Education for refugees, migrants and internally displaced persons

Education for refugees, migrants and internally displaced persons is the process of teaching and giving the knowledge and skills for refugees, migrants and internally displaced persons to fully participate in society. Access to education is a fundamental human right, as stated by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Education is the primary way by which displaced and marginalized migrants can lift themselves out of poverty and participate in their societies. Providing the opportunity to learn and flourish through learning can empower refugee children and adults to lead fulfilling lives, and is the means for the full realization of other human rights. Education for refugees can provide hope and long-term prospects for stability and sustainable peace for individuals, communities, countries and global society.[1]

Background

Many young people have moved from one region or country to another in search of education, work or security. Educational reforms is a powerful tool to promote inclusion and social cohesion among refugees, migrants and internally displaced persons and lift them out of poverty.[2]

“Education is a basic right” was deemed necessary in the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989 along with the Refugee Convention in 1951 (UNCHR). The purpose of education for refugees and children is to protect them from “forced recruitment into armed groups, child labor, sexual exploitation, and child marriage” (UNCHR, Education).

Education is linked and affect those who move, those who stay and those who host immigrants, refugees or other displaced populations. Studies show that internal migration mainly affects urbanizing middle income countries, such as China, where more than one in three rural children are left behind by migrating parents.[2]

International migration mainly affects high income countries, where immigrants make up at least 15% of the student population in half of schools. It also affects sending countries. More than one in four witness at least one-fifth of their skilled nationals emigrating.[2]

Displacement mainly affects low income countries, which host 10% of the global population but 20% of the global refugee population, often in their most educationally deprived areas. More than half of those forcibly displaced are underage 18.[2]

As of 2017, the number of forcibly displaced people worldwide was estimated at 68.5 million by UNHCR, including 40 million internally displaced persons, 25.4 million refugees and 3.1 million asylum-seekers. More than half of the 25.4 million refugees were children (below 18 years of age).[3] Refugee children are five times more likely to be out of school compared to their global peers. The higher the level of education, the less likely refugees are to attend. In 2017, 61% of refugee children were enrolled in primary school, compared to 92% globally.[4] 23% of refugee adolescents were enrolled at secondary level, compared to 84% globally.[4] In 2016, 1% of refugee youth were enrolled at tertiary level, compared to 34% globally.[5][6]

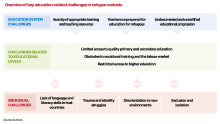

Challenges

Education affects not only migrants’ attitudes, aspirations and beliefs but also those of their hosts. Increased classroom diversity brings both challenges and opportunities to learn from other cultures and experiences. Countries are challenged to fulfil the international commitment to respect the right to education for all, from addressing the needs of those cramming into slums to living nomadically or awaiting refugee status.[2]

Teachers have to deal with multilingual classrooms and traumas affecting displaced students. Qualifications and prior learning need to be recognized to make the most of migrants’ and refugees’ skills.

Internal migration is challenging inclusion in education. Rural migrant workers constitute 21% of the Chinese population following the largest wave of internal migration in recent history. Residence permit restrictions introduced in an attempt to control the flows led the majority of migrant children in cities including Beijing to attend unauthorized migrant schools of lower quality.[2]

Barriers to immigrant education persist despite efforts towards inclusion. In South Africa, education legislation guarantees the right to education for all children regardless of migration or legal status, but immigration legislation prevents undocumented migrants from enrolling.

In the United States, anti-immigration raids led to surges in dropout among children of undocumented immigrants wary of deportation, where as an earlier policy providing deportation protection had increased secondary school completion.[2]

Although there are approximately 13% of children refugees that do not have education experience, about 76% of refugees do not have a college or industrial education, according to a survey taken in 2016 (Bundesagentur für Arbeit). Refugees drop out of schools for a variety of different reasons such as rejection by peers, lack of support from school and parents, and their lack of language proficiency. After a refugee family travels to a new country seeking asylum, the children have to “learn a new language, adapt to a new curriculum, and adapt to being in a school environment again” (Maurice Crul, Elif Keskiner, Jens Schneider, Frans Lelie and Safoura Ghaeminia) once they go to school in this new country. The language barrier in a new country is very limiting and forces the child to be in the lowest level of classes, even if they already know the information (Lina Homa).

Also, these children lack the foundation of education by not being enrolled in primary school. There are about 7.1 million refugee children of school age, but about 3.7 million of these children are not enrolled in school (UNHCR). Not only does the language barrier set children back, but so does the lack of basic education.

The constant disruptions in a refugee’s education from moving is also a large challenge to their education. Many refugee families have had to be housed in temporary shelters, but then had to “move several times in order to be housed in more permanent asylum seeker centers” (Maurice Crul, Elif Keskiner, Jens Schneider, Frans Lelie and Safoura Ghaeminia). Due to all this moving, the children would have to start at a new school everytime they moved. If the family were to go to a completely different country, the children would have to start their education all over again due to the new language barrier.

Funds

Refugee education remains underfunded. According to the Global Education Monitoring Report, Youth Report 2019, an estimated US$800 million was spent on refugee education in 2016, split roughly equally between humanitarian and development aid. That is only about one-third of the most recently estimated funding gap. If the international community employed humanitarian aid only, the share to education would have to increase tenfold to meet refugees’ education needs. Improving refugee education funding requires bridging humanitarian and development aid in line with commitments in the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants.[2]

Educational improvements

Improving educational needs can help refugees, migrants and displaced persons fully realise their potential. Non-formal education programmes can help strengthen a sense of belonging. Literacy skills support social and intercultural communication and physical, social and economic well-being, however barriers limit access to and success in adult language programmes in some countries. A 2016 survey of asylum-seekers in Germany showed that 34% were literate in a Latin script, 51% were literate in another script and 15% were illiterate. Yet they were the least likely to attend a literacy or language course.[2]

Curricula and textbooks

Appropriate education content can help citizens critically process information and promote cohesive societies. Inappropriate content can spread negative, partial, exclusive or dismissive notions of immigrants and refugees. Curricula and textbooks often include outdated depictions of migration and displacement. According to research, 81% of respondents in EU countries agreed school materials should cover ethnic diversity. By not addressing diversity in education, countries ignore its power to promote social inclusion and cohesion. A global analysis showed that social science textbook coverage of conflict prevention and resolution (i.e. discussion of domestic or international trials, truth commissions and economic reparations) was low at around 10% of texts in 2000–2011.[2]

Teacher training

Teachers affected by migration and displacement are inadequately prepared to carry out the more complex tasks, such as managing multilingual classrooms and helping children needing psychosocial support. In six European countries, half of teachers felt there was insufficient support to manage diversity in the classroom.[2] In the Syrian Arab Republic, 73% of teachers surveyed had no training on providing children with psychosocial support. Teacher recruitment and management policies often react too slowly to emerging needs. Germany needs an additional 42,000 teachers and educators, Turkey needs 80,000 teachers and Uganda needs 7,000 primary teachers to teach all current refugees.[2]

Recognition of qualifications

Recognition of qualifications and prior learning can ease entry into labour markets, especially concerning professional qualifications. If migrants and refugees lack access to employment that uses their skills, they are unlikely to develop them further. However, less than one-quarter of global migrants are covered by a bilateral qualifications recognition agreement. Existing mechanisms are often fragmented or too complex to meet immigrants’ and refugees’ needs and end up underutilized.[2]

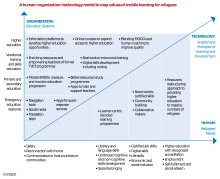

Mobile learning

Mobile learning for refugees ensures that refugees and displaced populations have access to equitable and inclusive quality education and lifelong learning opportunities through digital mobile technologies. Mobile learning plays a key role in refugees’ informal learning. The increased access that refugees have to digital mobile technologies suggests that leveraging these tools more frequently could be a source of support for education delivery, administration and support services in refugee contexts.[7]

National education systems

The inclusion of refugee children and youth in national systems provides the tools for integration of individuals and communities and can foster mutual acceptance, tolerance and respect in situations of social upheaval.[1]

In recent years, the governments have moved towards including immigrants and refugees in national education systems. Practices are being abandoned as a result of forward-looking decisions, political pragmatism and international solidarity.[2] Countries party to the 2018 Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration and the Global Compact on Refugees, which refer to education, recognize education as an opportunity. Among 21 high income countries, Australia and Canada had adopted multiculturalism in their curricula by 1980. By 2010, it had been adopted in Finland, Ireland, New Zealand and Sweden, and partly adopted in over two-thirds of the countries.[2]

Countries such as Chad, the Islamic Republic of Iran and Turkey carry out measures to ensure that Sudanese, Afghan, Syrian and other refugees attend school alongside nationals. In the 2017 Djibouti Declaration on Regional Refugee Education, seven education ministers from eastern Africa committed to the inclusion of education for refugees and returnees into sector plans by 2020.[2]

Since 2006, China has progressively revised the system, requiring local authorities to provide education to migrant children, abolishing public school fees for them and declining registered residence from access to education for migrants. In India, the 2009 Right to Education Act legally obliged local authorities to admit migrant children, while national guidelines recommend flexible admission, seasonal hostels, transport support, mobile education volunteers and improved coordination between states and districts.[2]

Sources

![]()

![]()

![]()

References

- UNESCO (2019). "Enforcing the right to education of refugees: a policy perspective" (PDF).

- UNESCO (2018). "Migration, displacement and education: building bridges, not walls; Global education monitoring report, youth report, 2019" (PDF).

- UNHCR. 2018. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2017, pp. 2-3.

- UNHCR. 2018. Turn the Tide. Refugee Education in Crisis, p. 14.

- UNHCR. 2017. Left Behind: Refugee Education in Crisis, p. 5.

- UNESCO (2019). Right to education handbook. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100305-9.

- UNESCO (2018). A Lifeline to learning: leveraging mobile technology to support education for refugees. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100262-5.