Clarence Earl Gideon

Clarence Earl Gideon (August 30, 1910 – January 18, 1972) was a poor drifter accused in a Florida state court of felony theft. His case resulted in the landmark 1963 U.S. Supreme Court decision Gideon v. Wainwright, holding that a criminal defendant who cannot afford to hire a lawyer must be provided one at no cost.

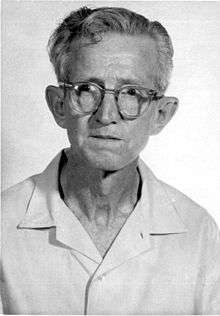

Clarence Earl Gideon | |

|---|---|

Clarence Earl

Gideon circa 1961 | |

| Born | August 30, 1910 |

| Died | January 18, 1972 (aged 61) |

| Criminal status | acquitted |

| Conviction(s) | robbery, burglary, larceny, theft (multiple) |

| Criminal penalty | multiple sentences |

At Gideon's first trial in August 1961, he was denied legal counsel and was forced to represent himself and was convicted. After the Supreme Court ruled in Gideon that the state had to provide defense counsel in criminal cases at no cost to the indigent, Florida retried Gideon. At his second trial, which took place in August 1963, with a court-appointed lawyer representing him and bringing out for the jury the weaknesses in the prosecution's case, Gideon was acquitted.

Early life

Clarence Earl Gideon was born in Hannibal, Missouri. His father, Charles Roscoe Gideon, died when he was three. His mother, Virginia Gregory Gideon, married Marrion Anderson shortly after. Gideon, after years of defiant behavior and chronic 'playing hooky', quit school after eighth grade, aged 14, and ran away from home, living as a homeless drifter. By the time he was sixteen, Gideon had begun compiling a petty crime profile.

He was arrested in Missouri and charged with robbery, burglary, and larceny. Gideon was sentenced to 10 years but released after three, in 1932, just as the Great Depression was beginning.

Gideon spent most of the next three decades in poverty. He served some more prison terms at Leavenworth, Kansas for stealing government property; in Missouri for stealing, larceny and escape; and in Texas for theft.

Between his prison terms Gideon was married four times. The first few marriages ended quickly, but the fourth to Ruth Ada Babineaux in October 1955 lasted. They settled in Orange, Texas in the mid-1950s and Gideon found irregular work as a tugboat laborer and bartender until he was bedridden by tuberculosis for three years.

In addition to three children that Ruth already had, Gideon and Ruth had three children, born in 1956, 1957, and 1959: the first two in Orange, the third after the family had moved to Panama City, Florida. The six children were later removed by welfare authorities. Gideon started working as an electrician in Florida, but began gambling for money because of his low wages. He did not serve any more time in jail until 1961.

Arrest, conviction, and Gideon v. Wainwright

Arrest

On June 3, 1961, $5 in change and a few bottles of beer and soda were stolen from the Pool Room, a pool hall and beer bar that belonged to Ira Strickland Jr. Strickland also alleged that $50 was taken from the jukebox. Henry Cook, a 22-year-old resident who lived nearby, told the police that he had seen Gideon walk out of the bar with a bottle of wine and his pockets filled with coins, and then get into a cab. Gideon was later arrested in a tavern.

First trial

Being too poor to pay for counsel, Gideon was forced to defend himself at his trial after being denied a lawyer by the trial judge, Robert McCrary Jr. At that time, Florida law only gave indigent defendants no-cost legal counsel in death penalty cases. On August 4, 1961, Gideon was convicted of breaking and entering with intent to commit petty larceny, and on August 25, Judge McCrary gave Gideon the maximum sentence, five years in state prison.

Gideon v. Wainwright

While incarcerated, Gideon studied the American legal system. He concluded that Judge McCrary had violated his constitutional right to counsel under the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution, applicable to Florida through the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. He then wrote to an FBI office in Florida and then to the Florida Supreme Court, but was denied assistance. In January 1962, he mailed a five-page petition for writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court of the United States, asking the nine justices to consider his case.[1] The Supreme Court agreed to hear his appeal. Originally, the case was called Gideon v. Cochran and was argued on January 15, 1963. Gideon v. Cochran was changed to Gideon v. Wainwright after Louie L. Wainwright replaced H. G. Cochran as the director of the Florida Division of Corrections.

Abe Fortas (later a Supreme Court justice) was assigned to represent Gideon. Florida Attorney General Bruce Jacob was assigned to argue against Gideon. Fortas argued that a common man with no training in law could not go up against a trained lawyer and win, and that "you cannot have a fair trial without counsel." Jacob argued that the issue at hand was a state issue, not federal; the practice of only appointing counsel under "special circumstances" in non-capital cases sufficed; that thousands of convictions would have to be thrown out if it were changed; and that Florida had followed for 21 years "in good faith" the 1942 Supreme Court ruling in Betts v. Brady.

The Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Gideon's favor in a landmark decision on March 18, 1963.[2]

Second trial

About 2,000 convicted people in Florida alone were freed as a result of the Gideon decision; Gideon himself was not freed, but instead received another trial.

He chose W. Fred Turner to be his lawyer for his retrial, which occurred on August 5, 1963, five months after the Supreme Court ruling. During the trial, Turner picked apart the testimony of eyewitness Henry Cook, and in his opening and closing statements suggested the idea that Cook likely had been a lookout for a group of young men who had stolen the beer and coins from the Bay Harbor Pool Room. (Turner had been Cook's lawyer in previous cases.[3])

Turner also received a statement from the taxicab driver who transported Gideon from the Bay Harbor Pool Room to a bar in Panama City, stating that Gideon was carrying neither wine, beer, nor Coke when he picked him up, even though Cook testified that he watched Gideon walk from the pool hall to the phone, then wait for a cab. Furthermore, although in the first trial Gideon had not cross-examined the driver about his statement that Gideon had told him to keep the taxi ride a secret, Turner's cross-examination revealed that Gideon had said that to the cab driver previously because "he had trouble with his wife."[3]

The jury acquitted Gideon after one hour of deliberation.[4]

Legacy

In 1963, Robert F. Kennedy remarked about the case:

If an obscure Florida convict named Clarence Earl Gideon had not sat down in prison with a pencil and paper to write a letter to the Supreme Court; and if the Supreme Court had not taken the trouble to look at the merits in that one crude petition among all the bundles of mail it must receive every day, the vast machinery of American law would have gone on functioning undisturbed. But Gideon did write that letter; the court did look into his case; he was re-tried with the help of competent defense counsel; found not guilty and released from prison after two years of punishment for a crime he did not commit. And the whole course of legal history has been changed.[5]

Later life

After his acquittal, Gideon resumed his previous way of life and married for a fifth time some time later. He died of cancer in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, on January 18, 1972, at age 61. Gideon's family had him buried in an unmarked grave in Hannibal. The local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union later added a granite headstone, inscribed with a quote from a letter Gideon wrote to his attorney Abe Fortas, "Each era finds an improvement in law for the benefit of mankind."

Portrayal on film

Gideon was portrayed by Henry Fonda in the 1980 made-for-television film Gideon's Trumpet, based on Anthony Lewis' book of the same name. The film was first telecast as part of the Hallmark Hall of Fame anthology series, and co-starred Jose Ferrer as Abe Fortas, the attorney who pleaded Gideon's right to have a lawyer in the US Supreme Court. Fonda was nominated for an Emmy Award for his portrayal of Gideon.

See also

- Miranda v. Arizona (1966)

References

- Gideon, Clarence Earl (June 5, 1962). "Petition from Clarence Gideon." Archived 2013-03-03 at the Wayback Machine National Archives Transcription Pilot Project.

- "State Must Pay Lawyers for Poor". The Miami News. March 18, 1963. p. 1.

- Lewis, Anthony (April 20, 2003). "The Silencing of Gideon's Trumpet". The New York Times.

- "Gideon Happy After Acquittal In Famed Case". St. Petersburg Times. August 6, 1963. p. 1-B.

- Kennedy, Robert (1963). "Clarence Earl Gideon v. Wainwright, U.S. Supreme Court, 1963: A Landmark in the Law". Division of Public Defender Services, State of Connecticut.

External links

- State of Florida vs Clarence Earl Gideon (transcript of second trial, August 5, 1963) from Florida's Fourteenth Judicial Circuit.

- King, Jack (June 2012). "Clarence Earl Gideon: Unlikely World-Shaker". The Champion. National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. p. 58.

- Clarence Earl Gideon, Petitioner, vs. Louis L. Wainwright, Director, Department of Corrections, Respondent