Degrowth

Degrowth (French: décroissance) is a term used for both a political, economic, and social movement as well as a set of theories that critiques the paradigm of economic growth.[1] It is based on ideas from a diverse range of lines of thought such as political ecology, ecological economics, feminist political ecology, and environmental justice. Degrowth emphasizes the need to reduce global consumption and production (social metabolism) and advocates a socially just and ecologically sustainable society with well-being the indicator of prosperity in place of GDP. Degrowth highlights the importance of autonomy, care work, self-organization, commons, community, localism, work sharing, happiness and conviviality.[2][3][4][5][6]

Background

The movement arose from concerns over the perceived consequences of the productivism and consumerism associated with industrial societies (whether capitalist or socialist) including:[3]

- The reduced availability of energy sources (see peak oil)

- The declining quality of the environment (see global warming, pollution, threats to biodiversity)

- The decline in the health of flora and fauna upon which humans depend (see Holocene extinction)

- The rise of negative societal side-effects (see unsustainable development, poorer health, poverty)

- The ever-expanding use of resources by First World countries to satisfy lifestyles that consume more food and energy, and produce greater waste, at the expense of the Third World (see neocolonialism)

In academia, a study gathered degrowth proposals and defined the movement with three main goals[7]: (1) Reduce the environmental impact of human activity; (2) Redistribute income and wealth both within and between countries; (3) Promote the transition from a materialistic to a convivial and participatory society.

Resource depletion

As economies grow, the need for resources grows accordingly (unless there are changes in efficiency or demand for different products due to price changes). There is a fixed supply of non-renewable resources, such as petroleum (oil), and these resources will inevitably be depleted. Renewable resources can also be depleted if extracted at unsustainable rates over extended periods. For example, this has occurred with caviar production in the Caspian Sea.[8] There is much concern as to how growing demand for these resources will be met as supplies decrease. Many organizations and governments look to energy technologies such as biofuels, solar cells, and wind turbines to meet the demand gap after peak oil. Others have argued that none of the alternatives could effectively replace versatility and portability of oil.[9] Authors of the book Techno-Fix criticize technological optimists for overlooking the limitations of technology in solving agricultural and social challenges arising from growth.[10]

Proponents of degrowth argue that decreasing demand is the only way of permanently closing the demand gap. For renewable resources, demand, and therefore production, must also be brought down to levels that prevent depletion and are environmentally healthy. Moving toward a society that is not dependent on oil is seen as essential to avoiding societal collapse when non-renewable resources are depleted.[11]

Ecological footprint

The ecological footprint is a measure of human demand on the Earth's ecosystems. It compares human demand with planet Earth's ecological capacity to regenerate. It represents the amount of biologically productive land and sea area needed to regenerate the resources a human population consumes and to absorb and render harmless the corresponding waste. According to a 2005 Global Footprint Network report,[12] inhabitants of high-income countries live off of 6.4 global hectares (gHa), while those from low-income countries live off of a single gHa. For example, while each inhabitant of Bangladesh lives off of what they produce from 0.56 gHa, a North American requires 12.5 gHa. Each inhabitant of North America uses 22.3 times as much land as a Bangladeshi. According to the same report, the average number of global hectares per person was 2.1, while current consumption levels have reached 2.7 hectares per person. In order for the world's population to attain the living standards typical of European countries, the resources of between three and eight planet Earths would be required with current levels of efficiency and means of production. In order for world economic equality to be achieved with the current available resources, proponents say rich countries would have to reduce their standard of living through degrowth. The constraints on resources would eventually lead to a forced reduction in consumption. Controlled reduction of consumption would reduce the trauma of this change assuming no technological changes increase the planet's carrying capacity.

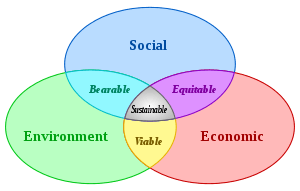

Degrowth and sustainable development[13]

Degrowth thought is in opposition to all forms of productivism (the belief that economic productivity and growth is the purpose of human organization). It is, thus, opposed to the current form of sustainable development.[14] While the concern for sustainability does not contradict degrowth, sustainable development is rooted in mainstream development ideas that aim to increase capitalist growth and consumption. Degrowth therefore sees sustainable development as an oxymoron,[15] as any development based on growth in a finite and environmentally stressed world is seen as inherently unsustainable. Critics of degrowth argue that a slowing of economic growth would result in increased unemployment, increased poverty, and decreased income per capita. Many who understand the devastating environmental consequences of growth still advocate for economic growth in the South, even if not in the North. But, a slowing of economic growth would fail to deliver the benefits of degrowth—self-sufficiency, material responsibility—and would indeed lead to decreased employment. Rather, degrowth proponents advocate the complete abandonment of the current (growth) economic model, suggesting that relocalizing and abandoning the global economy in the Global South would allow people of the South to become more self-sufficient and would end the overconsumption and exploitation of Southern resources by the North.[15]

"Rebound effect"

Technologies designed to reduce resource use and improve efficiency are often touted as sustainable or green solutions. Degrowth literature, however, warns about these technological advances due to the "rebound effect".[16] This concept is based on observations that when a less resource-exhaustive technology is introduced, behavior surrounding the use of that technology may change, and consumption of that technology could increase or even offset any potential resource savings.[17] In light of the rebound effect, proponents of degrowth hold that the only effective 'sustainable' solutions must involve a complete rejection of the growth paradigm and a move toward a degrowth paradigm. There are also fundamental limits to technological solutions in the pursuit of degrowth, as all engagements with technology increase the cumulative matter-energy throughput.[18] However, the convergence of digital commons of knowledge and design with distributed manufacturing technologies may arguably hold potential for building degrowth future scenarios.[19]

Origins of the movement

The contemporary degrowth movement can trace its roots back to the anti-industrialist trends of the 19th century, developed in Great Britain by John Ruskin, William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement (1819–1900), in the United States by Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862), and in Russia by Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910).[20]

The concept of "degrowth" proper appeared during the 1970s, proposed by André Gorz (1972) and intellectuals such as Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, Jean Baudrillard, Edward Goldsmith, E.F. Schumacher, Erich Fromm, Paul Goodman and Ivan Illich, whose ideas reflect those of earlier thinkers, such as the economist E. J. Mishan,[21] the industrial historian Tom Rolt,[22] and the radical socialist Tony Turner. The writings of Mahatma Gandhi and J. C. Kumarappa also contain similar philosophies, particularly regarding his support of voluntary simplicity.

More generally, degrowth movements draw on the values of humanism, enlightenment, anthropology and human rights.[23]

Club of Rome reports

The world's leaders are correctly fixated on economic growth as the answer to virtually all problems, but they're pushing it with all their might in the wrong direction.

In 1968, the Club of Rome, a think tank headquartered in Winterthur, Switzerland, asked researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for a report on the limits of our world system and the constraints it puts on human numbers and activity. The report, called The Limits to Growth, published in 1972, became the first significant study to model the consequences of economic growth.

The reports (also known as the Meadows Reports) are not strictly the founding texts of the degrowth movement, as these reports only advise zero growth, and have also been used to support the sustainable development movement. Still, they are considered the first studies explicitly presenting economic growth as a key reason for the increase in global environmental problems such as pollution, shortage of raw materials, and the destruction of ecosystems. The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update was published in 2004,[25] and in 2012, a 40-year forecast from Jørgen Randers, one of the book's original authors, was published as 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years.[26]

Lasting influence of Georgescu-Roegen

The degrowth movement recognises Romanian American mathematician, statistician and economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen as the main intellectual figure inspiring the movement.[27][28]:548f [29]:1742 [30]:xi [2]:1f In his work, The Entropy Law and the Economic Process, Georgescu-Roegen argues that economic scarcity is rooted in physical reality; that all natural resources are irreversibly degraded when put to use in economic activity; that the carrying capacity of Earth—that is, Earth's capacity to sustain human populations and consumption levels—is bound to decrease sometime in the future as Earth's finite stock of mineral resources is presently being extracted and put to use; and consequently, that the world economy as a whole is heading towards an inevitable future collapse.[31]

Georgescu-Roegen's intellectual inspiration to degrowth dates back to the 1970s.[32] When Georgescu-Roegen delivered a lecture at the University of Geneva in 1974, he made a lasting impression on the young, newly graduated French historian and philosopher, Jacques Grinevald, who had earlier been introduced to Georgescu-Roegen's works by an academic advisor. Georgescu-Roegen and Grinevald became friends, and Grinevald devoted his research to a closer study of Georgescu-Roegen's work. As a result, in 1979, Grinevald published a French translation of a selection of Georgescu-Roegen's articles entitled Demain la décroissance: Entropie – Écologie – Économie ('Tomorrow, the Decline: Entropy – Ecology – Economy').[33] Georgescu-Roegen, who spoke French fluently, approved the use of the term décroissance in the title of the French translation. The book gained influence in French intellectual and academic circles from the outset. Later, the book was expanded and republished in 1995, and once again in 2006; however, the word Demain ('tomorrow') was removed from the title of the book in the second and third editions.[29]:1742[33][34]:15f

By the time Grinevald suggested the term décroissance to form part of the title of the French translation of Georgescu-Roegen's work, the term had already permeated French intellectual circles since the early-1970s to signify a deliberate political action to downscale the economy on a permanent and voluntary basis.[3]:195 Simultaneously, but independently, Georgescu-Roegen criticised the ideas of The Limits to Growth and Herman Daly's steady-state economy in his article, "Energy and Economic Myths", delivered as a series of lectures from 1972, but not published before 1975. In the article, Georgescu-Roegen stated the following:

[Authors who] were set exclusively on proving the impossibility of growth ... were easily deluded by a simple, now widespread, but false syllogism: Since exponential growth in a finite world leads to disasters of all kinds, ecological salvation lies in the stationary state. ... The crucial error consists in not seeing that not only growth, but also a zero-growth state, nay, even a declining state which does not converge toward annihilation, cannot exist forever in a finite environment.[35]:366f

... [T]he important, yet unnoticed point [is] that the necessary conclusion of the arguments in favor of that vision [of a stationary state] is that the most desirable state is not a stationary, but a declining one. Undoubtedly, the current growth must cease, nay, be reversed.[35]:368f [Emphasis in original]

When reading this particular passage of the text, Grinevald realised that no professional economist of any orientation had ever reasoned like this before. Grinevald also realised the congruence of Georgescu-Roegen's viewpoint and the French debates occurring at the time; this resemblance was captured in the title of the French edition. Taken together, the translation of Georgescu-Roegen's work into French both fed on and gave further impetus to the concept of décroissance in France—and everywhere else in the francophone world—thereby creating something of an intellectual feedback loop.[29]:1742 [34]:15f [3]:197f

By the 2000s, when décroissance was to be translated from French back into English as the catchy banner for the new social movement, the original term "decline" was deemed inappropriate and misdirected for the purpose: "Decline" usually refers to an unexpected, unwelcome, and temporary economic recession, something to be avoided or quickly overcome. Instead, the neologism "degrowth" was coined to signify a deliberate political action to downscale the economy on a permanent, conscious basis—as in the prevailing French usage of the term—something good to be welcomed and maintained, or so followers believe.[28]:548 [34]:15f [36]:874–876

When the first international degrowth conference was held in Paris in 2008, the participants honoured Georgescu-Roegen and his work.[37]:15f, 28, et passim In his manifesto on Petit traité de la décroissance sereine ("Farewell to Growth"), the leading French champion of the degrowth movement, Serge Latouche, credited Georgescu-Roegen as the "...main theoretical source of degrowth".[27] Likewise, Italian degrowth theorist Mauro Bonaiuti considered Georgescu-Roegen's work to be "one of the analytical cornerstones of the degrowth perspective".[30]

Serge Latouche

Serge Latouche, a professor of economics at the University of Paris-Sud, has noted that:

If you try to measure the reduction in the rate of growth by taking into account damages caused to the environment and its consequences on our natural and cultural patrimony, you will generally obtain a result of zero or even negative growth. In 1991, the United States spent 115 billion dollars, or 2.1% of the GDP on the protection of the environment. The Clean Air Act increased this cost by 45 or 55 million dollars per year. [...] The World Resources Institute tried to measure the rate of the growth taking into account the punishment exerted on the natural capital of the world, with an eye towards sustainable development. For Indonesia, it found that the rate of growth between 1971 and 1984 would be reduced from 7.1 to 4% annually, and that was by taking only three variables into consideration: deforestation, the reduction in the reserves of oil and natural gas, and soil erosion.[38][39]

Schumacher and Buddhist economics

E. F. Schumacher's 1973 book Small Is Beautiful predates a unified degrowth movement, but nonetheless serves as an important basis for degrowth ideas. In this book he critiques the neo-liberal model of economic development, arguing that an increasing "standard of living", based on consumption, is absurd as a goal of economic activity and development. Instead, under what he refers to as Buddhist economics, we should aim to maximize well-being while minimizing consumption.[40]

Ecological and social issues

In January 1972, Edward Goldsmith and Robert Prescott-Allen—editors of The Ecologist—published A Blueprint for Survival, which called for a radical programme of decentralisation and deindustrialization to prevent what the authors referred to as "the breakdown of society and the irreversible disruption of the life-support systems on this planet".

In 2019, a summary for policymakers of the largest, most comprehensive study to date of biodiversity and ecosystem services was published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. The report was finalised in Paris. The main conclusions:

1. Over the last 50 years, the state of nature has deteriorated at an unprecedented and accelerating rate.

2. The main drivers of this deterioration have been changes in land and sea use, exploitation of living beings, climate change, pollution and invasive species. These five drivers, in turn, are caused by societal behaviors, from consumption to governance.

3. Damage to ecosystems undermines 35 of 44 selected UN targets, including the UN General Assembly's Sustainable Development Goals for poverty, hunger, health, water, cities' climate, oceans and land. It can cause problems with food, water and humanity's air supply.

4. To fix the problem, humanity needs transformative change, including sustainable agriculture, reductions in consumption and waste, fishing quotas and collaborative water management. Page 8 of the report proposes "enabling visions of a good quality of life that do not entail ever-increasing material consumption" as one of the main measures. The report states that "Some pathways chosen to achieve the goals related to energy, economic growth, industry and infrastructure and sustainable consumption and production (Sustainable Development Goals 7, 8, 9 and 12), as well as targets related to poverty, food security and cities (Sustainable Development Goals 1, 2 and 11), could have substantial positive or negative impacts on nature and therefore on the achievement of other Sustainable Development Goals".[41][42]

In a paper published in June 2020, a group of scientists argue that "green growth" or "sustainable growth" is a myth. "...we have to get away from our obsession with economic growth—we really need to start managing our economies in a way that protects our climate and natural resources, even if this means less, no or even negative growth." They conclude that a change in economic paradigms is imperative to prevent environmental destruction.[43][44]

Degrowth movement

Conferences

The movement has included international conferences,[45] promoted by the network Research & Degrowth (R&D),[46] in Paris (2008),[47] Barcelona (2010),[48] Montreal (2012),[49] Venice (2012),[50] Leipzig (2014), Budapest (2016),[51] and Malmö (2018).[52]

Barcelona Conference (2010)

The First International Conference on Economic Degrowth for Ecological Sustainability and Social Equity in Paris (2008) was a discussion about the financial, social, cultural, demographic, and environmental crisis caused by the deficiencies of capitalism and an explanation of the main principles of degrowth.[53] The Second International Conference in Barcelona focused on specific ways to implement a degrowth society.

Concrete proposals have been developed for future political actions, including:

- Promotion of local currencies, elimination of fiat money and reforms of interest

- Transition to non-profit and small scale companies

- Increase of local commons and support of participative approaches in decision-making

- Reducing working hours and facilitation of volunteer work

- Reusing empty housing and cohousing

- Introduction of the basic income and an income ceiling built on a maximum-minimum ratio

- Limitation of the exploitation of natural resources and preservation of the biodiversity and culture by regulations, taxes and compensations

- Minimize the waste production with education and legal instruments

- Elimination of mega infrastructures, transition from a car-based system to a more local, biking, walking-based one.

- Suppression of advertising from the public space[54]

The Barcelona conference had little influence on the world economic and political order. Criticism of the proposals arrived at in Barcelona, mostly financial, have inhibited change.[55]

Degrowth around the world

Although not explicitly called degrowth, movements inspired by similar concepts and terminologies can be found around the world, including Buen Vivir[56] in Latin America, the Zapatistas in Mexico, the Kurdish Rojava or Eco-Swaraj[57] in India.

Relation to other social movements

The degrowth movement has a variety of relations to other social movements and alternative economic visions, which range from collaboration to partial overlap. The Konzeptwerk Neue Ökonomie (Laboratory for New Economic Ideas), which hosted the 2014 international Degrowth conference in Leipzig, has published a project entitled "Degrowth in movement(s)"[58] in 2017, which maps relationships with 32 other social movements and initiatives. The relation to the environmental justice movement is especially visible.[2]

Criticisms, challenges and dilemmas

Critiques of degrowth concern the negative connotation that the term "degrowth" imparts, the misapprehension that growth is seen as unambiguously bad, the challenges and feasibility of a degrowth transition, as well as the entanglement of desirable aspects of modernity with the growth paradigm.

Criticisms

Negative connotation

The use of the term “degrowth” is criticized for being detrimental to the degrowth movement because it could carry a negative connotation,[59] in opposition to the positively perceived “growth”.[60] “Growth” is associated with the “up” direction and positive experiences, while “down” generates the opposite associations.[61] Research in political psychology has shown that the initial negative association of a concept, such as of “degrowth” with the negatively perceived “down”, can bias how the subsequent information on that concept is integrated at the unconscious level.[62] At the conscious level, degrowth can be interpreted negatively as the contraction of the economy,[59][63] although this is not the goal of a degrowth transition, but rather one of its expected consequences.[64] In the current economic system, a contraction of the economy is associated with a recession and its ensuing austerity measures, job cuts, or lower salaries.[63] Noam Chomsky commented[65] on the use of the term "degrowth": "When you say 'degrowth' it frightens people. It's like saying you're going to have to be poorer tomorrow than you are today, and it doesn't mean that."

Since "degrowth" contains the term "growth", there is also a risk of the term having a backfire effect, which would reinforce the initial positive attitude toward growth.[59] "Degrowth" is also criticized for being a confusing term, since its aim is not to halt economic growth as the word implies. Instead, agrowth is proposed as an alternative term that emphasizes that growth ceases to be an important policy objective, but that it can still be achieved as a side-effect of environmental and social policies.[63][66]

Marxist critique

Traditional Marxists distinguish between two types of value creation: that which is useful to mankind, and that which only serves the purpose of accumulating capital.[2]:86-87 Traditional Marxists consider that it is the exploitative nature and control of the capitalist production relations that is the determinant and not the quantity. According to Jean Zin, while the justification for degrowth is valid, it is not a solution to the problem.[67] Other Marxist writers have adopted positions close to the de-growth perspective. For example, John Bellamy Foster[68] and Fred Magdoff,[69] in common with David Harvey, Immanuel Wallerstein, Paul Sweezy and others focus on endless capital accumulation as the basic principle and goal of capitalism. This is the source of economic growth and, in the view of these writers, results in an unsustainable growth imperative. Foster and Magdoff develop Marx's own concept of the metabolic rift, something he noted in the exhaustion of soils by capitalist systems of food production, though this is not unique to capitalist systems of food production as seen in the Aral Sea. Many degrowth theories and ideas are based on neomarxist theory.[2]

Systems theoretical critique

In stressing the negative rather than the positive side(s) of growth, the majority of degrowth proponents remains focused on (de-)growth, thus co-performing and further sustaining the actually criticized unsustainable growth obsession. One way out of this paradox might be in changing the reductionist vision of growth as ultimately an economic concept, which proponents of both growth and degrowth commonly imply, for a broader concept of growth that allows for the observation of growth in other function systems of society. A corresponding recoding of growth-obsessed or capitalist organizations has been proposed.[70]

Challenges

Political and social spheres

The growth imperative is deeply entrenched in market capitalist societies such that it is necessary for their stability.[71] Moreover, the institutions of modern societies, such as the nation state, welfare, the labor market, education, academia, law and finance, have co-evolved along growth to sustain it.[72] A degrowth transition thus requires not only a change of the economic system but of all the systems on which it relies. As most people in modern societies are dependent on those growth-oriented institutions, the challenge of a degrowth transition also lies in the individual resistance to move away from growth.[73]

Agriculture

A degrowth society would require a shift from industrial agriculture to less intensive and more sustainable agricultural practices such as permaculture or organic agriculture, but it is not clear if any of those alternatives could feed the current and projected global population.[74][75] In the case of organic agriculture, Germany, for example, would not be able to feed its population under ideal organic yields over all of its arable land without meaningful changes to patterns of consumption, such as reducing meat consumption and food waste.[76][74] Moreover, labour productivity of non-industrial agriculture is significantly lower due to the reduced use or absence of fossil fuels, which leaves much less labour for other sectors.[77] Potential solutions to this challenge include scaling up approaches such as community-supported agriculture (CSA).

Dilemmas

Given that modernity has emerged with high levels of energy and material throughput, there is an apparent compromise between desirable aspects of modernity[78] (e.g., social justice, gender equality, long life expectancy, low infant mortality) and unsustainable levels of energy and material use.[79] Another way of looking at this is through the lens of the Marxist tradition, which relates the superstructure (culture, ideology, institutions) and the base (material conditions of life, division of labor). A degrowth society, by its drastically different material conditions, could produce equally drastic changes of the cultural and ideological spheres of society.[79] The political economy of global capitalism has generated a lot of bads, such as socioeconomic inequality and ecological devastation, which have engendered a lot of goods through individualization and increased spatial and social mobility.[80] This has allowed social emancipation at the level of gender equality,[81] disability, sexuality and anti-racism that has no historical precedent. The capitalist system, however, is also built on the exploitation of female reproductive labor as well as that of the Global South. Sexism and racism embedded in its structure. Therefore, some theories (such as Eco-Feminism or political ecology) argue that there cannot be equality regarding gender and the hierarchy between the Global North and South within capitalism.[82] Nevertheless, co-evolving aspects of global capitalism, liberal modernity, and the market society, are closely tied and will be difficult to separate to maintain liberal and cosmopolitan values in a degrowth society.[80]

Healthcare

It has been pointed out that there is an apparent trade-off between the ability of modern healthcare systems to treat individual bodies to their last breath and the broader global ecological risk of such an energy and resource intensive care. If this trade-off exists, a degrowth society would have to choose between prioritizing the ecological integrity and the ensuing collective health or maximizing the healthcare provided to individuals.[83] However, many degrowth scholars argue that the current system produces both psychological and physical damage to people. They insist that societal prosperity should be measured by well-being, not GDP.[2]:142

See also

- Degrowth advocates (category)

- A Blueprint for Survival

- Anarcho-primitivism

- Anti-capitalism

- Anti-consumerism

- Collapsology

- Ecological economics

- Edward Goldsmith

- André Gorz

- Ezra J. Mishan

- François Partant

- Genuine progress indicator

- GROWL

- L-shaped recession

- Political ecology

- Postdevelopment theory

- Power Down: Options and Actions for a Post-Carbon World

- Paradox of thrift

- The Path to Degrowth in Overdeveloped Countries

- Post-consumerism

- Post-growth

- Productivism

- Prosperity Without Growth

- Simple living

- Slow movement

- Steady-state economy

- Tim Jackson (economist)

- Transition town

- Uneconomic growth

- Voluntary childlessness

- Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt

Notes

- Kallis, Giorgos; Kostakis, Vasilis; Lange, Steffen; et al. (2018-10-17). "Research On Degrowth". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 43 (1): 291–316. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-102017-025941. ISSN 1543-5938.

- D'Alisa, Giacomo; et al., eds. (2015). Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era (Book info page containing download samples). London: Routledge. ISBN 9781138000766.

- Demaria, Federico; et al. (2013). "What is Degrowth? From an Activist Slogan to a Social Movement" (PDF). Environmental Values. 22 (2): 191–215. doi:10.3197/096327113X13581561725194. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-27.

- Martínez-Alier, Joan (10 February 2012). "Environmental Justice and Economic Degrowth: An Alliance between Two Movements Joan". Capitalism Nature Socialism. 23 (1): 51-73. doi:10.1080/10455752.2011.648839. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Demaria, Federico; Kothari, Ashish; Salleh, Ariel; Escobar, Arturo; Acosta, Alberto (2019). Pluriverse. A Post-Development Dictionary. New Delhi: Tulika Books. ISBN 9788193732984.

- "What is degrowth?". degrowth.info. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Cosme, Inês; Santos, Rui; O’Neill, Daniel W. (2017-04-15). "Assessing the degrowth discourse: A review and analysis of academic degrowth policy proposals". Journal of Cleaner Production. 149: 321–334. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.02.016. ISSN 0959-6526.

- Bardi, U. (2008) 'Peak Caviar'. The Oil Drum: Europe. http://europe.theoildrum.com/node/4367

- McGreal, R. 2005. 'Bridging the Gap: Alternatives to Petroleum (Peak Oil Part II)'. Raising the Hammer. http://www.raisethehammer.org/index.asp?id=119

- Huesemann, Michael H., and Joyce A. Huesemann (2011). Technofix: Why Technology Won’t Save Us or the Environment, New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada, ISBN 0865717044, 464 pp.

- Resilience.org. (October 20, 2009). Peak Oil Reports. http://www.resilience.org/stories/2009-10-20/peak-oil-reports-oct-20

- "Data Sources". footprintnetwork.org. Archived from the original on 2009-10-01.

- (Latouche 2009), pp. 9-13

- Lorek, Sylvia; Fuchs, Doris (2013). "Strong sustainable consumption governance – precondition for a degrowth path?" (PDF). Journal of Cleaner Production. 38: 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.08.008.

- Latouche, S. (2004). Degrowth Economics: Why less should be so much more. Le Monde Diplomatique.

- (Zehner 2012), pp.172–73, 333–34

- Binswanger, M. (2001). "Technological Progress and Sustainable Development: What About the Rebound Effect?". Ecological Economics. 36 (1): 119–32. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00214-7.

- Heikkurinen, Pasi (2018). "Degrowth by means of technology? A treatise for an ethos of releasement" (PDF). Journal of Cleaner Production. 197: 1654–1665. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.070.

- Kostakis, Vasilis; Latoufis, Kostas; Liarokapis, Minas; Bauwens, Michel (2018). "The convergence of digital commons with local manufacturing from a degrowth perspective: Two illustrative cases" (PDF). Journal of Cleaner Production. 197: 1684–1693. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.077.

- "Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era (Paperback) - Routledge". Routledge.com. p. 134. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- Mishan, Ezra J., The Costs of Economic Growth, Staples Press, 1967

- Rolt, L. T. C. (1947). High Horse Riderless. George Allen & Unwin. p. 171.

- d'Alisa, Giacomo; Demaria, Federico; Cattaneo, Claudio (2013). "Civil and Uncivil Actors for a Degrowth Society" (PDF). Journal of Civil Society. 9 (2): 212–224. doi:10.1080/17448689.2013.788935.

- Donella Meadows, edited by Diana Wright, Thinking in Systems: A Primer, Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008, page 146 (ISBN 9781603580557).

- Meadows, Donella H.; Randers, Jorgen; Meadows, Dennis L. (2004). The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update. White River Junction VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Co. ISBN 1931498512. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Randers, Jørgen (2012). 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years. White River Junction VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Co. ISBN 978-1-60358-467-8. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- (Latouche 2009), pp. 13-16

- Kerschner, Christian (2010). "Economic de-growth vs. steady-state economy" (PDF). Journal of Cleaner Production. 18 (6): 544–551. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.10.019.

- Martínez-Alier, Juan; et al. (2010). "Sustainable de-growth: Mapping the context, criticisms and future prospects of an emergent paradigm" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 69 (9): 1741–1747. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.04.017.

- Bonaiuti, Mauro, ed. (2011). From Bioeconomics to Degrowth: Georgescu-Roegen's "New Economics" in eight essays (Book info page at publisher's site). London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415587006.

- Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas (1971). The Entropy Law and the Economic Process (Full book accessible at Scribd). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674257801.

- Levallois, Clément (2010). "Can de-growth be considered a policy option? A historical note on Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen and the Club of Rome". Ecological Economics. 69 (11): 2271–2278. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.06.020. hdl:1765/20130. ISSN 0921-8009.

- Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas (1995) [1979]. Grinevald, Jacques; Rens, Ivo (eds.). La Décroissance: Entropie – Écologie – Économie (PDF contains full book) (2nd ed.). Paris: Sang de la terre.

- Grinevald, Jacques (2008). "Introduction to Georgescu-Roegen and Degrowth" (PDF contains all conference proceedings). In Flipo, Fabrice; Schneider, François (eds.). Proceedings of the First International Conference on Economic De-Growth for Ecological Sustainability and Social Equity. Paris. pp. 14–17.

- Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas (1975). "Energy and Economic Myths" (PDF). Southern Economic Journal. 41 (3): 347–381. doi:10.2307/1056148. JSTOR 1056148.

- Kallis, Giorgos (2011). "In defense of degrowth" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 70 (5): 873–880. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.12.007.; Kallis, Giorgos (February 2015). "The Degrowth Alternative". Great Transition Initiative.

- Flipo, Fabrice; Schneider, François, eds. (2008). Proceedings of the First International Conference on Economic De-Growth for Ecological Sustainability and Social Equity (PDF contains all conference proceedings). Paris.

- Hervé Kempf, L'économie à l'épreuve de l'écologie Hatier

- Latouche, Serge (2003) Decrecimiento y post-desarrollo El viejo topo, p.62

- Schumacher, E. F. (1973). Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered. New York: Perennial Library.

- Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (PDF). the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. 6 May 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- Deutsche Welle, Deutsche (May 6, 2019). "Why Biodiversity Loss Hurts Humans as Much as Climate Change Does". Ecowatch. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Overconsumption and growth economy key drivers of environmental crises" (Press release). Phys.org. University of New South Wales. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Wiedmann, T.; Lenzen, M.; Keyßer, L.T.; et al. (2020). "Scientists' warning on affluence". Nature Communications. 11 (3107). doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16941-y. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- (in French) "La genèse du Réseau Objection de Croissance en Suisse", Julien Cart, in Moins!, journal romand d'écologie politique, 12, July-August 2014.

- "Research & Degrowth". Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- "Décroissance économique pour la soutenabilité écologique et l'équité sociale". Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- "Degrowth Conference Barcelona 2010". Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- "International Conference on Degrowth in the Americas". Archived from the original on 2014-05-31. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- "International Degrowth Conference Venezia 2012". Retrieved 5 Dec 2012.

- "5th International Degrowth Conference in Budapest". 2015-03-26. Retrieved 2018-01-31.

- "Dialogues in turbulent times". Dialogues in turbulent times. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- Declaration of the Paris 2008 Conference. Retrieved from: http://degrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Declaration-Degrowth-Paris-2008.pdf

- 2nd Conference on Economic Degrowth for Ecological Sustainability and Social Ethic. 2010. Degrowth Declaration Barcelona 2010 and Working Groups Results. Retrieved from: http://barcelona.degrowth.org/ Archived 2014-04-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Responsabilité, Innovation & Management. 2011. Décroissance économique pour l'écologie, l'équité et le bien-vivre par François SCHNEIDER. Retrieved from http://www.openrim.org/Decroissance-economique-pour-l.html Archived 2014-02-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Balch, Oliver (2013-02-04). "Buen vivir: the social philosophy inspiring movements in South America". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-09-03.

- Kothari, Ashish; Demaria, Federico; Acosta, Alberto (2014). "Buen Vivir, Degrowth and Ecological Swaraj: Alternatives to sustainable development and the Green Economy". Development. 57 (3–4): 362–375. doi:10.1057/dev.2015.24.

- "Degrowth in movement(s)". Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- Drews, Stefan; Antal, Miklós (2016). "Degrowth: A 'missile word' that backfires?". Ecological Economics. 126: 182–187. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.04.001.

- Warriner, Amy Beth; Kuperman, Victor; Brysbaert, Marc (2013). "Norms of valence, arousal, and dominance for 13,915 English lemmas". Behavior Research Methods. 45 (4): 1191–1207. doi:10.3758/s13428-012-0314-x. PMID 23404613.

- Meier, B. P.; Robinson, M. D. (2004-04-01). "Why the Sunny Side Is Up: Associations Between Affect and Vertical Position". Psychological Science. 15 (4): 243–247. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00659.x. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 15043641.

- Lodge, Milton; Taber, Charles S. (2013). The Rationalizing Voter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139032490. ISBN 9781139032490.

- Van Den Bergh, Jeroen C.J.M. (2011). "Environment versus growth — A criticism of "degrowth" and a plea for "a-growth"". Ecological Economics. 70 (5): 881–890. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.09.035.

- Kallis, Giorgos; Kostakis, Vasilis; Lange, Steffen; Muraca, Barbara; Paulson, Susan; Schmelzer, Matthias (2018-10-17). "Research On Degrowth". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 43 (1): 291–316. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-102017-025941. ISSN 1543-5938.

- Levy, Andrea; Gonick, Cy; Lukacs, Martin (January 22, 2014). "The greening of Noam Chomsky: a conversation". Canadian Dimension. Open Publishing. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- van den Bergh, Jeroen C. J. M. (2017). "A third option for climate policy within potential limits to growth". Nature Climate Change. 7 (2): 107–112. Bibcode:2017NatCC...7..107V. doi:10.1038/nclimate3113. ISSN 1758-678X.

- L'écologie politique à l'ère de l'information, Ere, 2006, p. 68-69

- https://monthlyreview.org/press/books/pb2181/, Monthly Review Press.

- "Harmony and Ecological Civilization: Beyond the Capitalist Alienation of Nature". Monthly Review. June 2012.

- Roth, Steffen. "Growth and function. A viral research program for next organizations" (PDF). International Journal of Technology Management.

- Rosa, Hartmut; Dörre, Klaus; Lessenich, Stephan (2017). "Appropriation, Activation and Acceleration: The Escalatory Logics of Capitalist Modernity and the Crises of Dynamic Stabilization" (PDF). Theory, Culture & Society. 34 (1): 53–73. doi:10.1177/0263276416657600. ISSN 0263-2764.

- Luhmann, Niklas (1976). "The Future Cannot Begin: Temporal Structures in Modern Society". Social Research. 43: 130–152.

- Büchs, Milena; Koch, Max (2019). "Challenges for the degrowth transition: The debate about wellbeing". Futures. 105: 155–165. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2018.09.002.

- Gomiero, Tiziano (2018). "Agriculture and degrowth: State of the art and assessment of organic and biotech-based agriculture from a degrowth perspective". Journal of Cleaner Production. 197: 1823–1839. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.237.

- Ferguson, Rafter Sass; Lovell, Sarah Taylor (2014). "Permaculture for agroecology: design, movement, practice, and worldview. A review" (PDF). Agronomy for Sustainable Development. 34 (2): 251–274. doi:10.1007/s13593-013-0181-6. ISSN 1774-0746.

- Müller, Adrian. "Strategies for feeding the world more sustainably with organic agriculture" (PDF). nature.com. Springer Nature. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Giampietro, Mario (2011-10-12). The Metabolic Pattern of Societies. doi:10.4324/9780203635926. ISBN 9780203635926.

- Pinker, Steven (2019-01-03). Enlightenment Now. ISBN 9780141979090. OCLC 1083713125.

- Quilley, Stephen (2013). "De-Growth is Not a Liberal Agenda: Relocalisation and the Limits to Low Energy Cosmopolitanism". Environmental Values. 22 (2): 261–285. doi:10.3197/096327113X13581561725310.

- Kish, Kaitlin; Quilley, Stephen (2017). "Wicked Dilemmas of Scale and Complexity in the Politics of Degrowth". Ecological Economics. 142: 306–317. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.08.008.

- Felski, Rita (2009). Gender of Modernity. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674036796. OCLC 1041150387.

- Doyal, Len; Gough, Ian (1991). Towards a political economy of degrowth. London, New York: Rowman & Littlefield International, Ltd. p. 77. ISBN 9781786608963.

- Zywert, Katharine; Quilley, Stephen (2018). "Health systems in an era of biophysical limits: The wicked dilemmas of modernity". Social Theory & Health. 16 (2): 188–207. doi:10.1057/s41285-017-0051-4.

- Latouche, Serge (2009) [2007]. Farewell to Growth (PDF contains full book). Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-4616-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zehner, Ozzie (2012). Green Illusions. Lincoln & London: U. Neb. Press. ISBN 978-0803237759.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- First International De-growth Conference in Paris 18-19 April 2008

- 2nd Conference on Economic Degrowth for Ecological Sustainability and Social Equity. Barcelona 26-29 March 2010

- International Conference on Degrowth in the Americas, Montreal, 13-19 May 2012

- 3rd International Conference on degrowth for ecological sustainability and social equity (Venice, 19-23 September 2012)

- Peter Ainsworth on degrowth and sustainable development Published on La Clé des langues

- Club for Degrowth

- CBC Ideas podcast "The Degrowth Paradigm"; 54 minutes (Toronto 10 December 2013)