Esther Nisenthal Krinitz

Esther Nisenthal Krinitz (1927 – 30 March 2001) was a Polish artist.

Early Life

Esther Nisenthal (married name Krinitz) was born a Jew in 1927 in a small hamlet, Mniszek in Poland [1] , the second in a family of 5 children and the oldest girl.

Her father was Hersh, her mother was Rachel; her older brother, Ruven; and later her sisters, Mania, Chana and Leah came along, they all lived near their grandparents, aunts, uncles and five cousins.[1]

Esther learned to sew with a local dressmaker when she was nine. Four years later, her quiet rural life was turned upside down by the Nazi invasion, and she eventually sewed her story in a collage.[1]

Nazi invasion and treatment of Jews

In September 1939, as a 12-year-old, Esther watched Nazi German soldiers arrive in her village of Mniszek, strategically located along the east bank of the Vistula River. Her grandfather was pulled from his home, beaten and had his beard publicly shaved off ( a sign of the Jewish faith, removed to demonstrate the racial / religious hatred and power of the Nazi regime).[1] One Passover meal preparation day, when special food is laid out according to the Jewish faith, two soldiers came right into the Krinitz house, pulled the tablecloth away, making all the symbolic items and dishes fall and break, and they also confiscated a goose being kept especially for the Jewish family's feast.[1]

For the next 3 years, German troops used Jewish slave laborers from Mniszek and the nearby city of Rachów to build roads and bridges for their Eastern campaign. Her family had managed to struggle through the German occupation, watching their already-meager livelihood dwindle to nearly nothing. Her father, a horse trader, could no longer travel. Soldiers had taken the last of her mother's geese just as her eggs were about to hatch.

Once the Nazis moved to implement what became known as the "Final Solution", however, the Jews of Rachów and Mniszek—those who had not already been murdered—were instructed to leave their homes and report to the train station in Kraśnik, about 20 miles away. No one knew where they were going. Many thought they were going to be taken to a ghetto somewhere. Others whispered darkly of death camps.

This was in 1942, Esther was by then 15. Raids had already happened when the family had to hide in the woods; Esther had been hit by a soldier's rifle butt for not putting her hands up high enough. And before the Gestapo arrived at dawn on 15 October 1942, to remove Jews in the village,[1] as her family assembled what few belongings remained to them, Esther had already decided she would not go with them. Her parents thought they were being removed to a ghetto for Jews, but she felt they would be sent to a concentration camp, or to be killed.[1]

Her family was taken out in their nightwear, lined up at gunpoint, but neighbours pleaded successfully for their lives.[1]

Despite the risk, Esther persuaded her parents to let herself and thirteen year old sister Mania try to escape the evacuation.[1]

She turned to her mother for help, insisting that one of the Polish farmers among her father's friends would take her in and give her work. Although at first reluctant to let her go, Esther's mother agreed to give her some provisions and destinations.

As the family said their goodbyes to her, Esther realized she could not carry out her plan by herself and insisted that her 13-year-old sister, Mania, go with her. Mania was reluctant, wanting only to stay with the rest of the family, but Esther was emphatic. So on October 15, 1942, her father, Hersh; her mother, Rachel; her older brother, Ruven; and her little sisters, Chana and Leah, and other Jews were set off on the road to Kraśnik.

It was the last time Esther saw her family.[1]

Escape The next three sections need inline citations

Mania was heartbroken and cried to go back to their family. Giving in, Esther turned back with her to the Kraśnik road, filled by now with a stream of refugees. Esther and Mania joined them, walking with their cousin Dina and her baby past fields and through the sandhills of the valley. As they walked on, Esther realized that the next bend in the road would lead to the train station, and she halted in panic, insisting that she could not continue. At this, their cousin turned to Mania and told her she should leave the road and go with her sister.

Esther and Mania went first to the house of Stefan, a good man who embraced them when they arrived. But after sheltering them for a couple of days, Stefan told them that the rest of the village knew where they were and that the Gestapo would soon come looking for them. In tears, he put them out of his house.

Knowing now that it was not safe for them to be seen, Esther and Mania waited in the forest until the rain ended and their clothes dried. While they waited, Esther devised a plan: They would make their way to another village where they were not known. There, they would say that they had come from the northern part of Poland, where their family, like others in the region, had lost its farm to a German family. With their digging tools in sacks across their shoulders, they would ask for work in harvesting potatoes.

Grabówka

They eventually came to the village of Grabówka. Pretending to be a Polish Catholic girl named Josephina, Esther found work with an old farmer whose wife was ill and bedridden. Mania also became a housekeeper, for the village's sheriff and his mother. Until 1944, Esther and Mania cooked, cleaned, cared for animals, helped in the fields, went to church, and lived out the daily lives of two Polish farm girls.

Although the Germans did not have a camp in the village, the Gestapo were stationed nearby and soldiers came and went in the village frequently, commandeering food and other supplies as they needed them. They also took young people for labor camps, now that the Jews had been eliminated. So even though she was assumed to be Polish, Esther was still forced to run up to the attic of the barn to hide when the Germans were seen to be in the village.

In May 1944, after both the farmer and his wife had died and Esther was living on the farm by herself, an old soldier in Grabówka, a veteran of the First World War, told his neighbors that he could hear artillery fire in the distance to the east. The Russians were pushing the Germans back across Poland, and the old soldier predicted that the front would be in their village within a few days. Under his direction, the neighbors dug out a bunker and prepared to go below. The battle front arrived as predicted, and the neighbors spent a night in the bunker as the German and Russian artillery engaged on the ground immediately above them.

Liberation

That day, at sunset, a platoon of Soviet soldiers arrived in Grabówka. Esther and her neighbors ran to greet them. After waiting 2 weeks, Esther left for Mniszek to see who else had returned. When she arrived in Mniszek, her former neighbors were shocked to see her. Only a few other Jews had come back. All the rest were rumored to have been taken to a death camp nearby to Lublin called Majdanek or Maidanek.

Unable to find the rest of her family, Esther decided to join the Polish Army, then continuing on its way west to Warsaw under Marshal Zhukov's command.

Before she left, Esther set out to see Majdanek for herself. The Polish Army had taken over the camp, and soldiers who had been there for a while served as guides, taking new recruits around to point out the horrors inflicted by the Nazis. Esther noticed the enormous cabbages growing in the fields around the crematorium, later learning that it had been the dumping site for ashes. She saw the piles of shoes, and learned about the massacre at nearby Krepicki Forest, where 18.000 Polish Jews were slaughtered in November 1943.[1]

With Marshal Zhukov's army, Esther eventually arrived in Germany.[1]

After the war

After the war ended in 1945, Esther returned to Grabówka to get Mania and in 1946, the two of them returned to Germany, making their way to a Displaced Persons camp in the favored American Zone, in the city of Ziegenheim.

She met Max Krinitz there and, in November 1946, married him in a ceremony conducted in the camp. The following year, pregnant with their first child, Esther joined Max in Belgium, where he had gone to work in the coal mines. While in Belgium, he contacted a cousin who lived in the United States and she agreed to arrange for sponsorship of his immigration.

In June 1949, Esther, Max and their daughter emigrated to the United States of America, she was only 22,[1] when they arrived in New York.

Return to Poland

In June 1999, exactly 50 years after she left Europe, Esther returned to Mniszek to see what remained. The landscape of central Poland had not changed: farmers driving horse-drawn wooden wagons, red and yellow fields of poppy and mustard, women carrying baskets overflowing with ripe strawberries. Both in Mniszek and Grabówka, Esther met again with friends and neighbors from her childhood. "Yes, it was just like that!" they said when she showed them photographs of her sewn art.

Immediately following her return from Poland, Esther became seriously ill; she died 30 March 2001[2] at the age of 74.

Embroidered art

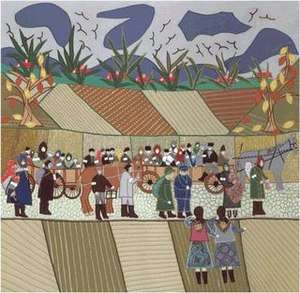

Esther Nisenthal Krinitz began the first of her series of 36 panels [1] of fabric pictures in 1977, with a depiction of her home and family in Mniszek. Although trained as a dressmaker and highly skilled in needlework, Esther had no training in art and no conception of herself as an artist. Yet her first picture was so well received by her family and friends and was so personally satisfying that Esther went on to do another, also of her childhood home.

The next subjects for her art were two dreams she had had while hiding in Grabówka. Each dream—one in which her grandfather had appeared to her and another in which her mother came for her—had left singular vivid images in Esther's memory, and translating them into pictures was an important accomplishment for her. Once the dream sequence was completed, Esther decided to begin a narrative series that grew increasingly complex. With the addition of text, her art became illustrations of Esther's story of survival.

The contrast in her art in cloth and stitching shows between normal life and horror: flowers and prison camp fencing; the pattern of her dress hiding her from soldiers as a child in the fields; her sisters pretty and ribboned, her grandmother's apron and grandfather's abandoned shoe when he is dragged away and his beard cut; floral cloth for hedges and fields, striped cloth for walls and outhouses; to a small family with suitcases at the Statue of Liberty using her sewing as 'an act of restoration'...'reminiscing'.. 'remembering'..'a slow journey of re-creation.'[1]

Art and Remembrance

Art and Remembrance is traveling an exhibit of Esther Nisenthal Krinitz's to museums in the United States of America, and in the future hopes to bring the art to Poland, Israel and other countries that share the legacy of the Holocaust. The entire collection began its public exhibitions at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland and has subsequently been exhibited at more than a dozen museums in the US .

In 2012, it returned to the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, where it will stay until September 1, 2013.

Future exhibits include the Florida Holocaust Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida and the Evansville Museum of Art and Science in Evansville, Indiana.

In 2011, Art and Remembrance completed the 30-minute documentary film, "Through the Eye of the Needle: The Art of Esther Nisenthal Krinitz." The film tells the story of her harrowing experiences surviving the Holocaust in Poland and how she came to create an amazing and beautiful narrative in embroidery and fabric collage through images of Esther’s artwork, and the story in her own voice, as well as interviews with family members and others.

"Trained as a dressmaker but with no training in art, Esther picked up a needle and thread, intending simply to show her children all that she had gone through. Yet the art she created -- both beautiful and shocking -- is universal in its appeal, expressing deep love of family and personal courage in the face of terror and loss," says the Smithsonian.[3]

References

- Hunter, Clare (2019). Threads of life : a history of the world through the eye of a needle. London: Sceptre (Hodder & Stoughton). pp. 159–162. ISBN 9781473687912. OCLC 1079199690.

- Rosenfeld, Megan (10 May 2001). "A Survivor's Poignant Patchwork of Memories; Esther Krinitz Told Her Story in Needlework, Washington Post". Art & Remembrance. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- https://www.si.edu/Exhibitions/Fabric-of-Survival-The-Art-of-Esther-Nisenthal-Krinitz-4765