Emil Weiss

Emil Weiss (August 14 1896 – January 6 1965) Illustrator, one of the last “press artists” (that old journalistic specialty superseded by photography, which is undoubtedly faster and perhaps more literally accurate, but seldom as penetrating.)

Emil Weiss | |

|---|---|

| Born | August 14, 1896 Moravia, Czech Republic |

| Died | January 6, 1965 (aged 68) |

| Occupation | Illustrator |

Biography

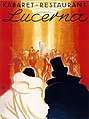

He was born in Moravia, then part of Austria-Hungary, now in the Czech Republic and trained as an architect in Vienna. In Prague of the 1920s, he ran a triple studio: 1. As cartoonist having fun in the newspapers. 2. As commercial artist doing advertising. His very Art-déco posters[1] are on display at the Prague Museum of Applied Arts, where reproductions are on sale as posters and even as miniatures on matchbox covers. 3. As architect. His style was very Art-déco, severely geometrical, with rounded corners, un-decorated, handcrafted of finest materials. All went fine until the Depression and then Hitler destroyed that whole world.

In 1938 he sought refuge in Britain, but was denied a working permit until the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, whereupon his status changed from visitor to refugee. His personal version of English and his European drawing style made it difficult to find work so at 43 he started from zero. He did whatever he could during those difficult years: wartime propaganda posters… illustrations for Czech publications… portrait sketches for the Daily Telegraph… then he met Rose Fyleman, author of children's books and poetry,[2] who was doing a serial for the children's page of the Christian Science Monitor in Boston. He illustrated the weekly segments for her and that led him to Saville Davis, then the Monitor’s London correspondent, who appointed him their London visual reporter. There he covered international events such as the 1946 conference in Lancaster House where the United Nations was born. In 1948 he emigrated to the US and became the Monitor’s artist-reporter covering national events and politicians both on assignment as well as freelance until his death in 1965.

One of his favorite haunts was the UN in New York, where he was often mistaken for a delegate, with his gracious old-world manner, bow tie, and homburg hat. Thus diplomatically camouflaged, he blended into the background, where he would scribble surreptitious notes on any scrap of paper he found in his pocket. Incredibly quickly he caught and pinned down the personal characteristics of his distinguished subjects by their stance and body language. He then scooted back to his studio where he deftly traced the scribbles using his unique dry-brush technique of ink on vellum paper… identified the scene in his somewhat inventive spelling… tossed it in an envelope and rushed to catch the Monitor’s Boston pouch. The drawings bear the working notes of an artist-reporter under deadline. It was not a highly lucrative profession, but he loved its immediacy, its glamor, and the fun of revealing people.

His portrait gallery of some thousand drawings of international personalities is a historic microcosm of the mid-20th Century. Some drawings are straight reportage, some slyly satirical, all expose his victims’ singularity.[3] Aside from his portraits, the Monitor published pages’-worth of his article-illustrations as well as sketches from his travels—many from Austria—for which The President of Austria awarded him their Golden Badge of Honor in 1964.

Illustrator of some 40 children's books[4] (originals now in the Kerlan Collection of the University of Minnesota Library) he illustrated Harper & Row’s young readers’ edition of JFK’s Profiles in Courage; Emily Neville’s 1964 Newbery medal winner It’s like this, cat, Harper & Row, 1963. He was author of My Studio Sketchboook, Marsland, London 1948; with Karla Weiss the children's cookbook Let's have a party, Bruce, London, 1946; as well as Slavische Märchen, Schweizer Druck und Verlagshaus, Zürich, 1952.

A gentle, funny, trusting, hopelessly impractical humanist, he was also childishly superstitious: believed that if you pronounced the name of a medicine with a Latin accent, its effective strength increased. For lower back pain he advised a sheet of red flannel folded in half and draped over a string that wrapped around the waist. Any other color than red was useless. Tucking it inside the pants would shield the wearer from “looking like a truck with a red flag waving behind.” Fortunately his wife, Karla, graduate of the Prague Music Academy, was more practical. She enabled him to do what he simply had to do: to draw. He was never without a pencil in his hand unless he was holding his brush, in which case the pencil was held in his mouth.

He is buried in Mt.Pleasant Cemetery, Hawthorne, New York.

Illustrations

Lucerna cabaret and restaurant, Poster, 1925

Lucerna cabaret and restaurant, Poster, 1925 Sir Winston Churchill, Prime Minister, Great Britain, 06 26 1954

Sir Winston Churchill, Prime Minister, Great Britain, 06 26 1954 Charles de Gaulle, President, France, 08 08 1958

Charles de Gaulle, President, France, 08 08 1958 President Harry S Truman, 08 14 1956

President Harry S Truman, 08 14 1956 President Dwight D. Eisenhower, 01 30 1956

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, 01 30 1956 President John F. Kennedy, 06 11 1963

President John F. Kennedy, 06 11 1963 President Lyndon B. Johnson, 08 24 1964

President Lyndon B. Johnson, 08 24 1964 President Richard M. Nixon, 02 11 1960

President Richard M. Nixon, 02 11 1960 “The New Look, Geneva”: Vyacheslav Molotov, Marshal Zhukov, Nikita S. Khrushchev, Nikolai Bulganin, Andrei Gromyko, Georgi Zarubin, USSR. 07 19 1955

“The New Look, Geneva”: Vyacheslav Molotov, Marshal Zhukov, Nikita S. Khrushchev, Nikolai Bulganin, Andrei Gromyko, Georgi Zarubin, USSR. 07 19 1955 Omar Loutfi, Foreign Minister, Egypt; Adlai Stevenson, USA; Dag Hammarskjold, Secretary General UN. 01 27 1961

Omar Loutfi, Foreign Minister, Egypt; Adlai Stevenson, USA; Dag Hammarskjold, Secretary General UN. 01 27 1961 Emil Weiss Gallery of International Personalities

Emil Weiss Gallery of International Personalities Typical news-drawing and how it was used in the Christian Science Monitor, February 10, 1954.The caption reads: “As the Austrian question reaches Berlin. Left to right, US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav M. Molotov, Austrian Foreign Minister Leopold Figl, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, and French Foreign Minister Georges Bidault. The Austrian discussion is looked for at the end of the week.”

Typical news-drawing and how it was used in the Christian Science Monitor, February 10, 1954.The caption reads: “As the Austrian question reaches Berlin. Left to right, US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav M. Molotov, Austrian Foreign Minister Leopold Figl, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, and French Foreign Minister Georges Bidault. The Austrian discussion is looked for at the end of the week.” Typical news-drawing and how it was used in the Christian Science Monitor, February 10, 1954.The caption reads: “As the Austrian question reaches Berlin. Left to right, US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav M. Molotov, Austrian Foreign Minister Leopold Figl, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, and French Foreign Minister Georges Bidault. The Austrian discussion is looked for at the end of the week.”

Typical news-drawing and how it was used in the Christian Science Monitor, February 10, 1954.The caption reads: “As the Austrian question reaches Berlin. Left to right, US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav M. Molotov, Austrian Foreign Minister Leopold Figl, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, and French Foreign Minister Georges Bidault. The Austrian discussion is looked for at the end of the week.”

References

- Czech Art Deco 1918–1938, The Municipal House, Prague, 1998 pp. 203, 208, 212 Ceska Moda (Czech Fashion) 1918–1939, Uchalova, Olympia and Museum of Applied Arts, Prague, 1996, pp. 9, 38

- Her immortal line “There are fairies at the bottom of our garden” is in Bartlett's Quotations

- The first 80 Years, The Christian Science Monitor 1908–1988 pp. 103, 106, 113, 115, 121, 137

- Illustrators of Children's Books, 1957–1966. Kingman, Horn Book, Boston, 1968 p. 246, lists ten books