Droughts and famines in Russia and the Soviet Union

Throughout Russian history famines and droughts have been a common feature, often resulting in humanitarian crises traceable to political or economic instability, poor policy, environmental issues and war. Droughts and famines in Russian Empire tended to occur fairly regularly, with famine occurring every 10–13 years and droughts every five to seven years. Golubev and Dronin distinguish three types of drought according to productive areas vulnerable to droughts: Central (the Volga basin, North Caucasus and the Central Chernozem Region), Southern (Volga and Volga-Vyatka area, the Ural region, and Ukraine), and Eastern (steppe and forest-steppe belts in Western and Eastern Siberia, and Kazakhstan).[1]

Pre-1900 droughts and famines

In the 17th century, Russia experienced the famine of 1601–1603, as a proportion of the population, believed to be its worst as it may have killed 2 million people (1/3 of the population). ( 5 million people estimated to have died in 1920-22 famine). Major famines include the Great Famine of 1315–17, which affected much of Europe including part of Russia[2][3] as well as the Baltic states.[4] The Nikonian chronicle, written between 1127 and 1303, recorded no less than eleven famine years during that period.[5] One of the most serious crises before 1900 was the famine of 1891–92, which killed between 375,000 and 500,000 people, mainly due to famine-related diseases. Causes included a large Autumn drought resulting in crop failures. Attempts by the government to alleviate the situation generally failed which may have contributed to a lack of faith in the Czarist regime and later political instability.[5][6]

List of post-1900 droughts and famines

The Golubev and Dronin report gives the following table of the major droughts in Russia between 1900 and 2000.[1]

- Central: 1920, 1924, 1936, 1946, 1972, 1979, 1981, 1984.

- Southern: 1901, 1906, 1921, 1939, 1948, 1951, 1957, 1975, 1995.

- Eastern: 1911, 1931, 1963, 1965, 1991.

1900s

The failed Revolution of 1905 likely{{Weasel}} distorted output and restricted food availability.{{cn}}

1910s

During the Russian Revolution and following civil war there was a decline in total agricultural output. Measured in millions of tons the 1920 grain harvest was only 46.1, compared to 80.1 in 1913. By 1926 it had almost returned to pre-war levels reaching 76.8.[7]

1920s

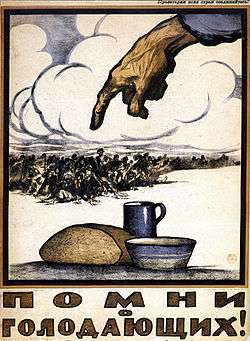

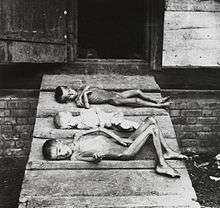

The early 1920s saw a series of famines. The first famine in the USSR happened in 1921–1923 and garnered wide international attention. The most affected area being the Southeastern areas of European Russia (including Volga region, especially national republics of Idel-Ural, see 1921–22 famine in Tatarstan) and Ukraine. An estimated 16 million people may have been affected and up to 5 million died.[8][9] Fridtjof Nansen was honored with the 1922 Nobel Peace Prize, in part for his work as High Commissioner for Relief In Russia.[10] Other organizations that helped to combat the Soviet famine were International Save the Children Union and the International Committee of the Red Cross.[11]

When the Russian famine of 1921 broke out, the American Relief Administration's director in Europe, Walter Lyman Brown, began negotiating with Soviet deputy People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Maxim Litvinov, in Riga, Latvia. An agreement was reached on August 21, 1921, and an additional implementation agreement was signed by Brown and People's Commisar for Foreign Trade Leonid Krasin on December 30, 1921. The U.S. Congress appropriated $20,000,000 for relief under the Russian Famine Relief Act of late 1921.

At its peak, the ARA employed 300 Americans, more than 120,000 Russians and fed 10.5 million people daily. Its Russian operations were headed by Col. William N. Haskell. The Medical Division of the ARA functioned from November 1921 to June 1923 and helped overcome the typhus epidemic then ravaging Russia. The ARA's famine relief operations ran in parallel with much smaller Mennonite, Jewish and Quaker famine relief operations in Russia.[12][13]

The ARA's operations in Russia were shut down on June 15, 1923, after it was discovered that Russia renewed the export of grain.[14]

1930s

Soviet famine of 1932–1933

The second major Soviet famine happened during the initial push for collectivization during the 30s. Major causes include the 1932–33 confiscations of grain and other food by the Soviet authorities which contributed to the famine and affected more than forty million people, especially in the south on the Don and Kuban areas and in Ukraine, where by various estimates millions starved to death or died due to famine related illness (the event known as Holodomor).[15] The famine was perhaps most severe in Kazakhstan where the semi-nomadic pastoralists' traditional way of life was most disturbed by Soviet agricultural ambitions.[16]

There is still debate over whether or not Holodomor was a massive failure of policy or a deliberate act of genocide.[17] Robert Conquest held the view that the famine was not intentionally inflicted by Stalin, but "with resulting famine imminent, he could have prevented it, but put “Soviet interest” other than feeding the starving first—thus consciously abetting it".[18] Michael Ellman's analysis of the famine found that "there is some evidence that in 1930-33 ... Stalin also used starvation in his war against the peasants", which he calls a "conscious policy of starvation", but concludes that there were several factors, primarily focusing on the leadership's culpability in continuing to prioritize collectivization and industrialization over preventing mass death[16] , due to their Leninist stance of regarding starvation "as a necessary cost of the progressive policies of industrialisation and the building of socialism", and thus did not "perceive the famine as a humanitarian catastrophe requiring a major effort to relieve distress and hence made only limited relief efforts."[19]

Similarly, Mark Tauger concludes that the famine was not intentional genocide but the result of failed economic policy:

Although the low 1932 harvest may have been a mitigating circumstance, the regime was still responsible for the deprivation and suffering of the Soviet population in the early 1930s. The data presented here provide a more precise measure of the consequences of collectivization and forced industrialization than has previously been available; if anything, these data show that the effects of those policies were worse than has been assumed. They also, however, indicate that the famine was real, the result of a failure of economic policy, of the "revolution from above," rather than of a "successful" nationality policy against Ukrainians or other ethnic groups.[20]

There is also the controversial argument by Douglas Tottle, a Canadian Communist Party member, that the famine was significantly worsened by the actions of the kulaks, a class of peasants who had become wealthy after the Stolypin reform, many of whom burned their crops and killed their livestock rather than give their lands and livestock over to collectivization.[21] Tottle's book has been severely criticised. David Patrikarakos, writing in the New Republic, called it "revisionism" and compared it to Soviet propaganda.[22]. Former Harvard professor, Frank Sysyn, states that "the book was likely compiled in the Soviet Union" and Soviet-sponsored as a response to the release of Robert Conquest's book The Harvest of Sorrow which argues that the famine was man-made.[23]

Demographic impact

—Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin[24]

The demographic impact of the famine of 1932–1933 was multifold. In addition to direct and indirect deaths associated with the famine, there were significant internal migrations of Soviet citizens, often fleeing famine-ridden regions. A sudden decline in birthrates permanently "scarred" the long-term population growth of the Soviet Union in a way similar to, although not as severe, as that of World War 2.

Estimates of Soviet deaths attributable to the 1932–1933 famine vary wildly, but are typically given in the range of millions.[25][26][27] Vallin et al. estimated that the disasters of the decade culminated in a dramatic fall in fertility and a rise in mortality. Their estimates suggest that total losses can be put at about 4.6 million, 0.9 million of which was due to forced migration, 1 million to a deficit in births, and 2.6 million to exceptional mortality.[28] The long-term demographic consequences of collectivization and the Second World War meant that the Soviet Union's 1989 population was 288 million rather than 315 million, 9% lower than it otherwise would have been.[29] In addition to the deaths, the famine resulted in massive population movements, as about 300,000 Kazakh nomads fled to China, Iran, Mongolia and Afghanistan during the famine.[30][31]

Although famines were taking place in various parts of the USSR in 1932–1933, for example in Kazakhstan,[32] parts of Russia and the Volga German Republic,[33] the name Holodomor is specifically applied to the events that took place in territories populated by Ukrainians and also North Caucasian Kazakhs.

Legacy

The legacy of Holodomor remains a sensitive and controversial issue in contemporary Ukraine where it is regarded as an act of genocide by the government and is generally remembered as one of the greatest tragedies in the nation's history.[34][35][36] The issue of Holodomor being an intentional act of genocide or not has often been a subject of dispute between the Russian Federation and Ukrainian government. The modern Russian government has generally attempted to disassociate and downplay any links between itself and the famine.[37][38][39]

1940s

During the Siege of Leningrad by Nazi Germany, as many as one million people died while many more went hungry or starved but survived. Germans tried to starve out Leningrad in order to break its resistance. Starvation was one of the primary causes of death as the food supply was cut off and strict rationing was enforced. Animals in the city were slaughtered and eaten. Instances of cannibalism were reported.[40][41]

The last major famine in the USSR happened mainly in 1947 as a cumulative effect of consequences of collectivization, war damage, the severe drought in 1946 in over 50 percent of the grain-productive zone of the country and government social policy and mismanagement of grain reserves. The regions primarily affected were Transnistria in Moldova and South Eastern Ukraine.[42][43] Between 100,000 and one million people may have perished.[44]

1947–1991

There were no famines after 1947. The drought of 1963 caused panic slaughtering of livestock, but there was no risk of famine. After that year the Soviet Union started importing feed grains for its livestock in increasing amounts.[45]

Post-Soviet Russia

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, there have been occasional issues with hunger and food security in Russia.[46] In 1992 there was a notable decline in calorie intake within the Russian Federation.[47] Both Russia and Ukraine have been subject to a series of severe droughts from July 2010 to 2015.[48] The 2010 drought saw wheat production fall by 20% in Russia and subsequently resulted in a temporary ban on grain exports.[49]

See also

- 1921–22 famine in Tatarstan

- Famine in Kazakhstan of 1932–33

- Holodomor

- Hunger Plan

- List of famines

- Russian famine of 1921

- Siege of Leningrad

- Soviet famine of 1932–33

- Soviet famine of 1946–47

- Trofim Lysenko

Notable victims

References

Footnotes

- Golubev, Genady; Nikolai Dronin (February 2004). "Geography of Droughts and Food Problems in Russia (1900–2000), Report No. A 0401" (PDF). Center for Environmental Systems Research, University of Kassel. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- Smitha, Frank E. "Russia to 1700". fsmitha.com. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- Lucas, Henry S. "The great European famine of 1315, 1316, and 1317." Speculum 5.4 (1930): 343-377.

- Jordan, William C. (1996). The Great Famine. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 1-4008-0417-5.

- "The Russian Famine of 1891–92". www.loyno.edu. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- "The History of International Humanitarian Assistance: Notes on Developments in 19th and 20th centuries". Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI). Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- Nove, Alec (1992). An Economic History of the USSR 1917–1991. Penguin Books. pp. 88–89.

Nove notes that the harvest in 1913 was during an "extremely favorable year" indicating a somewhat larger than expected crop.

- "WGBH American Experience . The Great Famine | PBS". American Experience. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- HAVEN, CYNTHIA (April 4, 2011). "How the U.S. saved a starving Soviet Russia: PBS film highlights Stanford scholar's research on the 1921–23 famine | Stanford News Release". news.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-21.

- "Fridtjof Nansen – Facts". www.nobelprize.org. 2014. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- "Famine in Russia, 1921–1922". www2.warwick.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-04-21.

- See Lance Yoder's "Historical Sketch" in the online Mennonite Central Committee Photograph Collection Archived 2012-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- See David McFadden et al., Constructive Spirit: Quakers in Revolutionary Russia, 2004

- Charles M. Edmondson, "An Inquiry into the Termination of Soviet Famine Relief Programmes and the Renewal of Grain Export, 1922–23", Soviet Studies, Vol. 33, No. 3 (1981), pp. 370–385

- Fawkes, Helen (November 24, 2006). "Legacy of famine divides Ukraine". BBC News. Kiev. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- Gráda, C. Ó. (2010). Famine: a short history. Princeton University Press.

- "Genocide or "A Vast Tragedy"? | Literary Review of Canada". Literary Review of Canada. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- Davies, R. W. and S. G. Wheatcroft (2004). The Years Of Hunger. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 441 note 145.

- Ellman, Michael (2005). "The Role of Leadership Perceptions and of Intent in the Soviet Famine of 1931 – 1934" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 57 (6): 823–841. doi:10.1080/09668130500199392.

- Tauger, Mark B. "The 1932 Harvest and the Famine of 1933." Slavic Review 50.1 (1991): 89.

- Tottle, Douglas "Fraud, Famine and Fascism: The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard." Progress Books (1987)

- Patrikarakos, David (2017-11-21). "Why Stalin Starved Ukraine". New Republic.

- Sysyn, Frank (2015). "Thirty Years of Research on the Holodomor: A Balance Sheet" (PDF). East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies. 2: 7.

- Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. p. 53.

- "Ukraine – The famine of 1932–33 | history – geography". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- "The Great Famine – History Learning Site". History Learning Site. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- "The History Place – Genocide in the 20th Century: Stalin's Forced Famine 1932–33". www.historyplace.com. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- Vallin, Jacques; Meslé, France; Adamets, Serguei; Pyrozhkov, Serhii (2002). A New Estimate of Ukrainian Population Losses during the Crises of the 1930s and 1940s.

- Allen, Robert C (2003). Farm to Factory: A Reinterpretation of the Soviet Industrial Revolution. Princeton University Press. pp. 117–120.

The Second World War had greater effect on the size of the population. Figure 6.5 simulates the population without the excess mortality of the war and, in addition, without the reduction in fertility during and after the war. Eliminating the wartime mortality raises the 1989 population to 329 million, and eliminating the shortfall in fertility raises it by a further 34 million to 363 million. The fertility effect (34 million) was almost as large as the mortality effect (41 million). World War II cut the Soviet population by 21 percent. Figure 6.7 shows the results of a combined simulation in which the adverse fertility and mortality effects of the war and collectivization are removed from Soviet demographic history. The simulation shows how the population would have grown if it were subject to the "normal fertility" and mortality rates. The 1989 population under this simulation would have been 394 million instead of the 288 million actually alive. The impact of collectivization and the Second World War was to reduce the 1989 population of the Soviet Union by 27%.

- Kokaisl, Petr. "Soviet collectivisation and its specific focus on central Asia." AGRIS on-line Papers in Economics and Informatics 5.4 (2013): 121.

- Thomas, Alun. Kazakh Nomads and the New Soviet State, 1919-1934. Diss. University of Sheffield, 2015.

- Ertz, Simon (2005). "The Kazakh Catastrophe and Stalin's Order of Priorities, 1929–1933: Evidence from the Soviet Secret Archives" (PDF). Zhe : Stanford's Student Journal of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies. Stanford University. Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies. 1 (Spring). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2006.

- Sinner, Samuel D. (August 28, 2005). "The German-Russian Genocide: Remembrance in the 21st Century". lib.ndsu.nodak.edu. Archived from the original on July 8, 2008.

- Kappeler, Andreas (2014). "Ukraine and Russia: Legacies of the imperial past and competing memories". Journal of Eurasian Studies.

- Motyl, Alexander (2010). "Deleting the Holodomor: Ukraine unmakes itself". World Affairs.

- Kupfer, Matthew, and Thomas de Waal. "Crying Genocide: Use and Abuse of Political Rhetoric in Russia and Ukraine." (2014).

- "Ukraine clashes with Russia over 1930s famine". The Irish Times. Apr 29, 2008. Retrieved 2017-04-10.

- Marson, James (2009-11-18). "Ukraine's forgotten famine". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-04-10.

- Young, Cathy (2015-10-31). "Russia Denies Stalin's Killer Famine". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2017-04-10.

- "The Siege of Leningrad, 1941 – 1944". www.eyewitnesstohistory.com. 2006. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- "History of St. Petersburg during World War II". www.saint-petersburg.com. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- Ellman, Michael (2000). "The 1947 Soviet famine and the entitlement approach to famines" (PDF). Cambridge Journal of Economics. Oxford University Press. 24 (5): 603–630. doi:10.1093/cje/24.5.603. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- "Famine of 1946–1947". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. 2015-06-19. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- "Famine of 1946–7". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- Nove, Alec (1992). An Economic History of the USSR 1917–1991. Penguin Books. pp. 373–375.

- "Food security in the Russian Federation". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- "How Russia starves: the famine of 1992". 2016-09-06.

- Mungai, Christine (2015-11-03). "Drought in Russia and Ukraine threatens 30% of wheat crop—this could have unlikely political implications in Africa". MG Africa. Archived from the original on 2017-02-20. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- "Drought halts Russia grain exports". Express.co.uk. 2010-08-05. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

Notations

- Zima, V. F. (1999). Голод в СССР 1946–1947 годов: происхождение и последствия [The Famine of 1946–1947 in the USSR: Origins and Consequences] (in Russian). Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-3184-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dronin, Nikolai M.; Edward G. Bellinger (2005). Climate Dependence and Food Problems in Russia, 1900–1990: The Interaction of Climate and Agricultural Policy and Their Effect on Food Problems. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-7326-10-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ganson, Nicholas (2009). The Soviet Famine of 1946–47 in Global and Historical Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-61333-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Ellman, Michael (2007). "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. Routledge. 59 (4): 663–693. doi:10.1080/09668130701291899.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Art and photographs from the Great Famine

- The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931–1933