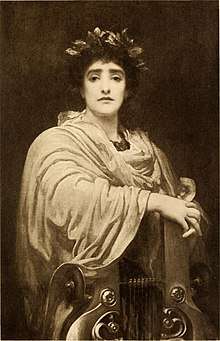

Corinna

Corinna or Korinna (Ancient Greek: Κορίννα, romanized: Korinna) was an ancient Greek lyric poet from Tanagra in Boeotia, described by Herbert Weir Smyth as the most famous ancient Greek woman poet after Sappho.[1] Although ancient testimonia portray her as a contemporary of Pindar (who lived between about 522 and 443 BC), not all modern scholars accept the accuracy of this tradition, and some claim that she is more likely to have lived in the Hellenistic period of 323 to 31 BC. Her works, which survive only in fragments, focus on local Boeotian legends. Her poetry is of interest as the work of one of the few preserved female poets from ancient Greece.

Life

%22_%22WILLIAM_BRODIE%22_from_-Sculptures_of_Andromeda%2C_the_Toilet_of_Atalanta%2C_Corinna%2C_and_a_Naiad-_MET_DP323119_(cropped).jpg)

Corinna was from Tanagra[lower-alpha 1] in Boeotia,[5] the daughter – according to the Suda – of Acheloodorus and Procratia.[2] According to ancient tradition, she lived during the 5th century BC.[6] She was supposed to have been a contemporary of Pindar, either having taught him, or been a fellow-pupil of Myrtis of Anthedon with Pindar.[lower-alpha 2][8] Corinna was said to have competed with Pindar, defeating him in at least one competition, though some sources claim five.[lower-alpha 3][8]

Since the early twentieth century, scholars have been divided over the accuracy of the traditional chronology of Corinna's life.[9] As early as 1930, Edgar Lobel argued that the language used in Corinna's surviving poetry seems to favour a later date than tradition suggests,[10] and that there is no reason to believe that Corinna significantly predated the mid-fourth century BC, the point at which the orthography preserved in the Berlin Papyrus of Corinna's poetry began to be used.[11] More recently, M. L. West has argued for dating Corinna to the late third century BC, and W. J. Henderson supports a middle-ground, between West's very late and the traditional early date.[9] David A. Campbell judges it "almost certain" that her poetry belongs to the 3rd century BC.[12] Other scholars, such as Archibald Allen and Jiri Frel, argue for the accuracy of the traditional date,[13] writing that a Hellenistic Corinna as argued for by West would be "astonishing".[14] An apparent terminus ante quem is established by the report in Tatian's Oration against the Greeks of a sculpture of Corinna by Silanion (fl. c.325 BC), though Tatian's report has been doubted.[15] The evidence remains inconclusive.[16] According to Suda, she was nicknamed Muia (Μυῖα), meaning 'fly' (the insect).[17]

Poetry

Corinna, like Pindar, wrote choral lyric poetry – as demonstrated by her invocation of Terpsichore, the Muse of dance and chorus, in one of her fragments.[18] According to the Suda, she wrote five books of poetry.[12] She wrote in the Boeotian dialect,[19] though her language also has similarities to the language of epic both in morphology and in her choice of words.[20] If Corinna was a contemporary of Pindar, this use of the local vernacular as a literary language is archaic – paralleled in the works of Alcman and Stesichoros, while Pindar and Bacchylides both wrote in the Doric dialect. On the other hand, if she is to be located closer to the Hellenistic period, parallels can be found in the poetry of Theocritus.[21]

Forty-two fragments of Corinna's poetry survive, though no complete poems of hers are known.[22] The three most substantial fragments are preserved on pieces of papyrus discovered in Hermopolis and Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, dating to the second century AD;[lower-alpha 4] many of the shorter fragments survive in citations by grammarians interested in Corinna's Boeotian dialect.[22]

Corinna's language is clear, simple, and generally undecorated,[24] and she tends to use simple metrical schemes.[25] Her poetry focuses more on the narrative than on intricate use of language,[26] and her tone is often ironic or humorous, in contrast with the serious tone of Pindar.[27]

Corinna's poetry often reworks mythological tradition:[28] Derek Collins writes that "the most distinctive feature of Corinna's poetry is her mythological innovation".[29] One ancient story says that Corinna considered that myth was the proper subject for poetry, rebuking Pindar for not paying sufficient attention to it.[lower-alpha 5][30] According to this story, Pindar responded to this criticism by packing his next ode full of myths, leading Corinna to advise him, "Sow with the hand, not with the sack."[1] Corinna's poetry concentrates on local legends,[31] with poems about Orion, Oedipus, and the Seven Against Thebes.[32] Her Orestes[lower-alpha 6] is possibly an exception to her focus on Boeotian legends.[12]

Two of Corinna's most substantial fragments, the "Daughters of Asopus" and "Terpsichore" poems, demonstrate a strong interest in genealogy.[33] This genealogical focus is reminiscent of the works of Hesiod, especially the Catalogue of Women, though other lost genealogical poetry is known from the archaic period – for instance by Asius of Samos and Eumelus of Corinth.[34] The third major surviving fragment of Corinna's poetry, on the contest between Mount Cithaeron and Mount Helicon, seems also to have been influenced by Hesiod, who also wrote an account of this myth.[35]

Marylin Skinner argues that Corinna's poetry is part of the tradition of "women's poetry" in ancient Greece, though it differs significantly from Sappho's conception of that genre.[36] She considers that although it was written by a woman, Corinna's poetry tells stories from a patriarchal point of view,[36] describing women's lives from a masculine perspective.[37]

Performance context

The circumstances in which Corinna's poetry was performed are uncertain, and have been the subject of much scholarly debate. At least some of her poetry was probably performed for a mixed-gender audience, though some may have been intended for a specifically female audience.[38] Marylin Skinner suggests that Corinna's songs were composed for performance by a chorus of young girls in religious festivals, and were related to the ancient genre of partheneia.[18] The poems may have been performed at cult celebrations in the places which appear in her poetry. Particular settings suggested include the Mouseia at Thespia, proposed by West, and at the festival of the Daedala at Plataea, suggested by Gabriele Burzacchini.[39]

Reception

Corinna seems to have been well-regarded by the people of ancient Tanagra, her hometown. Pausanias reports that there was a monument to her in the streets of the town – probably a statue – and a painting of her in the gymnasium.[40] Tatian writes in his Oratio ad Graecos that Silanion had sculpted her.[lower-alpha 7][15] In the early Roman Empire, Corinna's poetry was popular:[5] the earliest mention of Corinna is by the first century BC poet Antipater of Thessalonica, who includes her in his selection of nine "mortal muses".[41] Alexander Polyhistor wrote a commentary on her work.[42]

However, modern critics have tended to dismiss Corinna's work, considering it dull.[43] Athanassios Vergados argues that Corinna's poor reception among modern critics is due to her concern with local Boeotian legend, which gave her the reputation of being provincial and therefore second-rate.[15] Though her poetry is not well-regarded by critics, Corinna's work has been of interest to feminist literary historians, as one of the few extant examples of ancient Greek women's poetry.[5]

Notes

- The Suda says that she came from Tanagra or Thebes;[2] Pausanias says Tanagra.[3] Most scholars accept Tanagra as Corinna's home.[4]

- The vita metrica claims Corinna taught Pindar;[7] the Suda that she studied under Myrtis[2]

- Pausanias says once; Suda and Aelian five times.

- PMG 654, which contains the "Contest of Helicon and Cithaeron" and "Daughters of Asopus" fragments comes from P.Berol. 284; PMG 655, the "Terpsichore" fragment, comes from P.Oxy. 2370.[23]

- The story is told in Plutarch's On the Glory of the Athenians.

- fragment 690 in Denys Page's Poetae Melici Graeci

- As Silanion was active in the fourth century BC, this report is problematic for those scholars who believe that Corinna dates to the third century, and the existence of the statue Tatian reports has been doubted; Athanassios Vergados describes such doubts as unjustifiable.[15]

References

- Smyth 1963, p. 337

- Suda κ 2087, "Corinna"

- Pausanias 9.22.3

- Berman 2010, p. 41

- Skinner 1983, p. 9

- West 1990, p. 553

- vita metrica 9 f.

- Allen & Frel 1972, p. 26

- Collins 2006, p. 19

- Lobel 1930, p. 364

- Lobel 1930, pp. 356, 365

- Campbell 1992, pp. 1–3

- Collins 2006, p. 19, n. 6

- Allen & Frel 1972, p. 28

- Vergados 2017, p. 244

- Vergados 2017, pp. 243-4

- ka.2087

- Skinner 1983, p. 11

- Berman 2010, p. 53

- Berman 2010, pp. 54-5

- Berman 2010, p. 56

- Plant 2004, p. 92

- Plant 2004, p. 222

- Campbell 1967, p. 410

- Skinner 1983, p. 9

- Larmour 2005, p. 46

- Larmour 2005, p. 47

- Larmour 2005, p. 29

- Collins 2006, p. 21

- Collins 2006, p. 26

- West 1990, p. 555

- Snyder 1991, pp. 44–5

- Larson 2002, p. 50.

- Larson 2002, p. 49.

- Collins 2006, pp. 26–8.

- Skinner 1983, p. 10

- Skinner 1983, p. 15

- Larmour 2005, p. 25

- Larmour 2005, p. 37

- Snyder 1991, p. 42

- Snyder 1991, p. 43.

- Vergados 2017, p. 245

- Skinner 1983, p. 17

Works cited

- Allen, Archibald; Frel, Jiri (1972). "A Date for Corinna". The Classical Journal. 68 (1).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Berman, Daniel W. (2010). "The Language and Landscape of Korinna". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 50.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, D. A. (1967). Greek Lyric Poetry: a Selection. New York: Macmillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, D. A. (1992). Greek Lyric Poetry IV: Bacchylides, Corrina, and Others. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Derek (2006). "Corinna and Mythological Innovation". The Classical Quarterly. 56 (1).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Larmour, David H.J. (2005). "Corinna's Poetic Metis and the Epinikian Tradition". In Greene, Ellen (ed.). Women Poets in Ancient Greece and Rome. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Larson, Jennifer (2002). "Corinna and the Daughters of Asopus". Syllecta Classica. 13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lobel, Edgar (1930). "Corinna". Hermes. 65 (3).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Plant, I. M. (2004). Women Writers of Ancient Greece and Rome: an Anthology. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skinner, Marylin B. (1983). "Corinna of Tanagra and her Audience". Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature. 2 (1).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1963). Greek Melic Poets (4th ed.). New York: Biblo and Tannen.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Snyder, Jane McIntosh (1991). The Woman and the Lyre: Women Writers in Classical Greece and Rome. Carbondale: SIU Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vergados, Athanassios (2017). "Corinna". In Sider, David (ed.). Hellenistic Poetry: A Selection. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- West, Martin L. (1990). "Dating Corinna". The Classical Quarterly. 40 (2).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Corinna |