Dark-eyed junco

The dark-eyed junco (Junco hyemalis) is a species of the juncos, a genus of small grayish American sparrows. This bird is common across much of temperate North America and in summer ranges far into the Arctic. It is a very variable species, much like the related fox sparrow (Passerella iliaca), and its systematics are still not completely untangled.

| Dark-eyed junco | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female dark-eyed junco (Junco hyemalis hyemalis) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Passerellidae |

| Genus: | Junco |

| Species: | J. hyemalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Junco hyemalis | |

| |

| Approximate range in North America Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range | |

| Synonyms | |

(but see text) | |

Description

Adults generally have gray heads, necks, and breasts, gray or brown backs and wings, and a white belly, but show a confusing amount of variation in plumage details. The white outer tail feathers flash distinctively in flight and while hopping on the ground. The bill is usually pale pinkish.[2]

Males tend to have darker, more conspicuous markings than the females. The dark-eyed junco is 13 to 17.5 cm (5.1 to 6.9 in) long and has a wingspan of 18 to 25 cm (7.1 to 9.8 in).[2][3] Body mass can vary from 18 to 30 g (0.63 to 1.06 oz).[2] Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 6.6 to 9.3 cm (2.6 to 3.7 in), the tail is 6.1 to 7.3 cm (2.4 to 2.9 in), the bill is 0.9 to 1.3 cm (0.35 to 0.51 in) and the tarsus is 1.9 to 2.3 cm (0.75 to 0.91 in).[4] Juveniles often have pale streaks and may even be mistaken for vesper sparrows (Pooecetes gramineus) until they acquire adult plumage at 2 to 3 months. But junco fledglings' heads are generally quite uniform in color already, and initially their bills still have conspicuous yellowish edges to the gape, remains of the fleshy wattles that guide the parents when they feed the nestlings.

The song is a trill similar to the chipping sparrow's (Spizella passerina), except that the red-backed junco's (see below) song is more complex, similar to that of the yellow-eyed junco (Junco phaeonotus). The call also resembles that of the black-throated blue warbler's, which is a member of the New World warbler family.[5] Calls include tick sounds and very high-pitched tinkling chips.[6] It is known among bird language practitioners as an excellent bird to study for learning "bird language."

A sample of the song can be heard at the USGS web site here (MP3) or at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology web site here.

Taxonomy

The dark-eyed junco was described by Linnaeus in his 1758 Systema naturae as Fringilla hyemalis. The description consisted merely of the laconic remark "F[ringilla] nigra, ventre albo. ("A black 'finch' with white belly"), a reference to a source, and a statement that it came from "America".[7]

Linnaeus' source was Mark Catesby who described the slate-colored junco before binomial nomenclature as his "snow-bird", moineau de neige or passer nivalis ("snow sparrow") thus:

"The Bill of this Bird is white: The Breast and Belly white. All the rest of the Body black; but in some places dusky, inclining to Lead-color. In Virginia and Carolina they appear only in Winter: and in Snow they appear most. In Summer none are seen. Whether they retire and breed in the North (which is most probable) or where they go, when they leave these Countries in Spring, is to me unknown." [italics in original][8]

The slate-colored junco is unmistakable enough to make it readily recognizable even from Linnaeus' minimal description.

Junco is the Spanish for rush, from Latin juncus.[9] Its modern scientific name means "winter junco", from Latin hyemalis "of the winter".[10]

Subspecies

The several subspecies make up two large groups and three to five small or monotypic ones. The five basic groups were formerly considered separate species (and the Guadalupe junco frequently still is), but they interbreed extensively in areas of contact. Birders trying to identify subspecies are advised to consult detailed identification references.[6][11]

Slate-colored juncos

- J. h. hyemalis

- J. h. carolinensis

- J. h. cismontanus (perhaps an Oregon x slate-colored cross) (also known as "Cassiar")

This group has dark slate-gray head, breast and upperparts. Females are brownish gray, sometimes with reddish-brown flanks.[6] They breed in North American taiga forests from Alaska to Newfoundland and south to the Appalachian Mountains, wintering through most of the United States. They are relatively common across their range.

White-winged junco

- J. h. aikeni

The white-winged junco has a medium-gray head, breast, and upperparts with white wing bars. Females are washed brownish. It has more white in the tail than the other forms. It is a common endemic breeder in the Black Hills area of South Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Montana, and winters south to northeastern New Mexico.[2][6]

Oregon juncos

- J. h. montanus

- J. h. oreganus

- J. h. pinosus

- J. h. pontilis

- J. h. shufeldti

- J. h. thurberi

- J. h. townsendi

These have a blackish-gray head and breast with a brown back and wings and reddish flanks, tending toward duller and paler plumage in the inland and southern parts of its range.[11] Oregon juncos are less commonly referred to as brown-backed Dark-eyed juncos. This is the most common form in the west, found in the Pacific coast mountains from southeastern Alaska to extreme northern Baja California, wintering to the Great Plains and northern Sonora. An unresolved debate exists as to whether this large and distinct group is a full species.

Pink-sided junco

- J. h. mearnsi

Often considered part of the Oregon group, it has a lighter gray head and breast than the Oregon group with contrasting dark lores. The back and wings are brown. It has pinkish-cinnamon color that is richer and covers more of the flanks and breast than in Oregon juncos. It breeds in the northern Rocky Mountains from southern Alberta to eastern Idaho and western Wyoming; it winters in central Idaho and nearby Montana and from southwestern South Dakota, southern Wyoming, and northern Utah to northern Sonora and Chihuahua.[11]

Gray-headed junco

- J. h. caniceps

This subspecies is essentially rather light gray on top with a rusty back. It breeds in the southern Rocky Mountains from Colorado to central Arizona and New Mexico, and winters into northern Mexico.[2][6]

Red-backed junco

- J. h. dorsalis

Often included with J. h. caniceps as 'gray-headed juncos, it differs from the gray-headed junco proper in having a more silvery bill[11] with a dark upper mandible,[2][6] a variable amount of rust on the wings, and pale underparts. This makes it similar to the yellow-eyed junco (J. phaeonotus) except for the dark eye. It is found in the southern mountains of Arizona and New Mexico.[6] It does not overlap with the yellow-eyed junco in breeding range.

Guadalupe junco

- J. h. insularis

The extremely rare Guadalupe junco is also considered part of this species by some authors, including the IUCN, which restores it to subspecies status in 2008.[12][13] Other authors consider it a species in its own right – perhaps a rather young one, but certainly this population has evolved more rapidly than the mainland juncos due to its small population size and the founder effect.

Ecology

Their breeding habitat is coniferous or mixed forest areas throughout North America. In otherwise optimal conditions they also utilize other habitat, but at the southern margin of its range it can only persist in its favorite habitat.[14] Northern birds migrate further south, arriving in their winter quarters between mid-September and November and leaving to breed from mid-March onwards, with almost all gone by the end of April or so.[14][15] Many populations are permanent residents or altitudinal migrants, while in cold years birds may choose to stay in their winter range and breed there.[14] For example, in the Sierra Nevada of eastern California, J. hymealis populations will migrate to winter ranges 5,000–7,000 feet (1,500–2,100 m) lower than their summer range. In winter, juncos are familiar in and around towns, and in many places are the most common birds at feeders.[2] The slate-colored junco is a rare vagrant to western Europe and may successfully winter in Great Britain, usually in domestic gardens.

These birds forage on the ground. In winter, they often forage in flocks that may contain several subspecies. They mainly eat insects and seeds.

They usually nest in a cup-shaped depression on the ground, well hidden by vegetation or other material, although nests are sometimes found in the lower branches of a shrub or tree. The nests have an outer diameter of about 10 cm (3.9 in) and are lined with fine grasses and hair. Normally two clutches of four eggs are laid during the breeding season. The slightly glossy eggs are grayish or pale bluish-white and heavily spotted (sometimes splotched) with various shades of brown, purple or gray. The spotting is concentrated at the large end of the egg. The eggs are incubated by the female for 12 to 13 days. Young leave nest between 11 and 14 days after hatching.

References

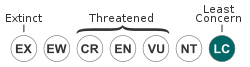

- BirdLife International (2012). "Junco hyemalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology (2002): Bird Guide – Dark-eyed junco. Retrieved 2007-JAN-20.

- Rising, J.D. (2010) A Guide to the Identification and Natural History of the Sparrows of the United States and Canada. Christopher Helm Publishers, London, ISBN 1408134608.

- Sparrows and Buntings: A Guide to the Sparrows and Buntings of North America and the World by Clive Byers & Urban Olsson. Houghton Mifflin (1995). ISBN 978-0395738733.

- "Black-throated Blue Warbler (Dendroica caerulescens)". Birds in Forested Landscapes. Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Sibley, David Allen (2000): The Sibley Guide to Birds. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, pp. 500–502, ISBN 0-679-45122-6

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758): 98.30. Fringilla hyemalis. In: Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (10th ed., vol.1): 183. Laurentius Salvius, Holmius (= Stockholm).

- Catesby, Mark (1731): 36. Passer nivalis. In: The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahamas (vol.1): Spread 65.

- "Junco". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London, United Kingdom: Christopher Helm. pp. 197, 212. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Dunn, Jon L. (2002). "The identification of Pink-sided Juncos, with cautionary notes about plumage variation and hybridization". Birding. 34 (5): 432–443.

- BirdLife International (2008) Guadalupe junco species factsheet. Retrieved 2008-MAY-26.

- BirdLife International (2008): 2008 IUCN Redlist status changes Archived August 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2008-MAY-23.

- Ohio Ornithological Society (2004): Annotated Ohio state checklist Archived July 18, 2004, at the Wayback Machine.

- Henninger, W.F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60.

Further reading

Book

- Nolan, V., Jr., E. D. Ketterson, D. A. Cristol, C. M. Rogers, E. D. Clotfelter, R. C. Titus, S. J. Schoech, and E. Snajdr. 2002. Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis). In The Birds of North America, No. 716 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

Theses

- Dolan PM. Ph.D. (1982). DOMINANCE, AGGRESSION, AND SOCIAL POWER IN WINTER FLOCKS OF THE DARK-EYED JUNCO (JUNCO HYEMALIS). University of Montana, United States – Montana.

- Swanson DL. Ph.D. (1990). Seasonal thermoregulation in the dark-eyed junco (Passeriformes:Junco hyemalis). Oregon State University, United States – Oregon.

- Terrill SB. Ph.D. (1986). THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SOCIAL DOMINANCE, MIGRATORY RESTLESSNESS AND ENERGETICS IN THE DARK-EYED JUNCO, JUNCO HYEMALIS, (L) (BIRDS, PHYSIOLOGY, DISPERSAL). State University of New York at Albany, United States – New York.

Articles

Morphology

- Mulvihill RS & Chandler CR. (1990). The Relationship between Wing Shape and Differential Migration in The Dark-Eyed Junco. Auk. vol 107, no 3. pp. 490–9

- Mulvihill RS & Chandler CR. (1991). A COMPARISON OF WING SHAPE BETWEEN MIGRATORY AND SEDENTARY DARK-EYED JUNCOS (JUNCO-HYEMALIS). Condor. vol 93, no 1. pp. 172–5

- Neal, Joseph C. (2003). The Junco Challenge: A Genuine Pink-sided Junco from Arkansas and Some Look-alikes Birding 35(2): 132–6

Behavior

- Allan TA. (1979). Parental Behavior of a Replacement Male Dark-Eyed Junco Junco-Hyemalis. Auk. vol 96, no 3. pp. 630–631.

- Baker MC, Belcher CS, Deutsch LC, Sherman GL & Thompson DB. (1981). Foraging Success in Junco Junco-Hyemalis Flocks and the Effects of Social Hierarchy. Anim Behav. vol 29, no 1. pp. 137–142.

- Balph MH. (1979). Flock Stability in Relation to Social Dominance and Agonistic Behavior in Wintering Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis. Auk. vol 96, no 4. pp. 714–722.

- Boysen AF, Lima SL & Bakken GS. (2001). Does the thermal environment influence vigilance behavior in dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis)? An approach using standard operative temperature. J Therm Biol. vol 26, no 6. pp. 605–612.

- Butler RW. (1980). Appropriation of an American Robin Turdus-Migratorius Nest by Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis-Oreganus. Canadian Field Naturalist. vol 94, no 2.

- Caraco T. (1981). ENERGY BUDGETS, RISK AND FORAGING PREFERENCES IN DARK-EYED JUNCOS (JUNCO-HYEMALIS). Behav Ecol Sociobiol. vol 8, no 3. pp. 213–217.

- Clotfelter ED, Schubert KA, Nolan V & Ketterson ED. (2003). Mouth color signals thermal state of nestling dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis). Ethology. vol 109, no 2. pp. 171–182.

- Corbitt C & Deviche P. (2005). Age-related difference in size of brain regions for song learning in adult male dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis). Brain Behavior & Evolution. vol 65, no 4. pp. 268–277.

- Cristol DA. (1992). Food Deprivation Influences Dominance Status in Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis. Anim Behav. vol 43, no 1. pp. 117–124.

- Cristol DA. (1995). Costs of switching social groups for dominant and subordinate dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis). Behavioral Ecology & Sociobiology. vol 37, no 2. pp. 93–101.

- Cristol DA, Nolan VJ & Ketterson ED. (1990). Effect of Prior Residence on Dominance Status of Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis. Anim Behav. vol 40, no 3. pp. 580–586.

- Czikeli H. (1983). Agonistic Interactions within a Winter Flock of Slate-Colored Juncos Junco-Hyemalis Evidence for the Dominants Strategy. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. vol 61, no 1. pp. 61–66.

- Deviche P & Gulledge CC. (1998). Vocal control region volumes of an adult, sexually dimorphic songbird (Junco hyemalis) change seasonally in both sexes. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. vol 24, no 1–2.

- Fretwell S. (1969). Dominance Behavior and Winter Habitat Distribution in Juncos Junco-Hyemalis. Bird Banding. vol 40, no 1. pp. 1–25.

- Goldman P. (1980). Flocking as a Possible Predator Defense in Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis. Wilson Bull. vol 92, no 1. pp. 88–95.

- Goldstein GB & Baker MC. (1984). Seed Selection by Juncos Junco-Hyemalis. Wilson Bull. vol 96, no 3. pp. 458–463.

- Grindstaff JL, Buerkle CA, Casto JM, Nolan V & Ketterson ED. (2001). Offspring sex ratio is unrelated to male attractiveness in dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis). Behav Ecol Sociobiol. vol 50, no 4. pp. 312–316.

- Hill JA, Enstrom DA, Ketterson ED, Nolan V & Ziegenfus C. (1999). Mate choice based on static versus dynamic secondary sexual traits in the dark-eyed junco. Behav Ecol. vol 10, no 1. pp. 91–96.

- Holberton RL, Able KP & Wingfield JC. (1989). Status Signalling in Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis Plumage Manipulations and Hormonal Correlates of Dominance. Anim Behav. vol 37, no 4. pp. 681–689.

- Jawor MM & Ketterson ED. (2003). Dominance status influences breeding success in female dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis). Integr Comp Biol. vol 43, no 6. pp. 861–861.

- Keiser JT, Ziegenfus CWS & Cristol DA. (2005). Homing success of migrant versus nonmigrant dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis). Auk. vol 122, no 2. pp. 608–617.

- Ketterson ED. (1979). Aggressive Behavior in Wintering Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis Determinants of Dominance and Their Possible Relation to Geographic Variation in Sex Ratio. Wilson Bull. vol 91, no 3. pp. 371–383.

- Ketterson ED & Nolan VJ. (1978). Over Night Weight Loss in Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis. Auk. vol 95, no 4. pp. 755–758.

- Ketterson ED & Nolan VJ. (1979). Seasonal Annual and Geographic Variation in Sex Ratio of Wintering Populations of Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis. Auk. vol 96, no 3. pp. 532–536.

- Ketterson ED & Nolan VJ. (1982). The Role of Migration and Winter Mortality in the Life History of a Temperate Zone Migrant the Dark-Eyed Junco Junco-Hyemalis-Hyemalis as Determined from Demographic Analyses of Winter Populations. Auk. vol 99, no 2. pp. 243–259.

- Ketterson ED & Nolan VJ. (1983). Autumnal Zugunruhe and Migratory Fattening of Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis Apparently Suppressed by Detention at the Wintering Site. Wilson Bull. vol 95, no 4. pp. 628–635.

- Lima SL. (1988). Vigilance and Diet Selection a Simple Example in the Dark-Eyed Junco. Canadian Journal of Zoology. vol 66, no 3. pp. 593–596.

- Lima SL, Zollner PA & Bednekoff PA. (1999). Predation, scramble competition, and the vigilance group size effect in dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis). Behav Ecol Sociobiol. vol 46, no 2. pp. 110–116.

- Merritt J & Martin EW. (1987). THE DISTRIBUTION AND TURNOVER OF S-35 METHIONINE AS INFLUENCED BY DIET IN THE DARK-EYED JUNCO (JUNCO-HYEMALIS). Comp Biochem Physiol A-Physiol. vol 88, no 3. pp. 443–445.

- Murphy MT, Bakken GS & Erskine DJ. (1986). METABOLIC RESPONSES OF DARK-EYED JUNCOS (JUNCO-HYEMALIS, AVES) TO TEMPERATURE AND WIND. Am Zool. vol 26, no 4. p. A112-A112.

- Nolan VJ & Ketterson ED. (1983). An Analysis of Body Mass Wing Length and Visible Fat Deposits of Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis Wintering at Different Latitudes. Wilson Bull. vol 95, no 4. pp. 603–620.

- Nolan VJ, Ketterson ED & Wolf L. (1986). Long-Distance Homing by Nonmigratory Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis. Condor. vol 88, no 4. pp. 539–542.

- Rabenold KN & Rabenold PP. (1985). Variation in Altitudinal Migration Winter Segregation and Site Tenacity in Two Subspecies of Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis in the Southern Appalachians USA. Auk. vol 102, no 4. pp. 805–819.

- Rambo TC. (1981). Social Hierarchy and Activity in Caged Flocks of Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis. Ohio Journal of Science. vol 81, no 1. pp. 24–28.

- Rasner CA, Yeh P, Eggert LS, Hunt KE, Woodruff DS & Price TD. (2004). Genetic and morphological evolution following a founder event in the dark-eyed junco, Junco hyemalis thurberi. Mol Ecol. vol 13, no 3. pp. 671–681.

- Roberts EPJ & Weigl PD. (1984). Habitat Preference in the Dark-Eyed Junco Junco-Hyemalis the Role of Photoperiod and Dominance. Anim Behav. vol 32, no 3. pp. 709–714.

- Rogers CM, Nolan V, Jr. & Ketterson ED. (1994). Winter fattening in the dark-eyed junco: Plasticity and possible interaction with migration trade-offs. Oecologia. vol 97, no 4. pp. 526–532.

- Rogers CM, Theimer TL, Nolan VJ & Ketterson ED. (1989). Does Dominance Determine How Far Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis Migrate into Their Winter Range?. Anim Behav. vol 37, no 3. pp. 498–506.

- Shettleworth SJ & Westwood RP. (2002). Divided attention, memory, and spatial discrimination in food-storing and nonstoring birds, black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapilla) and dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis). J Exp Psychol-Anim Behav Process. vol 28, no 3. pp. 227–241.

- Smith KG. (1984). DARK-EYED JUNCO, JUNCO-HYEMALIS, NEST USURPED BY PACIFIC JUMPING MOUSE, ZAPUS-TRINOTATUS. Can Field-Nat. vol 98, no 1. pp. 47–48.

- Smith KG. (1988). CLUTCH-SIZE DEPENDENT ASYNCHRONOUS HATCHING AND BROOD REDUCTION IN JUNCO-HYEMALIS. Auk. vol 105, no 1. pp. 200–203.

- Smith KG & Andersen DC. (1982). Food Predation and Reproductive Ecology of the Dark-Eyed Junco Junco-Hyemalis-Mearnsi in Northern Utah USA. Auk. vol 99, no 4. pp. 650–661.

- Smith KG & Andersen DC. (1985). SNOWPACK AND VARIATION IN REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY OF A MONTANE GROUND-NESTING PASSERINE, JUNCO-HYEMALIS. Ornis Scandinavica. vol 16, no 1. pp. 8–13.

- Soini HA, Schrock SE, Bruce KE, Wiesler D, Ketterson ED & Novotny MV. (2007). Seasonal variation in volatile compound profiles of preen gland secretions of the dark-eyed junco (Junco hyemalis). J Chem Ecol. vol 33, no 1. pp. 183–198.

- Stuebe MM & Ketterson ED. (1982). Fasting in Tree Sparrows Spizella-Arborea and Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis Ecological Implications. Auk. vol 99, no 2. pp. 299–308.

- Stuebe MM & Ketterson ED. (1982). A STUDY OF FASTING IN TREE SPARROWS (SPIZELLA-ARBOREA) AND DARK-EYED JUNCOS (JUNCO-HYEMALIS) – ECOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS. Auk. vol 99, no 2. pp. 299–308.

- Swanson DL. (1990). Seasonal Variation in Cold Hardiness and Peak Rates of Cold-Induced Thermogenesis in the Dark-Eyed Junco Junco-Hyemalis. Auk. vol 107, no 3. pp. 561–566.

- Swanson DL. (1991). SEASONAL ADJUSTMENTS IN METABOLISM AND INSULATION IN THE DARK-EYED JUNCO. Condor. vol 93, no 3. pp. 538–545.

- Terrill SB. (1987). Social Dominance and Migratory Restlessness in the Dark-Eyed Junco Junco-Hyemalis. Behavioral Ecology & Sociobiology. vol 21, no 1. pp. 1–12.

- Theimer TC. (1987). THE EFFECT OF SEED DISPERSION ON THE FORAGING SUCCESS OF DOMINANT AND SUBORDINATE DARK-EYED JUNCOS, JUNCO-HYEMALIS. Anim Behav. vol 35, pp. 1883–1890.

- Thompson DB, Tomback DF, Cunningham MA & Baker MC. (1987). Seed Selection by Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis Optimal Foraging with Nutrient Constraints?. Oecologia. vol 74, no 1. pp. 106–111.

- Vezina F & Thomas DW. (1997). Social rank and the use of nocturnal hypothermia in dark-eyed juncos (Junco hyemalis). Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. vol 78, no 4 SUPPL.

- Vezina F & Thomas DW. (2000). Social status does not affect resting metabolic rate in wintering dark-eyed junco (Junco hyemalis). Physiol Biochem Zool. vol 73, no 2. pp. 231–236.

- Wiedenmann RN & Rabenold KN. (1987). The Effects of Social Dominance between Two Subspecies of Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis. Anim Behav. vol 35, no 3. pp. 856–864.

- Wiley RH. (1990). PRIOR-RESIDENCE AND COAT-TAIL EFFECTS IN DOMINANCE RELATIONSHIPS OF MALE DARK-EYED JUNCOS, JUNCO-HYEMALIS. Anim Behav. vol 40, pp. 587–596.

- Wiley RH & Hartnett SA. (1980). Mechanisms of Spacing in Groups of Juncos Junco-Hyemalis Measurement of Behavioral Tendencies in Social Situations. Anim Behav. vol 28, no 4. pp. 1005–1016.

- Wolf L. (1983). An Experimental Study of Bi Parental Care in the Dark-Eyed Junco Junco-Hyemalis. Am Zool. vol 23, no 4. pp. 930–930.

- Wolf L, Ketterson ED & Nolan VJ. (1988). Parental Influence on Growth and Survival of Dark-Eyed Junco Young Do Parental Males Benefit. Anim Behav. vol 36, no 6. pp. 1601–1618.

- Yasukawa K & Bick EI. (1983). Dominance Hierarchies in Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis a Test of a Game Theory Model. Anim Behav. vol 31, no 2. pp. 439–448.

- Yaukey PH. (1994). VARIATION IN RACIAL DOMINANCE WITHIN THE WINTER RANGE OF THE DARK-EYED JUNCO (JUNCO-HYEMALIS L). J Biogeogr. vol 21, no 4. pp. 359–368.

- Yunick RP. (1976). RATE OF RECTRIX REGROWTH IN DARK-EYED JUNCO. Bird-Banding. vol 47, no 2. pp. 136–140.

Status

- Collins CT. (1987). A Breeding Record of the Dark-Eyed Junco on Santa Catalina Island California USA. Western Birds. vol 18, no 2. pp. 129–130.

- Polder JJW & Voous KH. (1969). Capture of Slate-Colored Junco Junco-Hyemalis in the Netherlands. Limosa. vol 42, no 3–4. pp. 198–200.

Other

- Bears H. (2004). Parasite prevalence in Dark-eyed Juncos, Junco hyemalis, breeding at different elevations. Can Field-Nat. vol 118, no 2. pp. 235–238.

- Brackbill H. (1977). Protracted Prebasic Head Molt in the Dark-Eyed Junco. Bird Banding. vol 48, no 4. pp. 370–370.

- Deviche P, Greiner EC & Manteca X. (2001). Seasonal and age-related changes in blood parasite prevalence in Dark-eyed Juncos (Junco hyemalis, Aves, Passeriformes). J Exp Zool. vol 289, no 7. pp. 456–466.

- Jung RE, Morton ES & Fleischer RC. (1994). BEHAVIOR AND PARENTAGE OF A WHITE-THROATED SPARROW X DARK-EYED JUNCO HYBRID. Wilson Bull. vol 106, no 2. pp. 189–202.

- Ketterson ED & Nolan VJ. (1976). Geographic Variation and Its Climatic Correlates in the Sex Ratio of Eastern Wintering Dark-Eyed Juncos Junco-Hyemalis-Hyemalis. Ecology. vol 57, no 4. pp. 679–693.

- Simmons GA & Sloan NF. (1969). A New Bird Nest Monitoring Technique Inst Event Recorder Hylocichla-Guttata Junco-Hyemalis. American Midland Naturalist. vol 81, no 1. pp. 276–279.

- Weske JS & Bridge D. (1976). INCOMPLETE PRE-BASIC MOLT IN A DARK-EYED JUNCO. Bird-Banding. vol 47, no 3. pp. 276–277.

- Worth CB. (1975). PSEUDOSCORPIONS ON A DARK-EYED JUNCO, JUNCO-HYEMALIS. Bird-Banding. vol 46, no 1. pp. 76–76.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to the dark-eyed junco. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Junco hyemalis |

- Dark-eyed junco ID, including sound and video, at Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Dark-eyed junco - Junco hyemalis - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Juncos: What do we know? An expert discussion of atypical individuals, the fine points of subspecific identification, and the proper understanding of the cismontanus population, from the ID-Frontiers mailing list (January 2004), supplemented with photographs and paintings.

- "Dark-eyed junco media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Dark-eyed junco photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)