Environmental issues in Appalachia

Environmental issues in Appalachia, a cultural region in the Eastern United States, include long term and ongoing environmental impact from human activity, and specific incidents of environmental harm such as environmental disasters. A mountainous area with significant coal deposits, many environmental issues in the region are related to coal and gas extraction.

Coal mining

Rural communities in Appalachia suffer from environmental, economic and health disparities related to coal mining. Environmental activism has tended to be a divisive issue because of the dependence of the regional economy on extractive industries, including coal mining.[1] Environmental disasters related to coal mining include coal seam fires (Carbondale mine fire, Centralia mine fire, and Laurel Run mine fire) and coal slurry spills.

History

Coal was found in the 1740s in Virginia, but use remained small scale until the 1800s.[2] Mountaintop removal mining has been practiced since the 1960s.[3]

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 (SMCRA) was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter, after being vetoed twice by Gerald Ford. Before SMCRA most coal states had passed their own mining laws. SMCRA states that "reclaimed land must be as useful as the land was before mining".[4]

SMCRA also created the Office of Surface Mining, an agency within the Department of the Interior, to promulgate regulations, to fund state regulatory and reclamation efforts, and to ensure consistency among state regulatory programs.[5]

Early attempts to regulate strip-mining on the state level were largely unsuccessful due to lax enforcement. The Appalachian Group to Save the Land and the People was founded in 1965 to stop surface mining. In 1968, Congress held the first hearings on strip mining. Ken Hechler introduced the first strip-mining abolition bill in Congress in 1971. Though this bill was not passed, provisions establishing a process to reclaim abandoned strip mines and allowing citizens to sue regulatory agencies became parts of SMCRA.[6]

After SMCRA was passed, the coal industry immediately challenged it as exceeding the limits of Congressional leglative power under the Commerce Clause.[7] In Hodel v. Virginia Surface Mining and Reclamation Association (1981) the Supreme Court held that Congress does have the authority to regulate coal mining, generally.[8]

The War on Coal

Some organizations have said that the Obama Administration's EPA and other federal agencies were engaged in a "war on coal". Organizations such as The American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity (ACCCE), member companies of the National Mining Association, the United States Chamber of Commerce, as well as anonymous donor political action committees (PACs) spent millions of dollars to promote this message through print, radio and television advertisements. They argued that the proposed regulatory actions would increase the costs of mining and burning coal. They further argued that the regulations would increase the costs of disposing of mining wastes, destroy tens of thousands of jobs, and threaten the "way of life" of coalfield families.

Several categories of federal regulations are at issue:[9]

- The Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), including lowering levels of black-lung causing coal dust and enforceable standards to identify "patterns of violations" by mining companies

- EPA Clean Water Act Regulatory Proposals including efforts to identify buffer zones near streams where mountaintop removal strip-mining and disposal of coal mining wastes would be prohibited

- EPA Clean Air Act proposals

A study conducted by the Great Lakes Energy Institute has found that fracking has driven the decline in coal production in the United States. Professor Mingguo Hong has said that while the EPA rules may have an impact, the data shows that the regulations have not been the driving force behind the decline of coal production.[10]

Mountaintop mining

Mountaintop mining, also called mountaintop removal (MTR), is a form of strip mining and surface mining. This mining process uses explosives to blast the tops of mountains and access underlying coal deposits.[11] It has resulted in mountains being flattened into "synthetic prairies."[12] Researchers have found that mountaintop mining (MTM) is more damaging to rivers, biodiversity and human health then underground mining.[13]

After the 1990 Amendments to the Clean Air Act established a trading and quota system for sulfur dioxide emissions, coal-burning plants began to demand more low-sulfur coal. In response to this increase in demand, mining companies expanded extraction in areas with significant low sulfur coal deposits—in particular, the Appalachian Mountains of West Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, southern Virginia, and eastern Tennessee.[11]

After the mountaintops are blasted to reveal low-sulfur coal deposits, the excess rock and earth created by mountaintop removal is dumped into the valleys. This has buried hundreds of miles of streams under dumped earth.[12] The Charleston Daily Mail reported that MTR has buried 2,000 miles of streams in Appalachia and has contaminated water supplies an endangered the health of Appalachian communities.[14]

Under federal law, mountaintop removal is only allowed if mine operators planned to build schools, shopping centers, factories or public parks on the flattened land. A spokeswoman for the National Mining Association has said "these reclamation activities have provided much needed level land above the flood plain for construction of schools, government offices, medical facilities, airports, shopping centers and housing developments."[15] However, a 2010 survey of 410 mountaintop removal sites found that only 26 of the sites (6.3 percent of total) "yield some form of verifiable post-mining economic development."[16] Joe Lovett is the founder of the Appalachia Center for the Economy and Environment[11] and an attorney who has filed a federal lawsuit against the West Virginia Division of Environmental Protection for issuing mountaintop removal permits without the required post-mining land use plans. Lovett has said the "coal companies are simply taking off mountaintops and dumping them into West Virginia's streams, harming the communities and the environment in the process."[17]

Health effects

Cancer rates in Central Appalachia are higher than elsewhere in the United States.[18] Researchers who have studied the disproportionate rates of cancer in this region have found that there are many contributing factors including poverty and poor health habits.[19] The link between mining and health is controversial. Studies that controlled factors like smoking and obesity have found that cancer, heart disease and birth defects are "associated" with MTM.[19] Cancers are more common in MTM areas. A U.S. Geological Survey found high levels of the carcinogens aluminum and silica in air samples from MTM regions in Appalachia. The researchers also found traces of chromium, sulfate, selenium and magnesium in the air.These components of granite rock may elevate the risk of cancer through respiratory damage.[18] Another study found elevated levels of another carcinogen, arsenic, in toenail samples collected from residents of Appalachian Kentucky.[18]

Fracking

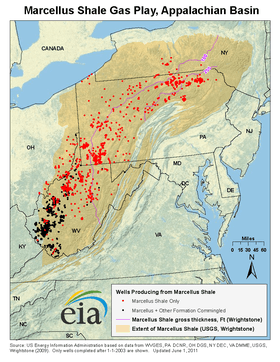

Fracking is a colloquial term for "horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing." [20] During the 19th century natural gas was easy to extract from moderate depths using vertical wells. Sometimes wells were not needed at all because the gas was so plentiful it would bubble up from the ground.[1] As non-renewable energy resources become more scarce, advances in fracking technology have allowed access to natural gas reserves accumulated in shale formations. Reserves of natural gas in the Marcellus Shale rock formation are valued at around $500 billion in Pennsylvania alone.[20]

While coal production in Appalachia has been in decline, advances in fracking technology have contributed to the regional "natural gas boom." The coal deposit of eastern Kentucky and southern West Virginia's coal fields have been mined longer than other reserves in the United States. The remaining deposits in these areas are deeper and the costs of extraction has increased.[21]

Adverse environmental and health impacts have been reported by communities who live near areas with significant fracking activity.[22] Studies have shown that fracking may be a cause of groundwater contamination.[1]

One issue that has been raised is the disposal of wastewater created by the fracking process. The salty wastewater contains dissolved solids like sulfates and chlorides, which sewage and drinking water plants are unable to remove. West Virginia has asked sewage treatment plants to not accept frack water after regulators determined that the levels of dissolved solids in drinking water exceeded government standards.[23]

There are concerns about the environmental and health impacts of the entire process - from site preparation to waste management.[1] Environmental activists have called for a ban on fracking.[22]

Atgas 2H well blowout and spill

In 2011 a study funded by Chesapeake Energy found that the release of fracking fluids from Chesapeake's Atgas 2H well site had not had any long-term negative impact on Pennsylvania groundwater or watersheds.[24] Thousands of gallons of waste fluids spilled onto a farm and streams after the Atgas 2H well in LeRoy Township blew out.[25]

Clearfield County well blowout

During exploration of the Marcellus Shale in 2010, a blowout at the Clearfield County well started a 16-hour natural gas leak. Natural gas and wastewaster "shot 75 feet into the air," releasing 1 million gallons of brine and gas into the forest according to Bud George.[26]

Events

Buffalo Creek Disaster

In 1972, a slurry pond built by Pittson Coal Company collapsed. In what is known as the Buffalo Creek disaster 130 million gallons of sludge flooded Buffalo Creek. More recently, a waste impoundment owned by Massey burst in Kentucky, flooding nearby streams with 250 tons of coal slurry.[27]

When lawyers attempted to sue Pittson Company, the sole shareholder of the Buffalo mining company, they first had to pierce the corporate veil. Pittson's lawyers filed certain documents with the court to show that, as a shareholder, Pittson was not liable for the disaster because the Buffalo Mining Company was run independently. These documents were minutes of shareholders' and directors' meetings that Pittson's attorneys relied on in their argument that Pittson was a protected shareholder behind the corporate veil. The lawyers for the victims of Buffalo creek were able to pierce the corporate veil when they proved that none of these meetings "had actually taken place."[28]

2000 Kentucky coal slurry spill

The Martin County coal slurry spill occurred on October 11, 2000 when the bottom of a coal slurry impoundment owned by Massey Energy in Martin County, Kentucky broke into an abandoned underground mine below. The slurry came out of the mine openings, sending an estimated 306,000,000 US gallons (1.16×109 l; 255,000,000 imp gal) of slurry down two tributaries of the Tug Fork River.[29]

2008 Tennessee fly ash slurry spill

The TVA Kingston Fossil Plant coal fly ash slurry spill occurred on December 22, 2008, when an ash dike ruptured at an 84-acre (0.34 km2) solid waste containment area at the Tennessee Valley Authority's Kingston Fossil Plant in Roane County, Tennessee. 1.1 billion US gallons (4,200,000 m3) of coal fly ash slurry was released.[30]

2014 Elk River chemical spill

The 2014 Elk River chemical spill occurred on January 9, 2014 when 7,500 gallons of chemicals leaked from a Freedom Industries facility into the Elk River, a tributary of the Kanawha River in West Virginia. The primary chemical, crude MCHM, is a chemical foam used to wash coal and remove impurities. The spill resulted in a temporary “do-not-use" advisory for drinking water affecting up to 300,000 people in the area.[31]

Environmental Justice Movement

Environmental justice has been identified by scholars as a movement that acknowledged the disproportionate effects of environmental damage and toxic contamination on the poor and people of color. It has also been noted that the race and class of the parties effects the community's chances of success in enacting reforms. Environmental justice groups were community grassroots organizations that combined environmentalism with issues of race a class equality.[32] These groups organized in opposition to the disproportionate threat mountain communities faced from health hazards like acid mine drainage.[33]

See also

References

- Morrone, Michele (2015). "A Community Divided: Hydraulic Fracturing in Rural Appalachia". Journal of Appalachian Studies. 21 (2): 207–228. doi:10.5406/jappastud.21.2.0207.

- A brief history of coal mining, US Department of Energy, accessed 7 Oct. 2015.

- Copeland, C. (2004). "Mountaintop removal mining". In Humphries, M. U.S. Coal: A Primer on the Major Issues. Nova Publishers. ISBN 1-59454-047-0.

- Howard, Jason (2009). "Hope for Appalachia". Appalachian Heritage. The University of North Carolina Press. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "About OSMRE - Who We Are". www.osmre.gov. December 15, 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Loeb, Penny (2015). Moving Mountains. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 54–55. ISBN 9780813156569.

- Rivkin, Dean Hill; Irwin, Chris (2009). "Strip-Mining and Grassroots Resistance in Appalachia: Community Lawyering for Environmental Justice". Los Angeles Public Interest Law Journal. 2 (1): 168. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- Pendergrass, John A. (1986). "Coal Mining of Federal Lands". Natural Resources & Environment. 2 (1): 19. JSTOR 40912325.

- McGinley, Patrick (Spring 2013). "Collateral Damage: Turning a Blind Eye to Environmental and Social Injustice in the Coalfields". Journal of Environmental and Sustainability Law. 19 (2): 304–425.

- "Shale gas, not EPA rules, has pushed decline in coal-generated". Science Daily. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- Baller, Mark; Pantilat, Leor Joseph (2007). "Defenders of Appalachia: the campaign to eliminate mountaintop removal coal mining and the role of Public Justice". Environmental Law. 37 (3). pp. 629–. ISSN 0046-2276. – via General Onefile (subscription required)

- Vollers, Maryanne (1999). "Razing Appalachia:: first they dug out the land. Then they strip mined it. Now Big Coal is leveling the mountains themselves--and tearing communities apart". Mother Jones. 24 (4). pp. 36–. ISSN 0362-8841. – via General Onefile (subscription required)

- Fabricant, Nicole (2015). "Resource Wars: An On the Ground Understanding of Mountaintop Removal Coal Mining in Appalachia, West Virginia". Radical Teacher. 102: 8–16. doi:10.5195/rt.2015.185. ISSN 0191-4847.

- Noppen, Trip Van (2010-08-11). "W.Va. can't afford mountaintop mining: ; For communities, economies to live, it must be stopped". Charleston Daily Mail. Archived from the original on 2018-11-19. Retrieved 2017-05-23. – via HighBeam (subscription required)

- Jafari, Samira (19 November 2006). "Mountaintop Mining, As Seen From Above; Photos Show Damage to Appalachians". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 2017-05-23. – via HighBeam (subscription required)

- May 17; 2010. "The Myth of Mountaintop Removal Reclamation". NRDC. Retrieved 2019-12-13.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Ward Jr., Ken (1998-08-09). "MINING THE MOUNTAINS: FLATTENED; Most mountaintop mines left as pasture land in state". Sunday Gazette-Mail. Archived from the original on 2018-11-20. Retrieved 2017-05-23. – via HighBeam (subscription required)

- Wapner, Jessica (19 July 2015). "The Cancer Epidemic in Central Appalachia". Newsweek. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- Estep, Bill (6 June 2017). "Where you live in Kentucky might cut eight years off your life". Lexington Herald Leader. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- "The Shale Rebellion: How Appalachia Became a Battleground in the Fight Over Fracking". Public Square Media. Moyers & Company. 12 December 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- Sheldon, Elaine McMillion. "Can President Trump Keep His Promises to Coal Country?". PBS. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- Carpenter, Zoë (20 July 2016). "A New Study Adds Fuel to Calls for a Fracking Ban". The Nation. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- Levy, Marc (3 February 2010). "NATURAL GAS DRILLING: ; Byproduct poses threat to Appalachia 'Fracking' brine can foul groundwater". The Charleston Gazette. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2017 – via HighBeam Research.

- "Marcellus fracking: Facts & Fictions". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. 31 October 2011. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2017 – via HighBeam Research.

- Legere, Laura (20 April 2011). "Natural Gas Well Blows Out, Releasing Fluids In Bradford County". Republican & Herald. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2017 – via HighBeam Research.

- Puko, Tim (5 June 2010). "arcellus Blowout Sprays Gas in Clearfield County". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Retrieved 20 May 2017 – via HighBeam Research.

- Thomas, Erin Ann (2012). Coal in our Veins: A Personal Journey. University Press of Colorado. p. 168. JSTOR j.ctt4cgrkb.20.

- Stern, Gerald M. (2008). The Buffalo Creek disaster: How the Survivors of one of the Worst Disasters in Coal-Mining History Brought Suit Against the Coal Company and Won. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 9780307388490.

- Sealey, Geraldine (October 23, 2000). "Sludge Spill Pollutes Ky., W. Va. Waters". ABC News. Retrieved 2017-05-05.

- DEWAN, SHAILA (8 December 2008). "Tennessee Ash Flood Larger Than Initial Estimate". New York Times. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- Botelho, Greg; Watkins, Tom (January 11, 2014). "Bottled water for West Virginia residents plagued by chemical in water supply". CNN.com. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- Ferguson, Cody (2015). This is Our Land. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780813565644.

- Eller, Ronald D. (2008). Uneven Ground: Appalachia since 1945. University Press of Kentucky. p. 255. JSTOR j.ctt2jctgr.12.