Chicken War

Chicken War or Hen War (Polish: Wojna kokosza) is the colloquial name for a 1537 anti-royalist and anti-absolutist rokosz (rebellion) by the Polish nobility. The derisive name was coined by the magnates, who for the most part supported the King and claimed that the conflict's only effect was the near-extinction of the local chickens, eaten by the nobles gathered for the rokosz at Lwów, in Ruthenian Voivodeship.[1][2] The magnates' choice of "kokosz"—meaning "an egg laying hen"—may have been inspired by a play on words between "kokosz" and the similar-sounding "rokosz". The Chicken War was the first rokosz of the Szlachta in Polish history.[3]

Backgrounds

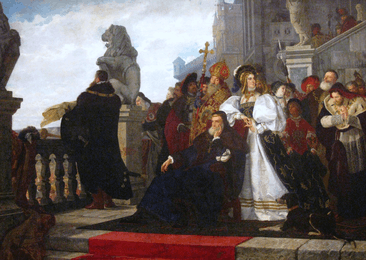

At the start of his reign, King Sigismund I the Old inherited a Kingdom of Poland with a century-long tradition of liberties of the nobility, confirmed in numerous privileges. Sigismund faced the challenge of consolidating internal power to handle external threats to the country. During the rule of his predecessor, Alexander I, the statute of "Nihil novi" had been instituted, effectively forbidding kings of Poland to promulgate laws without the consent of the Parliament.[4] This proved crippling to Sigismund's dealings with his nobles and magnates, as well as a serious threat to the country's stability. To strengthen his power, Sigismund initiated a set of reforms, establishing a permanent conscription army in 1527 and extending the bureaucratic apparatus necessary to govern the state and finance the army. Supported by his Italian consort, Bona Sforza, he began buying up land to enlarge the royal treasury.[5] He also initiated a process of restitution of royal properties, previously pawned or rented to the nobles.

The Rokosz

In 1537, however, the King's policies led to a major conflict. The nobility, gathered near Lwów to meet with a levée en masse, called for a military campaign against Moldavia. However, the lesser and middle strata of the nobility called a rokosz, or semi-legal rebellion, to force the King to abandon his reforms. According to contemporary accounts, 150,000 militia had been assembled for the rebellion. [6]The nobles presented him with 36 demands, most notably:

- A cessation of further land acquisitions by Queen Bona Sforza;

- Exemption of the nobility from the tithes;

- A cleanup of the Treasury rather than its expansion;

- Confirmation and extension of the privileges of the nobility;

- Lifting of the toll or exemption of the nobility from it;

- Adoption of a law concerning incompatibilitas—the incompatibility of certain offices that were not to be joined in the same hand (for instance, that of a Starosta and of a Palatine or Castellan);

- The carrying out of a law requiring the appointment of only the local nobles to most important local offices; and

- The creation of a body of permanent advisors to the king.

Finally, the protesters criticized the role of Queen Bona, whom they blamed for the "bad education" of young Prince Sigismund Augustus (the future King Sigismund II),[7] as well as for seeking to increase her power and influence in the state.[8]

It soon transpired, however, that the nobility's leaders were divided and that achieving a compromise was almost impossible.[9] Too weak to start a civil war against the King, the protesters finally agreed to what was thought a compromise. The King rejected most of their demands, while accepting the principle of incompatibilitas the following year and agreeing not to force the election of the future king vivente rege, that is, in the lifetime of the reigning king.[8]

Thereupon the nobility returned to their homes, having achieved little.[6]

See also

- Lubomirski's Rokosz

- Rokosz

- Zebrzydowski's Rokosz

References

- Early Modern Wars 1500–1775. Amber Books Ltd. September 17, 2013. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-78274-121-3.

- Samsonowicz, Henryk (1976). Historia Polski do roku 1795 [History of Poland to 1795] (in Polish). Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne. p. 157.

- Na podstawie: Stanisław Rosik, Przemysław Wiszewski, Poczet polskich królów i książąt, Wrocław 2004, str. 215

- Wagner, W.J. (1992). "May 3, 1791, and the Polish constitutional tradition". The Polish Review. 36 (4): 383–395. JSTOR 25778591.

- Kosior, Katarzyna (2018). "Bona Sforza and the Realpolitik of Queenly Counsel in Sixteenth-Century Poland-Lithuania". Queenship and Counsel in Early Modern Europe. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 16, 17. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-76974-5_2. ISBN 978-3-319-76973-8.

- Bronikowski, Alexander (1834). The Court of Sigismund Augustus, Or Poland in the Sixteenth Century. Longmans, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green and Longman. p. 46.

- Kosior, Katarzyna (2016). "Outlander, Baby Killer, Poisoner? Rethinking Bona Sforza's Black Legend". Virtuous or Villainess? The Image of the Royal Mother from the Early Medieval to the Early Modern Era. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. p. 208. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-51315-1_10. ISBN 978-1-137-51314-4.

Zborowski claimed that the young king should have a separate court rather than being a part of his mother’s establishment and be taught to enjoy manly entertainments instead of spending time in the company of women.

- Kosior, Katarzyna (2018). "Bona Sforza and the Realpolitik of Queenly Counsel in Sixteenth-Century Poland-Lithuania". Queenship and Counsel in Early Modern Europe. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 22–23. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-76974-5_2. ISBN 978-3-319-76973-8.

- Walek, Janusz, (1987). Dzieje Polski w malarstwie i poezji (in Polish). Wydawn. Interpress. p. 77. ISBN 83-223-2114-7. OCLC 246756060.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)