Chloride cell

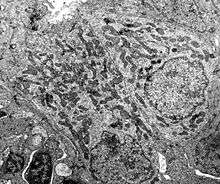

Chloride cells (now called ionocytes) are mitochondrion-rich cells within teleost fish gills that are responsible for maintaining optimal osmotic, ionic, and acid-base levels within the fish. By expending energy to power the enzyme Na+/K+-ATPase and in coordination with other protein transporters, marine teleost ionocytes pump excessive sodium and chloride ions against the concentration gradient into the ocean.[1][2][3] Conversely, freshwater teleost ionocytes use this low intracellular environment to attain sodium and chloride ions into the organism, and also against the concentration gradient.[1][3] In larval fishes with underdeveloped / developing gills, ionocytes can be found on the skin and fins.[4][5][6]

Mechanism of action

Marine teleost fishes consume large quantities of seawater to reduce osmotic dehydration.[7] The excess of ions absorbed from seawater is pumped out of the teleost fishes via the chloride cells.[7] These cells use active transport on the basolateral (internal) surface to accumulate chloride, which then diffuses out of the apical (external) surface and into the surrounding environment.[8] Such mitochondrion-rich cells are found in both the gill lamellae and filaments of teleost fish. Using a similar mechanism, freshwater teleost fish use these cells to take in salt from their dilute environment to prevent hyponatremia from water diffusing into the fish.[8]

References

- Evans DH, Piermarini PM, Choe KP (January 2005). "The multifunctional fish gill: dominant site of gas exchange, osmoregulation, acid-base regulation, and excretion of nitrogenous waste". Physiological Reviews. 85 (1): 97–177. doi:10.1152/physrev.00050.2003. PMID 15618479.

- Marshall WS (August 2002). "Na(+), Cl(-), Ca(2+) and Zn(2+) transport by fish gills: retrospective review and prospective synthesis". The Journal of Experimental Zoology. 293 (3): 264–83. doi:10.1002/jez.10127. PMID 12115901.

- Hirose S, Kaneko T, Naito N, Takei Y (December 2003). "Molecular biology of major components of chloride cells". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part B, Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 136 (4): 593–620. doi:10.1016/s1096-4959(03)00287-2. PMID 14662288.

- Glover CN, Bucking C, Wood CM (October 2013). "The skin of fish as a transport epithelium: a review". Journal of Comparative Physiology. B, Biochemical, Systemic, and Environmental Physiology. 183 (7): 877–91. doi:10.1007/s00360-013-0761-4. PMID 23660826.

- Kwan GT, Wexler JB, Wegner NC, Tresguerres M (February 2019). "Ontogenetic changes in cutaneous and branchial ionocytes and morphology in yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) larvae". Journal of Comparative Physiology. B, Biochemical, Systemic, and Environmental Physiology. 189 (1): 81–95. doi:10.1007/s00360-018-1187-9. PMID 30357584.

- Varsamos S, Nebel C, Charmantier G (August 2005). "Ontogeny of osmoregulation in postembryonic fish: a review". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part A, Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 141 (4): 401–29. doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2005.01.013. PMID 16140237.

- Allaby M. "Chloride cells". A Dictionary of Zoology. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- Wilmer P, Stone G, Johnston I (2005). Environmental Physiology of Animals. Malden, MA: Blackwell. pp. 85. ISBN 978-1-4051-0724-2.

Further reading

- Zadunaisky JA (June 1996). "Chloride cells and osmoregulation". Kidney International. 49 (6): 1563–7. doi:10.1038/ki.1996.225. PMID 8743455.