Emakimono

Emakimono (絵巻物, emaki-mono, literally 'picture scroll') or emaki (絵巻) are Japanese illustrated handscrolls that have been produced since the 10th century. Emakimono combine both text and image in telling a narrative. They can be "an almost cinematic experience as the viewer scrolls through a narrative from right to left, rolling out one segment with his left land as he re-rolls the right hand portion."[1] They depict a variety of stories including battles, romance, religion, folk tales, and stories of the supernatural world. They are intended to provide cultural information and teach moral values.

History

Handscrolls were first developed in India before the fourth century BCE. They were used for religious texts and entered China by the first century CE. Handscrolls came to Japan centuries later through the spread of Buddhism. The earliest Japanese handscroll was created in the eighth century and focuses on the life of the Buddha.

The Shinto religion also played a significant role in the development of Japanese handscrolls. Handscrolls were often commissioned for Shinto temples and shrines depicting the legends of their founding. Emaki aided in solidifying a distinctly Japanese culture through its use in the arts and literature.

Physical characteristics

Japanese emaki can vary in size. Some "can reach up to forty feet in length."[1] They are painted on paper or silk, backed with paper. The farthest (left) end is fitted with a roller around which the scroll is bound. When rolled up, the scrolls are secured with a braided silk cord and can be safely carried, placed on shelves, or stored in a lacquerware box.

Emakimono are read in incremental sections. One does not unroll the entire scroll and read it in its entirety. Small sections are rolled out by one's right hand while the left hand simultaneously re-rolls the section previously read. It is common for there to be a written account of the story being illustrated either at the start of the scroll, or interspersed between the pictures.

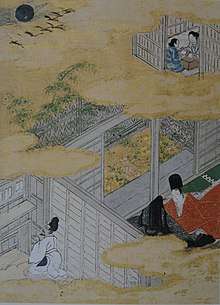

When crafting emaki, artists use a variety of techniques to engage the viewer with the story. The yamato-e genre of painting flourished during the Heian period.[1] It helped to distinguish Japanese subject matter from that of China. Its formal conventions include highly stylized figures, bright, thick pigments, large clouds that divide space, and the use of fukinuki yatai technique. The fukinuki yatai technique, meaning "blown off roof," allows the viewer to onlook the scene from a bird's-eye-perspective. Another stylistic technique used in emaki is hikime kagibana. This refers to the use of profile or back views of figures. No frontal facial views are shown.

Specific details within the illustrations are important in learning the meaning of the story. The clothes, postures, actions, and facial expressions of the figures aide in further explanation of the text.

Well-known examples

There are many well-known examples of emaki. One of the most studied is the Genji Monogatari emaki. The Genji Monogatari emaki is the first handscroll of the Tale of Genji, a story often considered to be the world's first novel. The story follows Genji, the son of a Japanese Emperor and all of his descendants. It reflects the life of the Japanese nobility during the Heian period (794-1195) and features themes including ethics, aesthetics, and politics. Two specific scenes that cover these themes are Bamboo River and Maiden of the Bridge.

Bamboo River tells the story of the competition between suitors for the marriage of Lady Tamakazura's two daughters. Lady Tamakazura is the adopted daughter of Genji and is a member of the court. In the Genji Monogatari emaki rendition, the fukinuki yatai and the hikime kagibana techniques are both used.

Maiden of the Bridge focuses on the character Kaoru, the son of Genji, as he moves to Uji to get away from courtly life. Once in Uji, Kaoru comes upon a bridge where he finds women playing instruments. One woman in particular, Oigimi, he finds to be very beautiful and is overwhelmed by her playing. One section of this scene in the Genji Monogatari emaki displays the women playing music through the use of fukinuki yatai and hikime kagibana. Vibrant colors are also seen throughout this specific emaki. Currently, only 15% of the original scrolls remain, but the fragments are protected as national treasures.

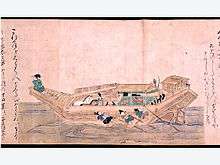

Another specific example of emaki is the Taiheiki emaki. It is considered to be "a record of power struggles which took place between the Kyõto court and the warriors who had established military rule over Japan in the late twelfth century."[2] It tells stories from a half-century of constant warfare. It starts with the enthronement of Emperor Godaigo in 1318 and ends with the death of Yoshiakira, the second Ashikaga shogun in 1367. Similar to the Genji Monogatari emaki, the Taiheiki emaki utilizes fukinuki yatai in its illustrations.

One final example of emaki is the Kitano Tenjin Engi. This emaki memorializes the Legend of the Kitano Shrine. It tells the story of a boy named Michizane who was successful in all aspects of life and was favored by the emperor. This success resulted in jealousy and the spreading of lies. Michizane was eventually exiled to an island where he died of a broken heart. Following his burial on the island, his angry spirit sought revenge through casting violent storms and other natural disasters. A girl named Ayako received a message instructing her and her people to construct a shrine in Michizane's honor, so that the disasters would end. The Kitano Tenmangu shrine built and Michizane's spirit was elevated and named the god of fire, thunder, learning, and scholarship.

Notes

- Willmann, Anna (November 2012). "Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History – Japanese Illustrated Handscrolls". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Murase, Miyeko (1993). "The Taiheiki Emaki: The Use of the Past". Artibus Asiae. 53 (1/2): 262–289. doi:10.2307/3250519. JSTOR 3250519.

References

- "Emakimono: Japanese Picture Scrolls" by contributors to askasia.org, retrieved May 23, 2006

- "Emakimono" by Catherine Pagani, BookRags, retrieved May 23, 2006

- Armbruster, Gisela. Cassoni-Emaki: A Comparative Study. Artibus Asiae, 1972. Murase, Miyeko. The “Taiheiki Emaki”: The Use of the Past. Artibus Asiae, 1993.

- Sayre, Charles Sayre. Japanese Court-Style Narrative Painting of the Late Middle Ages. Duke University Press, 1982.

- Strauch-Nelson, Wendy. Emaki: Japanese Picture Scrolls. National Art Education Association, 2008.

- Watanabe, Masako. Narrative Framing in the "Tale of Genji Scroll": Interior Space in the Compartmentalized Emaki. Artibus Asiae, 1998.

- Waters, Virginia Skord. Sex, Lies, and the Illustrated Scroll: The Dojoji Engi Emaki. Sophia University, 1997.

- Willmann, Anne. Heian Period. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002.

- Willmann, Anne. Japanese Illustrated Handscrolls. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012.

- Willmann, Anna. Yamato-e Painting. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012.