David Biespiel

David Biespiel is an American poet, memoirist, and critic born in 1964 and raised in the Meyerland section of Houston, Texas. He is the founder of the Attic Institute of Arts and Letters in Portland, Oregon and Poet-in-Residence at Oregon State University.

David Biespiel | |

|---|---|

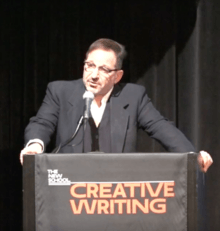

Biespiel speaking at the New School in New York, March 2016 | |

| Born | 18 February 1964. Tulsa, Oklahoma |

| Occupation | writer and professor |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Stanford University (1995), University of Maryland (1991), Boston University (1986) |

| Genre | poetry, memoir, criticism |

| Notable works | Republic Café (2019), The Education of a Young Poet (2017), A Long High Whistle (2015), Charming Gardeners (2013), The Book of Men and Women (2009), Wild Civility (2003) |

| Children | Lucas Biespiel |

| Website | |

| db1547 | |

Publications

Books

- A Place of Exodus, 2020

- Republic Cafe, 2019

- The Education of a Young Poet, 2017

- A Long High Whistle, 2015

- Charming Gardeners, 2013

- Every Writer Has a Thousand Faces, 2010

- The Book of Men and Women, 2009

- Wild Civility, 2003

- Pilgrims & Beggars, 2002

- Shattering Air, 1996

Edited Collections

- Poems of the American South (Random House: Everyman's Library Pocket Poets), 2014

- Long Journey: Contemporary Northwest Poets (Awarded the Pacific Northwest Bookseller's Award), 2006

Recording

Citizen Dave: Selected Poems 1996–2010

Awards

- National Book Critics Circle Balakian Award, finalist, 2019/2018

- Oregon Book Award in Nonfiction, A Long High Whistle, 2016

- Oregon Book Award in Poetry, The Book of Men and Women, 2011

- Lannan Fellowship, 2007

- Pacific Northwest Bookseller's Award, A Long Journey, 2006

- National Endowment for the Arts, 1997

- Stegner Fellowship, 1993–1995

Biography

The youngest of three sons, David Biespiel—pronounced buy-speel—attended Beth Yeshurun, the oldest Jewish school in Houston. Reared in a family that valued athletic excellence (one brother was a member of the United States Gymnastics team), he competed in the U.S. Diving Championships against Olympians Greg Louganis and Bruce Kimball, and later coached and developed regional and national champions and finalists in diving. In 1982 he moved to Boston on a diving scholarship at Boston University. In 1989 he moved to Washington, D.C., where he studied with Stanley Plumly at the University of Maryland, as well as with Michael Collier and Phillis Levin. He later held a Stegner Fellowship in Poetry Stanford University.

Career

David Biespiel has been called "a big thinker, a doer, and a hard-charging literary force".[1] Living in Boston in the early 1980s, Biespiel was one of the central figures of Glenville, a nexus of young activists, artists, educators, conservationists, musicians, and writers. He began publishing poems and essays in 1986 after moving to remote Brownsville, Vermont. From 1988 to 1993 he lived and wrote in Washington, D.C., and from 1993 to 1995 in San Francisco. He has lived in Portland, Oregon, since 1995.

He is a contributor to American Poetry Review, The New Republic, The New Yorker, Poetry, and Slate, and many literary journals. After reviewing poetry for nearly fifteen years in journals and newspapers, including in Bookforum, The Washington Post, and The New York Times, he was appointed the poetry columnist for The Oregonian in January 2003. His monthly column, which ended in September 2013,[2] was the longest running newspaper column on poetry in the United States. In 2015 he began a series of reviews for American Poetry Review.

In 1999, he founded the Attic Institute of Arts and Letters.[3] An independent literary studio, the institute began as the Attic Writers' Workshop and was established as a haven for writers and a unique knowledge studio dedicated to engaging ways to create, explore, and innovate, to generate and participate in important and lively conversation, and to reflect on ideas, the imagination, and civic life, as well as on artistic, cultural, and social experience. With its writers' workshops and individual consultations—as well as groundbreaking programs that have initiated new ways to study creative writing, such as the Atheneum and the Poets Studio—the Attic Institute has become the focal point for a vibrant literary community in Portland. Writers have seeded collaborations, writing groups, magazine start-ups, and literary friendships. They have signed with publishers and agents, been accepted into residencies and graduate programs, and embarked on literary enterprises of their own. Willamette Week named the Attic Institute the most important school of writers in Portland. The website Bustle hailed the Attic Institute as one of the best writing centers in the U.S. Faculty and Teaching Fellows at the Attic Institute have included: Marc Acito, Matthew Dickman, Merridawn Duckler, Emily Harris, Karen Karbo, Elinor Langer, Jennifer Lauck, Lee Montgomery, Whitney Otto, Paulann Petersen, Jon Raymond, G. Xavier Robillard, Elizabeth Rusch, Kim Stafford, Cheryl Strayed, Vanessa Veselka, Emily Whitman, Wendy Willis, Peter Zuckerman, and others.[4]

In 2005 he was named editor of Poetry Northwest— one of the nation's oldest magazines devoted exclusively to poetry. Appointed by the University of Washington, Biespiel moved the magazine's offices to Portland, and is widely credited with reviving the magazine to national prominence. He served as editor until 2010.[5]

During 2008–2012 Biespiel was a regular contributor to The Politico's Arena, a cross-party, cross-discipline daily conversation about politics and policy among current and former members of Congress, governors, mayors, political strategists and scholars that included Dean Baker, Gary Bauer, Paul Begala, Mary Frances Berry, Bill Bishop, Dinesh D'Souza, Melissa Harris-Perry, Stephen Hess, Celinda Lake, Thomas E. Mann, Mike McCurry, Aaron David Miller, Grover Norquist, Christine Pelosi, Diane Ravitch, Larry J. Sabato, Craig Shirley, Michael Steele, Fred Wertheimer, Darrell M. West, Christine Todd Whitman, and others.[6]

In 2009 he helped formed the trio Incorporamento. The artistic group includes Oregon Ballet Theater principal dancer Gavin Larsen and musician Joshua Pearl. Incorporamento debuted its first pieces of original dance, music, and poetry at Portland Center Stage on January 10, 2010, at the Fertile Ground Festival. Returning to the festival the following year, Incorporamento performed "A Ghost in the Room with You" at Conduit Studios, which Oregon Arts Watch hailed as "deep, complex, and satisfying". Incorporamento premiered "Ships of Light" on November 1, 2013 at BodyVox Dance Center in Portland, Oregon. The original performance focused on the passage of time as a sequence of daily rituals that become one's yearly experience and is highlighted by Larsen's riveting choreography and dance in "Uncharted Territory" and Biespiel and Pearl's free verse and musical reinterpretation of George Gershwin's "Summertime".

In 2009 he was elected by the membership of the National Book Critics Circle to the Board of Directors and served as a judge for the annual NBCC book awards. He was reelected in 2012 for a second term. During 2012–2014 he was chair of its award committee on Poetry. In 2018 he was named a finalist for the Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing.

In 2012 he began writing Poetry Wire for the Rumpus Magazine.[7] His new column on poetry quickly gained attention with Biespiel's criticism of the influence of Ezra Pound and postmodernism, satires of po-biz foibles, "discovery" of the found poetry of U.S. General David Petraeus, a defense of the writer Meg Kearney against attacks by Pulitzer Prize winner Franz Wright, as well as provocative pieces about poetry, politics, and cultural issues such as the fate of poets in the Syrian civil war, the Newtown massacre, American poetics, and poetry's role in American life. Recent sequences include Poet's Journey about the poet's relationship to both modern life and the imagination and also a Whitman Notebook, a meditation on reading Walt Whitman's "Song of Myself" during the 200th anniversary of Whitman's birth.

He has taught creative writing and literature throughout the United States, including at George Washington University, University of Maryland, Stanford University, Portland State University, and Lynchburg College as the Richard H. Thornton Writer in Residence, and during 2007–2011 as poet-in-residence in the fall at Wake Forest University. He currently divides his teaching between the Rainier Writer's Workshop M.F.A. Program at Pacific Lutheran University and the graduate program in creative writing in the School of Writing, Literature, and Film at Oregon State University where he is the university's Poet-in-Residence.

Poetry

David Biespiel is one of his generation's most inventive poets. The hallmark of his poems is an intricate blending of traditional elements within an eclectic free verse style that has earned him praise as a "true poetic innovator".[8]

Republic Café: Republic Café, published in 2019, is a single sequence, arranged in fifty-four numbered sections, that details the experience of lovers in Portland, Oregon, on the eve and days following September 11, 2001. Publishers Weekly praised the book for being a meditation "on love during a time of violence, tallying what appears and disappears from moment to moment." The Rumpus welcomed the book for the way it "creates a kind physical and metaphysical intimacy that feels quite rare in the present moment of American poetry." David St. John writes: "I was unprepared for the true enormity of the scope of this remarkable, deeply moving and consistently compelling new book. With his usual elegance and formal grace, David Biespiel's Republic Café strikes me as being both expansive and deeply forgiving of human acts, however horrible." Plume: "Republic Café seems effortlessly ambitious in scope. Biespiel explores broad, overarching themes that few poets are willing to meet head on today. Though the story background is horrific, the poem is hopeful. . . . It reminds us that love is key to our survival and that forgiveness is a requirement, not an option. Republic Café is the graceful and moving work of a poet at the top of his game. It should be part of your permanent library.” "Biespiel's finest book of poems to date," says David Baker, "Republic Café builds on Biespiel's strengths as a lyric poet with a social conscience, a latter-day Romantic in a skeptical time. Republic Café is both personal and political, much in the manner of its evident forebear, Walt Whitman. This is a postmodernist's Romanticism." Laura Kasischke adds: "David Biespiel reinvents poetry in Republic Café by mating a love poem with a historical narrative. A moment in time, a self within it―together the size of a pinprick―are revealed here to be as infinite as the universe. Nothing escapes the net this poet casts out with his powerful form and original vision. Transcendent, mysterious, and as supernatural as it is completely human, this is poetry that transforms the reader."

Charming Gardeners: Charming Gardeners, published in 2013, marks another shift in Biespiel's undertaking in probing the intersection between traditional and invented forms and harkens back to the unfurled expansive style of Shattering Air. Library Journal's starred review noted that "Biespiel's poems echo Walt Whitman [and] can be prophetic." The collection was welcomed by Publishers Weekly as a book of "unguarded friendship, attentive to a poet with much to say ... his looks at U.S. history are at once informative and grand." The review lauds the book's "meditations on politics, from a poet known for his prose about culture and politics" and praises the poems as "successors to Richard Hugo' 31 Letters and 13 Dreams." City Arts commented that the poems in Charming Gardeners "weave together the beauty of nature and the existential trials of humanity". Open Books noted that to "open Charming Gardeners is to unwrap a packet of letters, all written by an attentive and contemplative poet". In her interview with David Biespiel for NPR's State of Wonder, April Baer noted the "subjects of Biespiel's new book of poetry, Charming Gardeners, are friends of his from every corner of the U.S., including his wife and son, writers like Christian Wiman, and intellectual adversaries like William F. Buckley and Cesar Conda. Born in Oklahoma and raised in Texas, you can hear just a ghost of a drawl when Biespiel speaks. But when he reads his poetry, that ghost takes form, both in Biespiel's accent and in his invocations of places like Confederate battlefields and West Virginian cemeteries."[9] In New Books in Poetry, John Ebersole introduces his interview with Biespiel observing that in "many ways, Biespiel's journey is America's, where the road is both a symbol of arrivals, but also departures, and in between is solitude ... his poems encompass each of us, socially and politically, by illuminating our nation's contradictory character: a longing for enchantment in a disenchanted world."

The Book of Men and Women: The Book of Men and Women, Biespiel's next book, continues the expressionistic style so prevalent in Wild Civility. The book was selected by the Poetry Foundation as one of the best books of the year for 2009.[10] The book also was honored with the Stafford/Hall Award for Poetry and Oregon Book Award from Literary Arts in 2011,[11] selected by Robert Pinsky, who praised Biespiel as a poet who had "mastered his own grand style. What's more, he deploys it for work: the cascade of invention, the big eclectic lexicon and rich figures of sound are not for show, but for doing work, living up to this ambitious title: The Book of Men and Women. On the one hand, this is language soaring up above the earth, teasing its way beyond stolid paraphrase, but on the other hand it is always connected to "the groan of the unfinished garden" — the last phrase of 'Man and Wife.' The intricate, rich but discordant music has a mocking jauntiness hard to forget, self-aware and self-critical, and in spite of itself having a jaunty if wincing good time, as in 'The Crooner': 'It's maddening,/ This measly rigmarole he's come to, this voice, his crazy quilt.// Unadvised, pleased with the take-home pay of it all, teetotalling,/ He glimmers like a forgotten mouth, aims for the deep end of all that's muddy and dim,/ And mocks the majesty of ringers. Same for the hay-high dandies.'"[12] In his essay-review, "A Good Long Scream", published in Poetry, critic Nate Klug praises Biespiel's "ferocious" imagination and his "quirky, alliterative idiom that produces many memorable phrases.... A reviewer of Cormac McCarthy once called the novelist's work 'a good, long scream in the ear.' The Book of Men and Women, with its rogue characters and laundry lists of loss, pursues a similar effect. Biespiel's bristly voice is the first thing most readers will note, and indeed his writing is successful to the degree that this voice performs—that is, remains rhetorically compelling—throughout the course of the poem."[13]

Wild Civility: Wild Civility was published in 2003 just following the publication of the limited edition book, Pilgrims & Beggars. The two books mark a dramatic shift in both style and formal intensity from the poems in Shattering Air. The achievement of "Wild Civility" is Biespiel's invention of an original "American sonnet". These explosive, innovative nine-line monologues are variations on the English and Italian sonnet. The poems rumble across the page with a jazzy linguistic verve that recalls the paintings of Jackson Pollock and the poetry of Walt Whitman. Writing in Poetry (magazine), David Orr noted how the poems "shuffle between registers and tones, use deliberately mismatched diction", and cited "Biespiel's best poems in this untraditional vein" as the ones with the "clearest connection to lyric poetry".[14] Michael Collier praised the book for demonstrating "the pure and powerful recombinant energy of language that is the essence of lyric poetry".[15]

Shattering Air: Published in 1996 when Biespiel was 32, Shattering Air is a book of autobiographical portraits composed in variegated blank verse. It was one of the last books published by the iconic American poetry editor and founder of BOA Editions, Al Poulin, Jr.[16] "It is a test of the seamlessness of his art that David Biespiel so constantly finds the 'ruminant undercurrents' of his subjects without ever sacrificing their actuality,"[17] Stanley Plumly wrote in his Introduction to the book. "And it is all the more remarkable in a first book that this undercurrent — what Wordsworth once called 'the imminent soul in things' — should so effectively supersede appearances. If this sounds a grand prescription, in Biespiel's hands it is not." Publishers Weekly characterized the debut collection as "sustained by a search for transcendent, intuitive truths". From Chelsea: "Biespiel has a gift for transformation. He can make a command sound like an incantation. He can create psalm-like beauty from the repetition of a simple phrase. One must note the instances of raw brilliance." A.V. Christie praised the book in The Journal for being "poems of quiet grandeur and nobility [that] bring to mind an out-of-the-self Keatsian sensibility".

Nonfiction

The Education of a Young Poet: Published in 2017. Named a Best Books for Writers by Poets & Writers. "Biespiel's supple memoir of becoming a poet will surely inspire other writer," wrote Publisher's Weekly in a starred review. In Library Journal's starred review, the reviewer praised the book as a "lyrical fugue of a memoir [that] charmingly mixes meditation and memories, spans generations and oceans." More praise followed. Poets & Writers: "Woven throughout the memoir are inspiring anecdotes about leading a literary life, including insights into the craft of writing and the power of language in everyday life and in literature." The Rumpus: "The Education of a Young Poet is filled with unassuming but riveting observations...that show not only how important poetry is to daily life but also how it's, in fact, inextricable from life. This book will make you appreciate poetry more. And if you're a poet, it will make you proud to be one." Los Angeles Review of Books: "[W]ith that capacious energy of the best American writing, Biespiel chronicles a range of seemingly disconnected things — screaming nighthawks, Boston bookstores, the Roman poet Catullus...his metaphors are often memorable because he doesn't just make them, he dives in and flushes them out. As a result, a number of scenes flow breathlessly across the page...[to] convey a sense of mystery, suggest unexpected connections, evoke emotional riches." Kirkus Reviews: "Tracing the evolution of a poet's passion...lyrical, affectionate anecdotes about friends and family round out the author's graceful reflections on creativity."

A Long High Whistle: Selected Columns on Poetry: Published in 2015. Received the 2016 Frances Fuller Victor Award for General Nonfiction and the Oregon Book Award from Literary Arts. Library Journal's starred review praises the book for being a "perfect introduction to how to read a poem; Biespiel doesn't tell us how to read, instead he simply shows us. One of the best books about reading poetry you will ever find". New Pages called the collection "quotable and useful", and Bostonia concurred: "For people reluctant to do the intellectual heavy lifting they believe poetry demands, the only thing more inaccessible than the form itself is what's written about poetry. But both the novice and the aficionado will delight in Biespiel's A Long High Whistle.... Biespiel's warmth and respect for his readers is reflected in prose that, like William Zinsser's classic On Writing Well, makes us care about, and be alert to, the wonders of metaphor."

Every Writer Has a Thousand Faces: A Tenth Anniversary Edition, revised and updated, with a Foreword by novelist Chuck Palahniuk will be published in early 2020. Originally published in 2010. Hazel & Wren magazine called the book "a well-spring of ideas for how to jump start the creative process, valuable examples of athletic and visual artists who exercise this proposed method, and, perhaps most importantly, OODLES of empathy for the writer/artist who is battling their own stuck process and potentially self-doubt or frustration." The book "does for the creative process," Marjorie Sandor says, "what Strunk and White did for our approach to grammar and style."

Poetry and democracy

In 2010, Biespiel sparked a national debate about the relationship between poets and democracy with the publication of his essay, "This Land Is Our Land",[18] in Poetry. Writing about the importance of citizen-poets, Biespiel contends that:

"Beyond the essential concern for writing poems, the poet's role must also include public participation in the life of the Republic. By and large, poets have lived by the creed that this sort of exposure can be achieved only through the making of poems, that to be civically engaged in any other fashion would poison the creative self. But while poems are the symbolic vessels for the imagination and metaphor, there are additional avenues to speak to the tribe. The function of the poet may be to mythologize experience, but another function is to bring a capacity for insight—including spiritual insight—into contact with the political conditions of existence. The American poet must speak truth to power and interpret suffering. And just as soon as the American poet actually speaks in public about civic concerns other than poetry, both American poetry and American democracy will be better off for it."[18]

Controversy spread from the Poetry Foundation[18] to The Huffington Post,[19] with Garrett Hongo, Stephen Burt, Terrance Hayes, Daisy Fried and others commenting on the essay online and in print. While Terrance Hayes lauded the essay's intentions by writing that "I'm absolutely interested in poets who are doing exactly what Biespiel proposes," critic Stephen Burt contended that Biespiel's claims are "bad for our poetry".[20]

In the March 11, 2010 online edition of The New York Times, Gregory Cowles covered the ongoing debate and commented, "I'm struck by the plaintive note that hums just beneath Biespiel's argument: as much as it's a rousing call to political action, his essay is also an eloquent statement of the anxiety of irrelevance." Cowles compares Biespiel's concerns to similar ones expressed by fiction writer David Foster Wallace: "For Biespiel, poetry doesn't matter because poets aren't political enough. For Wallace, poetry doesn't matter because poets have neglected the common reader."[21]

Responding to the controversy, Biespiel wrote in the July/August 2010 issue of Poetry (magazine): "I hold that poets retain a special stature in the human community. The greatest title in a democracy is neither president nor poet. It is citizen. And so I stand with those who see not just the nobility of, but the pragmatic need for, fusing the citizen with the poet."[22]

On December 2, 2010, "This Land Is Our Land" was cited by the Poetry Foundation as one of the top read articles on its website.[23]

Biespiel took up a similar strain of this subject in The Rumpus in his January 15, 2014, Poetry Wire column titled, "Something More Than Style". Where "This Land Is Our Land" argued for poets to be open to engaging the body politic as individuals, "Something More Than Style" wondered if conceptualism held poets back from engaging the social and political world more generally in their poems. He writes:

"While many of the world's poets are deeply preoccupied with war and hierarchy, with exploitation and power, there is a pervasive sinisterlessness in American poetry. There is hash and rehash of the quotidian, an alarmlessness, a niche of the nada. Deftness has become a substitute for compassion. Style a stand in for thinking and feeling. Self-destructive forms are now glorified over measured insight.... Because so many poets face extreme violent risks in the world — and I do not mean the false risks extolled in America's writing workshops — there is a need for American poets to own up to and reject our sheer terrorlessness, to reject aesthetic fetishization in favor not only of examining the barbarism of human experience but also in being less existential and more confrontational of our own complicity in favoring an art of theory over an art of life."

In the comments, Canadian poet Sina Queyras countered, "insight is not teachable. Form and style are.... I would rather encounter a conceptual poem from a poet with a lack of insight than a lyric poem from a poet with a lack of insight."

On February 23, 2015, Biespiel's column, "Why Jihadists Love Postmodern Poetry", published in The Rumpus in the aftermath of the ''Charlie Hebdo'' shooting in Paris ignited debate about the dangers of "a world overflowing with cynicism about the meaning of language and the power of metaphor". Charging that the jihadist's violent murder in downtown Paris is postmodernism in the extreme, Biespiel writes:

"Now I know the differences between violent, murdering extremism performed in the public square and poetic experimentation performed in the literary square. There is no moral equivalency between cold-blooded killers and literary-bound poets who practice an art of free-flowing creations constructed of a language that largely points to itself. When it comes to free speech, I'm an absolutist. I believe that free poetic speech should represent a front line — an avant-garde, one might say — against totalitarianism of every kind including, in Salman Rushdie's phrase, 'religious totalitarianism'.... But let's not kid ourselves either. The differences may be measurable but the phenomena are not unrelated. Jihadists have adopted the zeal of deconstructing language, meaning, and metaphor ... [with] jihadi jingles and their hip-hop-esque scratching of modern-day military operations with ancient images of martyrdom. Next time you wonder what oppression-loving, surface-to-air-missile-toting reactionaries with their entrenched tribal values of honor and shame stand for regarding the transparency of speech and language, have a listen to the way they love to glom onto the propaganda of anti-globalism.... When the world feels like it's fragmenting into a million pieces, I don't look for poetry of fragmentation. I don't look for an aesthetic of discombobulation. Instead, I look for poetry of persuasive metaphor and communion and renewal ... and I look for poetry that contains at least the possibility, necessity, and essential spirit of coherent empathy and understanding.... Now that's just me because I feel that practitioners of neomodernist and postmodernist poetry would easily argue through their poems that even fanatical jihadism is a project of postmodernism for its refusal of modernity as a battleground against Western imperialism and global markets. If only this vision of postmodernist jihad didn't include preventing merchants in repressive countries from rejoining the world marketplace. If only this vision of postmodernist jihad didn't include attacks on schools, especially schools for girls. If only this vision of postmodernist jihad didn't include, month after month, acts of kidnapping, rape, bombing, stabbings, shootings, and massacres. If only once we would hear violent religious fanatics drop the doctrinal mask that never allows for compromise to say one word, just one word in favor of pluralism or individual liberty that is actually the foundation of experimental art and literature and music. No, these postmodern jihadists favor and take advantage of disruption and fragmentation. They favor the denial of authority and the reduction of content to an austere minimum. They regard life and art as unreal. They repudiate harmony and promote the arbitrary in order to avoid responsibility. And they create chaos and disorder so that zealots can rush in.[24]

The Kenyon Review published several essays in response by G. C. Waldrep, Fady Joudah, and others. The following June The New Yorker published the essay, "Battle Lines", by Robyn Creswell and Bernard Haykel, asking the question, "If you want to understand the jihadis? Read their poetry.... It is impossible to understand jihadism—its objectives, its appeal for new recruits, and its durability—without examining its culture. This culture finds expression in a number of forms, including anthems and documentary videos, but poetry is its heart. And, unlike the videos of beheadings and burnings, which are made primarily for foreign consumption, poetry provides a window onto the movement talking to itself. It is in verse that militants most clearly articulate the fantasy life of jihad."[25]

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 22, 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Poetry: Afresh and refreshed". The Oregonian. September 21, 2013.

- "History". The Attic Institute of Arts and Letters. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 31, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 13, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Arena Profile: David Biespiel". Politico.

- "Posts by: David Biespiel". The Rumpus.

- "Readings Listings". The Portland Mercury. December 11, 2003. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved 2013-12-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "The Book of Men and Women". University of Washington Press. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- "Literary Arts". Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- Pinsky, Robert (May 23, 2011). "Judge's Comments in Poetry". Paper Fort. Literary Arts. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- Klug, Nate (January 2010). "A Good, Long Scream". Poetry. Poetry Foundation. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- Orr, David. "Review: Wild Civility by David Biespiel". Poetry. 184: 310–312. JSTOR 20606696.

- "Wild Civility". University of Washington Press. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- "Al Poulin, Founding Editor Of Poetry House, Dies at 58". Obituary. The New York Times. June 10, 1996.

- Plumly, Stanley (1996). Shattering Air. BOA. ISBN 9781880238356.

- Davied Biespiel (April 30, 2010). "This Land Is Our Land". Poetry.

- Kunhardt, Jessie (May 3, 2010). "Why Aren't Poets More Politically Active?". The Huffington Post.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 11, 2011. Retrieved 2010-12-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Cowles, Gregory (May 11, 2010). "Does Poetry Matter?". The New York Times Papercuts blog.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 11, 2011. Retrieved 2010-12-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "The 15 most-read Poetry Foundation & Poetry magazine articles of 2010". Poetry Foundation. December 2, 2010.

- David Biespiel (February 3, 2015). "David Biespiel's Poetry Wire: Why Jihadists Love Postmodern Poetry". The Rumpus.

- Robyn Creswell; Bernard Haykel (2015). "Want to Understand the Jihadis? Read Their Poetry". The New Yorker (June 8th & 15th ed.). Retrieved March 24, 2018.