De mortuis nil nisi bonum

The Latin phrase De mortuis nihil nisi bonum (also De mortuis nil nisi bene [dicendum]) "Of the dead, [say] nothing but good", abbreviated as Nil nisi bonum, is a mortuary aphorism, indicating that it is socially inappropriate to speak ill of the dead.

The full sentence De mortuis nil nisi bonum dicendum est translates to "Of the dead nothing but good is to be said". Freer translations into English are often used as aphorisms, these include: "Speak no ill of the dead", "Of the dead, speak no evil", and "Do not speak ill of the dead".

The aphorism is first recorded in Greek, as τὸν τεθνηκóτα μὴ κακολογεῖν (tòn tethnekóta mè kakologeîn, "Do not speak ill of the dead"), attributed to Chilon of Sparta (ca. 600 BC), one of the Seven Sages of Greece, in the Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers (Book 1, Chapter 70) by Diogenes Laërtius, published in the early 4th century AD. The Latin version dates to the Italian Renaissance, from the translation of Diogenes' Greek by humanist monk Ambrogio Traversari (Laertii Diogenis vitae et sententiae eorum qui in philosophia probati fuerunt, published 1433).[1]

Usages

Literary

Novels

- The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867), by Anthony Trollope

After the sudden death of the Bishop's wife, the Archdeacon describes De mortuis as a proverb "founded in humbug" that only need be followed in public and is unable to bring himself to adopt "the namby-pamby every-day decency of speaking well of one of whom he had ever thought ill."

- The Power-House (1916), by John Buchan

After destroying the villain, Andrew Lumley, the hero, Sir Edward Leithen, speaks De mortuis & c., an abbreviated version of the phrase, about the dead Lumley.

- Deus Irae (1976), by Philip K. Dick and Roger Zelazny

Father Handy thinks of the phrase in reference to millions of people killed by nerve gas. He then subverts the phrase to "de mortuis nil nisi malum" in blaming them for complacently voting in the politicians responsible.

Short story

- “De Mortuis” (1942), by John Collier.

After an unwitting cuckold is accidentally informed of his wife’s infidelities, he plans an opportunistic revenge; the titular phrase, de mortuis, implies the murderous ending of the story.

- "EPICAC", by Kurt Vonnegut

After the demise of his friend/project - EPICAC, the supercomputer, the protagonist states the phrase in a memoir of someone who has done great for him.

Poetic

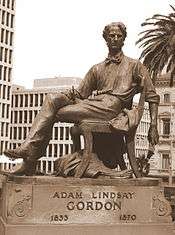

- In “Sunlight on the Sea” (The Philosophy of a Feast), by Adam Lindsay Gordon, the mortuary phrase is the penultimate line of the eighth, and final, stanza of the poem.

Philosophic

.jpg)

Cinematic

- In the war–adventure film Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

The phrase is cautiously used at the funeral of T. E. Lawrence, officiated at St Paul's Cathedral; two men, a clergyman and a soldier, Colonel Brighton, are observing a bust of the dead “Lawrence of Arabia”, and commune in silent mourning.

The clergyman asks: “Well, nil nisi bonum. But did he really deserve . . . a place in here?”

Colonel Brighton’s reply is a pregnant silence.

Theatrical

- In The Seagull (1896), by Anton Chekhov, a character mangles the mortuary phrase.

In Act 1, in an effort at light metaphor, the bourgeois character Ilya Afanasyevich Shamrayev, misquotes the Latin phrase Nil nisi bonum and conflates it with the maxim De gustibus non est disputandum (“About taste there is no disputing”), which results in the mixed mortuary opinion: De gustibus aut bene, aut nihil (“Let nothing be said of taste, but what is good”).[2]

- In Julius Caesar (1599) by William Shakespeare, Mark Antony uses what is possibly a perverted form of the phrase De mortuis nil nisi bonum, when he says:

The evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interred with their bones...[3]

Notes

- Traversari, Ambrogio (1432). Benedictus Brognolus (ed.). Laertii Diogenis vitae et sententiae eorvm qvi in philosophia probati fvervnt (in Latin). Venice: Impressum Venetiis per Nicolaum Ienson gallicum. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- Chekhov, Anton; Stephen Mulrine, Translator (1997). The Seagull. London: Nick Hern Books Ltd. pp. Introduction, p. xvii. ISBN 978-1-85459-193-7.

- Shakespeare, William. Julius Caesar.