Drake Passage

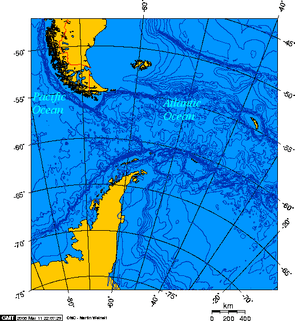

The Drake Passage (Spanish: Pasaje de Drake, Spanish: Mar de Drake, Spanish: Mar de Hoces) is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atlantic Ocean (Scotia Sea) with the southeastern part of the Pacific Ocean and extends into the Southern Ocean.

History

The passage received its name from the 16th-century English privateer Sir Francis Drake during his circumnavigation. Drake's only remaining ship, after having passed through the Strait of Magellan, was blown far south in September 1578. This incident demonstrated there was open water south of South America.[1]

Half a century earlier, after a gale had pushed them south from the entrance of the Strait of Magellan, the crew of the Spanish navigator Francisco de Hoces thought they saw a land's end and possibly inferred this passage in 1525.[2] For this reason, some Spanish and Latin American historians and sources call it Mar de Hoces after Francisco de Hoces.

The first recorded voyage through the passage was that of Eendracht, captained by the Dutch navigator Willem Schouten in 1616, naming Cape Horn in the process.

The first human-powered transit (by rowing) across the passage was accomplished on December 25, 2019, by captain Fiann Paul (Iceland), first mate Colin O'Brady (US), Andrew Towne (US), Cameron Bellamy (South Africa), Jamie Douglas-Hamilton (UK) and John Petersen (US).[3]

Geography

The 800-kilometre (500 mi) wide passage between Cape Horn and Livingston Island is the shortest crossing from Antarctica to another landmass. The boundary between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans is sometimes taken to be a line drawn from Cape Horn to Snow Island (130 kilometres (81 mi) north of mainland Antarctica), though the International Hydrographic Organization defines it as the meridian that passes through Cape Horn—67° 16′ W.[4] Both lines lie within the Drake Passage.

The other two passages around the extreme southern part of South America (though not going around Cape Horn as such), the Strait of Magellan and Beagle Channel, are narrow, leaving little maneuvering room for a ship. They can become icebound. Sometimes the wind blows so strongly that no sailing vessel can make headway against it. Most sailing ships thus prefer the Drake Passage, which is open water for hundreds of miles. The small Diego Ramírez Islands lie about 100 kilometres (62 mi) south-southwest of Cape Horn.

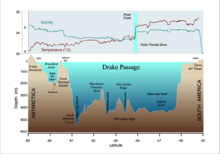

No significant land sits at the latitudes of the Drake Passage. That is important to the unimpeded flow of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, which carries a huge volume of water through the passage and around Antarctica.

The passage hosts whales, dolphins and seabirds including giant petrels, other petrels, albatrosses and penguins.

Fauna

Wildlife include the sooty shearwater, white-chinned petrel, southern giant-petrel, northern giant-petrel, black-browed albatross, Campbell albatross, grey-headed albatross, Atlantic yellow-nosed albatross, Indian yellow-nosed albatross, Buller's albatross, Salvin's albatross, shy albatross, southern royal albatross, northern royal albatross, wandering albatross, light-mantled albatross, sooty albatross, great shearwater, great-winged petrel, Kerguelen petrel, southern fulmar, Cape petrel, soft-plumaged petrel, white-headed petrel, atlantic petrel, grey petrel, antarctic prion, slender-billed prion, blue petrel, black-bellied storm-petrel, Wilson's storm-petrel, fin whale, sei whale, blue whale, humpback whale, southern right whale, sperm whale, hourglass dolphin, southern right whale dolphin, long-finned pilot whale, Arnoux's beaked whale, southern bottlenose whale, Cuvier's beaked whale, strap-toothed whale, Gray's beaked whale, and Hector's beaked whale.[5]

Gallery

- Rough seas are common in the Drake Passage

- Tourists watch whales in the Drake Passage

- Seabird (light-mantled sooty albatross) flying over the Drake Passage

- Humpback whales are a common sight in the Drake Passage

Hourglass dolphins leaping in the Passage

Hourglass dolphins leaping in the Passage Drake Passage or Mar de Hoces between South America and Antarctica

Drake Passage or Mar de Hoces between South America and Antarctica Drake Passage

Drake Passage

References

- Martinic B., Mateo (2019). "Entre el mito y la realidad. La situación de la misteriosa Isla Elizabeth de Francis Drake" [Between myth and reality. The situation of the mysterious Elizabeth Island of Francis Drake]. Magallania (in Spanish). 47 (1): 5–14. doi:10.4067/S0718-22442019000100005.

- Oyarzun, Javier, Expediciones españolas al Estrecho de Magallanes y Tierra de Fuego, 1976, Madrid: Ediciones Cultura Hispánica ISBN 84-7232-130-4

- "Impossible Row team achieve first ever row across the Drake Passage". Guinness World Records. 2019-12-27. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- International Hydrographic Organization, Limits of Oceans and Seas, Special Publication No. 28, 3rd edition, 1953 , p.4

- Lowen, James (2011). Antarctic Wildlife: A Visitor's Guide. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 44–49, 112–158. ISBN 9780691150338.

External links

![]()