Conversion between quaternions and Euler angles

Spatial rotations in three dimensions can be parametrized using both Euler angles and unit quaternions. This article explains how to convert between the two representations. Actually this simple use of "quaternions" was first presented by Euler some seventy years earlier than Hamilton to solve the problem of magic squares. For this reason the dynamics community commonly refers to quaternions in this application as "Euler parameters".

Definition

For the rest of this article, the JPL quaternion convention[1] shall be used. A unit quaternion can be described as:

We can associate a quaternion with a rotation around an axis by the following expression

where α is a simple rotation angle (the value in radians of the angle of rotation) and cos(βx), cos(βy) and cos(βz) are the "direction cosines" locating the axis of rotation (Euler's Rotation Theorem).

Tait–Bryan angles

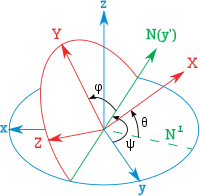

Similarly for Euler angles, we use the Tait Bryan angles (in terms of flight dynamics):

- Bank – : rotation about the new X-axis

- Attitude – : rotation about the new Y-axis

- Heading – : rotation about the Z-axis

where the X-axis points forward, Y-axis to the right and Z-axis downward with angles defined for clockwise/lefthand rotation. In the conversion example above the rotation occurs in the order heading, attitude, bank (about intrinsic axes).

Rotation matrices

The orthogonal matrix (post-multiplying a column vector) corresponding to a clockwise/left-handed (looking along positive axis to origin) rotation by the unit quaternion is given by the inhomogeneous expression:

or equivalently, by the homogeneous expression:

If is not a unit quaternion then the homogeneous form is still a scalar multiple of a rotation matrix, while the inhomogeneous form is in general no longer an orthogonal matrix. This is why in numerical work the homogeneous form is to be preferred if distortion is to be avoided.

The direction cosine matrix (from the rotated Body XYZ coordinates to the original Lab xyz coordinates for a clockwise/lefthand rotation) corresponding to a post-multiply Body 3-2-1 sequence with Euler angles (ψ, θ, φ) is given by:[2]

Euler Angles to Quaternion Conversion

By combining the quaternion representations of the Euler rotations we get for the Body 3-2-1 sequence, where the airplane first does yaw (Body-Z) turn during taxiing onto the runway, then pitches (Body-Y) during take-off, and finally rolls (Body-X) in the air. The resulting orientation of Body 3-2-1 sequence (around the capitalized axis in the illustration of Tait–Bryan angles) is equivalent to that of lab 1-2-3 sequence (around the lower-cased axis), where the airplane is rolled first (lab-x axis), and then nosed up around the horizontal lab-y axis, and finally rotated around the vertical lab-z axis (lB = lab2Body):

Other rotation sequences use different conventions.[2]

Source Code

Below code in C++ illustrates above conversion:

struct Quaternion

{

double w, x, y, z;

};

Quaternion ToQuaternion(double yaw, double pitch, double roll) // yaw (Z), pitch (Y), roll (X)

{

// Abbreviations for the various angular functions

double cy = cos(yaw * 0.5);

double sy = sin(yaw * 0.5);

double cp = cos(pitch * 0.5);

double sp = sin(pitch * 0.5);

double cr = cos(roll * 0.5);

double sr = sin(roll * 0.5);

Quaternion q;

q.w = cr * cp * cy + sr * sp * sy;

q.x = sr * cp * cy - cr * sp * sy;

q.y = cr * sp * cy + sr * cp * sy;

q.z = cr * cp * sy - sr * sp * cy;

return q;

}

Quaternion to Euler Angles Conversion

The Euler angles can be obtained from the quaternions via the relations:[3]

Note, however, that the arctan and arcsin functions implemented in computer languages only produce results between −π/2 and π/2, and for three rotations between −π/2 and π/2 one does not obtain all possible orientations. To generate all the orientations one needs to replace the arctan functions in computer code by atan2:

Source Code

The following C++ program illustrates conversion above:

#define _USE_MATH_DEFINES

#include <cmath>

struct Quaternion {

double w, x, y, z;

};

struct EulerAngles {

double roll, pitch, yaw;

};

EulerAngles ToEulerAngles(Quaternion q) {

EulerAngles angles;

// roll (x-axis rotation)

double sinr_cosp = 2 * (q.w * q.x + q.y * q.z);

double cosr_cosp = 1 - 2 * (q.x * q.x + q.y * q.y);

angles.roll = std::atan2(sinr_cosp, cosr_cosp);

// pitch (y-axis rotation)

double sinp = 2 * (q.w * q.y - q.z * q.x);

if (std::abs(sinp) >= 1)

angles.pitch = std::copysign(M_PI / 2, sinp); // use 90 degrees if out of range

else

angles.pitch = std::asin(sinp);

// yaw (z-axis rotation)

double siny_cosp = 2 * (q.w * q.z + q.x * q.y);

double cosy_cosp = 1 - 2 * (q.y * q.y + q.z * q.z);

angles.yaw = std::atan2(siny_cosp, cosy_cosp);

return angles;

}

Singularities

One must be aware of singularities in the Euler angle parametrization when the pitch approaches ±90° (north/south pole). These cases must be handled specially. The common name for this situation is gimbal lock.

Code to handle the singularities is derived on this site: www.euclideanspace.com

Vector Rotation

Let us define scalar and vector such that .

Note that the canonical way to rotate a three-dimensional vector by a quaternion defining an Euler rotation is via the formula

where is a quaternion containing the embedded vector , is a conjugate quaternion, and is the rotated vector . In computational implementations this requires two quaternion multiplications. An alternative approach is to apply the pair of relations

where indicates a three-dimensional vector cross product. This involves fewer multiplications and is therefore computationally faster. Numerical tests indicate this latter approach may be up to 30% [4] faster than the original for vector rotation.

Proof

The general rule for quaternion multiplication involving scalar and vector parts is given by

Using this relation one finds for that

and upon substitution for the triple product

where anti-commutivity of cross product and has been applied. By next exploiting the property that is a unit quaternion so that , along with the standard vector identity

one obtains

which upon defining can be written in terms of scalar and vector parts as

See also

- Rotation operator (vector space)

- Quaternions and spatial rotation

- Euler Angles

- Rotation matrix

- Rotation formalisms in three dimensions

References

- W. G. Breckenridge, "Quaternions proposed standard conventions," NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Technical Report, Oct. 1979.

- NASA Mission Planning and Analysis Division. "Euler Angles, Quaternions, and Transformation Matrices" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- Blanco, Jose-Luis (2010). "A tutorial on se (3) transformation parameterizations and on-manifold optimization". University of Malaga, Tech. Rep. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.468.5407.

- Janota, A; Šimák, V; Nemec, D; Hrbček, J (2015). "Improving the Precision and Speed of Euler Angles Computation from Low-Cost Rotation Sensor Data". Sensors. 15 (3): 7016–7039. doi:10.3390/s150307016. PMC 4435132. PMID 25806874.

External links

- Q60. How do I convert Euler rotation angles to a quaternion? and related questions at The Matrix and Quaternions FAQ