Crotalus durissus

Crotalus durissus is a highly venomous pit viper species found in South America. The most widely distributed member of its genus,[2] this species poses a serious medical problem in many parts of its range.[2] Currently, seven subspecies are recognized, including the nominate subspecies described here.[5]

| Crotalus durissus | |

|---|---|

| Venezuelan rattlesnake, C. d. cumanensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Viperidae |

| Genus: | Crotalus |

| Species: | C. durissus |

| Binomial name | |

| Crotalus durissus | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

This large Neotropical rattlesnake grows to a length of 1.5 m (4.9 ft), and rarely to a maximum length of 1.9 m (6.2 ft).[2] It has two distinct stripes starting at the base of the head. Within the lines, the color is lighter than the stripes.

Common names

Common names for this species include: South American rattlesnake,[2] tropical rattlesnake,[4] neotropical rattlesnake,[6] Guiana rattlesnake (previously used for C. d. dryinus).[7] and in Spanish: víbora de cascabel, cascabel, cascabela, and cascavel.[2] In Suriname it is known as Sakasneki.[8]

Geographic range

Crotalus durissus is found in South America except the Andes Mountains. However, its range is discontinuous,[2] with many isolated populations in northern South America, including Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana and northern Brazil. It occurs in Colombia and eastern Brazil to southeastern Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and northern Argentina (Catamarca, Córdoba, Corrientes, Chaco, Entre Rios, Formosa, La Pampa, La Rioja, Mendoza, Misiones, San Juan, San Luis, Santa Fe, Santiago del Estero and Tucumán).[3] Also, it occurs on some islands in the Caribbean, including Morro de la Iguana, Tamarindo and Aruba.[2] The type locality given is "America."[3]

Habitat

It prefers savanna and semi-arid zones. It has been reported to occur in littoral xerophilous scrub, psammophilous and halophilous littoral grassland, thorny xerophilous scrub, tropophilous deciduous and semideciduous scrub, as well as tropophilous semideciduous seasonal forest in the northwest of Venezuela. In the Chaco region of Paraguay, it is found in the drier, sandier areas.[2]

Venom

a.jpg)

Bite symptoms are very different from those of Nearctic species[9] due to the presence of neurotoxins (crotoxin and crotamine) that cause progressive paralysis.[2] Bites from C. d. terrificus in particular can result in impaired vision or complete blindness, auditory disorders, ptosis, paralysis of the peripheral muscles, especially of the neck, which becomes so limp as to appear broken, and eventually life-threatening respiratory paralysis. The ocular disturbances are sometimes followed by permanent blindness.[9] Phospholipase A2 neurotoxins also cause damage to skeletal muscles and possibly the heart, causing general aches, pain, and tenderness throughout the body. Myoglobin released into the blood results in dark urine. Other serious complications may result from systemic disorders (incoagulable blood and general spontaneous bleeding), hypotension, and shock.[2] Hemorrhagins may be present in the venom, but any corresponding effects are completely overshadowed by the startling and serious neurotoxic symptoms.[9] The LD50 value is 0,047 mg/kg(IV), 0,0478 mg/kg(SC), 0,048 mg/kg(IP) and 1,4 mg/kg(IM).[10]

Taxonomy

The Guiana rattlesnake, previously recognized as C. d. dryinus,[3] is now considered a synonym for C. d. durissus. In fact, after the previous nominate subspecies for the C. d. durissus complex became the current nominate for Crotalus simus, which now represents its Mexican and Central American members, C. d. dryinus became the new nominate for the South American rattlesnakes as represented by C. durissus.[2] The subspecies previously known as C. d. collilineatus and C. d. cascavella were moved to the synonymy of C. d. terrificus following the publication of a paper by Wüster et al. in 2005.

Subspecies

| Subspecies[ref 1] | Taxon author[ref 1] | Common name | Geographic range |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. d. cumanensis | Humboldt, 1833 | Venezuelan rattlesnake[ref 2] | Dry lowlands of Venezuela and Colombia |

| C. d. durissus | Linnaeus, 1758 | South American rattlesnake[ref 3] | Coastal savannas of Guyana, French Guyana and Suriname |

| C. d. marajoensis | Hoge, 1966 | Marajon rattlesnake[ref 4] | Known only from Marajo Island, Para State, Brazil |

| C. d. maricelae | García Pérez, 1995 | Bolson arido de Lagunillas, Estado Merida, Venezuela | |

| C. d. ruruima | Hoge, 1966 | Known from the slopes of Mount Roraima and Mount Cariman-Perú in Venezuela (Bolívar). A few specimens have been recorded in Brazil (Roraima).[ref 3] | |

| C. d. terrificus | (Laurenti, 1768) | Cascavel[ref 2] | Brazil south of the Amazonian forests, extreme southeastern Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, northern Argentina |

| C. d. trigonicus | Harris & Simmons, 1978 | Inland savannas of Guyana |

- "Crotalinae". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- Mehrtens JM. 1987. Living Snakes of the World in Color. New York: Sterling Publishers. 480 pp. ISBN 0-8069-6460-X.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW. 2004. The Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Comstock Publishing Associates, Ithaca and London. 870 pp. 1500 plates. ISBN 0-8014-4141-2.

- Brown JH. 1973. Toxicology and Pharmacology of Venoms from Poisonous Snakes. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas. 184 pp. LCCCN 73-229. ISBN 0-398-02808-7.

References

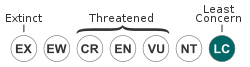

- "Crotalus durissus (Cascabel Rattlesnake, Neotropical Rattlesnake, South American Rattlesnake, Yucatan Rattlesnake)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- Jonathan A. Campbell; William W. Lamar; Edmund D. Brodie (2004). The venomous reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. p. 1500. ISBN 978-0-8014-4141-7.

- Roy W. MacDiarmid (1999). Snake Species of the World. ISBN 978-1-893777-00-2.

- Mehrtens JM. 1987. Living Snakes of the World in Color. New York: Sterling Publishers. 480 pp. ISBN 0-8069-6460-X.

- "Crotalus durissus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 28 November 2007.

- U.S. Navy. 1991. Poisonous Snakes of the World. US Govt. New York: Dover Publications Inc. 203 pp. ISBN 0-486-26629-X.

- Brown JH. 1973. Toxicology and Pharmacology of Venoms from Poisonous Snakes. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas. 184 pp. LCCCN 73-229. ISBN 0-398-02808-7.

- "Slangen van Suriname - Snakes of South America ( Suriname )". www.suriname123.com.

- Laurence Monroe Klauber (1997). Rattlesnakes: Their Habits, Life Histories, and Influence on Mankind (Second ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21056-1.

- "LD50 and venom yields | snakedatabase.org". snakedatabase.org. Retrieved 2020-03-12.

Further reading

- Alvaro ME. 1939. Snake Venom in Ophthalmology. Am. Jour. Opth., Vol. 22, No. 10, pp. 1130–1145.

- Wüster W, Ferguson JE, Quijada-Mascareñas JA, Pook CE, Salomão MG, Thorpe RS. 2005. Tracing an invasion: landbridges, refugia and the phylogeography of the Neotropical rattlesnake (Serpentes: Viperidae: Crotalus durissus). Molecular Ecology 14: 1095-1108. PDF at Wolfgang Wüster. Accessed 28 August 2007.

- Wüster W, Ferguson JE, Quijada-Mascareñas JA, Pook CE, Salomão MG, Thorpe RS. 2005. No rattlesnakes in the rainforests: reply to Gosling and Bush. Molecular Ecology, 14: 3619-3621. PDF at Wolfgang Wüster. Accessed 28 August 2007.

- Quijada-Mascareñas A, JE Ferguson, CE Pook, MG Salomão, RS Thorpe, & W Wüster. 2007. Phylogeographic patterns of Trans-Amazonian vicariants and Amazonian biogeography: The Neotropical rattlesnake (Crotalus durissus complex) as an example. Journal of Biogeography 34: 1296–1312. PDF

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crotalus durissus. |

- Crotalus durissus at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 19 August 2007.