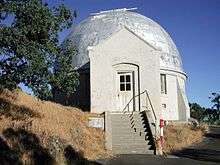

Crossley telescope

The Crossley telescope is a 36-inch (910 mm) reflecting telescope located at Lick Observatory in the U.S. state of California. It was used between 1895 to 2010, and was donated to the observatory by Edward Crossley, its namesake.

Mosaic image of the Crossley telescope. | |

| Named after | Edward Crossley |

|---|---|

| Part of | Lick Observatory |

| Location(s) | California |

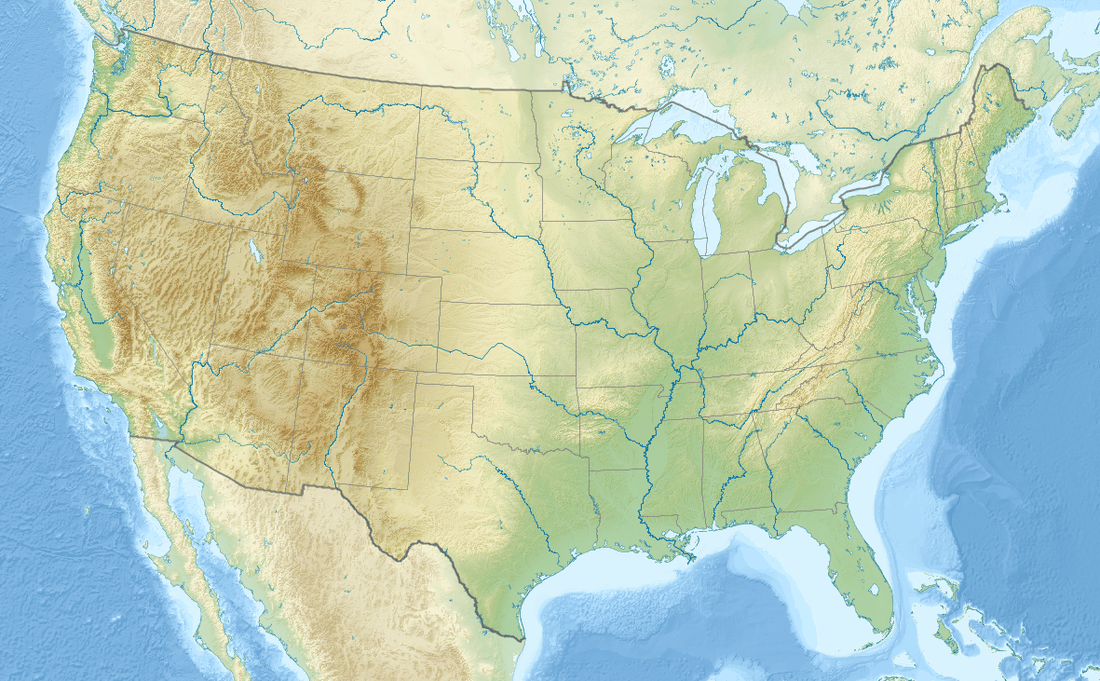

| Coordinates | 37°20′18″N 121°38′38″W |

| Discovered | Mayall's Object |

| Telescope style | optical telescope reflecting telescope |

| Diameter | 36 in (0.91 m) |

Location of Crossley telescope | |

_(14781868071).jpg)

It was the largest reflecting telescope in the United State for several years after its recommissioning in California.[1] Lick Director, Keeler, J. E. remarked of the Crossley in 1900, "... by far the most effective instrument in the Observatory for certain class of astronomical work."[1]

History

Given to the observatory in 1895 by British politician Edward Crossley, it was rebuilt from the ground up as it was on a very flimsy mounting. It was last used in 2010 in the search for extra-solar planets but has been taken out of service due to budget cuts. The mirror, and some of the initial mounts, came from the 36-inch reflector originally mounted in Andrew Ainslie Common's backyard Ealing observatory. He had used it from 1879 to 1886 to prove the concept of long exposure astrophotography (recording objects too faint to be seen by the naked eye for the first time). Common sold it to Crossley who had it until 1895.

The 36-inch A.A.Common mirror was made by George Calver for Common, and was ordered after Common wanted one bigger than the 18-inch reflecting telescope, which also had a mirror from Calver.[2] Common completed this telescope by 1879, and went on to make a 60-inch telescope; he sold the 36-inch to Crossley.[1] Crossley set the telescope up in Halifax, England in a new dome.[1]

Meanwhile, at the Lick observatory in America, the director learned that Crossley wanted to sell the well regarded Common 36-inch telescope.[3] Crossley exchanged letters with the director of the Mount Wilson Observatory, Holden, and worked out transferring the telescope to America.[4] Crossley was very impressed by the enhanced observing conditions at Mount Hamilton, and, in April 1895, he formally telegraphed the Lick that he would donate the telescope.[3]

Some additional funds had to be raised to ship the telescope to California, which included money from various donors, as well as donated services.[3] For example, the heavy parts of the telescope were shipped by The Southern Pacific Company at no cost, a service of over $1,000 USD (at that time).[3] Converting the buying power of 1896 dollars to 2017 dollars, that can be estimated at approximately $12,000 USD.[5]

The reflecting telescope type was scarcely used in the United States at the time of the donation, with a noted exception being the work of H. Draper's reflector.[6]

The astronomer James Edward Keeler became director of Mount Wilson Observatory, and undertook a series of modifications of the Crossley and explored its use in astrophotography.[4]

Observations by Keeler helped establish large reflecting telescopes with metal-coated glass mirrors as astronomically useful, as opposed to earlier cast speculum metal mirrors. Great refractors were still in vogue, but the Crossley reflector foreshadowed the success of large reflectors in the 1900s. Other large reflectors followed, such as the Harvard 60-inch Reflector (152 cm), also with a mirror by A.A. Common, or the 1 Meter Spiegelteleskop (39.4 inch reflector) of the Hamburg Observatory.[7] At this time the 72-inch Leviathan of Parsonstown was the largest by aperture, but it used a metal mirror. Despite the accomplishments of reflectors under Herschel, in the 19th century much of the astronomical community used relatively small refractors, often just a few inches in aperture, save for a few larger ones.

After Keeler died in 1900, the telescope was further reconstructed, quite significantly so, and was used to take several hundred photos of the Near-Earth asteroid 433 Eros.[4]

In the 1930s, the mirror was tested with vapor-deposited aluminum for reflection, rather than coated by using a silver metal precipitated out of a solution.[8] The telescope was aluminized in 1934, 1938, 1946, and 1951.[9]

Nicholas Mayall was a long time user of the Crossley and added a slitless spectrograph to extend its usefulness in the face of larger telescopes.

Discoveries & Observations

Mayall's Object was discovered by American astronomer Nicholas U. Mayall of the Lick Observatory on 13 March 1940, using the Crossley reflector.[10]

NGC 185 was first photographed between 1898 and 1900 by James Edward Keeler with the Crossley reflector.[11]

Other early photographic imaging targets, dating to 1899, include GC 4628 and GC 4964, GC 4373, and the "Ring nebula in Lyra." [6] Keeler notes that in a 4 hour exposure, 16 new nebulae were found, seeing objects that were normally much to hard to make out with the reflector visually.[6]

As an example of its performance, Keeler noted that in a two-hour exposure of the "cluster in Hercules" made on July 13, 1899, he could count 5400 stars on the photograph.[12] Keeler noted how with long exposure on this telescope the "swarms of minute stars" that gave it a nebulous look were resolved.[12]

In 1990, the Crossley was used to test the photometric detection of exoplanets, including around the star CM Draconis.[13]

Comets known to have been photographed using the Crossley include:[14]

- 1931 I (1931d) was found on plates taken in January 1931.

- 1941 IV (1941c) was observed visually and photographed in July 1941, after the comet re-emerged from around the Sun.

- 1946 III (1946b) was observed visually in July 1946.

- 1946 IV (1946e) was recorded on plates taken in June and July 1946.

In 1978, the Crossley was used to observe planetary nebulae with photoelectric photometry (spectrophotometry).[15]

Contemporaries on debut

Legend

- Reflector (Metal mirror) or unknown

- Glass Reflector (Silver on glass mirror)

- Refractor (Lens)

(100 cm equals 1 meter)

| Name/Observatory | Aperture cm (in) |

Type | Location | Extant* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leviathan of Parsonstown | 183 cm (72″) | reflector – metal | Birr Castle; Ireland | 1845–1908* |

| National Observatory, Paris | 120 cm (48″) | reflector – glass | Paris, France | 1875–1943[16] |

| Yerkes Observatory[17] | 102 cm (40″) | achromat | Williams Bay, Wisconsin, USA | 1897 |

| Meudon Observatory 1m[18] | 100 cm (39.4″) | reflector-glass | Meudon Observatory/ Paris Observatory | 1891 [19] |

| James Lick telescope, Lick Observatory | 91 cm (36″) | achromat | Mount Hamilton, California, USA | 1888 |

| Crossley Reflector[20] Lick Observatory | 91.4 cm(36″) | reflector – glass | Mount Hamilton, California, USA | 1896 |

| A.A. Common Reflector | 91.4 cm(36″) | reflector – glass | Great Britain | 1880–1896 |

| Rosse 36-inch Telescope | 91.4 cm(36″) | reflector – metal | Birr Castle; Ireland | 1826 |

| Grande Lunette, Paris Observatory | 83 cm + 62 cm (32.67" + 24.40") | achromat x2 | Meudon, France | 1891 |

*Note the Leviathan of Parsonstown was not used after 1890

See also

References

- Keeler, James E. (1900). "1900ApJ....11..325K Page 325". The Astrophysical Journal. 11: 325. Bibcode:1900ApJ....11..325K. doi:10.1086/140704.

- King, Henry C. (2003-01-01). The History of the Telescope. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486432656.

- California (1897). Appendix to the Journals of the Senate and Assembly ... of the Legislature of the State of California ... Sup't State Printing.

- "National Park Service: Astronomy and Astrophysics (Lick Crossley 36-inch Reflector)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- "1896 dollars in 2017 | Inflation Calculator". www.in2013dollars.com. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- Keeler, J. E. (1899). "1899Obs....22..437K Page 437". The Observatory. 22: 437. Bibcode:1899Obs....22..437K.

- A Short History of Hamburg Observatory, by Stuart R. Anderson and Dieter Engels Archived 2012-02-13 at the Wayback Machine, July 2004

- Wright, W. H. (February 1934). "The Optical Performance of the New Aluminized Mirror of the Crossley Telescope". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 46: 32. doi:10.1086/124395. ISSN 1538-3873.

- Stebbins, Joel; Smith, J. Lynn (1951). "1951PASP...63..202S Page 202". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 63 (373): 202. Bibcode:1951PASP...63..202S. doi:10.1086/126368.

- Smith, R. T. ; The Radial Velocity of a Peculiar Nebula ; Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Vol. 53, No. 313, p.187 Bibcode: 1941PASP...53..187S

- "SEDS — NGC 185".

- "1899Obs....22..437K Page 437". Bibcode:1899Obs....22..437K. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Doyle, L. R.; Dunham, E. T.; Deeg, H. J.; Blue, J. E.; Jenkins, J. M. (1996-06-25). "Ground-based detectability of terrestrial and Jovian extrasolar planets: observations of CM Draconis at Lick Observatory". Journal of Geophysical Research. 101 (E6): 14823–14829. doi:10.1029/96je00825. ISSN 0148-0227. PMID 11539351.

- NASA Technical Translation. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 1964.

- Barker, T. (1978). "1978ApJ...219..914B Page 914". The Astrophysical Journal. 219: 914. Bibcode:1978ApJ...219..914B. doi:10.1086/155854.

- "1914Obs....37..245H Page 250". Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2019-10-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Popular Astronomy". 1911.

- "Mt. Hamilton Telescopes: CrossleyTelescope". www.ucolick.org. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crossley telescope. |

- ucolick.org - Telescopes of the Lick Observatory - The 36 inch Crossley Reflector

- Astronomy and Astrophysics - Lick Crossley 36-inch Reflector

- Photographs of the Crossley Telescope used in the Lick Observatory from the Lick Observatory Records Digital Archive, UC Santa Cruz Library’s Digital Collections

- THE OPTICAL PERFORMANCE OF THE NEW ALUMINIZED MIRROR OF THE CROSSLEY TELESCOPE (year - 1934)