Conservative Party (Mexico)

The Conservative Party was a Mexican political party that sought to preserve the organization and colonial Spanish values, both in government and in society. Although as a party it was founded in 1849, after the defeat of Mexico in the war with the United States, most of the political ideology directly descended from the Jesuits expelled in the 18th century, and the establishment of a Criollism or Hispanism sentiment, which then emerged and were strongly influenced by conservative European thoughts. It also advocated the preservation and supremacy of the Criollos élite culture (Mexicans of full Spanish ancestry) over those of mestizo or indigenous. It was a party of the élite, established by white landowners and aristocrats. The Conservative Party disappeared in 1867, after the fall of Maximilian I of Mexico.[1]

Conservative Party Partido Conservador | |

|---|---|

| Leaders | Anastasio Bustamante Leonardo Márquez Miguel Miramón José Mariano Salas Manuel María Lombardini Juan Almonte |

| Founder | Lucas Alamán |

| Founded | 1849 |

| Dissolved | 1867 |

| Headquarters | Mexico City |

| Ideology | Christian nationalism Conservatism Monarchism Political Catholicism Laissez faire Centralization Nobility's interests Corporatism Feudalism |

| Political position | Right-wing |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Colors | Blue |

Background

Its founder was Lucas Alamán, along with Ignacio Aguilar y Marocho, Francisco de Paula Arrangoiz, Antonio de Haro y Tamariz, Miguel Miramón and Leonardo Márquez, among others, who supported the centralist thinking and insisted that the solution to the Mexican government was a monarchy and not a system of popular election. They hoped to establish a Spanish crown prince in Mexico. Conservatives sought paternalistic support of the kings from Spain, believing that under his rule the Indians would have a "special status" and protection, but the power would remain at hands of the élites and the Mexican nobility.[2]

Ideology

The main point of conflict between liberals and conservatives was the church. Conservatives remained faithful to it and fought for their economic and social power to be maintained. His fighting motto was "Religion and fueros" [3] Among its main tenets was the preserve of Catholicism as a sole religion for all citizens. They also wanted to retain the monopoly of education, to prevent infiltrating liberal ideas. Similarly, they tried to keep military courts thus maintaining their autonomy [4] Conservative ideas were based on moral and religious ideas applied to various fields such as respect for family, traditions, individual and community property. They sought rulers who were honest and worthy bearers of traditional values.[5] Conservatives offered Maximilian of Habsburg the head of the second empire. The mixed liberal-royalist ideology implemented by Emperor Maximilian I disenchanted some conservatives, however, the policies were widely praised by most of the moderate conservatives.

Conservatives

Rulers with conservative ideology [6] who were in power at various stages were:

Presidents (1824-1857)

During the Reform War

Regency of the Second Mexican Empire

- Juan Nepomuceno Almonte (July 11, 1863 - May 20, 1864)

- José Mariano Salas (July 11, 1863 - May 20, 1864)

- Pelagio Antonio de Labastida (July 11, 1863 - November 17, 1863) replaced by Juan Bautista de Ormaechea, Bishop of Tulancingo (November 17, 1863 - May 20, 1864)

- José Ignacio Pavón (July 11, 1863 - January 2, 1864)

First Minister of the Second Mexican Empire

Political strategies

During the Reform War and simultaneous governments Benito Juárez (Liberal Party) and Miguel Miramón (Conservative Party) signed 2 treaties seeking international support:

- The McLane–Ocampo Treaty by liberals

- The Mon-Almonte Treaty by conservatives.

Both which were first signed on December 14, 1859 by Melchor Ocampo and Robert McLane, ambassador of the United States in Mexico. Simultaneously, conservatives sought help from Europe. On September 26, 1859, Juan Nepomuceno Almonte, the Mexican Conservative minister in Paris signed a treaty with Alejandro Mon, Spain's ambassador in France. The Almonte-Mon treaty re-established relations with its former metropoli (Spain).

During the Reform War in Mexico (1858–61), Zuloaga was repeatedly named provisional president by conservatives and abolished the Constitution and the liberal laws affecting the privileges of the church and the lerdo law. In 1860, he began the decline of the Conservative government. On May 10, General Miguel Miramon replaced Zuloaga and sought to defeat the Liberals, but they outnumbered him because unlike conservatives, who only had a presence in the city, also had the support of the Mexican peasantry. Finally they were defeated in the Battle of Capulalpan in December 22, 1860. This battle ended the War of Reform, as a result, Miguel Miramon moved to Cuba and left Benito Juárez as the only president.

In 1861 the governments of Spain, France and Great Britain, after the Treaty of London, faced the Juarez government, which filed for bankruptcy. Liberals managed to convince Spain and England to leave the country peacefully, on the other hand the French sent troops by orders of Napoleon III, and had the aim of establishing a Catholic empire in Mexico to stop the advance of American Protestantism and its growing expansionism. Conservatives supported this policy and strategy that aligned with their interests to establish a monarchy.

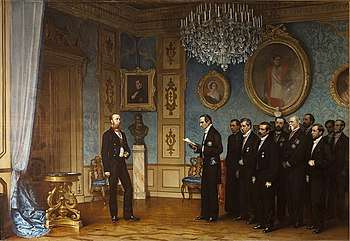

On 10 June 1863 the French army took the city of Mexico. The same year the Conservatives convinced Maximilian of Habsburg to accept the crown of the Mexican empire. After being in power, conservatives noticed that regalist practices of Maximilian resembled closer to liberal than conservative policies, thus he lost a substantial part of its support. This, coupled with the withdrawal of French troops at the approach of the Franco-Prussian war in 1867, as well as the American combatant support for the liberal government of Juarez, who perceived a monarchy in the Mexican territory as a menace for their interests in the region, resulted in a victory for the liberals who ordered to shoot Maximiliano and many conservatives such as Miguel Miramon and Tomas Mejia. Liberals took power and restored the federal republic, with Benito Juárez to the front.[7]

References

- Figueroa Esquer Raúl; “El tiempo eje de México, 1855-1867.” En Estudios. Filosofía, historia, letras, México ITAM, 2012. pp 23-49

- Powell, Gene Thomas; El liberalismo y el campesinado en el centro de México 1850-1876; 1974, México, SEP, Capitulos III y IV

- García Ugarte, Marta Eugenia; Poder político y religioso. México siglo XIX. México, Cámara de Diputados-UNAM-Asoc. Mexicana de Promoción y Cultura Social-Instituto Mexicano de Doctrina Social Cristiana-Miguel Ángel Porrúa, 2010. Dos tomos.

- Mijangos Pablo; El pensamiento religioso de Lucas Alamán, ITAM.

- Alvear Acevedo, Carlos; Historia de México 2ª edición, Limusa Noriega Editores, 2004

- Silva Ortiz, Luz María; “Gobernantes de México ordenados con la cronología presidencial de EUA.” En •Material exclusivo• Luz María Silva.com http://luzmariasilva.com

- McPherson, Edward (1864). The Political History of the United States of America During the Great Rebellion: From November 6, 1860, to July 4, 1864; Including a Classified Summary of the Legislation of the Second Session of the Thirty-sixth Congress, the Three Sessions of the Thirty-seventh Congress, the First Session of the Thirty-eighth Congress, with the Votes Thereon, and the Important Executive, Judicial, and Politico-military Facts of that Eventful Period; Together with the Organization, Legislation, and General Proceedings of the Rebel Administration. Philip & Solomons. p. 349.