Common barbel

The common barbel, Barbus barbus, is a species of freshwater fish belonging to the family Cyprinidae. It shares the common name 'barbel' with its many relatives in the genus Barbus, of which it is the type species. In Great Britain it is usually referred to simply as the barbel; similar names are used elsewhere in Europe, such as barbeau in France and flodbarb in Sweden.[2] The name derives from the four whiskerlike structures located at the corners of the fish's mouth, which it uses to locate food.

| Common barbel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Cypriniformes |

| Family: | Cyprinidae |

| Subfamily: | Barbinae |

| Genus: | Barbus |

| Species: | B. barbus |

| Binomial name | |

| Barbus barbus | |

| Synonyms | |

Distribution and habitat

B. barbus is native throughout northern and eastern Europe, ranging north and east from the Pyrénées and Alps to Lithuania, Russia and the northern Black Sea basin.[3] It is an adaptable fish which transplants well between waterways, and has become established as an introduced species in several countries including Scotland,[4] Morocco and Italy.[5] Although barbel are native to eastern flowing rivers in England, they have historically been translocated to western flowing rivers, such as the River Severn.[6] Its favoured habitats are the so-called barbel zones in fast-flowing rivers with gravel or stone bottoms, although it regularly occurs in slower rivers and has been successfully stocked in stillwaters.[7]

Barbel are very abundant in some rivers, often seen in large shoals on rivers such as the Wye.[8] Izaak Walton reported that there were once so many barbel in the Danube that they could be caught by hand, 'eight or ten load at a time' .[9]

Ecology

Adult B. barbus specimens can reach 1.2 m (4 ft) in length and 12 kg (26 lb) in weight, although it is typically found at smaller sizes (50–100 cm length, weight 1–3 kg).[10] Adult barbel can live to over 20 years of age.[11] Their sloping foreheads, flattened undersides, slender bodies and horizontally oriented pectoral fins are all adaptations for their life in swift, deep rivers, helping to keep them close to the riverbed in very strong flows. Juvenile fish are usually grey and mottled in appearance; adults are typically dark brown, bronze or grey in colour with a pale underside, with distinctively reddish or orange-tinged fins. The lobes of the tail are asymmetrical, the lower lobe being rounded and slightly shorter than the pointed upper lobe.

Barbel commonly feed at night, although they may feed during the daytime in the safety of deeper water or near underwater obstructions.[12] Their underslung mouths make them especially well adapted for feeding on benthic organisms, including crustaceans, insect larvae and mollusks, which they root out from the gravel and stones of the riverbed. Barbel diets change as the fish develop from young of the year to juveniles and then to adults.[13] As young of the year the diatoms that cover rocks and the larvae of non-biting midges (Chironomids) are particularly important foods.[14]

Males become mature after three to four years, females after five to eight years. Spawning occurs between May and late June on most rivers, when groups of males assemble in shallow water in pursuit of mates. Upstream migration to reach spawning grounds can happen between March and May, but will depend on the temperature.[15] Like many fish species, male barbel develop distinctive tubercles on their heads prior to spawning.[16] Females produce between 8,000 and 12,000 eggs per kilogram of bodyweight, which are fertilised by males as they are released and deposited in shallow excavations in the gravel of the riverbed. Individual barbel can move between 16 and 68 km in a year, with mean (average) daily movement between 26 and 139m.[15]

Parasites of Barbus barbus include Aspidogaster limacoides, a trematode flatworm;,[17] Eustrongylides sp. a nematode and Pomphorhynchus laevis, an acanthocephalan worm.[18][19]

As food

Many authors have noted the highly toxic nature of barbel roe when eaten by humans, including Dame Juliana Berners and Charles David Badham.[20][21] Badham relates the experience of Italian physician Antonio Gazius, who, he says, "took two boluses, and thus describes his sensations: 'At first I felt no inconvenience, but some hours having elapsed, I began to be disagreeably affected, and as my stomach swelled, and could not be brought down again by anise or carminatives, I was soon in a state of great depression and distress.' His countenance was pallid, like a man in a swoon, deadly coldness ensued, violent cholera and vomiting came after until the roe was passed, and then he became all right."

Despite the risks associated with eating barbel and its roe during the spawning season, several notable cookery authors have included recipes for barbel in their books. Mrs Beeton, for example, writes that they are in season in the winter months, and suggests simmering them with port and herbs.[22]

Recreational importance

The common barbel is a popular sport fish throughout its range, long prized by anglers for its power and stamina. Izaak Walton noted that "he will often break both rod and line if he proves to be a big one ... the Barbel affords an angler choice sport, being a lusty and a cunning fish; so lusty and cunning as to endanger the breaking of the angler's line, by running his head forcibly towards any covert, or hole, or bank, and then striking at the line, to break it off, with his tail".[9]

Barbel fishing is especially popular in the UK, where it reaches a weight of over 9 kg (20 lb).[23] A fish of more than 4.5 kg (10 lb) is considered to be of specimen size. Famous UK barbel rivers include the Hampshire Avon, Dorset Stour, Trent, Kennet, Wye, Severn, and Great Ouse. Several angling societies exist in the UK which specifically promote the pursuit and conservation of the species, including the Barbel Society and the Barbel Catchers Club.

Baits for catching barbel vary widely according to local practices and conditions. In the UK, popular baits include tinned luncheon meat, fishmeal-based pellets, hemp seed, maggots, and boilies. In areas with high angling activity fishmeal-based pellets could constitute up to 71% of the barbel diet.[24] In France, many anglers still use natural baits, especially caddis larvae, which they collect from the stones and gravel near the fish's feeding areas.[25]

References

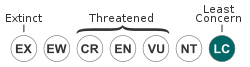

- Freyhof, J. & Kottelat, M. (2008). "Barbus barbus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 2010-02-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Common Names List - Barbus barbus". www.fishbase.de. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2006). "Barbus barbus" in FishBase. March 2006 version.

- "Barbel Barbus Barbus". Scottish Federation for Coarse Angling. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- "Introductions of Barbus barbus". Fishbase.org. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- Antognazza, Caterina Maria; Andreou, Demetra; Zaccara, Serena; Britton, Robert J. (March 2016). "Loss of genetic integrity and biological invasions result from stocking and introductions of Barbus barbus: insights from rivers in England". Ecology and Evolution. 6 (5): 1280–1292. doi:10.1002/ece3.1906. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 4729780. PMID 26843923.

- "Stillwater Barbel Thrive". Match Fishing Magazine. 24 November 2011. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- "Other Fish Species". Wye & Usk Foundation. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- Izaak Walton (1869). A. Murray (ed.). The Compleat Angler. F. Warne. pp. 86–87.

- "Barbel". Environment Agency archive. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- Amat Trigo, F.; et al. (2017). "Spatial variability in the growth of invasive European barbel Barbus barbus in the River Severn basin, revealed using anglers as citizen scientists" (PDF). Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems. 418: 6.

- Alwyne C. Wheeler (1969). The Fishes of the British Isles and North-West Europe. Macmillan.

- Gutmann Roberts, Catherine; Britton, J. Robert (2018-09-01). "Trophic interactions in a lowland river fish community invaded by European barbel Barbus barbus (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae)". Hydrobiologia. 819 (1): 259–273. doi:10.1007/s10750-018-3644-6. ISSN 1573-5117.

- Gutmann Roberts, Catherine; Britton, J. Robert (2018). "Quantifying trophic interactions and niche sizes of juvenile fishes in an invaded riverine cyprinid fish community" (PDF). Ecology of Freshwater Fish. 27 (4): 976–987. doi:10.1111/eff.12408. ISSN 1600-0633.

- Gutmann Roberts, Catherine; Hindes, Andrew M.; Britton, J. Robert (2019-01-03). "Factors influencing individual movements and behaviours of invasive European barbel Barbus barbus in a regulated river". Hydrobiologia. 830: 213–228. doi:10.1007/s10750-018-3864-9. ISSN 1573-5117.

- Wiley, Martin L; Collette, Bruce B (27 November 1970). "Breeding tubercles and contact organs in fishes: their occurrence, structure, and significance". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 43.

- Schludermann C., Laimgruber S., Konecny R. & Schabuss M. (2005). "Aspidogaster limacoides DIESING, 1835 (Trematoda, Aspidogastridae): A new parasite of Barbus barbus (L.) (Pisces, Cyprinidae) in Austria". Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien 106B: 141-144

- Nachev, Milen; Jochmann, Maik A.; Walter, Friederike; Wolbert, J. Benjamin; Schulte, S. Marcel; Schmidt, Torsten C.; Sures, Bernd (2017-02-17). "Understanding trophic interactions in host-parasite associations using stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen". Parasites & Vectors. 10 (1): 90. doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2030-y. ISSN 1756-3305. PMC 5316170. PMID 28212669.

- Djikanovic; Gacic & Cakic (2010). "Endohelminth fauna of barbel Barbus barbus in the Serbian section of the Danube River" (PDF). Bulletin of the European Association of Fish Pathologists. 30 (6): 229–236. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- David Badham (1854). Prose Halieutics: Or, Ancient and Modern Fish Tattle. J. W. Parker and son. p. 81. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- John Harrington Keene (1881). The Practical Fisherman: Dealing with the Natural History, the Legendary Lore, the Capture of British Freshwater Fish, and Tackle and Tackle Making. Bazaar Office. pp. 80–81. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- Mrs. Beeton (Isabella Mary) (1861). The Book of Household Management. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. p. 229. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- "Britain's biggest barbel fish, the Big Lady, killed by otter". The Telegraph. 30 July 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- Gutmann Roberts, Catherine; Bašić, Tea; Trigo, Fatima Amat; Britton, J. Robert (2017). "Trophic consequences for riverine cyprinid fishes of angler subsidies based on marine-derived nutrients" (PDF). Freshwater Biology. 62 (5): 894–905. doi:10.1111/fwb.12910. ISSN 1365-2427.

- John Bailey (24 April 2000). "French Barbel". Fishing.co.uk. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barbus barbus. |