Ennigaldi-Nanna's museum

Ennigaldi-Nanna's museum is thought by some historians to be the first museum, although this is speculative. It dates to circa 530 BCE.[1][2][3][4] The curator was Princess Ennigaldi, the daughter of Nabonidus, the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire.[5] It was located in the state of Ur, located in the modern-day Dhi Qar Governorate of Iraq, roughly 150 metres (490 ft) southeast of the famous Ziggurat of Ur.[6]

Archeological excavations at the palace grounds | |

Location within Iraq | |

| Established | Circa 530 BCE |

|---|---|

| Dissolved | 5th century-BCE |

| Location | Ancient Ur |

| Coordinates | 30.961667°N 46.105278°E |

| Type | Mesopotamian artifacts |

| Curator | Princess Ennigaldi |

History

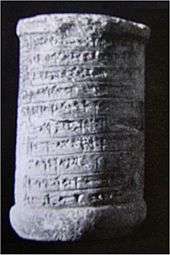

When archaeologists excavated certain parts of the palace and temple complex at Ur they determined that the dozens of artifacts, neatly arranged side by side, whose ages varied by centuries, were actually museum pieces - since they came with what was finally determined to be "museum labels". These consisted of clay cylinder drums with labels in three different languages.[4] Ennigalbi's father Nabonidus, an antiquarian and antique restorer, taught her to appreciate ancient artifacts.[3] Her father is known as the first serious archeologist and influenced Ennigaldi to create her educational antiquity museum.[1]

The palace grounds that included the museum were at the ancient building referred to as E-Gig-Par, which also had her living quarters.[7] The palace grounds also included the palace subsidiary buildings.[4][8][9]

Contents

When archaeologist Leonard Woolley excavated the ruins of the museum, its contents were discovered to be labeled, using tablets and clay drums.[10] Many of the artifacts had been originally excavated by Nabonidus, Ennigald's father, and were from the 20th century BCE. Some artifacts had been collected previously by Nebuchadnezzar.[9] Some are thought to have been excavated by Ennigald herself. The items were many centuries old already in Ennigald's time and came from the southern regions of Mesopotamia.[3]

Ennigald stored the artifacts in a temple next to the palace where she lived.[3] She used the museum pieces to explain the history of the area and to interpret material aspects of her dynasty's heritage.[10]

The "museum labels" (the oldest such known to historians) for the items found in the museum were clay cylinders with descriptive text in three different languages.[6][11]

Some of these artifacts were:

References

- Anzovin & Podell 2000, p. 69, Item # 1824: "The first museum known to historians (circa 530 BCE) was that of Ennigaldi-Nanna, the daughter of Nabu-na'id (Nabonidus), the last king to Babylonia."

- Casey 2009, "Public Museum": "Around 530 B.C.E. in Ur, an educational museum containing a collection of labeled antiquities was founded by Ennigaldi-Nanna the, daughter of Nabonidus, the last king of Babylonia."

- Dolezal 1987, p. 20: "Princess Ennigaldi-Nanna, collected antiques from the southern regions of Mesopotamia, which she stored in a temple at Ur – the first known museum in the world.

- León 1995, pp. 36–37: "...the first known museum..."

- McIntosh 1999, p. 4

- Woolley & Moorey 1982, pp. 252–259

- Woolley 1954, p. 235

- HarperCollins 1997, p. 23

- Nash 2003, p. 12

- Encyclopaedia Britannica 1997, p. 481

- Budge, E. A. (1926). "The Excavations at Ur of the Chaldees". The Book of the Cave of Treasures. p. 275.

Sources

- Anzovin, Steven; Podell, Janet (2000). Famous First Facts, International Edition: A Record of First Happenings, Discoveries, and Inventions in World History. H.W. Wilson. ISBN 978-0-8242-0958-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Encyclopaedia Britannica (1997). The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Vol. 2 (15 ed.). ISBN 978-0-85229-633-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Casey, Wilson (6 October 2009). Firsts: Origins of Everyday Things That Changed the World. DK Publishing. ISBN 978-1-101-15946-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- HarperCollins (1997). HarperCollins atlas of archaeology. Borders Press in association with HarperCollinsPublishers. ISBN 978-0-7230-1005-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dolezal, Robert J. (1987). Reader's Digest Book of Facts. Reader's Digest Association. ISBN 978-0-89577-256-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- León, Vicki (1 January 1995). Uppity Women of Ancient Times. Conari Press. ISBN 978-1-57324-010-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McIntosh, Jane (1999). The Practical Archaeologist: How We Know what We Know about the Past. Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-3950-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nash, Stephen Edward, ed. (September 30, 2003). "Curators, collections, and contexts: anthropology at the Field Museum, 1893-2002". Fieldiana: Anthropology. Field Museum of Natural History. 1525 (36). JSTOR i29782661.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woolley, Leonard; Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart (1982). Ur 'of the Chaldees'. Herbert Press. ISBN 978-0-906969-21-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Woolley, Leonard (1954). Excavations at Ur: A Record of Twelve Years' Work. Great Britain: Ernest Benn Limited. ISBN 978-0-8152-0110-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)