Common garter snake

The common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) is a species of natricine snake, which is indigenous to North America and found widely across the continent. Most common garter snakes have a pattern of yellow stripes on a black, brown or green background, and their average total length (including tail) is about 55 cm (22 in), with a maximum total length of about 137 cm (54 in).[2][3] The average body mass is 150 g (5.3 oz).[4] Common garter snakes are also the state reptile of Massachusetts.[5]

| Common garter snake | |

|---|---|

| |

| Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Colubridae |

| Genus: | Thamnophis |

| Species: | T. sirtalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Thamnophis sirtalis | |

| Subspecies | |

|

13 sspp., see text | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

Subspecies

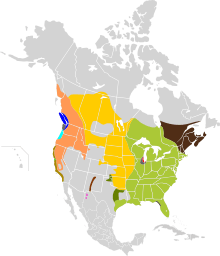

Current scientific classification recognizes 13 subspecies (ordered by date):[6]

- T. s. sirtalis (Linnaeus, 1758) – eastern garter snake

- T. s. parietalis (Say, 1823) – red-sided garter snake

- T. s. infernalis (Blainville, 1835) – California red-sided garter snake

- T. s. concinnus (Hallowell, 1852) – red-spotted garter snake

- T. s. dorsalis (Baird & Girard, 1853) – New Mexico garter snake

- T. s. pickeringii (Baird & Girard, 1853) – Puget Sound garter snake

- T. s. tetrataenia (Cope, 1875) – San Francisco garter snake (endangered)

- T. s. semifasciatus (Cope, 1892) – Chicago garter snake

- T. s. pallidulus Allen, 1899 – maritime garter snake

- T. s. annectens B.C. Brown, 1950 – Texas garter snake

- T. s. fitchi Fox, 1951 – valley garter snake

- T. s. similis Rossman, 1965 – blue-striped garter snake

- T. s. lowei W. Tanner, 1988

Nota bene: A trinomial authority in parentheses indicates that the subspecies was originally described in a genus other than Thamnophis.

Etymology

The subspecific name fitchi is in honor of the American herpetologist Henry Sheldon Fitch.[7]

The subspecific name lowei is in honor of the American herpetologist Charles Herbert Lowe.[8]

The subspecific name pickeringii is in honor of the American naturalist Charles E. Pickering.[9]

Description

Common garter snakes are thin snakes. Few grow over about 4 ft (1.2 m) long, and most stay smaller. Most have longitudinal stripes in many different colors. Common garter snakes come in a wide range of colors, including green, blue, yellow, gold, red, orange, brown, and black.

Life history

The common garter snake is a diurnal snake. In summer, it is most active in the morning and late afternoon; in cooler seasons or climates, it restricts its activity to the warm afternoons.

In warmer southern areas, the snake is active year-round; otherwise, it sleeps in common dens, sometimes in great numbers. On warm winter afternoons, some snakes have been observed emerging from their hibernacula to bask in the sun.

Venom

The saliva of a common garter snake may be toxic to amphibians and other small animals. Garter snakes have a mild venom in their saliva.[10] For humans, a bite is not dangerous, though it may cause slight itching, burning, and/or swelling. Most common garter snakes also secrete a foul-smelling fluid from postanal glands when handled or harmed.

Common garter snakes are resistant to naturally found poisons such as that of the American toad and rough-skinned newt, the latter of which can kill a human if ingested. They have the ability to absorb the toxin from the newts into their bodies, making them poisonous, which can deter potential predators.[11]

The common garter snake uses toxicity for both offense and defense. On the offensive side, the snake's venom can be toxic to some of its smaller prey, such as mice and other rodents.[11] On the defensive side, the snake uses its resistance to toxicity to provide an important antipredator capability.[12] A study on the evolutionary development of resistance of tetrodotoxin tested between two populations of Thamnophis and then tested inside a population of T. sirtalis. Those that were exposed to and lived in the same environment as the newts (Taricha granulosa) that produce tetrodotoxin when eaten were more immune to the toxin (see figure).[12]

While resistance to tetrodotoxin is beneficial in acquiring newt prey, costs are associated with it as well. Consuming the toxin can lead to reduced speed and sometimes no movement for extended periods of time, along with impaired thermoregulation.[13] The antipredator display that this species uses demonstrates the idea of an "arms race" between different species and their antipredator displays.[12] Along the entire geographical interaction of T. granulosa and T. sirtalis, patches occur that correspond to strong coevolution, as well as weak or absent coevolution. Populations of T. sirtalis that do not live in areas that contain T. granulosa contain the lowest levels of tetrodotoxin resistance, while those that do live in the same area have the highest levels of tetrodotoxin resistance. In populations where tetrodotoxin is absent in T. granulosa, resistance in T. sirtalis is selected against because the mutation causes lower average population fitness. This helps maintain polymorphism within garter snake populations.[14]

Reproduction

In the early part of sex, when snakes are coming out of hibernation, the males generally emerge first to be ready when the females wake up. Some males assume the role of a female and lead other males away from the burrow, luring them with a fake female pheromone.[15] After such a male has led rivals away, he "turns" back into a male and races back to the den, just as the females emerge. He is then the first to mate with all the females he can catch. This method also serves to help warm males by tricking other males into surrounding and heating up the male, and is particularly useful to subspecies in colder climates (such as T. s. parietalis).[16] Generally, populations include far more males than females, so during mating season, they form "mating balls", where one or two females are completely swamped by 10 or more males. Sometimes, a male snake mates with a female before hibernation, and the female stores the sperm internally until spring, when she allows her eggs to be fertilized. If she mates again in the spring, the fall sperm degenerate, and the spring sperm fertilize her eggs. The females may give birth ovoviviparously to 12 to 40 young from July through October.

Habitat

The habitat of the common garter snake ranges from forests, fields, and prairies to streams, wetlands, meadows, marshes, and ponds, and it is often found near water. It is found at altitudes from sea level to mountain locations. Depending on the subspecies, the common garter snake can be found as far south the southern-most tip of Florida in the U.S and as far north as the southern-most tip of the Northwest Territories in Canada.

Diet

The diet of T. sirtalis consists mainly of amphibians and earthworms, but also fish, small birds, and rodents. Common garter snakes are effective at catching fast-moving creatures such as fish and tadpoles.

As prey

Animals that prey on the common garter snake include large fish (such as bass and catfish), American bullfrogs, common snapping turtles, larger snakes, hawks, raccoons, foxes, wild turkeys, and domestic cats and dogs.

Conservation

Water contamination, urban expansion, and residential and industrial development are all threats to the common garter snake. The San Francisco garter snake (T. s. tetrataenia), which is extremely scarce and occurs only in the vicinity of ponds and reservoirs in San Mateo County, California, has been listed as an endangered species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service since 1967.

Antipredatory displays

Garter snakes exhibit many different anti-predatory behaviors, or behaviors that ward off predators. Morphology refers to the shape that the snake's body makes in response to the environment, predatory defense, mating, etc. The term body geometry may also be used to describe the shape a snake's body makes. Garter snakes exhibit a higher variation of morphology when compared to other snakes. Predation has been such an intense selection pressure throughout evolution, these snakes have developed body geometries that are highly variable and heritable. These morphologies have been concluded to be highly variable even within a single population.[17] Different geometries indicate whether the snake is preparing to flee, fight, or protect itself. Since the traits are heritable, some evolutionary benefit must exist, such as warding off predators. Different biological factors such as body temperature and sex also influence whether the snake exhibits certain anti-predatory behaviors.[18]

Studies show that the warmer the temperature of a garter snake, the more likely the snake is to flee a predator; a snake with a cooler body temperature remains stationary or attacks. However this is not always true. Male garter snakes are also more likely to flee.[18][19] Garter snakes that exhibit more aggressive antipredatory displays tend to also be fast and have high stamina. However, the cause for correlation is unknown.[20]

As said, temperature can play a part in the anti-predator behavior of the common garter snake.[18] Temperature can also be the factor that determines whether the snake stays passive or attacks when provoked by a predator. For example, one study found that snakes are less likely to escalate in response to an attack when the temperature is lower. One study tested the activity of the snake in response to different temperatures while being provoked by touching or by almost touching. By recording the popular responses as passive or aggressive, the study concluded that as temperature goes down, so does the anti-predator response and general activity of the snake. Thus, temperature is important in determining the snake's anti-predatory responses.[19]

The same study included the idea that the first response of the snake is actually a bluff. When the snake was teased with a finger, the snake reacted aggressively, but once touched, it became passive and did not react with any more violence.[19] This is most likely because the snake will not attack an organism it sees as larger than itself. This behaviour was seen multiple times throughout the course of the experiment. Aposematism, or warning coloration, is another factor that influences anti-predator behavior. For example, the coral snake exhibits aposematic coloration that can be mimicked.[21] While garter snakes do not exhibit mimicry or aposematic coloration, these snakes will freeze until they know they are spotted, then slowly and successively slither away, while spotted and unstriped snakes are more likely to deceptively flee from predators.[22]

The decision of a juvenile garter snake to attack a predator can be affected by whether the snake has just eaten or not. Snakes that have just eaten are more likely to strike a predator or stimulus than snakes that do not have a full stomach. Snakes are more likely to flee a threatening situation if their stomachs are empty. Snakes that have just eaten a large animal are less mobile. Feeding positively affects endurance as opposed to speed.[23]

Another factor that controls the anti-predatory response of the garter snake is where, on its body, the snake is attacked. Many birds and mammals prefer to attack the head of the snake. A research study found that garter snakes are more likely to hide their heads and move their tails back and forth when being attacked close to the head. The same study concluded that snakes that were attacked in the middle of their bodies were more likely to flee or exhibit open-mouthed warning reactions.[24]

Time may be another factor that contributes to anti-predatory responses. Garter snakes are affected by maturation time. As snakes mature, the length of time at which garter snakes can display physical activity at 25 °C increases. Juvenile snakes can only be physically active for 3-5 minutes. Adult snakes can be physically active up to 25 minutes. This is mostly due to aerobic energy production; pulmonary aeration increases up to three times in adult garter snakes when compared to juveniles. The quick fatigue of the juveniles most certainly limits the habitats they can live in, as well as their food sources.[25] It absolutely affects the anti-predator response of both juvenile and adult garter snakes; without sufficient energy production, the snake cannot exhibit any anti-predatory response.

Female garter snakes produce a specific pheromone. Some males of various species of garter snakes exhibit female behavior and morphology. This type of mimicry is primarily found in the red-sided garter snake. A portion of the males that exhibit female mimicry also secrete the sex-specific hormone to attract other males. In a study, these "she-males" mated with females significantly more often than males that did not exhibit this mimicry.[26] A male pretending to be a female around other males increases his chances of reproduction and protects against stronger, more aggressive males.

T. s. sirtalis (Ontario specimen)

T. s. sirtalis (Ontario specimen) T. s. sirtalis (Quebec, Canada)

T. s. sirtalis (Quebec, Canada)- T. s. sirtalis (Florida specimen)

- T. s. pallidulus

See also

- Narcisse Snake Dens

- Inger R.F. (1946). "Restriction of the type locality of Thamnophis sirtalis". Copeia. 1946: 254. doi:10.2307/1438115.

References

- Frost DR, Hammerson GA, Santos-Barrera G (2015). Thamnophis sirtalis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015 doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T62240A68308267.en

- Conant, Roger. (1975). A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America, Second Edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-19979-4. (Thamnophis sirtalis, pp. 157–160 + Plates 23 & 24 + Map 116).

- Eastern Garter Snake (Thamnophis sirtalis). uga.edu

- Fast Facts: Common garter snake. Canadian Geographic

- "Citizen Information Service: State Symbols". Massachusetts State (Secretary of the Commonwealth). Retrieved 2011-01-21.

The Garter Snake became the official reptile of the Commonwealth on January 3, 2007.

- Thamnophis sirtalis , Reptile Database

- Boelens et al., p. 90.

- Beolens et al., p. 161.

- Beolens et al., p. 207.

- "Two things you probably didn't know about garter snakes". Living digitally. 5 May 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- Williams BL, Brodie ED Jr, Brodie ED III (2004). "A resistant predator and its toxic prey: Persistence of newt toxin leads to poisonous (not venomous) snakes". J Chem Ecol. 30 (10): 1901–19. doi:10.1023/b:joec.0000045585.77875.09. PMID 15609827.

- Brodie ED III, Brodie ED Jr (1990). "Tetrodotoxin resistance in garter snakes: an evolutionary response of predators to dangerous prey". Evolution. 44 (3): 651–59. doi:10.2307/2409442. JSTOR 2409442.

- Williams, Becky L.; Brodie Jr., Edmund D.; Brodie III, Edmund D. (2003). "Coevolution of deadly toxins and predator resistance: self-assessment of resistance by garter snakes leads to behavioral rejection of toxic newt prey" (PDF). Herpetologica. 59: 155–163. doi:10.1655/0018-0831(2003)059[0155:codtap]2.0.co;2.

- Brodie Jr., Edmund D.; Ridenhour, B. J.; Brodie III, E. D. (2002). "The evolutionary response of predators to dangerous prey: hotspots and coldspots in the geographic mosaic of coevolution between garter snakes and newts". Evolution. 56 (10): 2067–2082. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2002)056[2067:teropt]2.0.co;2. PMID 12449493.

- Crews, David; Garstka, William R. (1982). "The Ecological Physiology of a Garter Snake". Scientific American. 247: 159–168. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1182-158.

- Mason, Robert T.; Crews, David (1985). "Female Mimicry in Garter Snakes" (PDF). Nature. 316 (6023): 59–60. doi:10.1038/316059a0. PMID 4010782.

- Garland, T. (1988). "Genetic Basis of Activity Metabolism. I. Inheritance of Speed, Stamina & Antipredator Display in the Garter Snake, Thamnophis sirtalis" (PDF). Evolution. 42 (2): 335–350. doi:10.2307/2409237.

- Shine, R.; M.M. Olsson; M.P. Lesmaster; I.T. Moore & R.T. Mason (1999). "Effects of Sex, Body, Size, Temperature & Location on the Antipredator Tactics of Free-Ranging Garter Snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis, Colubridae)". Oxford Journal. 11 (3): 239–245. doi:10.1093/beheco/11.3.239.

- Schieffelin, C. D.; de Queiroz, A. (1991). "Temperature and defense in the common garter snake: warm snakes are more aggressive than cold snakes". Herpetologica. 47: 230–237. JSTOR 3892738.

- Brodie III, E.D. (1992). "Correlational Selection For Color Pattern & Antipredator Behavior In The Garter Snake". Evolution. 46 (5): 1284–1298. doi:10.2307/2409937. JSTOR 2409937.

- Greene, H.W.; McDiarmid, R.W. (1981). "Coral Snake Mimicry: Does It Occur?". Science. 213 (4513): 1207–1212. doi:10.1126/science.213.4513.1207. PMID 17744739.

- Arnold, S.J.; Bennett, A.F. (1984). "Behavioural Variation in Natural Population III: Antipredator Display in the Garter Snake Thamnophis radix" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 32 (4): 1108–1118. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(84)80227-4.

- Herzog, Harold A. Jr.; Bailey, Bonnie D. (1987). "Development of Antipredator Responses in Snakes: II. Effects of recent feeding on defensive behaviors of juvenile garter snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis)". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 101 (4): 387–389. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.101.4.387.

- Langkilde, Tracy; Shine, Richard; Mason, Robert T. (2004). "Predatory Attacks to the Head vs. Body Modify Behavioral Responses of Garter Snakes". Ethology. 110 (12): 937–947. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2004.01034.x.

- Pough, F. Harvey (1977). "Ontogenetic Change in Blood Oxygen Capacity and Maximum Activity in Garter Snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis)". Journal of Comparative Physiology. 116 (3): 337–345. doi:10.1007/BF00689041.

- Mason, Robert T.; Crews, David (1985). "Female Mimicry in Garter Snakes". Nature. 316 (6023): 59–60. doi:10.1038/316059a0. PMID 4010782.

Bibliography

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5.

External links

- "Thamnophis sirtalis ". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 6 February 2006.

- Care of Garter Snakes

- Garter Snake Information

- Caring for Your Garter Snake

- Herzog HA, Bowers BB, Burghardt GM (1989). "Stimulus control of antipredator behavior in newborn and juvenile garter snakes (Thamnophis)". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 103 (3): 233–242. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.103.3.233.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thamnophis sirtalis. |

![]()

- Eastern Garter Snake at Ontario Nature.

- Red-sided Garter Snake at Ontario Nature.

Further reading

- Conant, Roger; Bridges, William (1939). What Snake Is That? A Field Guide to the Snakes of the United States East of the Rocky Mountains. (with 108 drawings by Edmond Malnate). New York and London: D. Appleton Century Company. Frontispiece map + viii + 163 pp. + Plates A-C, 1-32. (Thamnophis sirtalis, pp. 124–126 + Plate 24, figures 70-72).

- Linnaeus C (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, diferentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio Decima, Reformata. Stockholm: L. Salvius. 824 pp. (Coluber sirtalis, new species, p. 222). (in Latin).

- Powell R, Conant R, Collins JT (2016). Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America, Fourth Edition. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. xiv + 494 pp., 47 plates, 207 figures. ISBN 978-0-544-12997-9. (Thamnophis sirtalis, pp. 431–433 + Plate 43).

- Schmidt, Karl P.; Davis, D. Dwight (1941). Field Book of Snakes of the United States and Canada. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. 365 pp., 34 plates, 103 figures. (Thamnophis sirtalis, pp. 252–255 + Plate 26).

- Smith HM, Brodie ED Jr (1982). Reptiles of North America: A Guide to Field Identification. New York: Golden Press. 240 pp. ISBN 0-307-13666-3. (Thamnophis sirtalis, pp. 148–149).

- Stebbins RC (2003). A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians, Third Edition. The Peterson Field Guide Series ®. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. xiii + 533 pp., 56 plates. ISBN 978-0-395-98272-3. (Thamnophis sirtalis, pp. 375–377 + Plate 48 + Map 162).

- Wright, Albert Hazen; Wright, Anna Allen (1957). Handbook of Snakes of the United States and Canada. Ithaca and London: Comstock Publishing Associates, a division of Cornell University Press. 1,105 pp. (in 2 volumes). (Thamnophis sirtalis, pp. 834–863, Figures 242-248, Map 60).