Distyly

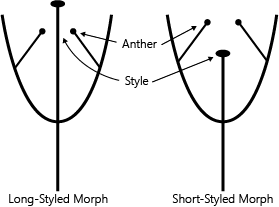

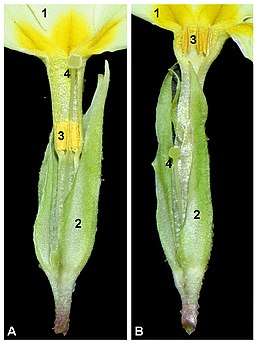

Distyly is a type of heterostyly in which a plant demonstrates reciprocal herkogamy. This breeding system is characterized by two separate flower morphs, where individual plants produce flowers that either have long styles and short stamens (referred to as “pin” or “long-styled” flowers), or that have short styles and long stamens (referred to as “thrum” or “short-styled” flowers).[1] However, distyly can refer to any plant that has two morphs if at least one of the following characteristics between flowers produced by different plants is true; there is a difference in style length, filament length, pollen size or shape, or the surface of the stigma.[2] Most distylous plants are self-incompatible so they cannot fertilize ovules in their own flowers. Specifically these plants exhibit intra-morph self-incompatibility, flowers of the same style morph are incompatible.[3]

Background

In a study of Primula veris it was found that pin flowers exhibit higher rates of self-pollination and capture more pollen than the thrum morph.[4] Different pollinators show varying levels of success while pollinating the different Primula morphs, the head or proboscis length of a pollinator is positively correlated to the uptake of pollen from long styled flowers and negatively correlated for pollen uptake on short styled flowers.[5] The opposite is true for pollinators with smaller heads, such as bees, they uptake more pollen from short styled morphs than long styled ones.[5] The differentiation in pollinators allows the plants to reduce levels of intra-morph pollination.

Charles Darwin made the first scientific account of distyly in 1877 in his book The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species.[6]

Evolution of dystyly

There are three main hypotheses for the evolution of dystyly, the loss of alleles hypothesis, the tristyly route hypothesis and evolution through herkogamy.

- The loss of alleles hypothesis postulates that heteromorphic self-incompatibility is a degenerate form of homomorphic self-incompatibility. One of the main arguments are that most dystylous plants are in families where most other species are homomorphic self-incompatible.[7] Muenchow (1982) ran simulations of a population with four alleles at the incompatibility loci and found that if one of the two loci is tightly linked to the self-incompatibility locus then the non-linked locus will be driven to extinction. The tightly linked loci is made up of two alleles, one dominant and one recessive giving rise to the two distylous morphs.[8]

- The Tristyly route hypothesis if championed by Robert Ornduff (1964) and suggests that distyly formed after secondary loss of a mid-style morph in trystylous plants. He supported this model by showing lower fitness of the mid-styled morph compared to the long and short style morphs in Oxalis suksdorfii [9]

- Evolution through herkogamy hypothesis was made popular by David Lloyd and C.J Webb and is an extension of the hypothesis put forward by Charles Darwin in 1862.[6] In this model, distylous plants first evolved from a monomorphic ancestor and then developed reciprocal herkogamy to increase inter-morph pollination success.[10]

Genetic control of distyly

The morph of a flower is commonly determined by a single locus with two alleles. Homozygous recessive (ss) results in a long-styled flower and heterozygous (Ss) or homozygous dominant (SS) result in a short-styled flower. If heteromorphic incompatibility is strong then the homozygous dominant individuals are rare.[11] Some species possessing distyly are tetraploids rather than diploids, yet less is known about these species.[11]

List of families with distylous species [4]

References

- Lewis, D. (1942). "The Physiology of Incompatibility in Plants. I. The Effect of Temperature". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 131 (862): 13–26. ISSN 0080-4649.

- Muenchow, Gayle (August 1982). "A loss-of-alleles model for the evolution of distyly". Heredity. 49 (1): 81–93. doi:10.1038/hdy.1982.67. ISSN 0018-067X.

- Barrett, Spencer C. H.; Cruzan, Mitchell B. (1994), "Incompatibility in heterostylous plants", Advances in Cellular and Molecular Biology of Plants, Springer Netherlands, pp. 189–219, ISBN 978-90-481-4340-5, retrieved 2020-05-08

- Ganders, Fred R. (December 1979). "The biology of heterostyly". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 17 (4): 607–635. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1979.10432574. ISSN 0028-825X.

- Deschepper, P; Brys, R; Jacquemyn, H (2018-03-01). "The impact of flower morphology and pollinator community composition on pollen transfer in the distylous Primula veris". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 186 (3): 414–424. doi:10.1093/botlinnean/box097. ISSN 0024-4074.

- Darwin, Charles (1877). The different forms of flowers on plants of the same species by Charles Darwin ... D. Appleton and Co. OCLC 894148387.

- Crowe, Leslie K (1964). "The evolution of outbreeding in plants". Heredity. 19 (3): 435–457. doi:10.1038/hdy.1964.53. ISSN 0018-067X – via nature.

- Muenchow, Gayle (1982). "A loss-of-alleles model for the evolution of distyly". Heredity. 49 (1): 81–93. doi:10.1038/hdy.1982.67. ISSN 0018-067X.

- Ornduff, Robert (1964). "The Breeding System Of Oxalis Suksdorfii". American Journal of Botany. 51 (3): 307–314. doi:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1964.tb06635.x – via Botanical Society of America.

- Barrett, Spencer C. H.; Lloyd, D.G.; Webb, C.J. (1992). "6". Evolution and Function of Heterostyly. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 151–178. ISBN 978-3-642-86656-2. OCLC 851381990.

- Shore, Joel S; Barrett, Spencer C H (October 1985). "The genetics of distyly and homostyly in Turners ulmifolia L. (Turneraceae)". Heredity. 55 (2): 167–174. doi:10.1038/hdy.1985.88. ISSN 0018-067X.