Digital art

Digital art is an artistic work or practice that uses digital technology as part of the creative or presentation process. Since the 1960s, various names have been used to describe the process, including computer art and multimedia art.[1] Digital art is itself placed under the larger umbrella term new media art.[2][3]

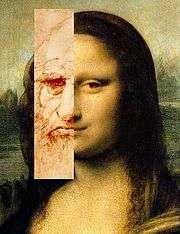

After some initial resistance,[4] the impact of digital technology has transformed activities such as painting, drawing, sculpture and music/sound art, while new forms, such as net art, digital installation art, and virtual reality, have become recognized artistic practices.[5] More generally the term digital artist is used to describe an artist who makes use of digital technologies in the production of art. In an expanded sense, "digital art" is contemporary art that uses the methods of mass production or digital media.[6]

The techniques of digital art are used extensively by the mainstream media in advertisements, and by film-makers to produce visual effects. Desktop publishing has had a huge impact on the publishing world, although that is more related to graphic design. Both digital and traditional artists use many sources of electronic information and programs to create their work.[7] Given the parallels between visual and musical arts, it is possible that general acceptance of the value of digital visual art will progress in much the same way as the increased acceptance of electronically produced music over the last three decades.[8]

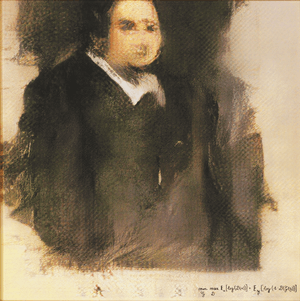

Digital art can be purely computer-generated (such as fractals and algorithmic art) or taken from other sources, such as a scanned photograph or an image drawn using vector graphics software using a mouse or graphics tablet.[9] Though technically the term may be applied to art done using other media or processes and merely scanned in, it is usually reserved for art that has been non-trivially modified by a computing process (such as a computer program, microcontroller or any electronic system capable of interpreting an input to create an output); digitized text data and raw audio and video recordings are not usually considered digital art in themselves, but can be part of the larger project of computer art and information art.[10] Artworks are considered digital painting when created in similar fashion to non-digital paintings but using software on a computer platform and digitally outputting the resulting image as painted on canvas.[11]

Andy Warhol created digital art using a Commodore Amiga where the computer was publicly introduced at the Lincoln Center, New York in July 1985. An image of Debbie Harry was captured in monochrome from a video camera and digitized into a graphics program called ProPaint. Warhol manipulated the image adding colour by using flood fills.[12][13]

At present—and whatever else can be said, pro or con, about the effects of digital technology on the arts—there seems to be a strong consensus within the digital art community that it has created a "vast expansion of the creative sphere", i.e., that it has greatly broadened the creative opportunities available to professional and non-professional artists alike.[14]

Computer-generated visual media

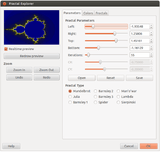

Digital visual art consists of either 2D visual information displayed on an electronic visual display or information mathematically translated into 3D information, viewed through perspective projection on an electronic visual display. The simplest is 2D computer graphics which reflect how you might draw using a pencil and a piece of paper. In this case, however, the image is on the computer screen and the instrument you draw with might be a tablet stylus or a mouse. What is generated on your screen might appear to be drawn with a pencil, pen or paintbrush. The second kind is 3D computer graphics, where the screen becomes a window into a virtual environment, where you arrange objects to be "photographed" by the computer. Typically a 2D computer graphics use raster graphics as their primary means of source data representations, whereas 3D computer graphics use vector graphics in the creation of immersive virtual reality installations. A possible third paradigm is to generate art in 2D or 3D entirely through the execution of algorithms coded into computer programs. This can be considered the native art form of the computer, and an introduction to the history of which available in an interview with computer art pioneer Frieder Nake.[15] Fractal art, Datamoshing, algorithmic art and real-time generative art are examples.

Computer generated 3D still imagery

3D graphics are created via the process of designing imagery from geometric shapes, polygons or NURBS curves[16] to create three-dimensional objects and scenes for use in various media such as film, television, print, rapid prototyping, games/simulations and special visual effects.

There are many software programs for doing this. The technology can enable collaboration, lending itself to sharing and augmenting by a creative effort similar to the open source movement, and the creative commons in which users can collaborate in a project to create art.

Pop surrealist artist Ray Caesar works in Maya (a 3D modeling software used for digital animation), using it to create his figures as well as the virtual realms in which they exist.

Computer generated animated imagery

Computer-generated animations are animations created with a computer, from digital models created by the 3D artists or procedurally generated. The term is usually applied to works created entirely with a computer. Movies make heavy use of computer-generated graphics; they are called computer-generated imagery (CGI) in the film industry. In the 1990s, and early 2000s CGI advanced enough so that for the first time it was possible to create realistic 3D computer animation, although films had been using extensive computer images since the mid-70s. A number of modern films have been noted for their heavy use of photo realistic CGI.[17]

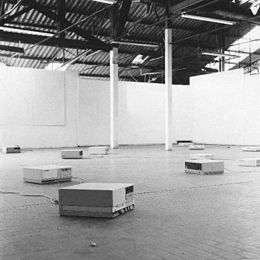

Digital installation art

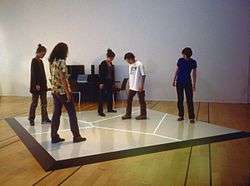

Digital installation art constitutes a broad field of activity and incorporates many forms. Some resemble video installations, particularly large scale works involving projections and live video capture. By using projection techniques that enhance an audience's impression of sensory envelopment, many digital installations attempt to create immersive environments. Others go even further and attempt to facilitate a complete immersion in virtual realms. This type of installation is generally site-specific, scalable, and without fixed dimensionality, meaning it can be reconfigured to accommodate different presentation spaces.[19]

Noah Wardrip-Fruin's "Screen" (2003) is an example of interactive digital installation art which makes use of a Cave Automatic Virtual Environment to create an interactive experience.[20] Scott Snibbe's "Boundary Functions" is an example of augmented reality digital installation art, which responds to people who enter the installation by drawing lines between people indicating their personal space.[18]

Art theorists and historians

Notable art theorists and historians in this field include Oliver Grau, Jon Ippolito, Christiane Paul, Frank Popper, Jasia Reichardt, Mario Costa, Christine Buci-Glucksmann, Dominique Moulon, Robert C. Morgan, Roy Ascott, Catherine Perret, Margot Lovejoy, Edmond Couchot, Fred Forest and Edward A. Shanken.

Subtypes

- Art game

- Computer art scene

- Computer music

- Cyberarts

- Digital illustration

- Digital imaging

- Digital painting

- Digital photography

- Digital poetry

- Digital architecture

- Dynamic Painting

- Electronic music

- Evolutionary art

- Fractal art

- Generative art

- Generative music

- GIF art

- Immersion (virtual reality)

- Interactive art

- Internet art

- Motion graphics

- Music visualization

- Photo manipulation

- Pixel art

- Render art

- Software art

- Systems art

- Textures

- Tradigital art

Related organizations and conferences

See also

References

- Reichardt, Jasia (1974). "Twenty years of symbiosis between art and science". Art and Science. XXIV, (1): 41–53.

- Christiane Paul (2006). Digital Art, pp. 7–8. Thames & Hudson.

- Lieser, Wolf. Digital Art. Langenscheidt: h.f. ullmann. 2009, pp. 13–15

- Taylor, G. D. (2012). The soulless usurper: Reception and criticism of early computer art. In H. Higgins, & D. Kahn (Eds.), Mainframe experimentalism: Early digital computing in the experimental arts. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

- Donald Kuspit The Matrix of Sensations VI: Digital Artists and the New Creative Renaissance

- Charlie Gere Art, Time and Technology: Histories of the Disappearing Body (Berg, 2005). ISBN 978-1-84520-135-7 This text concerns artistic and theoretical responses to the increasing speed of technological development and operation, especially in terms of so-called 'real-time' digital technologies. It draws on the ideas of Jacques Derrida, Bernard Stiegler, Jean-François Lyotard and André Leroi-Gourhan, and looks at the work of Samuel Morse, Vincent van Gogh and Malevich, among others.

- Frank Popper, Art of the Electronic Age, Thames & Hudson, 1997.

- Charlie Gere, (2002) Digital Culture, Reaktion.

- Christiane Paul (2006). Digital Art, pp. 27–67. Thames & Hudson.

- Wands, Bruce (2006). Art of the Digital Age, pp. 10–11. Thames & Hudson.

- Paul, Christiane (2006). Digital Art, pp. 54–60. Thames & Hudson.

- 'Reimer, Jeremy (October 21, 2007). "A history of the Amiga, part 4: Enter Commodore". Arstechnica.com. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- YouTube.

- Bessette, Juliette, Frederic Fol Leymarie, and Glenn W. Smith (16 September 2019). "Trends and Anti-Trends in Techno-Art Scholarship: The Legacy of the Arts "Machine" Special Issues". Arts. 8 (3): 120. doi:10.3390/arts8030120.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Smith, Glenn (31 May 2019). "An Interview with Frieder Nake". Arts. 8 (2): 69. doi:10.3390/arts8020069.

- Wands, Bruce (2006). Art of the Digital Age, pp. 15–16. Thames & Hudson.

- Lev Manovich (2001) The Language of New Media Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- "Boundary Functions"

- Paul, Christiane (2006). Digital Art, pp 71. Thames & Hudson.

- "screen - noah wardrip-fruin".

External links

| Library resources about Digital art |

- Dreher, Thomas. "History of Computer Art"

- Zorich, Diane M. "Transitioning to a Digital World"