Consumer electronics

Consumer electronics or home electronics are electronic (analog or digital) equipment intended for everyday use, typically in private homes. Consumer electronics include devices used for entertainment (flatscreen TVs, DVD players, video games, remote control cars, etc.), communications (telephones, cell phones, e-mail-capable laptops, etc.), and home-office activities (e.g., desktop computers, printers, paper shredders, etc.). In British English, they are often called brown goods by producers and sellers, to distinguish them from "white goods" which are meant for housekeeping tasks, such as washing machines and refrigerators, although nowadays, these would be considered brown goods, some of these being connected to the Internet.[1][n 1] In the 2010s, this distinction is not always present in large big box consumer electronics stores, which sell both entertainment, communication, and home office devices and kitchen appliances such as refrigerators.

Radio broadcasting in the early 20th century brought the first major consumer product, the broadcast receiver. Later products included telephones, televisions and calculators, then audio and video recorders and players, game consoles, personal computers and MP3 players. In the 2010s, consumer electronics stores often sell GPS, automotive electronics (car stereos), video game consoles, electronic musical instruments (e.g., synthesizer keyboards), karaoke machines, digital cameras, and video players (VCRs in the 1980s and 1990s, followed by DVD players and Blu-ray players). Stores also sell smart appliances, digital cameras, camcorders, cell phones, and smartphones. Some of the newer products sold include virtual reality head-mounted display goggles, smart home devices that connect home devices to the Internet and wearable technology.

In the 2010s, most consumer electronics have become based on digital technologies, and have largely merged with the computer industry in what is increasingly referred to as the consumerization of information technology. Some consumer electronics stores, have also begun selling office and baby furniture. Consumer electronics stores may be "brick and mortar" physical retail stores, online stores, or combinations of both.

Annual consumer electronics sales are expected to reach $2.9 trillion by 2020.[3] It is part of the wider electronics industry. In turn, the driving force behind the electronics industry is the semiconductor industry.[4] The basic building block of modern electronics is the MOSFET (metal-oxide-silicon field-effect transistor, or MOS transistor),[5][6] the scaling and miniaturization of which has been the primary factor behind the rapid exponential growth of electronic technology since the 1960s.[7]

History

For its first fifty years the phonograph turntable did not use electronics; the needle and soundhorn were purely mechanical technologies. However, in the 1920s radio broadcasting became the basis of mass production of radio receivers. The vacuum tubes that had made radios practical were used with record players as well, to amplify the sound so that it could be played through a loudspeaker. Television was soon invented, but remained insignificant in the consumer market until the 1950s.

The first working transistor, a point-contact transistor, was invented by John Bardeen and Walter Houser Brattain at Bell Laboratories in 1947, which led to significant research in the field of solid-state semiconductors in the early 1950s.[8] The invention and development of the earliest transistors at Bell led to transistor radios. This led to the emergence of the home entertainment consumer electronics industry starting in the 1950s, largely due to the efforts of Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo (now Sony) in successfully commercializing transistor technology for a mass market, with affordable transistor radios and then transistorized television sets.[9]

Mohamed M. Atalla's surface passivation process, developed at Bell in 1957, led to the planar process and planar transistor developed by Jean Hoerni at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1959,[10] from which comes the origins of Moore's law,[11] and the invention of the MOSFET (metal–oxide–silicon field-effect transistor, or MOS transistor) by Mohamed Atalla and Dawon Kahng at Bell in 1959.[5][6][12] The MOSFET was the first truly compact transistor that could be miniaturised and mass-produced for a wide range of uses,[13] enabling Moore's law[14] and revolutionizing the electronics industry.[15][16] It has since been the building block of modern digital electronics,[12][17] and the "workhorse" of the electronics industry.[18]

Integrated circuits (ICs) followed when manufacturers built circuits (usually for military purposes) on a single substrate using electrical connections between circuits within the chip itself. The most common type of IC is the MOS integrated circuit chip, capable of the large-scale integration (LSI) of MOSFETs on an IC chip. MOS technology led to more advanced and cheaper consumer electronics, such as transistorized televisions, pocket calculators, and by the 1980s, affordable video game consoles and personal computers that regular middle-class families could buy. The rapid progress of the electronics industry during the late 20th to early 21st centuries was achieved by rapid MOSFET scaling (related to Dennard scaling and Moore's law), down to sub-micron levels and then nanoelectronics in the early 21st century.[19] The MOSFET is the most widely manufactured device in history, with an estimated total of 13 sextillion MOSFETs manufactured between 1960 and 2018.[20][21]

Products

Main consumer electronics products include radio receivers, television sets, MP3 players, video recorders, DVD players, digital cameras, camcorders, personal computers, video game consoles, telephones and mobile phones.[22] Increasingly these products have become based on digital technologies, and have largely merged with the computer industry in what is increasingly referred to as the consumerization of information technology such as those invented by Apple Inc. and MIT Media Lab.

Trends

One overriding characteristic of consumer electronic products is the trend of ever-falling prices. This is driven by gains in manufacturing efficiency and automation, lower labor costs as manufacturing has moved to lower-wage countries, and improvements in semiconductor design.[23] Semiconductor components benefit from Moore's law, an observed principle which states that, for a given price, semiconductor functionality doubles every two years.

While consumer electronics continues in its trend of convergence, combining elements of many products, consumers face different decisions when purchasing. There is an ever-increasing need to keep product information updated and comparable, for the consumer to make an informed choice. Style, price, specification, and performance are all relevant. There is a gradual shift towards e-commerce web-storefronts.

Many products include Internet connectivity using technologies such as Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, EDGE or Ethernet. Products not traditionally associated with computer use (such as TVs or Hi-Fi equipment) now provide options to connect to the Internet or to a computer using a home network to provide access to digital content. The desire for high-definition (HD) content has led the industry to develop a number of technologies, such as WirelessHD or ITU-T G.hn, which are optimized for distribution of HD content between consumer electronic devices in a home.

Manufacturing

Most consumer electronics are built in China, due to maintenance cost, availability of materials, quality, and speed as opposed to other countries such as the United States.[24] Cities such as Shenzhen have become important production centres for the industry, attracting many consumer electronics companies such as Apple Inc.[25]

Electronic component

An electronic component is any basic discrete device or physical entity in an electronic system used to affect electrons or their associated fields. Electronic components are mostly industrial products, available in a singular form and are not to be confused with electrical elements, which are conceptual abstractions representing idealized electronic components.

Software development

Consumer electronics such as personal computers use various types of software. Embedded software is used within some consumer electronics, such as mobile phones.[26] This type of software may be embedded within the hardware of electronic devices.[27] Some consumer electronics include software that is used on a personal computer in conjunction with electronic devices, such as camcorders and digital cameras, and third-party software for such devices also exists.

Standardization

Some consumer electronics adhere to protocols, such as connection protocols "to high speed bi-directional signals".[28] In telecommunications, a communications protocol is a system of digital rules for data exchange within or between computers.

Trade shows

The Consumer Electronics Show (CES) trade show has taken place yearly in Las Vegas, Nevada since its foundation in 1973. The event, which grew from having 100 exhibitors in its inaugural year to more than 4,500 exhibiting companies in its 2020 edition, features the latest in consumer electronics, speeches by industry experts and innovation awards.[29]

The Internationale Funkausstellung Berlin (IFA) trade show has taken place Berlin, Germany since its foundation in 1924. The event features new consumer electronics and speeches by industry pioneers.

IEEE initiatives

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), the world's largest professional society, has many initiatives to advance the state of the art of consumer electronics. IEEE has a dedicated society of thousands of professionals to promote CE, called the Consumer Electronics Society (CESoc).[30] IEEE has multiple periodicals and international conferences to promote CE and encourage collaborative research and development in CE. The flagship conference of CESoc, called IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), is on its 35th year.

Retailing

Electronics retailing is a significant part of the retail industry in many countries. In the United States, dedicated consumer electronics stores have mostly given way to big-box retailers such as Best Buy, the largest consumer electronics retailer in the country,[34] although smaller dedicated stores include Apple Stores, and specialist stores that serve, for example, audiophiles and exceptions, such as the single-branch B&H Photo store in New York City. Broad-based retailers, such as Wal-Mart and Target, also sell consumer electronics in many of their stores.[34] In April 2014, retail e-commerce sales were the highest in the consumer electronic and computer categories as well.[35] Some consumer electronics retailers offer extended warranties on products with programs such as SquareTrade.[36]

An electronics district is an area of commerce with a high density of retail stores that sell consumer electronics.[37]

Industries

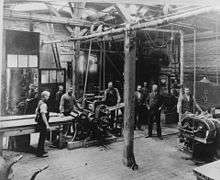

The electronics industry, especially meaning consumer electronics, emerged in the 20th century and has now become a global industry worth billions of dollars. Contemporary society uses all manner of electronic devices built in automated or semi-automated factories operated by the industry.

Mobile phone industry

By country

Service and repair

Consumer electronic service can refer to the maintenance of said products. When consumer electronics have malfunctions, they may sometimes be repaired.

In 2013 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the increased popularity in listening to sound from analog audio devices, such as record players, as opposed to digital sound, has sparked a noticeable increase of business for the electronic repair industry there.[38]

Environmental impact

Energy consumption

The energy consumption of consumer electronics and their environmental impact, either from their production processes or the disposal of the devices, is increasing steadily. EIA estimates that electronic devices and gadgets account for about 10%–15% of the energy use in American homes – largely because of their number; the average house has dozens of electronic devices.[39] The energy consumption of consumer electronics increases – in America and Europe – to about 50% of household consumption, if the term is redefined to include home appliances such as refrigerators, dryers, clothes washers and dishwashers.

Standby power

Standby power – used by consumer electronics and appliances while they are turned off – accounts for 5–10% of total household energy consumption, costing $100 annually to the average household in the United States.[40] A study by United States Department of Energy's Berkeley Lab found that a videocassette recorders (VCRs) consume more electricity during the course of a year in standby mode than when they are used to record or playback videos. Similar findings were obtained concerning satellite boxes, which consume almost the same amount of energy in "on" and "off" modes.[41]

A 2012 study in the United Kingdom, carried out by the Energy Saving Trust, found that the devices using the most power on standby mode included televisions, satellite boxes and other video and audio equipment. The study concluded that UK households could save up to £86 per year by switching devices off instead of using standby mode.[42] A report from the International Energy Agency in 2014 found that $80 billion of power is wasted globally per year due to inefficiency of electronic devices.[43] Consumers can reduce unwanted use of standby power by unplugging their devices, using power strips with switches, or by buying devices that are standardized for better energy management, particularly Energy Star marked products.[40]

Electronic waste

Electronic waste describes discarded electrical or electronic devices. Many consumer electronics may contain toxic minerals and elements,[44] and many electronic scrap components, such as CRTs, may contain contaminants such as lead, cadmium, beryllium, mercury, dioxins, or brominated flame retardants. Electronic waste recycling may involve significant risk to workers and communities and great care must be taken to avoid unsafe exposure in recycling operations and leaking of materials such as heavy metals from landfills and incinerator ashes. However, large amounts of the produced electronic waste from developed countries is exported, and handled by the informal sector in countries like India, despite the fact that exporting electronic waste to them is illegal. Strong informal sector can be a problem for the safe and clean recycling.[45]

Reuse and repair

E-waste policy has gone through various incarnations since the 1970s, with emphases changing as the decades passed. More weight was gradually placed on the need to dispose of e-waste more carefully due to the toxic materials it may contain. There has also been recognition that various valuable metals and plastics from waste electrical equipment can be recycled for other uses. More recently the desirability of reusing whole appliances has been foregrounded in the ‘preparation for reuse’ guidelines. The policy focus is slowly moving towards a potential shift in attitudes to reuse and repair.

With turnover of small household appliances high and costs relatively low, many consumers will throw unwanted electric goods in the normal dustbin, meaning that items of potentially high reuse or recycling value go to landfills. While larger items such as washing machines are usually collected, it has been estimated that the 160,000 tonnes of EEE in regular waste collections was worth £220 million. And 23% of EEE taken to Household Waste Recycling Centres was immediately resaleable – or would be with minor repairs or refurbishment. This indicates a lack of awareness among consumers as to where and how to dispose of EEE, and of the potential value of things that are literally going in the bin.

For reuse and repair of electrical goods to increase substantially in the UK there are barriers that must be overcome. These include people’s mistrust of used equipment in terms of whether it will be functional, safe, and the stigma for some of owning second-hand goods. But the benefits of reuse could allow lower income households access to previously unaffordable technology whilst helping the environment at the same time.<Cole, C., Cooper, T. and Gnanapragasam, A., 2016. Extending product lifetimes through WEEE reuse and repair: opportunities and challenges in the UK. In: Electronics Goes Green 2016+ Conference, Berlin, Germany, 7–9 September 2016>

Health impact

Desktop monitors and laptops produce major physical health concerns for humans when bodies are forced into positions that are unhealthy and uncomfortable in order to see the screen better. From this, neck and back pains and problems increase, commonly referred to as repetitive strain injuries. Using electronics before going to bed makes it difficult for people to fall asleep, which has a negative effect on human health. Sleeping less prevents people from performing to their full potential physically and mentally and can also “increase rates of obesity and diabetes,” which are “long-term health consequences”.[46] Obesity and diabetes are more commonly seen in students and in youth because they tend to be the ones using electronics the most. “People who frequently use their thumbs to type text messages on cell phones can develop a painful affliction called De Quervain syndrome that affects their tendons on their hands. The best known disease in this category is called carpal tunnel syndrome, which results from pressure on the median nerve in the wrist”.[46]

Notes

See also

References

- "brown goods". Collins English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- McDermott, Catherine (30 October 2007). Design: The Key Concepts. Routledge. p. 234. ISBN 9781134361809. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- "Global Consumer Electronics Market to Reach US$ 2.9 Trillion by 2020 - Persistence Market Research". PR Newswire. Persistence Market Research. 3 January 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- "Annual Semiconductor Sales Increase 21.6 Percent, Top $400 Billion for First Time". Semiconductor Industry Association. 5 February 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- "1960 - Metal Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) Transistor Demonstrated". The Silicon Engine. Computer History Museum.

- "Who Invented the Transistor?". Computer History Museum. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- Lamba, V.; Engles, D.; Malik, S. S.; Verma, M. (2009). "Quantum transport in silicon double-gate MOSFET". 2009 2nd International Workshop on Electron Devices and Semiconductor Technology: 1–4. doi:10.1109/EDST.2009.5166116.

- Manuel, Castells (1996). The information age : economy, society and culture. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631215943. OCLC 43092627.

- Hagiwara, Yoshiaki (2001). "Microelectronics for Home Entertainment". In Oklobdzija, Vojin G. (ed.). The Computer Engineering Handbook. CRC Press. p. 41-1. ISBN 978-0-8493-0885-7.

- Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 120. ISBN 9783540342588.

- Schaller, Bob (26 September 1996). "The Origin, Nature, and Implications of Moore's Law. The Benchmark of Progress in Semiconductor Electronics". Microsoft Research. Archived from the original on 28 August 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

Moore viewed the 1959 innovation of the planar transistor as the origin of "Moore's Law. [...] When we were patenting this [planar transistor] we recognized it was a significant change, and the patent attorney asked us if we really thought through all the ramifications of it. And we hadn't, so Noyce got a group together to see what they could come up with and right away he saw that this gave us a reason now you could run the metal up over the top without shorting out the junctions, so you could actually connect this one to the next-door neighbor or some other thing.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Triumph of the MOS Transistor". YouTube. Computer History Museum. 6 August 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- Moskowitz, Sanford L. (2016). Advanced Materials Innovation: Managing Global Technology in the 21st century. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 165–167. ISBN 9780470508923.

- "Transistors Keep Moore's Law Alive". EETimes. 12 December 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- Chan, Yi-Jen (1992). Studies of InAIAs/InGaAs and GaInP/GaAs heterostructure FET's for high speed applications. University of Michigan. p. 1.

The Si MOSFET has revolutionized the electronics industry and as a result impacts our daily lives in almost every conceivable way.

- Grant, Duncan Andrew; Gowar, John (1989). Power MOSFETS: theory and applications. Wiley. p. 1. ISBN 9780471828679.

The metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) is the most commonly used active device in the very large-scale integration of digital integrated circuits (VLSI). During the 1970s these components revolutionized electronic signal processing, control systems and computers.

- Raymer, Michael G. (2009). The Silicon Web: Physics for the Internet Age. CRC Press. p. 365. ISBN 9781439803127.

- Colinge, Jean-Pierre; Greer, James C. (2016). Nanowire Transistors: Physics of Devices and Materials in One Dimension. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9781107052406.

- Franco, Jacopo; Kaczer, Ben; Groeseneken, Guido (2013). Reliability of High Mobility SiGe Channel MOSFETs for Future CMOS Applications. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9789400776630.

- "13 Sextillion & Counting: The Long & Winding Road to the Most Frequently Manufactured Human Artifact in History". Computer History Museum. 2 April 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Baker, R. Jacob (2011). CMOS: Circuit Design, Layout, and Simulation. John Wiley & Sons. p. 7. ISBN 978-1118038239.

- "Consumer Electronics Manufacturing Industry Overview". Hoover's. Archived from the original on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- Mike Deng (23 October 2012). "China Moves to Automate Electronics Manufacturing". Quality Digest. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- Baker, Phil (11 August 2014). "Why can't the US build consumer electronic products?". San Diego Source. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- Gamble, Craig (22 August 2014). "Shenzhen in China becomes a power source for the electronics industry". Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 25 August 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- Hachman, Mark (4 September 2014). "Microsoft announces two Lumia phones, always-on Cortana, and clever new mobile accessories". PC World. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- "Electronics hardware consumption poised to touch *360 bln by 2015". One India. 13 April 2008. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- "Signal Converter of Consumer Electronics Connection Protocols (US 20120287942 A1)". IFI CLAIMS Patent Services. 15 November 2012. Archived from the original on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- Hornyak, Tim (2 September 2014). "Jack Wayman, founder of CES trade show, dies at 92". PC World. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- IEEE Consumer Electronics Society, http://cesoc.ieee.org/ Archived 31 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Simon Sherratt, Editor-in-Chief (EiC), IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics, http://cesoc.ieee.org/publications/ieee-transactions-on-consumer-electronics.html Archived 29 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Saraju P. Mohanty, Editor-in-Chief (EiC), IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine, http://cesoc.ieee.org/publications/ce-magazine.html Archived 12 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), http://www.icce.org/ Archived 23 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Murphy, H. Lee (27 January 2014). "Why consumer electronics retailers are the next record store". Crain's Chicago Business. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- eMarketer (11 April 2014). "US Retail Ecommerce Sales Highest for Computers, Consumer Electronics". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Sherman, Erik (19 December 2011). "Hold off extended warranties until you read this". CBS News (Moneywatch). Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Cellan-Jones, Rory (8 December 2012). "Look round Shenzhen's Electronics District". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- Todd, Deborah M. (18 August 2013). "Electronic repair industry gets second wind". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- "Heating and cooling no longer majority of US home energy use" Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. EIA.gov

- Chu, John (1 November 2012). "3 Easy Tips to Reduce Your Standby Power Loads". Energy.gov. United States Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- Lippert, John (17 August 2009). "Please Stand By: Reduce Your Standby Power Use". Energy.gov. United States Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- Harvey, Fiona (26 June 2012). "Leaving appliances on standby 'can cost UK households up to £86 a year'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- Carr, Matthew (2 July 2014). "Electronic Devices Waste $80 Billion of Power a Year, IEA Says". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- Moreno, Julia (8 September 2014). "Normal is recycling out-of-date electronics". Vidette Online. Illinois State University. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- Bhowmick, Nilanjana (23 May 2011). "Is India's E-Waste Problem Spiraling Out of Control?". Time. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- "Health Risks of Electronic Devices". The Women's International Perspective. 12 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 June 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

Further reading

- Kevin Sintumuang (2 January 2015). "Tech Etiquette: 21 Do's and Don'ts". The Wall Street Journal.