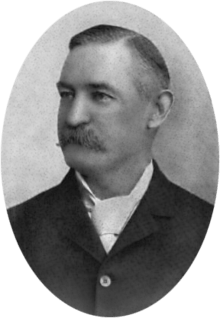

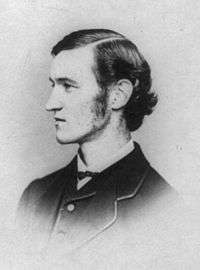

Dorence Atwater

Dorence Atwater (February 3, 1845 – November 26, 1910) was a Union Army soldier and later a businessman and diplomat who served as the United States Consul to Tahiti.

Dorence Atwater | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 3, 1845 |

| Died | November 26, 1910 (aged 65) San Francisco, California, US |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Union Army soldier, merchant, entrepreneur, diplomat |

| Spouse(s) | Princess Moetia Salmon |

In July 1863, during the American Civil War, Atwater was captured by the Confederate Army and found himself among the first batch of prisoners at the notorious Andersonville prisoner-of-war camp. He is notable for having created the Andersonville Death Register while imprisoned there, which recorded the identities of his fellow prisoners.[1] He made a secret copy of his list of the dead and missing which later allowed him, in cooperation with Clara Barton, to mark the graves of otherwise unknown soldiers.

Atwater was released from prison by President Andrew Johnson and sent to the Seychelles as a 23-year-old United States Consul. He was a proficient businessman who worked with lepers and other charities and was beloved by the Tahitian people, who called him "Tupuuataroa" (Wise Man).[2]

Early life

Dorence Atwater was born in Terryville, Connecticut, in 1845, the third child of Henry Atwater and Catherine Fenn Atwater. As a child, he worked as a store clerk due to his fine handwriting and aptitude for numbers.

Civil War

Atwater was only sixteen years old when the American Civil War broke out. After listening to a Union recruiter of German nationality, Atwater, too young to serve, lied about his age and joined anyway. Although Henry Atwater hauled his disobedient son to Hartford to confess his lie, Atwater badly wanted to go to war. For over two years, he served as a scout, delivered important messages, and was involved in many battles. He wrote to his father telling him how his outfit had destroyed a bridge: “Imagine,” he said, “hundreds of men, each with his canteen full of turpentine. He pours out the turpentine as he gallops across the bridge, and last man across throws the lit match.”

Prisoner-of-war

One morning in July 1863, Atwater was exercising his horse in the woods when he was captured by two Confederates disguised in Yankee uniforms. The Battle of Gettysburg had just occurred, and a new prison named Camp Sumter in southwest Georgia, known to the prisoners as Andersonville and to Atwater as "hell itself", had just opened. Andersonville had a quota of 400 prisoners a day. The Confederates picked up Atwater on their way through Richmond, Virginia, and he was among the first prisoners to be marched to Andersonville.

Atwater was ill when he arrived and was put into the prison hospital. Upon his recovery, his handwriting was discovered again and he was given the task of keeping the "Death List", a register of those who had died at the camp. He was ordered to produce two copies, one for the Confederates and one which, he was told, would go to the United States federal government. He suspected the Union would never see this copy and decided to keep his own list, hidden among the papers of the ones belonging to the Confederates. All the while, Atwater knew that if the prison leader, Captain Henry Wirz, discovered what he was doing, he would be hanged.[1][2]

When Atwater was released from Andersonville, the death list was completed. He dropped the huge list into his cotton laundry bag and walked through the Confederate lines with it.

Returning home

Shortly after Atwater arrived home, he pulled the Andersonville death list out of his bag and showed it to his father and siblings. There had been rumors that he had folded it and slipped it in the inner pocket of his coat. But as his brother Richard wrote, “First, the Union coats had no inside pockets, second, Dorence had no coat, and third, the huge, thick list was not folded.” Two days later, Atwater came down with diphtheria, typhoid, and scurvy. People rarely survived even one of these diseases, but Atwater did. Three weeks later, he was thin and weak but on the mend. He had just received a telegram requesting him to come to Washington, D.C. and bring the list. On the train there, word reached him that President Abraham Lincoln had been shot and was dying. Washington, D.C. was in chaos, and Atwater was still quite weak. A telegram then came from home notifying him that his father, who had nursed him through his illnesses, had diphtheria and was also dying. Atwater returned home at the first opportunity. His father died that night.

After handling the funeral, Atwater returned to Washington to begin work as an intern. He was barely 20 years old. There he met Clara Barton, who had the means to mark the Andersonville graves but no names with which to mark them; Atwater told her what she needed to know. This meeting began a lifelong friendship between Atwater and Barton.

General service and court-martial

Atwater took the death list and traveled with Barton, Dr. James Moore, and 42 headboard carvers to mark the graves of the soldiers who had died at Andersonville. Upon his return to Washington, D.C., he refused to reveal where his list was and was taken to be court-martialed. Barton consulted with President Andrew Johnson and Atwater received a general pardon. He later trained to be the U.S. Consul to the Seychelles Islands. The death list was eventually published by the federal government and reprinted by the New York Times.

U.S. Consul to Tahiti

After three years, Atwater was sent to be Consul to Tahiti. There he fell in love with Princess Moetia Salmon, or "Moe", the sister of Queen Marau and the second consort of King Pōmare V of Tahiti. Moetia had been educated in France and England. They were married in 1875.

The Atwaters had a home in San Francisco as well as in Tahiti. Their San Francisco house stood on Market Street, and while they were vacationing in Mexico, the great earthquake of 1906 occurred. In order to create a firebreak, Market Street had to be demolished by explosives and with it, the Atwater home. In their house was the original death list, the one Atwater had copied at the risk of his life.

Death and legacy

Atwater died on November 26, 1910, in San Francisco, at the age of 65.

He was interred in San Francisco while the royals of Tahiti planned to have his body returned. Atwater was the first non-royal to be given a royal funeral in Tahiti. He was buried beneath a 7000 lb stone. On one side is carved “Tupuuataroa” (Wise Man). On the other side, the inscription reads, “He builded better than he knew that one day he might awake in surprise to found he had wrought a monument more enduring than brass.” Princess Moe died in 1935, at the age of 87, and is buried next to Atwater.[1]

See also

References

Further reading

- Safranski, Debby Burnett. "Angel of Andersonville, Prince of Tahiti: The Extraordinary Life of Dorence Atwater". Alling-Porterfield Publishing House. 2008. ISBN 978-0-9749767-1-6