed to have superior knowledge".[71][3]

| Event | Estimated number of deaths | References |

|---|---|---|

| Dekulakization | 530,000–600,000 | [72] |

| Great Purge | 777,975–1,200,000 | [8][44] |

| Gulag | 1,500,000–1,713,000 | [21][14] |

| Soviet deportations | 450,000–566,000 | [73][74] |

| Katyn massacre | 22,000 | [75] |

| Holodomor | 2,500,000–4,000,000 | [76] |

| TOTAL | ~5,780,000–8,101,000 |

References

- "Soviet Studies". See also: Gellately (2007) p. 584: "Anne Applebaum is right to insist that the statistics 'can never fully describe what happened.' They do suggest, however, the massive scope of the repression and killing."

- Wheatcroft, Stephen (1996). "The Scale and Nature of German and Soviet Repression and Mass Killings, 1930–45" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 48 (8): 1334, 1348. doi:10.1080/09668139608412415. JSTOR 152781.

The Stalinist regime was consequently responsible for about a million purposive killings, and through its criminal neglect and irresponsibility it was probably responsible for the premature deaths of about another two million more victims amongst the repressed population, i.e. in the camps, colonies, prisons, exile, in transit and in the POW camps for Germans. These are clearly much lower figures than those for whom Hitler's regime was responsible.

- Wheatcroft, S. G. (2000). "The Scale and Nature of Stalinist Repression and its Demographic Significance: On Comments by Keep and Conquest" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 52 (6): 1143–1159. doi:10.1080/09668130050143860. PMID 19326595.

- Robert Conquest. The Great Terror. NY Macmillan, 1968 p. 533 (20 million)

- [[Anton Antonov-Ovseyenko],] The Time of Stalin, NY Harper & Row 1981. p.126 (30-40 million)

- Elliot, Gill. Twentieth Century Book of the Dead. Penguin Press 1972. pp. 223-24(20 million)

- Seumas Milne: "The battle for history", The Guardian. (12 September 2002). Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- Haynes, Michael (2003). A Century of State Murder?: Death and Policy in Twentieth Century Russia. Pluto Press. pp. 214–15. ISBN 9780745319308.

- Applebaum, Anne (2003) Gulag: A History. Doubleday. ISBN 0-7679-0056-1 pp 582-83

- Pohl, J. Otto (1997). The Stalinist Penal System. McFarland. p. 58. ISBN 0786403365.

- Pohl, J. Otto (1997). The Stalinist Penal System. McFarland. p. 148. ISBN 0786403365. Pohl cites Russian archival sources for the death toll in the special settlements from 1941-49

- Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (1999). "Victims of Stalinism and the Soviet Secret Police: The Comparability and Reliability of the Archival Data. Not the Last Word" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 51 (2): 315–345. doi:10.1080/09668139999056.

During 1921–53, the number of sentences was (political convictions): sentences, 4,060,306; death penalties, 799,473; camps and prisons, 2,634397; exile, 413,512; other, 215,942. In addition, during 1937–52 there were 14,269,753 non-political sentences, among them 34,228 death penalties, 2,066,637 sentences for 0–1 year, 4,362,973 for 2–5 years, 1,611,293 for 6–10 years, and 286,795 for more than 10 years. Other sentences were non-custodial

- Davies,; Wheatcroft (2009). The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia Volume 5: The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture 1931-1933. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 401. ISBN 9780230238558.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ellman, Michael (2002). "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (7): 1172. doi:10.1080/0966813022000017177.

- Conquest, Robert (1997). "Victims of Stalinism: A Comment" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 49 (7): 1317–1319. doi:10.1080/09668139708412501.

We are all inclined to accept the Zemskov totals (even if not as complete) with their 14 million intake to Gulag 'camps' alone, to which must be added 4–5 million going to Gulag 'colonies', to say nothing of the 3.5 million already in, or sent to, 'labour settlements'. However taken, these are surely 'high' figures.

- Getty, J. Arch; Rittersporn, Gábor; Zemskov, Viktor (1993). "Victims of the Soviet penal system in the pre-war years: a first approach on the basis of archival evidence" (PDF). American Historical Review. 98 (4): 1017–1049. doi:10.2307/2166597. JSTOR 2166597.

- Applebaum, Anne (2003) Gulag: A History. Doubleday. ISBN 0-7679-0056-1 pg 583: "both archives and memoirs indicate that it was common practice in many camps to release prisoners who were on the point of dying, thereby lowering camp death statistics."

- Ellman, Michael (2002). "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (7): 1153. doi:10.1080/0966813022000017177.

- Alexopoulos, Golfo (2017). Illness and Inhumanity in Stalin's Gulag. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17941-5.

- Hardy, J. (2018). "Review": Illness and Inhumanity in Stalin's Gulag. By Golfo Alexopoulos. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007. xi, 308 pp. Notes. Index. Maps. $65.00, hard bound. Slavic Review, 77(1), 269-270. doi:10.1017/slr.2018.57

- Healey, Dan (1 June 2018). "GOLFO ALEXOPOULOS. Illness and Inhumanity in Stalin's Gulag". The American Historical Review. 123 (3): 1049–1051. doi:10.1093/ahr/123.3.1049.

New studies using declassified Gulag archives have provisionally established a consensus on mortality and "inhumanity." The tentative consensus says that once secret records of the Gulag administration in Moscow show a lower death toll than expected from memoir sources, generally between 1.5 and 1.7 million (out of 18 million who passed through) for the years from 1930 to 1953.

- John G, Heidenrich, (2001). How to Prevent Genocide: A Guide for Policymakers, Scholars, and the Concerned Citizen. Hardcover: Praeger. p. 7. ISBN 978-0275969875. Another 12 million Soviet citizens died in a network of forced labor camps collectively known by the Russian acronym Gulag, many of them from the physical toil of satisfying Stalins’s relentless drive to rapidly industrialize the Soviet Union.

- Wheatcroft, Stephen (1996). "The Scale and Nature of German and Soviet Repression and Mass Killings, 1930–45" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 48 (8): 1330. doi:10.1080/09668139608412415. JSTOR 152781.

When Solzhenitsyn wrote and distributed his Gulag Archipelago it had enormous political significance and greatly increased popular understanding of part of the repression system. But this was a literary and political work; it never claimed to place the camps in a historical or social-scientific quantitative perspective, Solzhenitsyn cited a figure of 12-15 million in the camps. But this was a figure that he hurled at the authorities as a challenge for them to show that the scale of the camps was less than this.

- Steven Rosefielde. Red Holocaust. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 0-415-77757-7 pg. 67 "...more complete archival data increases camp deaths by 19.4 percent to 1,258,537"; pg 77: "The best archivally based estimate of Gulag excess deaths at present is 1.6 million from 1929 to 1953."

- Davies,; Wheatcroft (2009). The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia Volume 5: The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture 1931-1933. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 415. ISBN 9780230238558.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)This is the estimate of Wheatcroft and Davies

- Andreev EM; Darsky LE; Kharkova TL, Population dynamics: consequences of regular and irregular changes. in Demographic Trends and Patterns in the Soviet Union Before 1991. Routledge. 1993; ISBN 0415101948 p.431("This indicates general collectivization and repressions connected with it, as well as the 1933 famine, may be responsible for 7 million deaths")

- Conquest, Robert (1886). Harvest of Sorrow. Oxford. p. 304. ISBN 0195051807.

- Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands. Basic Books. pp. 21–58. ISBN 9780465002399.

- Naimark, Norman M. Stalin's Genocides (Human Rights and Crimes against Humanity). Princeton University Press, 2010. pp. 51-79. ISBN 0-691-14784-1

- Ellman, Michael (2005). "The Role of Leadership Perceptions and of Intent in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1934" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. Routledge. 57 (6): 823–41. doi:10.1080/09668130500199392. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- Naimark, Norman M. Stalin's Genocides (Human Rights and Crimes against Humanity). Princeton University Press, 2010. pp. 134–135. ISBN 0-691-14784-1

- Rosefielde, Steven. Red Holocaust. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 0-415-77757-7 pg. 259

- Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books, 2010. ISBN 0-465-00239-0 pp. vii, 413

- Rosefielde, Steven (1983). "Excess Mortality in the Soviet Union: A Reconsideration of the Demographic Consequences of Forced Industrialization, 1929–1949". Soviet Studies. 35 (3): 385–409. doi:10.1080/09668138308411488. JSTOR 151363.

- "The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia" (PDF). 5 – The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931–1933. Palgrave Macmillan. 2004. Retrieved 28 December 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Davies, R. W. and Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (2004) The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931–1933, ISBN 0-333-31107-8

- Davies, R. W.; Wheatcroft, S. G. (2006). "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932-1933: A Reply to Ellman" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 58 (4): 625–633. doi:10.1080/09668130600652217.

- Andreev, EM, et al. (1993) Naselenie Sovetskogo Soiuza, 1922–1991. Moscow, Nauka, ISBN 5-02-013479-1

- Ghodsee, Kristen R. (2014). "A Tale of "Two Totalitarianisms": The Crisis of Capitalism and the Historical Memory of Communism" (PDF). History of the Present. 4 (2): 124. doi:10.5406/historypresent.4.2.0115.

- Ganson, N. (2009). The Soviet Famine of 1946-47 in Global and Historical Perspective. Springer. p. 194. ISBN 9780230620964.

- Raleigh, Donald J. (2001). Provincial Landscapes: Local Dimensions of Soviet Power, 1917-1953. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780822970613.

- Magocsi, Paul R. (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. University of Toronto Press. p. 799. ISBN 978-1-4426-1021-7. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- Tauger, Mark B. (2001). "Natural Disaster and Human Actions in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1933". The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies (1506): 1–65. doi:10.5195/CBP.2001.89. ISSN 2163-839X. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017.

- Ellman, Michael (2002). "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (7): 1151–1172. doi:10.1080/0966813022000017177.

The best estimate that can currently be made of the number of repression deaths in 1937–38 is the range 950,000–1.2 million, i.e . about a million. This is the estimate which should be used by historians, teachers and journalists concerned with twentieth century Russian—and world—history

- Michael Ellman Archived 14 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The 1947 Soviet Famine and the Entitlement Approach to Famines Cambridge Journal of Economics 24 (2000): 603-630.

- Polian, Polian (2004). Against Their Will. Hungary: Central European Press. p. 313. ISBN 9639241687.

- Archived 14 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- Sebag Montefiore, Simon (2014). Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. W&N. p. 84. ISBN 978-1780228358. "By 1937, 18,5 million were collevtivized but there were now only 19.9 million households: 5.7 million households, perhaps 15 million persons, had been deported, many of them dead"

- Pohl, J. Otto (1997). The Stalinist Penal System. McFarland. p. 148. ISBN 0786403365.

- Kużniar-Plota, Małgorzata (30 November 2004). "Decision to commence investigation into Katyn Massacre". Departmental Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. New York. p. 384.

- Snyder, Timothy (27 January 2011). "Hitler vs. Stalin: Who Was Worse?". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

" The total number of noncombatants killed by the Germans—about 11 million—is roughly what we had thought. The total number of civilians killed by the Soviets, however, is considerably less than we had believed. We know now that the Germans killed more people than the Soviets did . . . All in all, the Germans deliberately killed about 11 million noncombatants, a figure that rises to more than 12 million if foreseeable deaths from deportation, hunger, and sentences in concentration camps are included. For the Soviets during the Stalin period, the analogous figures are approximately six million and nine million. These figures are of course subject to revision, but it is very unlikely that the consensus will change again as radically as it has since the opening of Eastern European archives in the 1990s.

- Montefiore 2004, p. 649: "Perhaps 20 million had been killed; 28 million deported, of whom 18 million had slaved in the Gulags".

- Volkogonov, Dmitri (1998). Autopsy for an Empire: The Seven Leaders Who Built the Soviet Regime. p. 139. ISBN 0-684-83420-0.

Between 1929 and 1953 the state created by Lenin and set in motion by Stalin deprived 21.5 million Soviet citizens of their lives.

- Yakovlev, Alexander N.; Austin, Anthony; Hollander, Paul (2004). A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia. Yale University Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-300-10322-9.

My own many years and experience in the rehabilitation of victims of political terror allow me to assert that the number of people in the USSR who were killed for political motives or who died in prisons and camps during the entire period of Soviet power totaled 20 to 25 million. And unquestionably one must add those who died of famine – more than 5.5 million during the civil war and more than 5 million during the 1930s.

- Gellately (2007) p. 584: "More recent estimations of the Soviet-on-Soviet killing have been more 'modest' and range between ten and twenty million." and Stéphane Courtois. The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror Repression. Harvard University Press, 1999. p. 4: "U.S.S.R.: 20 million deaths."

- Brent, Jonathan (2008) Inside the Stalin Archives: Discovering the New Russia. Atlas & Co., 2008, ISBN 0-9777433-3-0"Introduction online" (PDF). Archived from the original on 24 February 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2009.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) (PDF file): Estimations on the number of Stalin's victims over his twenty-five-year reign, from 1928 to 1953, vary widely, but 20 million is now considered the minimum.

- Rosefielde, Steven (2009) Red Holocaust. Routledge, ISBN 0-415-77757-7 p.17: "We now know as well beyond a reasonable doubt that there were more than 13 million Red Holocaust victims 1929–53, and this figure could rise above 20 million."

- Naimark, Norman (2010) Stalin's Genocides (Human Rights and Crimes against Humanity). Princeton University Press, p. 11: "Yet Stalin's own responsibility for the killing of some fifteen to twenty million people carries its own horrific weight ..."

- [53]>[54][55][56][57][58][59]

- Richard Pipes, Communism: A History, USA, 2001. p. 67

- Conquest, Robert (2007) The Great Terror: A Reassessment, 40th Anniversary Edition, Oxford University Press, in Preface, p. xvi: "Exact numbers may never be known with complete certainty, but the total of deaths caused by the whole range of Soviet regime's terrors can hardly be lower than some fifteen million."

- Regimes murdering over 10 million people. hawaii.edu

- Rummel, R.J. (1 May 2006) How Many Did Stalin Really Murder?

- Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (1999). "Victims of Stalinism and the Soviet Secret Police: The Comparability and Reliability of the Archival Data. Not the Last Word" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 51 (2): 340–342. doi:10.1080/09668139999056.

For decades, many historians counted Stalin’ s victims in `tens of millions’, which was a figure supported by Solzhenitsyn. Since the collapse of the USSR, the lower estimates of the scale of the camps have been vindicated. The arguments about excess mortality are far more complex than normally believed. R. Conquest, The Great Terror: A Re-assessment (London, 1992) does not really get to grips with the new data and continues to present an exaggerated picture of the repression. The view of the `revisionists’ has been largely substantiated (J. Arch Getty & R. T. Manning (eds), Stalinist Terror: New Perspectives (Cambridge, 1993)). The popular press, even TLS and The Independent, have contained erroneous journalistic articles that should not be cited in respectable academic articles.

- Getty, J. Arch; Rittersporn, Gábor; Zemskov, Viktor (1993). "Victims of the Soviet penal system in the pre-war years: a first approach on the basis of archival evidence" (PDF). American Historical Review. 98 (4): 1017–1049. doi:10.2307/2166597. JSTOR 2166597.

The long-awaited archival evidence on repression in the period of the Great Purges shows that levels of arrests, political prisoners, executions, and general camp populations tend to confirm the orders of magnitude indicated by those labeled as “revisionists” and mocked by those proposing high estimates.

- Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2003). Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 643. ISBN 9780307427939.

- Conquest, Robert (September–October 1996). "Excess Deaths in the Soviet Union". New Left Review. Vol. I no. 219. Newleftreview.org. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2003). Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-1-842-12726-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gellately 2007, p. 256.

- Wheatcroft, S. G. (1996). "The Scale and Nature of German and Soviet Repression and Mass Killings, 1930–45" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 48 (8): 1330. doi:10.1080/09668139608412415. JSTOR 152781.

- Hildermeier, Manfred (2016). Die Sowjetunion 1917-1991. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 35. ISBN 9783486855548.

- Buckley, Cynthia J.; Ruble, Blair A.; Hofmann, Erin Trouth (2008). Migration, Homeland, and Belonging in Eurasia. Woodrow Wilson Center Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0801890758. LCCN 2008-015571.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rywkin, Michael (1994). Moscow's Lost Empire. Routledge. ISBN 9781315287713. LCCN 93029308.

- "Russian parliament condemns Stalin for Katyn massacre". BBC News. 26 November 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Andriewsky, Olga (2015). "Towards a Decentred History: The Study of the Holodomor and Ukrainian Historiography". Journal of Ukrainian Studies. 2 (1): 28. doi:10.21226/T2301N.