Custody Notification Scheme

A Custody Notification Scheme (CNS) is a 24-hour legal advice and support telephone hotline for any Australian Aboriginal person brought into custody, connecting them with lawyers from the Aboriginal Legal Service. It is intended to reduce the high number of Aboriginal deaths in custody by counteracting the effects of institutional racism. Where CNSs have been implemented, there have been dramatic reductions in the numbers of Aboriginal deaths in custody.[1]

The implementation of a CNS in all Australian states and territories was recommendation 224[2] of the 339 recommendations of the 1991 Australian Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody report.

Implementation

Most states and territories did not comply with the CNS recommendation for decades. About 340 Aboriginal people died in custody between the recommendation being made in 1991 and 2015.[3] Between 1991 and 2019, over 400 Aboriginal people have died in custody.[4]

In October 2017, the Australian federal government urged states and territories to implement a CNS.[1]

ACT & NSW

The CNS serving the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and New South Wales (NSW) was established in 2000.[5] It is mandated under NSW law (cl. 37 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Regulation 2016) that officers must inform the CNS, but not in ACT.[6] The service has been successful and has since been cited as a model.[4] In 2016, one Aboriginal person died in custody in NSW; this was the first time an Aboriginal person had died in custody in NSW or the ACT since the CNSs were implemented.[1][4] Police failed to notify the CNS, rather than there being any problem with the service itself.[1][7]

Western Australia

In May 2016, a report recommended that Western Australia stop jailing people for unpaid fines. The report mentioned the death of Ms Dhu. The report was authored by Neil Morgan, Inspector of Custodial Services.[8] In October 2016 Nigel Scullion, the federal Minister for Indigenous Affairs, offered to fund the first three years of implementation for any state that legislated a CNS. The Western Australian government rejected the offer.[9] In March 2017, Dhu's family criticised both the major political parties in Western Australia for not supporting such a scheme. The incumbent Liberal Party voiced their opposition to the program, while the Labor Party said they would consider the scheme though had made no commitments.[7]

Attorney-General of Western Australia, John Quigley, supported such a program, saying "I think it [is] life-saving legislation. I'm sure if they took the late Ms Dhu into custody ... if the Aboriginal Legal Service [had] been contacted on day one it would have been a very different outcome". An online petition calling for the scheme was signed by almost 20,000 people in less than one week.[1]

On 21 May 2018, it was announced that the WA state government had reconsidered the offer from the federal government to fund a CNS, and that the service would be operational by the end of the year. The Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia would operate the service.[10][11][12] Funding negotiations held up the establishment of the service.[13] In November 2018 it was announced the service would be operational in the first half of 2019. The service would cost $952,000 per year, with the Federal Government and State Government contributing $750,000 and $202,000 respectively. ALSWA would employ five lawyers and two support staff to run the service.[14] The ALSWA commenced its CNS service on 2 October 2019. Under the Police Force Amendment Regulations 2019 (WA), Western Australia Police will be required to phone the CNS every time an Aboriginal person, child or adult, is detained in a police facility, regardless of the reason.[15]

Northern Territory

In 2018, the Northern Territory agreed to implement a CNS.[13] The system attracted criticism for exempting protective custody and paperless arrests; for such arrests, police are not required to notify the CNS. There had previously been deaths in NT following exempted types of arrests. There are reports that the CNS legislation was substantially drafted by the police.[4]

Victoria

Victoria had some non-legislative CNS-like requirements in Victoria Police Manual’s instruction 113-1,[4] with notifications are known as known as E* Justice Notifications.[16] In 2018 a proposed law was being reviewed by the Victorian legislature.[13]

On 13 June 2020 it was announced that the federal government would fund the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service (VALS), which already provided an informal version, to deliver an expanded CNS service, after the Parliament of Victoria had passed new legislation. $2.1 million would be provided over three years to establish the service.[17]

Others

In 2018, representatives from South Australia and Queensland argued they already had their own adequate systems in place, while Tasmania said they were considering the system but had not made a decision.[13] As of June 2020, Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania had not yet introduced a formal CNS.[17]

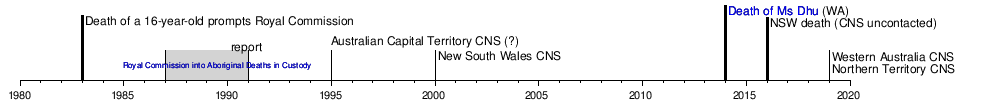

Timeline

References

- Higgins, Isabella (11 October 2017). "States urged to back 'life-saving' policy to prevent Indigenous deaths in custody". ABC News. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "Towards Social Justice? An Issues Paper". austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Wahlquist, Calla (5 December 2015). "Family re-live pain as Ms Dhu inquest searches for answers over death in custody". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Marks, Russell (14 June 2019). "Custody battle". Inside Story. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- "What is the Custody Notification Service?". Aboriginal Legal Service (NSW/ACT) Limited. 1 August 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Custody Notification Service". Australian Government. Australian Law Reform Commission. 19 July 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Wahlquist, Calla (9 March 2017). "Indigenous groups criticise Liberals and Labor in WA over custody policies". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Turner, Rebecca (20 May 2016). "Scrapping jail for fine defaulters will not tackle WA prison overcrowding, report finds". ABC News. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Wahlquist, Calla (20 September 2017). "Ms Dhu's family gets $1.1m payment and state apology over death in custody". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "WA adopts custody hotline in wake of Dhu". National Indigenous Times. 30 May 2018. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018.

- Coade, Melissa (4 June 2018). "WA's new 24-hour welfare line to reduce Aboriginal deaths in custody". Lawyer's Weekly. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Langford, Sam (22 May 2018). "WA Is Finally Taking Steps To Help Prevent Indigenous Deaths In Custody". Junkee. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Wahlquist, Call; Allam, Lorena (29 August 2018). "States failing to take up lifesaving phone service for Indigenous prisoners". Guardian Australia. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- "Joint media statement – Custody Notification Service a step closer to implementation in WA". Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia Limited. 23 November 2018. Archived from the original on 4 December 2018.

- "Custody Notification Service (CNS)". Aboriginal Legal Service. 1 October 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Criminal Law | VALS". vals.org.au. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Wyatt, Ken (13 June 2020). "Custody notification service expands into Victoria". Ministers Media Centre. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

Further reading

- In Safe Custody: Inquiry into Custodial Arrangements in Police Lock-ups (PDF). Western Australia. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Committees.Community Development and Justice Standing Committee. Report 2. Parliament of Western Australia. November 2013. ISBN 978-1-921865-93-0.