Edo

Edo (Japanese: 江戸, lit. '"bay-entrance" or "estuary"'), also romanized as Jedo, Yedo or Yeddo, is the former name of Tokyo.[2]

Edo 江戸(えど) | |

|---|---|

Former city | |

Location of the former city of Edo | |

| Coordinates: 35°41′22″N 139°41′30″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Musashi |

| Edo Castle built | 1457 |

| Capital of Japan (De facto) | 1603 |

| Renamed Tokyo | 1868 |

| Population (1721)[1] | |

| • Total | 1,000,000 |

Edo, formerly a jōkamachi (castle town) centered on Edo Castle located in Musashi Province, became the de facto capital of Japan from 1603 as the seat of the Tokugawa Shogunate. Edo grew to become one of the largest cities in the world under the Tokugawa and home to an urban culture centered on the notion of a "floating world".[1] After the Meiji Restoration in 1868 the Meiji government renamed Edo as Tokyo ("Eastern Capital") and relocated the Emperor from the historic de jure capital of Kyoto to the city.

The era of Tokugawa rule in Japan from 1603 to 1868 is known eponymously as the Edo period.

History

Tokugawa Ieyasu emerged as the paramount warlord of the Sengoku period in Japan following victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in October 1600. Tokugawa formally founded the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1603 and established his headquarters at Edo Castle, which had been constructed by Ōta Dōkan in 1457 and the town of Edo had developed as a jōkamachi around it. Edo became the center of political power and de facto capital of Japan, although the historic capital of Kyoto remained the de jure capital as the seat of the Emperor. Edo transformed from a small, little-known fishing village in Musashi Province in 1457 into the largest metropolis in the world with an estimated population of 1,000,000 by 1721.[1][3]

Edo was repeatedly devastated by fires, with the Great fire of Meireki in 1657 being the most disastrous. An estimated 100,000 people died in the fire. During the Edo period, there were about 100 fires mostly begun by accident and often quickly escalating and spreading through neighborhoods of wooden machiya which were heated with charcoal fires. Between 1600 and 1945, Edo/Tokyo was leveled every 25–50 years or so by fire, earthquakes, or war.

In 1868, the Tokugawa Shogunate was overthrown in the Meiji Restoration by supporters of Emperor Meiji and his Imperial Court in Kyoto, ending Edo's status as the de facto capital of Japan. However, the new Meiji government soon renamed Edo to Tōkyō (東京, "Eastern Capital") and became the formal capital of Japan when the Emperor moved his residence to the city:

- Keiō 4: On the 17th day of the 7th month (September 3, 1868), Edo was renamed Tokyo.[4]

- Keiō 4: On the 27th day of the 8th month (October 12, 1868), Emperor Meiji was crowned in the Shishin-den in Kyoto.[5]

- Keiō 4: On the eighth day of the ninth month (October 23, 1868), the nengō was formally changed from Keiō to Meiji and a general amnesty was granted.[5]

- Meiji 2: On the 23rd day of the 10th month (1868), the emperor went to Tokyo and Edo Castle became an imperial palace.[5]

Magistrate

Ishimaru Sadatsuga was the magistrate of Edo in 1661.[6]

Government and administration

Edo's municipal government was under the responsibility of the Rōjū, the senior officials which oversaw the entire bakufu – the government of the Tokugawa Shogunate. The Machi-bugyō (City Commissioners) were samurai officials in charge of protecting the citizens and merchants of Edo, and Kanjō-bugyō (finance commissioners) were responsible for the financial matters of the shogunate. [7]

Geography

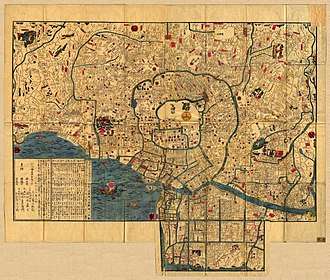

Edo was laid out as a castle town around Edo Castle. The area surrounding the castle known as Yamanote consisted largely of daimyō mansions, whose families lived in Edo as part of the sankin kōtai system; the daimyō made journeys in alternating years to Edo, and used the mansions for their entourages. It was this extensive samurai class which defined the character of Edo, particularly in contrast to the two major cities of Kyoto and Osaka neither of which were ruled by a daimyō or had a significant samurai population. Kyoto's character was defined by the Imperial Court, the court nobles, its Buddhist temples and its history; Osaka was the country's commercial center, dominated by the chōnin or the merchant class.

Areas further from the center were the domain of the chōnin (町人, "townsfolk"). The area known as Shitamachi (下町, "lower town" or "downtown"), northeast of the castle, was a center of urban culture. The ancient Buddhist temple of Sensō-ji still stands in Asakusa, marking the center of an area of traditional Shitamachi culture. Some shops in the streets near the temple have existed continuously in the same location since the Edo period.

The Sumida River, then called the Great River (大川, Ōkawa), ran along the eastern edge of the city. The shogunate's official rice-storage warehouses,[8] other official buildings and some of the city's best-known restaurants were located here.

The "Japan Bridge" (日本橋, Nihon-bashi) marked the center of the city's commercial center, an area also known as Kuramae (蔵前, "in front of the storehouses"). Fishermen, craftsmen and other producers and retailers operated here. Shippers managed ships known as tarubune to and from Osaka and other cities, bringing goods into the city or transferring them from sea routes to river barges or land routes such as the Tōkaidō. This area remains the center of Tokyo's financial and business district.

The northeastern corner of the city was considered a dangerous direction in traditional onmyōdō (cosmology), and is protected from evil by a number of temples including Sensō-ji and Kan'ei-ji. Beyond this were the districts of the eta or outcasts, who performed "unclean" work and were separated from the main parts of the city. A path and a canal, a short distance north of the eta districts, extended west from the riverbank leading along the northern edge of the city to the Yoshiwara pleasure districts. Previously located near Ningyocho, the districts were rebuilt in this more-remote location after the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657, as the city expanded.

Gallery

See Tokyo for photographs of the modern city.

See also

- Edo period

- Edo society

- Fires in Edo

- 1703 Genroku earthquake

- Edokko (native of Edo)

- History of Tokyo

- Iki (a Japanese aesthetic ideal)

- Asakusa

Notes

- Sansom, George. A History of Japan: 1615–1867, p. 114.

- US Department of State. (1906). A digest of international law as embodied in diplomatic discussions, treaties and other international agreements (John Bassett Moore, ed.), Vol. 5, p. 759; excerpt, "The Mikado, on assuming the exercise of power at Yedo, changed the name of the city to Tokio".

- Gordon, Andrew. (2003). A Modern History of Japan from Tokugawa Times to the Present, p. 23.

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1956). Kyoto: the Old Capital, 794–1869, p. 327.

- Ponsonby-Fane, p. 328.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (1911): "Japan: Commerce in Tokugawa Times," p. 201.

- Deal, William E. (2007). Handbook to life in medieval and early modern Japan. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195331265.

- Taxes, and samurai stipends, were paid not in coin, but in rice. See koku.

References

- Forbes, Andrew; Henley, David (2014). 100 Famous Views of Edo. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00HR3RHUY

- Gordon, Andrew. (2003). A Modern History of Japan from Tokugawa Times to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511060-9/ISBN 978-0-19-511060-9 (cloth); ISBN 0-19-511061-7/ISBN 978-0-19-511061-6.

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1956). Kyoto: the Old Capital, 794–1869. Kyoto: Ponsonby Memorial Society.

- Sansom, George. (1963). A History of Japan: 1615–1867. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0527-5/ISBN 978-0-8047-0527-1.

- Akira Naito (Author), Kazuo Hozumi. Edo, the City that Became Tokyo: An Illustrated History. Kodansha International, Tokyo (2003). ISBN 4-7700-2757-5

- Alternate spelling from 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edo. |

- A Trip to Old Edo

- (in Japanese) Fukagawa Edo Museum