Echo chamber (media)

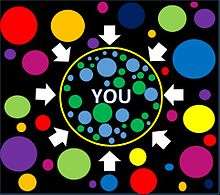

In news media, an echo chamber is a metaphorical description of a situation in which beliefs are amplified or reinforced by communication and repetition inside a closed system and insulates them from rebuttal.[1] By visiting an "echo chamber", people are able to seek out information that reinforces their existing views, potentially as an unconscious exercise of confirmation bias. This may increase social and political polarization and extremism.[2] The term is a metaphor based on the acoustic echo chamber, where sounds reverberate in a hollow enclosure. Another emerging term for this echoing and homogenizing effect on the Internet within social communities, such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Reddit, etc; is cultural tribalism.[3] Many scholars note the effects that echo chambers can potentially have on citizen's stance and viewpoints, more specifically what implications this effect will have on politics. However, there are counterarguments with supporting evidence that suggest the effects of echo chambers are significantly lowered than assumed and suggested.[4]

Concept

The Internet has expanded the variety and amount of accessible political information. On the positive side, this may create a more pluralistic form of public debate; on the negative side, greater access to information may lead to selective exposure to ideologically supportive channels.[2] In an extreme "echo chamber", one purveyor of information will make a claim, which many like-minded people then repeat, overhear, and repeat again (often in an exaggerated or otherwise distorted form)[5] until most people assume that some extreme variation of the story is true.[6]

The echo chamber effect occurs online due to a harmonious group of people amalgamating and developing tunnel vision. Participants in online discussions may find their opinions constantly echoed back to them, which reinforces their individual belief systems due to the declining exposure to other's opinions.[7] Their individual belief systems are what culminate into a confirmation bias regarding a variety of subjects. When an individual wants something to be true, they often will only gather information that supports their existing beliefs and disregard any statements they find that are contradictory or speak negatively upon their beliefs.[8] Individuals who participate in echo chambers often do so because they feel more confident that their opinions will be more readily accepted by others in the echo chamber.[9] This happens because the Internet has provided access to a wide range of readily available information. People are receiving their news online more rapidly through less traditional sources, such as Facebook, Google, and Twitter. These and many other social platforms and online media outlets have established personalized algorithms intended to cater specific information to individuals’ online feeds. This method of curating content has replaced the function of the traditional news editor.[10] The mediated spread of information through online networks causes a risk of an algorithmic filter bubble, leading to concern regarding how the effects of echo chambers on the internet promote the division of online interaction. [11]

It is important to note that members of an echo chamber are not fully responsible for their convictions. Once part of an echo chamber, an individual might adhere to seemingly acceptable epistemic practices and still be further misled. Many individuals may be stuck in echo chambers due to factors existing outside of their control, such as being raised in one.[12]

Furthermore, the function of an echo chamber does not entail eroding a member's interest in truth; it focuses upon manipulating their credibility levels so that fundamentally different establishments and institutions will be considered proper sources of authority.[13]

Echo Chambers vs Epistemic Bubbles

In recent years, closed epistemic networks have increasingly been held responsible for the era of post-truth and fake news.[14] However, the media frequently conflates two distinct concepts of social epistemology: echo chambers and epistemic bubbles.[13]

An epistemic bubble is an informational network in which important sources have been excluded by omission, perhaps unintentionally. It is an impaired epistemic framework which lacks strong connectivity.[15] Members within epistemic bubbles are unaware of significant information and reasoning.

On the other hand, an echo chamber is an epistemic construct in which voices are actively excluded and discredited. It does not suffer from a lack in connectivity; rather it depends on a manipulation of trust by methodically discrediting all outside sources.[16] According to research conducted by the University of Pennsylvania, members of echo chambers become dependent on the sources within the chamber and highly resistant to any external sources.[17]

An important distinction exists in the strength of the respective epistemic structures. Epistemic bubbles are not particularly robust. Relevant information has merely been left out, not discredited.[18] One can ‘pop’ an epistemic bubble by exposing a member to the information and sources that they have been missing.[12]

Echo chambers, however, are incredibly strong. By creating pre-emptive distrust between members and non-members, insiders will be insulated from the validity of counter-evidence and will continue to reinforce the chamber in the form of a closed loop.[16] Outside voices are heard, but dismissed.

As such, the two concepts are fundamentally distinct and cannot be utilized interchangeably. However, one must note that this distinction is conceptual in nature, and an epistemic community can exercise multiple methods of exclusion to varying extents.

Similar concepts

A filter bubble – a term coined by internet activist Eli Pariser – is a state of intellectual isolation that allegedly can result from personalized searches when a website algorithm selectively guesses what information a user would like to see based on information about the user, such as location, past click-behavior and search history. As a result, users become separated from information that disagrees with their viewpoints, effectively isolating them in their own cultural or ideological bubbles. The choices made by these algorithms are not transparent.

Homophily is the tendency of individuals to associate and bond with similar others, as in the proverb "birds of a feather flock together". The presence of homophily has been detected in a vast array of network studies.

Both echo chambers and filter bubbles relate to the ways individuals are exposed to content devoid of clashing opinions, and colloquially might be used interchangeably. However, echo chamber refers to the overall phenomenon by which individuals are exposed only to information from like-minded individuals, while filter bubbles are a result of algorithms that choose content based on previous online behavior, as with search histories or online shopping activity.[19] It is equally important to understand that although similar, Homophily and echo chambers are not the same either.

Implications of Echo Chambers

Online Communities

Online social communities become fragmented by echo chambers when like-minded people group together and members hear arguments in one specific direction with no counter argument addressed. In certain online platforms, such as Twitter, echo chambers are more likely to be found when the topic is more political in nature compared to topics that are seen as more neutral.[20] Social networking communities are communities that are considered to be some of the most powerful reinforcements of rumors[21] due to the trust in the evidence supplied by their own social group and peers, over the information circulating the news.[22] In addition to this, the reduction of fear that users can enjoy through projecting their views on the internet versus face-to-face allows for further engagement in agreement with their peers.[23]

This can create significant barriers to critical discourse within an online medium. Social discussion and sharing can potentially suffer when people have a narrow information base and don't reach outside their network. Essentially, the filter bubble can distort our very own realities that we thought could not be altered by outside sources. The Farnam Street academic blog explains that the filter bubble can have a bigger impact on us than we think. It can create echo chambers that leads us to believe that what you are seeing through ads is the only opinion or perspective that is right.[24]

Offline Communities

Many offline communities are also segregated by political beliefs and cultural views. The echo chamber effect may prevent individuals from noticing changes in language and culture involving groups other than their own. Online echo chambers can sometimes influence an individual's willingness to participate in similar discussions offline. A 2016 study found that “Twitter users who felt their audience on Twitter agreed with their opinion were more willing to speak out on that issue in the workplace”.[9]

Examples

Ideological echo chambers have existed in many forms, for centuries. Some examples of this include:

- The McMartin preschool trial coverage was criticized by David Shaw in his 1990 Pulitzer Prize winning articles, "None of these charges was ultimately proved, but the media largely acted in a pack, as it so often does on big events, and reporters' stories, in print and on the air, fed on one another, creating an echo chamber of horrors."[25] Shaw stated that this case "exposed basic flaws" in news organizations such as "Laziness. Superficiality. Cozy relationships" and "a frantic search to be first with the latest shocking allegation". His regard to mention "Reporters and editors often abandoned" journalistic principles of "fairness and skepticism." And "frequently plunged into hysteria, sensationalism and what one editor calls 'a lynch mob syndrome'" further supports the echo chamber effect and how it alters the coverage of specific types of media.

- The conservative radio host, Rush Limbaugh, and his radio show have been categorized as an echo chamber in the first empirical study concerning echo chambers by researchers Kathleen Hall Jamieson and Frank Capella in their book: Echo Chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the Conservative Media Establishment (2010)[26]

- The Clinton-Lewinsky scandal reporting was chronicled in Time Magazine's 16 February 1998 "Trial by Leaks" cover story[27] "The Press And The Dress: The anatomy of a salacious leak, and how it ricocheted around the walls of the media echo chamber" by Adam Cohen.[28] This case was also reviewed in depth by the Project for Excellence in Journalism in "The Clinton/Lewinsky Story: How Accurate? How Fair?"[29]

- A New Statesman essay argued that echo chambers were linked to the UK Brexit referendum.[30]

- The subreddit /r/incels and other online incel communities have also been described as echo chambers.[31][32][33]

- Discussion concerning Opioid drugs and whether or not they should be considered suitable for long-term pain maintenance[34]

- Climate change discussions and beliefs on the research presented that suggest the changes in climate currently present are due to human behavior.[23] However, there is a differing stance that seems to have a growing echo chamber on specific media outlets.

However, since the creation of the internet, scholars have been curious to see the changes in political communication.[35] Due to the new changes in information technology and how it's managed, understanding opposing perspectives and reaching a common ground in a democracy has been up for debate.[36] The effects seen from the echo chamber effect has largely been cited to occur in politics as the effects of this fragmenting media exposure method as described in these examples:

- Twitter, as a platform is continuously described as an aid in hindering constructive discussions that would be possible of aiding to these differing, yet coexisting stances due to the interaction that takes place majority of the time reinforcing their similar perspectives.[37] The 2016 presidential election in the United States triggered a stream of discourse about the echo chamber effect.[38] Both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton used this platform to their advantage incorporating it into their own campaigning.[39] Constituents were more likely to absorb information about topics such as gun control and immigration that aligned with their preexisting beliefs, as they were more likely to view information they already agreed with.[40]

- Facebook was a reflection of the echo chamber effect during the 2016 presidential election as well due to the more likeliness to suggest posts that are congruent with your standpoints; therefore there was mainly repetition of already stable standpoints instead of a diversity of opinions. Journalists argue that diversity of opinion is necessary for true democracy as it facilitates communication, and echo chambers, like those occurring in Facebook, inhibited this.[38] Some believed echo chambers played a big part in the success of Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential elections.[41]

Countermeasures

From Media Companies

Some companies have also made efforts in combating the effects of an echo chamber on an algorithmic approach. A high-profile example of this is the changes Facebook made to its “Trending” page, which is an on-site news source for its users. Facebook modified their “Trending” page by transitioning from displaying a single news source to multiple news sources for a topic or event.[42] The intended purpose of this was to expand the breadth of news sources for any given headline, and therefore expose readers to a variety of viewpoints. There are startups building apps with the mission of encouraging users to open their echo chambers. UnFound.news offers an AI(Artifical Intelligence) curated news app to readers presenting them news from diverse and distinct perspectives, helping them form rational and informed opinion rather than succumbing to their own biases. It also nudges the readers to read different perspectives if their reading pattern is biased towards one side/ideology.[43][44] Another example is a beta feature on BuzzFeed News, called “Outside Your Bubble".[45] This experiment adds a module at the bottom of BuzzFeed News articles to show reactions from various platforms, like Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit. This concept aims to bring transparency and prevent biased conversations diversifying the viewpoints their readers are exposed to.[46]

See also

- Big lie

- Circular source

- Communal reinforcement

- Confirmation bias

- Disinformation

- Epistemic closure

- False consensus effect

- Filter bubble

- Google's Ideological Echo Chamber

- Groupthink

- Idola specus

- Information silo

- Manufacturing Consent

- Media circus

- Opinion corridor

- Party line

- Peer review

- Positive feedback

- Red herring

- Reinforcement theory

- Safe-space

- Selective exposure theory

- Spiral of silence

- Splinternet

- stereotype

- Tribe (Internet)

References

- "echo-chamber noun - Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes | Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com". www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Retrieved 2020-04-25.

- Barberá, Pablo, et al. "Tweeting from left to right: Is online political communication more than an echo chamber?." Psychological science 26.10 (2015): 1531-1542.

- Dwyer, Paul. "Building Trust with Corporate Blogs" (PDF). Texas A&M University: 7. Retrieved 2008-03-06. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gentzkow, Matthew; Shapiro, Jesse M. (November 2011). "Ideological Segregation Online and Offline *". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 126 (4): 1799–1839. doi:10.1093/qje/qjr044. ISSN 0033-5533.

- Parry, Robert (2006-12-28). "The GOP's $3 Bn Propaganda Organ". The Baltimore Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- "SourceWatch entry on media "Echo Chamber" effect". SourceWatch. 2006-10-22. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- Mutz, Diana C. (2006). Hearing the Other Side. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511617201. ISBN 978-0-511-61720-1.

- Heshmat, Shahram (2015-04-23). "What Is Confirmation Bias?". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2020-04-25.

- Hampton, Keith N.; Shin, Inyoung; Lu, Weixu (2017-07-03). "Social media and political discussion: when online presence silences offline conversation". Information, Communication & Society. 20 (7): 1090–1107. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2016.1218526. ISSN 1369-118X.

- Hosanagar, Kartik (2016-11-25). "Blame the Echo Chamber on Facebook. But Blame Yourself, Too". Wired.com. Retrieved 2017-09-24.

- Ulen, Thomas S. (2001). "Democracy and the Internet: Cass R. Sunstein, Republic.Com. Princeton, NJ. Princeton University Press. Pp. 224. 2001". SSRN Working Paper Series. doi:10.2139/ssrn.286293. ISSN 1556-5068.

- Nguyen, C. Thi (June 2020). "ECHO CHAMBERS AND EPISTEMIC BUBBLES". Episteme. 17 (2): 141–161. doi:10.1017/epi.2018.32. ISSN 1742-3600.

- "The Reason Your Feed Became An Echo Chamber — And What To Do About It". NPR.org. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- Robson, David. "The myth of the online echo chamber". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- Magnani, Lorenzo; Bertolotti, Tommaso (2011). "Cognitive Bubbles and Firewalls: Epistemic Immunizations in Human Reasoning". Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. 33 (33). ISSN 1069-7977.

- ""Echo chambers," polarization, and the increasing tension between the (social) reality of expertise and the (cultural) suspicion of authority". uva.theopenscholar.com. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- ""Echo Chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the Conservative Media Establishment." Oxford University Press, 2010. | Annenberg School for Communication". www.asc.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- "Americans, Politics and Social Media". Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- Bakshy, Eytan; Messing, Solomon; Adamic, Lada A. (2015-06-05). "Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook". Science. 348 (6239): 1130–1132. Bibcode:2015Sci...348.1130B. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1160. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25953820.

- Barberá, Pablo; Jost, John T.; Nagler, Jonathan; Tucker, Joshua A.; Bonneau, Richard (2015-08-21). "Tweeting From Left to Right". Psychological Science. 26 (10): 1531–1542. doi:10.1177/0956797615594620. PMID 26297377.

- DiFonzo, Nicholas (2008-09-11). The Watercooler Effect: An Indispensable Guide to Understanding and Harnessing the Power of Rumors. Penguin Books. ISBN 9781440638633. Retrieved 2017-09-24.

- DiFonzo, Nicholas (2011-04-21). "The Echo-Chamber Effect". The New York Times. Retrieved 2017-09-24.

- Walter, Stefanie; Brüggemann, Michael; Engesser, Sven (2017-12-21). "Echo Chambers of Denial: Explaining User Comments on Climate Change". Environmental Communication. 12 (2): 204–217. doi:10.1080/17524032.2017.1394893. ISSN 1752-4032.

- Parrish, Shane (2017-07-31). "How Filter Bubbles Distort Reality: Everything You Need to Know". Farnam Street.

- SHAW, DAVID (19 January 1990). "COLUMN ONE : NEWS ANALYSIS : Where Was Skepticism in Media? : Pack journalism and hysteria marked early coverage of the McMartin case. Few journalists stopped to question the believability of the prosecution's charges". Los Angeles Times.

- Jamieson, Kathleen; Cappella, Joseph (2008-01-01). Echo Chamber: Rush Limbaugh and the Conservative Media Establishment. ISBN 978-0-19-536682-2.

- "TIME Magazine -- U.S. Edition -- February 16, 1998 Vol. 151 No. 6". 151 (6). February 16, 1998.

- Cohen, Adam (16 February 1998). "The Press And The Dress". Time.

- "The Clinton/Lewinsky Story: How Accurate? How Fair?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- Chater, James. "What the EU referendum result teaches us about the dangers of the echo chamber". NewStatesman.

- Taub, Amanda (9 May 2018). "On Social Media's Fringes, Growing Extremism Targets Women". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- Beauchamp, Zack (25 April 2018). "Incel, the misogynist ideology that inspired the deadly Toronto attack, explained". Vox. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- "The government shouldn't let potential dangerous people go unnoticed online".

- "Pro-painkiller echo chamber shaped policy amid drug epidemic". Center for Public Integrity. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- NEUMAN, W. RUSSELL (July 1996). "Political Communications Infrastructure". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 546 (1): 9–21. doi:10.1177/0002716296546001002. ISSN 0002-7162.

- Mutz, Diana C. (March 2001). "Facilitating Communication across Lines of Political Difference: The Role of Mass Media". American Political Science Review. 95 (1): 97–114. doi:10.1017/s0003055401000223. ISSN 0003-0554.

- Colleoni, Elanor; Rozza, Alessandro; Arvidsson, Adam (April 2014). "Echo Chamber or Public Sphere? Predicting Political Orientation and Measuring Political Homophily in Twitter Using Big Data: Political Homophily on Twitter". Journal of Communication. 64 (2): 317–332. doi:10.1111/jcom.12084. hdl:10281/66011.

- El-Bermawy, Mostafa (2016-11-18). "Your Filter Bubble is Destroying Democracy". Wired.

- Hamidaddin, Abdullah (2019-10-24), Tweeted Heresies, Oxford University Press, pp. 65–103, doi:10.1093/oso/9780190062583.003.0004, ISBN 978-0-19-006258-3 Missing or empty

|title=(help);|chapter=ignored (help) - Difonzo, Nicolas (22 April 2011). "The Echo Chamber Effect". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- Hooton, Christopher (10 November 2016). "Your social media echo chamber is the reason Donald Trump ended up being voted President". The Independent. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- "Continuing Our Updates to Trending". About Facebook. 2017-01-25. Retrieved 2020-04-25.

- "AI meets News". unfound.news. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- "Echo chambers, algorithms and start-ups". LiveMint. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- "Outside Your Bubble". BuzzFeed. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- Smith, Ben (February 17, 2017). "Helping You See Outside Your Bubble". BuzzFeed.

Further reading

- Philip McRae, "Forecasting the Future Over Three Horizons of Change ", ATA Magazine, May 21, 2010.

- John Scruggs, "The "Echo Chamber" Approach to Advocacy", Philip Morris, Bates No. 2078707451/7452, December 18, 1998.

- The Hudson Institute's Bradley Center for Philanthropy and Civic Renewal wonder if they "got it, well, Right".

- "Buying a Movement: Right-Wing Foundations and American Politics," (Washington, DC: People for the American Way, 1996). Or download a PDF version of the full report.

- Dan Morgan, "Think Tanks: Corporations' Quiet Weapon," Washington Post, January 29, 2000, p. A1.

- Jeff Gerth and Sheryl Gay Stolberg, "Drug Industry Has Ties to Groups With Many Different Voices", New York Times, October 5, 2000.

- Robert Kuttner, "Philanthropy and Movements," The American Prospect, July 2, 2002.

- Robert W. Hahn, "The False Promise of 'Full Disclosure'," Policy Review, Hoover Institution, October 2002.

- David Brock, Blinded by the Right: The Conscience of an Ex-Conservative (New York, NY: Three Rivers Press, 2002).

- Jeff Chester, "A Present for Murdoch", The Nation, December 2003: "From 1999 to 2002, his company spent almost $10 million on its lobbying operations. It has already poured $200,000 in contributions into the 2004 election, having donated nearly $1.8 million during the 2000 and 2002 campaigns."

- Jim Lobe for Asia Times: "the structure's most remarkable characteristics are how few people it includes and how adept they have been in creating new institutions and front groups that act as a vast echo chamber for one another and for the media"

- Valdis Krebs, "Divided We Stand," Political Echo Chambers

- Jonathan S. Landay and Tish Wells, "Iraqi exile group fed false information to news media", Knight Ridder, March 15, 2004.

- R.G. Keen: The Technology of Oil Can Delays

- Echo chamber at SourceWatch