Chevalier de Saint-Georges

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (December 25, 1745 – June 12, 1799)[1] was a champion fencer, classical composer, virtuoso violinist, and conductor of the leading symphony orchestra in Paris. Born in the French colony of Guadeloupe, he was the son of George Bologne de Saint-Georges, a wealthy married planter, and Anne dite Nanon, his wife's African slave.[2]

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges | |

|---|---|

Saint-Georges by Mather Brown, 1787 | |

| Born | December 25, 1745 |

| Died | June 10, 1799 (aged 53) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | Académie royale polytechnique des armes et de l’équitation |

His father took him to France when he was young, and he was educated there, also becoming a champion fencer. During the French Revolution, the younger Saint-Georges served as a colonel of the Légion St.-Georges,[3] the first all-black regiment in Europe. He fought on the side of the Republic. Today the Chevalier de Saint-Georges is best remembered as the first known classical composer of African ancestry; he composed numerous string quartets and other instrumental music, and opera.

Early life

Born in Baillif, Basse-Terre in 1745, Joseph Bologne was the son of planter and former councilor at the parliament of Metz Georges de Bologne Saint-Georges (1711–1774) and Anne, dite Nanon, his wife's 16-year-old African slave of Senegalese origin, who served as her personal maid.[4] Bologne was legally married to Elisabeth Mérican (1722–1801) but acknowledged his son by Nanon and gave him his surname.[5][6][7]

His father, called "de Saint-Georges" after one of his plantations in Guadeloupe, was a commoner until 1757, when he acquired the title of Gentilhomme ordinaire de la chambre du roi (Gentleman of the king’s chamber).[8] Saint-George was ineligible, under French law, for any titles of nobility due to his African mother.[9] Starting in the 17th century, a Code Noir had been law in France and its colonial possessions. On April 5, 1762, King Louis XV decreed that "Negres et gens de couleur" (blacks and people of color) must register with the clerk of the Admiralty within two months.[10] Even leading Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire argued that Africans and their descendants were inferior to White Europeans.[11] These laws and racial attitudes towards people of color made it impossible for Joseph Bologne to marry anybody at his level of society, though he did have at least one serious romantic relationship.[12]

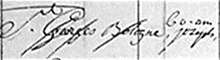

(Misled by Roger de Beauvoir's 1840 romantic novel Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges,[13] most of his biographers confused Joseph’s father with Jean de Boullonges, Controller-General of Finances between 1757 and 1759. This led to the erroneous spelling of Saint-Georges’ family name as "Boulogne", persisting to this day, even in records in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.)

_landing_in_France%2C_August_7%2C_1753.jpeg)

In 1753, his father took Joseph, aged seven, to France for his education, installing him in a boarding school, and returned to his lands on Guadeloupe.[14] Two years later, on August 26, 1755, listed as passengers on the ship L’Aimable Rose, Bologne de Saint-Georges and Negresse Nanon landed in Bordeaux.[15] In Paris, reunited with their son Joseph, they moved into a spacious apartment in the St. Germain neighborhood at 49 rue Saint André de Arts.[16][17]

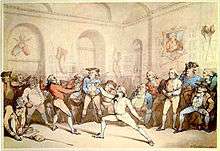

At age 13, Joseph was enrolled by his father in Tessier de La Boëssière’s Académie royale polytechnique des armes et de ‘l’équitation (fencing and horsemanship). According to La Boëssière fils, son of the Master: “At 15 his [Bologne's] progress was so rapid, that he was already beating the best swordsmen, and at 17 he developed the greatest speed imaginable.”[18] Bologne was still a student when he beat Alexandre Picard, a fencing-master in Rouen, who had been mocking him as "Boëssière's mulatto", in public. That match, bet on heavily by a public divided into partisans and opponents of slavery, was an important coup for Bologne. His father, proud of his feat, rewarded Joseph with a handsome horse and buggy.[19] In 1766 on graduating from the Royal Polytechnique Academy, Bologne was made a Gendarme du roi (officer of the king’s bodyguard) and a chevalier.[20] Henceforth Joseph Bologne, by adopting the suffix of his father, would be known as the "Chevalier de Saint-Georges". As an illegitimate son, he was prevented from inheriting his father's title.

In 1764 when, at the end of the Seven Years' War, Georges Bologne returned to Guadeloupe to look after his plantations. The following year, he made a last will and testament where he left Joseph an annuity of 8000 francs and an adequate pension to Nanon, who remained with their son in Paris.[19] When his father died in 1774 in Guadeloupe, Georges awarded his annuity to his legitimate daughter, Elisabeth Benedictine.

Long before her death, Saint-George's mother, Anne Nanon, would also record a testamentary deed dated June 18, 1778, in which she gives and bequeaths all her belongings. However, according to biographer Pierre Bardin, she signed "Anne Danneveau," and refers to her son as "Mr. De Boulonge St-George," reflecting her desire to distance herself from her son thus further conceal Saint-George's African origins.[21]

According to Bologne's friend, Louise Fusil: "... admired for his fencing and riding prowess, he served as a model to young sportsmen ... who formed a court around him."[22] A fine dancer, Saint-Georges was also invited to balls and welcomed in the salons (and boudoirs) of highborn ladies. "Partial for the music of liaisons where amour had real meaning... he loved and was loved."[23] Yet he continued to fence daily in the various salles of Paris. There he met the Angelos, father and son, fencing masters from London; the mysterious Chevalier d'Éon; and the teenage Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, all of whom would play a role in his future.

Late life

Saint-Georges’s later life was deeply affected by the revolution. Since his mother was a black slave, Saint-Georges was deprived of the privileges enjoyed by whites in pre-Revolutionary France. On August 26, 1789, when the revolution declared equal rights to all French people, Saint-Georges embraced the new law and decided to provide services to the Revolutionary Army. In June 1791, the Parliament recruited volunteers from the entire French National Guard. Saint-Georges was the first person to sign in Lille. He still participated in music events when he was free.

In 1792, the Parliament established a light army consisting of colored people. The name of it was "Légion franche de cavalerie des Américains et du Midi", but it was later often referred to as "Légion St-Georges" because of the outstanding performance of Colonel Saint-Georges. In the early 1790s, due to the little effect Legion had, St. George was condemned by critics for being involved in non-revolutionary activities such as music events, and was dismissed and imprisoned for 18 months. Despite the support given by his soldiers and lower-level cadres, he was released but did not resume command after the appeal and was banned from dealing with his former comrades. Saint-Georges returned to St Domingue for a while. However, there was a fierce civil war between the revolutionaries and the old school. St. George was very disappointed with St-Domingue and returned to France. In 1797, he tried to join the army again and signed his petition "George". St. George wrote:

"I continue to show loyalty to the revolution. Since the beginning of the war, I have been serving with relentless enthusiasm, but the persecution I suffered has not diminished. I have no other resources, only to restore my original position."[24] However, his application failed again.

On June 12, 1799, Saint-Georges died of bladder disease.

Musical life and career

Nothing is known about Saint-Georges’s early musical training. Given his prodigious technique as an adult, Saint-Georges must have practiced the violin seriously as a child. There has been no documentation found of him as a musician before 1764, when violinist Antonio Lolli composed two concertos, Op. 2, for him,[note 1] and 1766, when composer François Gossec dedicated a set of six string trios, Op. 9,[26] to Saint Georges. Lolli may have worked with Bologne on his violin technique and Gossec on compositions.

(Beauvoir's novel says that "Platon", a fictional whip-toting slave commander on Saint-Domingue, "taught little Saint-Georges" the violin.[note 2])

Historians have discounted François-Joseph Fétis’ claim that Saint-Georges studied violin with Jean-Marie Leclair. Some of his technique was said to reveal influence by Pierre Gaviniès. Other composers who later dedicated works to Saint-Georges were Carl Stamitz in 1770,[28] and Avolio in 1778.[29]

In 1769, the Parisian public was amazed to see Saint-Georges, the great fencer, playing as a violinist in Gossec’s new orchestra, Le Concert des Amateurs. Four years later he became its concertmaster/conductor.[30] In 1772 Saint-Georges created a sensation with his debut as a soloist, playing his first two violin concertos, Op. II, with Gossec conducting the orchestra. "These concertos were performed last winter at a concert of the Amateurs by the author himself, who received great applause as much for their performance as for their composition."[31] According to another source, "The celebrated Saint-Georges, mulatto fencer [and] violinist, created a sensation in Paris ... [when] two years later ... at the Concert Spirituel, he was appreciated not as much for his compositions as for his performances, enrapturing especially the feminine members of his audience."[32]

Saint-Georges' first compositions, Op. I, were a set of six string quartets, among the first in France, published by famed French publisher, composer, and teacher Antoine Bailleux.[33] They were inspired by Haydn's earliest quartets, brought from Vienna by Baron Bagge. Saint-Georges wrote two more sets of six string quartets, three forte-piano and violin sonatas, a sonata for harp and flute, and six violin duos. The music for three other known compositions were lost: a cello sonata, performed in Lille in 1792, a concerto for clarinet, and one for bassoon.

Saint-Georges wrote twelve additional violin concertos, two symphonies, and eight symphonie-concertantes, a new, intrinsically Parisian genre of which he was one of the chief exponents. He wrote his instrumental works over a short span of time, and they were published between 1771 and 1779. He also wrote six opéras comiques and a number of songs in manuscript.

In 1773, when Gossec took over the direction of the prestigious Concert Spirituel, he designated Saint-Georges as his successor as director of the Concert des Amateurs. After fewer than two years under the younger man's direction, the group was described as "Performing with great precision and delicate nuances [and] became the best orchestra for symphonies in Paris, and perhaps in all of Europe."[34][35][note 3]

In 1781, Saint Georges’s Concert des Amateurs had to be disbanded due to a lack of funding. Playwright and Secret du Roi spy Pierre Caron de Beumarchais began to collect funds from private contributors, including many of the Concert's patrons, to send materiel aid for the American cause. The plan to send military aid via a fleet of fifty vessels and have those vessels return with American rice, cotton, or tobacco ended up bankrupting the French contributors as the American congress failed to acknowledge its debt and the ships were sent back empty.[36] Saint-Georges turned to his friend and admirer, Philippe D’Orléans, duc de Chartres, for help. In 1773 at the age of 26, Philippe had been elected Grand Master of the 'Grand Orient de France' after uniting all the Masonic organizations in France. Responding to Saint-Georges’s plea, Philippe revived the orchestra as part of the Loge Olympique, an exclusive Freemason Lodge.[37]

Renamed Le Concert Olympique, with practically the same personnel, it performed in the grand salon of the Palais Royal.[38] In 1785, Count D’Ogny, grandmaster of the Lodge and a member of its cello section, authorized Saint-Georges to commission Haydn to compose six new symphonies for the Concert Olympique. Conducted by Saint-Georges, Haydn’s "Paris" symphonies were first performed at the Salle des Gardes-Suisses of the Tuileries, a much larger hall, in order to accommodate the huge public demand to hear Haydn’s new works.[39] Queen Marie Antoinette attended some of Saint-Georges' concerts at the Palais de Soubise, arriving sometimes without notice, so the orchestra wore court attire for all its performances.[16] "Dressed in rich velvet or damask with gold or silver braid and fine lace on their cuffs and collars and with their parade swords and plumed hats placed next to them on their benches, the combined effect was as pleasing to the eye as it was flattering to the ear."[40] Saint-Georges played all his violin concertos as soloist with his orchestra.

Operas

.jpg)

In 1776 the Académie royale de musique, the Paris Opéra, was struggling financially and artistically. Saint-Georges was proposed as the next director of the opera. As creator of the first disciplined French orchestra since Lully, he was the obvious choice. But, according to Baron von Grimm's Correspondance Litteraire, Philosophique et Critique, three of the Opéra's leading ladies "... presented a placet (petition) to the Queen [Marie Antoinette] assuring her Majesty that their honor and delicate conscience could never allow them to submit to the orders of a mulatto."[35]

To keep the affair from embarrassing the queen, Saint-Georges withdrew his name from consideration. Meanwhile, to defuse the brewing scandal, Louis XVI took the Opéra back from the city of Paris - ceded to it by Louis XIV a century before - to be managed by his Intendant of Light Entertainments. Following the "affair", Marie-Antoinette preferred to hold her musicales in the salon of her petit appartement de la reine in Versailles. She limited the audience to her intimate circle and a few musicians, among them the Chevalier de Saint-Georges. "Invited to play music with the queen,"[41] Saint-Georges probably played his violin sonatas, with her Majesty playing the forte-piano.

The singers' placet may have ended Saint-Georges’ aspirations to higher positions as a musician. But, over the next two years, he published two more violin concertos and a pair of his Symphonies concertantes. Thereafter, except for his final set of quartets (Op. 14, 1785), Saint-Georges abandoned composing instrumental music in favor of opera.

Ernestine, Saint-Georges’s first opera, with a libretto by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, future author of Les Liaisons dangereuses, was performed on July 19, 1777, at the Comédie-Italienne. It did not survive its premiere. The critics liked the music, but panned the weak libretto, which was then usually given precedence over the music.[42] The Queen attended with her entourage. She came to support Saint-Georges’s opera but, after the audience kept echoing a character cracking his whip and crying "Ohé, Ohé," the Queen gave it the coup de grace by calling to her driver: "to Versailles, Ohé!"[43]

After the failure of the opera, the Marquise de Montesson, morganatic wife of the Duc d'Orléans, realized her ambition to engage Saint-Georges as music director of her fashionable private theater. He was glad to gain a position that entitled him to an apartment in the ducal mansion on the Chaussée d’Antin. After Mozart's mother died in Paris, the composer was allowed to stay at the mansion for a period with Melchior Grimm, who, as personal secretary of the Duke, lived in the mansion. The fact that Mozart lived for more than two months under the same roof with Saint-Georges, confirms that they knew each other.[46] The Duc d'Orléans appointed Saint-Georges as Lieutenant de la chasse of his vast hunting grounds at Raincy, with an additional salary of 2000 Livres a year. "Saint-Georges the mulatto so strong, so adroit, was one of the hunters..."[47]

Saint-Georges wrote and rehearsed his second opera, appropriately named La Chasse at Raincy. At its premiere in the Théâtre Italien, "The public received the work with loud applause. Vastly superior compared with ‘Ernestine’ ... there is every reason to encourage him to continue [writing operas]."[48] La Chasse was performed at her Majesty’s request at the royal chateau at Marly.[49] Saint-Georges’ most successful opéra comique was L’Amant anonyme, with a libretto based on a play by Mme de Genlis.[note 4][note 5]

In 1785, the Duke of Orléans died. The Marquise de Montesson, his morganatic wife, having been forbidden by the king to mourn him, shuttered their mansion, closed her theater, and retired to a convent near Paris. With his patrons gone, Saint-Georges lost not only his positions, but also his apartment. His friend, Philippe, now Duke of Orléans, presented him with a small flat in the Palais Royal. Living in the Palais, Saint-Georges was drawn into the whirlpool of political activity around Philippe, the new leader of the Orléanist party, the main opposition to the absolute monarchy.

As a strong Anglophile, Philippe, who visited England frequently, formed a close friendship with George, Prince of Wales. Due to the recurring mental illness of King George III, the prince was expected soon to become Regent. While Philippe admired Britain’s parliamentary system, Jacques Pierre Brissot de Warville, his chief of staff, envisioned France as a constitutional monarchy, on the way towards a republic. With Philippe as France's "Lieutenant-general", he promoted him as the sole alternative to a bloody revolution.

Meanwhile the duke’s ambitious plans for re-constructing the Palais-Royal left the Orchestre Olympique without a home and Saint-Georges unemployed. Seeing his protégé at loose ends and recalling that the Prince of Wales often expressed a wish to meet the legendary fencer, Philippe approved Brissot’s plan to dispatch Saint-Georges to London. He believed it was a way to ensure the Regent-in-waiting’s support of Philippe as future "Regent" of France. But Brissot had a secret agenda as well. He considered Saint-Georges, a "man of color", the ideal person to contact his fellow abolitionists in London and ask their advice about Brissot's plans for Les Amis des Noirs (Friends of the Blacks) modeled on the English anti-slavery movement.[50]

London and Lille

In London, Saint-Georges stayed with fencing masters Domenico Angelo and Henry, his son, whom he knew as an apprentice from early years in Paris. They arranged exhibition matches for him, including one at Carlton House, before the Prince of Wales.[51] After sparring with him, carte and tierce, the prince matched Saint-Georges with several renowned masters. One included La Chevalière D’Éon, aged 59, in a voluminous black dress. A painting by Charles Jean Robineau, violinist-composer and painter, showed the Prince and his entourage watching "Mlle" D’Éon score a hit on Saint-Georges, giving rise to rumors that the Frenchman allowed it out of gallantry for a lady.[52] But, as Saint-Georges had fenced with dragoon Captain D’Eon in Paris, he probably was deferring to his age. Saint-Georges played one of his concertos at the Anacreontic Society.[53] He also delivered Brissot’s request to the abolitionists MPs William Wilberforce, John Wilkes, and the Reverend Thomas Clarkson. Before Saint-Georges left England, Mather Brown painted his portrait. Asked by Mrs Angelo if it was a true likeness, Saint-Georges replied, "Alas, Madame it is frightfully so."[54]

Back in Paris, he completed and produced his latest opéra comique, La Fille Garçon, at the Théâtre des Italiens. The critics found the libretto wanting. "The piece, [was] sustained only by the music of Monsieur de Saint Georges.... The success he obtained should serve as encouragement to continue enriching this theatre with his productions."[55]

Saint-Georges found Paris full of pre-revolutionary fervor, less than a year before the great conflagration. Meanwhile, having nearly completed reconstruction of the Palais, Philippe had opened several new theaters. The smallest was the Théâtre Beaujolais, a marionette theater for children, named after his youngest son, the duc de Beaujolais. The lead singers of the Opéra provided the voices for the puppets. Saint-Georges wrote the music of Le Marchand de Marrons (The Chestnut Vendor) for this theater, with a libretto by Mme. De Genlis, Philippe's former mistress and then confidential adviser.

While Saint-Georges was away, the Concert Olympique had resumed performing at the Hôtel de Soubise, the old hall of the Amateurs. The Italian violinist Jean-Baptiste Viotti had been appointed as conductor.[40] Disenchanted, Saint-George, together with the talented young singer Louise Fusil, and his friend, the horn virtuoso Lamothe, embarked on a brief concert tour in the North of France. On May 5, 1789, the opening day of the fateful Estates General, Saint-Georges, seated in the gallery with Laclos, heard Jacques Necker, Louis XVI’s Minister of finance, saying, "The slave trade is a barbarous practice and must be eliminated."

Choderlos de Laclos, who replaced Brissot as Philippe’s chief of staff, intensified Brissot’s campaign to promote Philippe as an alternative to the monarchy. Concerned by its success, Louis dispatched Philippe on a bogus mission to London. On July 14, 1789, the fall of the Bastille took place, starting the Revolution, and Philippe, Duke of Orléans, missed his chance to save the monarchy.

Saint-Georges, sent ahead to London by Laclos, stayed at Grenier’s. This hotel in Jermyn Street became patronised by French refugees. Saint-Georges was entertaining himself lavishly.[56] Without salaries, he must have depended on Philippe. His assignment was to stay close to the Prince of Wales. As soon as Saint-Georges arrived, the Prince took the composer to his Marine Pavilion in Brighton. He also took him fox hunting and to the races at Newmarket. But when Philippe arrived, he became the Prince's regular companion. Saint-Georges was relieved to be free of the Prince.[57]

A cartoon captioned "St. George & the Dragon", with the dragon symbolizing the slave trade, appeared in the Morning Post on April 12, 1789. On his previous trip to London, when Saint-Georges passed Brissot’s request to the British abolitionists, they complied by translating their literature into French for his fledgling Société des amis des Noirs. Saint-Georges met with them again, this time on his own account. "Early in July, walking home from Greenwich, a man armed with a pistol demanded his purse. The Chevalier disarmed the man... but when four more rogues hidden until then attacked him, he put them all out of commission. M. de Saint Georges received only some contusions which did not keep him from going on that night to play music in the company of friends."[58] The nature of the attack, with four attackers emerging after the first one made sure they had the right victim, appeared to be an assassination attempt disguised as a hold-up, arranged by the "Slave Trade" to put an end to his abolitionist activities.[59]

In late June, Philippe, dubbed "The Red Duke" in London, realized that his "mission" there was a ruse used by the French king to get him out of the country. He amused himself with the Prince, horse racing, young women and champagne.[60] Philippe clung to a vague promise made by King Louis to make him Regent of the Southern Netherlands. But the Belgians wanted a Republic, and rejected Philippe. Saint-Georges headed back to France.

"On Thursday, July 8, 1790, in Lille’s municipal ballroom, the famous Saint-Georges was the principal antagonist in a brilliant fencing tournament. Though ill, he fought with that grace which is his trademark. Lightning is no faster than his arms and in spite of running a fever, he demonstrated astonishing vigor."[61] Two days later looking worse but in need of funds, he offered another assault, this one for the officers of the garrison. But his illness proved so serious that it sent him to bed for six long weeks.[62] The diagnosis according to medical science at the time was "brain fever" (probably meningitis). Unconscious for days, he was taken in and nursed by some kind citizens of Lille. While still bedridden, deeply grateful to the people who were caring for him, Saint-Georges began to compose an opera for Lille’s theater company. Calling it Guillome tout Coeur, ou les amis du village, he dedicated it to the citizens of Lille. "Guillaume is an opera in one act. ...The music by Saint-George is full of sweet warmth of motion and spirit...Its [individual] pieces distinguished by their melodic lines and the vigor of their harmony. The public...made the hall resound with its justly reserved applause."[62] It was to be his last opera, lost, including its libretto.

Louise Fusil, who had idolized Saint-Georges since she was a girl of 15, wrote: "In 1791, I stopped in Amiens where St. Georges and Lamothe were waiting for me, committed to give some concerts over the Easter holidays. We were to repeat them in Tournai. But the French refugees assembled in that town just across the border, could not abide the Créole they believed to be an agent of the despised Duke of Orléans. St. Georges was even advised [by its commandant] not to stop there for long."[63] According to a report by a local newspaper: "The dining room of the hotel where St. Georges, a citizen of France, was also staying, refused to serve him, but he remained perfectly calm; remarkable for a man with his means to defend himself."[64]

Louise describes the scenario of Saint-Georges's "Love and Death of the Poor Little Bird", a programmatic piece for violin alone, which he was constantly entreated to play especially by the ladies. Its three parts depicted the little bird greeting the spring; passionately pursuing the object of his love, who alas, has chosen another; its voice grows weaker then, after the last sigh, it is stilled forever. This kind of program music or sound painting of scenarios such as love scenes, tempests, or battles complete with cannonades and the cries of the wounded, conveyed by a lone violin, was by that time nearly forgotten. Saint-Georges must have had fun inventing it as he went along. Louise places his improvisational style on a par with her subsequent musical idol, Hector Berlioz: "We did not know then this expressive ...depiction a dramatic scene, which Mr. Berlioz later revealed to us... making us feel an emotion that identifies us with the subject." Curiously, some of Saint-Georges’s biographers are still looking for its score, but Louise’s account leaves no doubt that it belonged to the lost art of spontaneous improvisation.[65][66]

Tired of politics yet faithful to his ideals, St. Georges decided to serve the Revolution, directly. With 50,000 Austrian troops massed on its borders, the first citizen’s army in modern history was calling for volunteers. In 1790, having recovered from his illness, Saint-George was one of the first in Lille to join its Garde Nationale.[note 6] But not even his military duties in the Garde Nationale could prevent St. Georges from giving concerts. Once again he was building an orchestra which, according to the announcement in the paper, "Will give a concert every week until Easter."[67] At the conclusion of the last concert, the mayor of Lille placed a crown of laurels on St. Georges’ brow and read a poem dedicated to him.[68]

On April 20, 1792, compelled by the National Assembly, Louis XVI declared war against his brother-in-law, Francis II.[69] General Dillon, commander of Lille, was ordered by Dumouriez to attack Tournai, reportedly only lightly defended. Instead, massive fire by the Austrian artillery turned an orderly retreat into a rout by the regular cavalry but not that of the volunteers of the National Guard.[70] Captain St. Georges, promoted in 1791,[71] commanded the company of volunteers that held the line at Baisieux.[note 7] A month later, "M. St. Georges took charge of the music for a solemn requiem held [in Lille] for the souls of those who perished for their city on the fateful day of April 29."[72]

Légion St.-Georges

On September 7, 1792, Julien Raimond, leader of a delegation of free men of color from Saint-Domingue (Haiti), petitioned the National Assembly to authorize the formation of a Legion of volunteers, so "We too may spill our blood for the defense of the motherland." The next day, the Assembly authorized the formation of a cavalry brigade of "men of color", to be called Légion nationale des Américains & du midi,[note 8] and appointed Citizen St. Georges colonel of the new regiment.[note 9][73] St. Georges’ Légion, the first all colored regiment in Europe, "grew rapidly as volunteers [attracted by his name] flocked to it from all over France."[74]

Among its officers was Thomas Alexandre Dumas, the novelist’s father, one of St. Georges’s two lieutenant colonels.[71] Colonel St. Georges found it difficult to obtain the funds allocated to his unit towards equipment and horses badly needed by his regiment. With a number of green recruits still on foot, it took his Legion three days to reach its training camp in Laon. In February, when Pache,[note 10] the minister of war, ordered St. Georges to take his regiment to Lille and hence to the front, he protested that, "Short of horses, equipment and officers, I cannot lead my men to be slaughtered ...without a chance to teach them to tell their left from their right."[75]

That May, Citizen Maillard denounced St. Georges’ Legion to the Committee of Public Safety, for enrolling individuals suspected of royalist sentiments; he did not mention their being "men of color".[76] Meanwhile Commissaire Dufrenne, one of Pache’s henchmen, accused St. Georges as: "A man to watch; riddled by debts he had been paid I think 300,000 livres to equip his regiment; he used most of it I am convinced to pay his debts; with a penchant for luxury he keeps, they say, 30 horses in his stables, some of them worth 3000 livres; what horror..."[77] Though Dufrenne’s accusations were based on mere hearsay, Saint Georges was called to Paris where, promptly established by the Committee of Public Safety that Pache never sent his regiment any funds,[note 11] St. Georges was cleared of all charges and re-confirmed as Colonel of his Legion.

Meanwhile the legion's colonel had other grievances. On his return to Lille to rejoin his regiment on its way to the front, he found most of his black troopers and some of his officers gone. It must have been a bitter moment when he realized that without them his legion had lost its raison d’être. Moreover, War Minister Pache, instead of sending him supplies and officers, decreed leaving for the front, the Légion St. Georges would be renamed le 13e regiment de chasseurs à cheval, and attached to the army of Belgium. Some of its men of color were ordered to embark for the West Indies "to defend our possessions in America".[78] Only the Legion’s first company, still called l’Américaine, retained some of Saint Georges’ original staff: Lieutenant Colonels Champreux and Dumas, and Captains Duhamel and Colin, along with seventy-three of his old troopers. With Lille virtually on the front lines, while patrolling in enemy territory,"Citizen Saint-Georges, was seen by some of his comrades standing up to the enemy with only fifty of his chasseurs and taking command of a passing column, on his own volition, purely for the pleasure of serving the Republic."[79]

On January 21, 1793, Louis Capet, the former King Louis XVI, was found guilty of treason and guillotined on the Place de la Révolution (today's Place de la Concorde). General Dumouriez, who became minister of war after Pache was removed for corruption, took charge of the army of the North. Dumouriez, a Girondist, on the moderate side of the Revolution, spoke out too freely against the Jacobins of the Convention for executing the king. As a result, though revered as the hero of the French victories at Valmy and Jemappes, the National Convention ordered his arrest. Failing to dislodge him from the front, they sent a delegation led by Beurnonville, the new minister of war, to Dumouriez’s headquarters to bring him back to Paris. Colonel St. Georges was ordered to take a hundred of his chasseurs and escort the delegation from Lille to Dumouriez’s headquarters in St. Amand. On reaching the village of Orchies, claiming that the horses were fatigued after six leagues at a gallop, St. Georges asked the delegation to take another escort for the rest of the way. It is possible that, told of the purpose of the mission, he preferred not to be part of it. The delegation continued on with an escort provided by General Joseph de Miaczinsky, commander at Orchies.

Next morning at breakfast, a courier from Dumouriez arrived with a note for Miaczinsky. After reading the message, the General showed it to St. Georges and his officers. According to the note, Dumouriez, having arrested the delegation, was ordering Miaczinsky to take Lille with his division and join him in his march on Paris to "uphold the ‘will of the army,’ to reinstate the constitution of ’91 and to save the Queen."[80] When Miaczinsky asked St. Georges to assist him on his march on Lille, St. Georges refused, saying that "being under orders to his commander, General Duval, nothing on earth could force me to fail in my duties."[81] This was the moment when Saint-Georges, the son of a slave, chose the Revolution over his doomed Queen and the society that nurtured him. Accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel Dumas and Captain Colin, he took off at a gallop to warn Lille of the looming danger. Having warned the garrison in time, when Miaczinsky arrived he was arrested by Duval.[82] Taken to Paris he was tried, found guilty and guillotined. General Dumouriez, his plans thwarted by "the famous mulatto Saint-Georges, colonel of a regiment of hussars..."[80] together with Louis-Philippe, son of the Duke of Orléans and future king of France, defected to the Austrians.

In spite of the continuing shortages of officers and equipment, Saint-George’s regiment distinguished itself in the Netherlands campaign. But at the siege of Bergen op Zoom, their Colonel could not take part in the action. On September 25 St. Georges and ten of his officers were arrested and taken away. After two weeks, his officers were released, but St. Georges remained in prison.

Early that September, Maréchal Bécourt, commandant of Lille, wrote to inform the Ministry of War, that "The 13th regiment of Chasseurs, formerly called Légion St. Georges, has arrived here in great penury due to the laxity of its leader. That is the report of Lieutenant Colonel Dumas..."[83] Ten days before the arrest of Colonel St. Georges and his officers, Dumas, skipping a rank, was promoted to Brigadier General. One day later, skipping yet another rank, writing his superiors: “ ...leaving for the army of the Pyrenées, I must have real Revolutionaries to work with against the enemies of our liberty..." he signed himself, "Dumas, Le General de Division."[84] Alas, Thomas Alexandre Dumas earned his spectacular rises in rank as Commissaire of General Security and Surveillance of the Committee of Public Safety.

Under the new Law of Suspects, St. Georges was incarcerated without charge in the fortress of Hondainville-en-Oise for 13 months. During his incarceration, France was in the midst of the Terror. On October 12, 1793 the Queen was guillotined on Place de la Republique; Brissot and 22 of his fellow Girondins, mounted the scaffold on October 31 and Philippe Orléans, obliged to call himself Égalité, followed them on November 5. With Danton riding in a tumbril to the scaffold, the Terror began to devour its own. The number of executions including those of ordinary citizens swelled to 26 a day. Paris grew weary of the killing and, as the successes of the army had relieved the public of the threat of invasion used by Robespierre to maintain the Terror, on July 28 the National Convention shook off its fear and sent Robespierre and 21 of his cohorts to the guillotine. St. Georges, living under the threat of execution, was spared only because Commissaire Sylvain Lejeune of Hondainvile and the district of Oise gave bloodthirsty speeches, but kept his guillotine under wraps. Three more months went by before the Committee of General Security ordered Colonel St. Georges, never charged with any wrongdoing, released from prison.[85]

His former world in Paris a thing of the past, St. Georges had only one compelling ambition: to regain his rank and his regiment. It took six months of cooling his heels at the Ministry of War, while living on an inactive officer’s half-pay, for the army to re-instate him as colonel of his regiment. In theory. In practice he found that while he was in prison his regiment had acquired, not one, but two colonels. One of them, Colonel Target, offered to cede his post to "the founder of the regiment", but the other one, Colonel Bouquet, vowed to fight St. Georges tooth and claw. After a long and arduous year spent between hope and despair fighting to keep his post, on October 30, 1795, invoking an obscure law,[note 12] Bouquet won his case. Saint-Georges was dismissed from the army and ordered to leave his regiment. In addition he was ordered to retire to any community save the one where the regiment might be located. Thus ended Saint Georges’ military career, with nothing, not even a cheap medal, to show for his travails.

Saint-Domingue

In Saint-Domingue, the news from abroad that the "whites of La France had risen up and killed their masters", spread among the black slaves of the island. "The rebellion was extremely violent...the rich plain of the North was reduced to ruins and ashes..."[86] After months of arson and murder, Toussaint Louverture, a Haitian revolutionary, took charge of the slave revolt. In the Spring of 1796, a commission with 15,000 troops and tons of arms sailed for Saint-Domingue to abolish slavery. Second to Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, leader of the commission, was Julien Raimond, the founder of Saint-Georges’ Légion.

According to Louise Fusil, Saint Georges and his friend Lamothe had been absent from Paris for nearly two years. "I since learned that they had left for Saint-Domingue, then in full revolt; it was rumored they had been hung in a mutiny. I gave them up for dead and mourned them with all my heart, when one day, as I sat in the Palais Royal with a friend absorbed in a magazine... I looked up and screamed, thinking I saw ghosts. They were Lamothe and Saint Georges who, clowning, sang to me ‘At last there you are! You thought we’ve been hung /For almost two years what became of you?’ 'No, I was not sure that you were hung, but I did take you for ghosts, come back to haunt me!' 'We nearly are [ghosts] they answered, for we come from very far indeed.'"[87]

It stands to reason that Julien Raimond would want to take St. Georges, an experienced officer, with him to Saint-Domingue, then in the throes of a bloody civil war. While we lack concrete evidence that St. Georges was aboard the convoy of the commission, the fact that we find Captain Colin, and Lamotte (Lamothe) on the payroll of a ship of the convoy to Saint-Domingue, confirms Louise Fusil’s account. So does Lionel de La Laurencie's statement: "The expedition to Saint-Domingue was Saint-Georges’ last voyage," adding that "Disenchantment and melancholy resulting from his experiences during that voyage must have weighed heavily on his aging shoulders"[88] In the end, disheartened by the savagery of the strife between blacks and mulattoes, St. Georges and Lamothe were fortunate to escape from the island with their lives.

Within a fortnight of returning from that harrowing journey, St. Georges was again building a symphony orchestra. Like his last ensemble, Le Cercle de l’Harmonie was also part of a Masonic lodge performing in what was formerly the Palais Royal. The founders of the new Loge, a group of nouveau riche gentlemen bent on re-creating the elegance of the old Loge Olympique, were delighted to find St. Georges back in Paris. According to Le Mercure Français, "The concerts...under the direction of the famous Saint Georges, left nothing to be desired as to the choice of pieces or the superiority of their execution."[89] Though a number of his biographers maintain that at the end of his life, St. Georges lived in abject poverty, the Cercle was not exactly the lower depths. Rejected by the army, St. Georges, at the age of 51, found solace in his music. Sounding like any veteran performer proud of his longevity, he said: "Towards the end of my life, I was particularly devoted to my violin," adding: "never before did I play it so well!"[90]

In the late spring of 1799, there came bad news from Saint-Domingue: Generals Hédouville and Roume, the Directoire’s emissaries, reverting to the discredited policy of stirring up trouble between blacks and mulattoes, succeeded in starting a war between pro-French André Rigaud's mulattoes, and separatist Toussaint Louverture’s blacks. It was so savage that it became known as the "War of Knives." Hearing of it affected St. Georges, already suffering from a painful condition which he refused to acknowledge. Two of his contemporary obituaries reveal the course of his illness and death.

La Boëssière fils: "Saint-Georges felt the onset of a disease of the bladder and, given his usual negligence, paid it little attention; he even kept secret an ulcer, source of his illness; gangrene set in and he succumbed on June 12, 1799.[note 13]

J. S. A. Cuvelier in his NECROLOGY: "...For some time he had been tormented by a violent fever...his vigorous nature had repeatedly fought off this cruel illness; [but] after a month of suffering, the end came on 21 Prairial [June 9] at five o’clock in the evening. Some time before the end, St. Georges stayed with a friend [Captain Duhamel] in the rue Boucherat. His death was marked by the calm of the wise and the dignity of the strong."[92]

Saint-Georges’s death certificate was lost in a fire; what remains is only a report by the men who removed his body: "St. Georges Bologne, Joseph, rue Boucherat No. 13, Bachelor, 22 Prairial year 7, Nicholas Duhamel, Ex-officer, same house, former domicile rue de Chartres, taken away by Chagneau." Above the name "Joseph" someone, no doubt the "receiver", scribbled "60 years", merely an estimate which, mistaken for a death certificate, added to the confusion about Saint-Georges’s birth-year. Since he was born in December 1745, he was only 53.2006

Nicholas Duhamel, the ex-officer mentioned in the report of the "receivers", a Captain in St. Georges’ Legion, was his loyal friend until his death. Concerned about his old colonel's condition, he stopped by his apartment on rue de Chartres in the Palais Royal and, having found him dying, took him to his flat in rue Boucherat where he took care of him until the end.

This year died, twenty-four days apart, two extraordinary

but very different men, Beaumarchais and Saint-Georges;

both Masters at sparring; the one who could be touched by a

foil, was not the one who was more enviable for his virtues.

— Charles Maurice (1799)

Works

Operas

- Ernestine, opéra comique in 3 acts, libretto by Choderlos de Laclos revised by Desfontaines, première in Paris, Comédie Italienne, July 19, 1777, lost. Note: a few numbers survive.

- La Partie de chasse, opéra comique in 3 acts, libretto by Desfontaines, public premiere in Paris, Comédie Italienne, October 12, 1778, lost. Note: a few numbers survive.

- L'Amant anonyme, comédie mélée d'ariettes et de ballets, in 2 acts, after a play by Mme. de Genlis, première in Paris, Théâtre de Mme. de Montesson, March 8, 1780, complete manuscript in Paris Bibliothèque Nationale, section musique, côte 4076.

- La Fille garçon, opéra comique mélée d'ariettes in 2 acts, libretto by Desmaillot, premiere in Paris, Comédie Italienne, August 18, 1787, lost.

- Aline et Dupré, ou le marchand de marrons, children's opera, premiere in le Théâtre du comte de Beaujolais, 1788. lost.

- Guillaume tout coeur ou les amis du village, opéra comique in one act, libretto by Monnet, première in Lille, September 8, 1790, lost.

Symphonies

- Deux Symphonies à plusieurs instruments, Op. XI, No. 1 in G and No. 2 in D.

Note: the latter is identical with the Overture to the opéra comique, "L'Amant Anonyme." The orchestration consists of strings, two oboes and two horns.

Concertante

Violin concertos

Saint-Georges composed 14 violin concertos. Before copyrights, several publishers issued his concertos with both Opus numbers and numbering them according to the order in which they were composed. The thematic incipits on the right, should clear up the resulting confusion.

- Op. II, No. 1 in G and No. 2 in D, published by Bailleux, 1773

- Op. III, No. 1 in D and No. 2 in C, Bailleux, 1774

- Op. IV, No. 1 in D and No. 2 in D, Bailleux, 1774 (No. 1 also published as "Op. post." while No. 2 is also known simply as "op. 4")

- Op. V, No.1 in C and No. 2 in A, Bailleux, 1775

- Op. VII, No. 1 in A and No. 2 in B flat, Bailleux, 1777

- Op. VIII, No. 1 in D and No. 2 in G, Bailleux n/d (No. 2 issued by Sieber, LeDuc and Henry as No. 9. No. 1 is also known simply as "op. 8")

- Op. XII, No. 1 in Eb and No. 2 in G, Bailleux 1777 (both issued by Sieber as No. 10 and No. 11)

Symphonies concertantes

- Op. VI, No. 1 in C and No. 2 in B flat, Bailleux, 1775

- Op. IX, No. 1 in C and No. 2 in A, LeDuc, 1777

- Op. X, for two violins and viola, No. 1 in F and No. 2 in A, La Chevardière, 1778

- Op. XIII, No. 1 in E flat and No. 2 in G, Sieber, 1778

Unlike the concertos, their publishers issued the symphonie-concertantes following Bailleux's original opus numbers, as shown by the incipits on the right.

Chamber music

Sonatas

- Trois Sonates for keyboard with violin: B flat, A, and G minor, Op. 1a, composed c. 1770, published in 1781 by LeDuc.

- Sonata for harp with flute obligato, n.d.: E flat, original MS in Bibliothèque Nationale, côte: Vm7/6118

- 'Sonate de clavecin avec violin obligé G major, arrangement of Saint-Georges's violin concerto Op. II No. 1 in G, in the collection "Choix de musique du duc regnant des Deux-Ponts."

- Six Sonatas for violin accompanied by a second violin: B flat, E flat, A, G, B flat, A: Op. posth. Pleyel, 1800.

- Cello Sonata, lost, mentioned by a review in the Gazette du departement du Nord on April 10, 1792.

String quartet

- Six quatuors à cordes, pour 2 vls, alto & basse, dédiés au prince de Robecq, in C, E flat, G minor, C minor, G minor, & D. Op. 1; probably composed in 1770 or 1771, published by Sieber in 1773.

- Six quartetto concertans "Aux gout du jour", no opus number. In B flat, G minor, C, F, G, & B flat, published by Durieu in 1779.

- Six Quatuors concertans, oeuvre XIV, in D, B flat, F minor, G, E flat, & G minor, published by Boyer, 1785.

Vocal music

'Recueil d'airs et duos avec orchestre: stamped Conservatoire de musique #4077, now in the music collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale, contains:

- Allegro: Loin du soleil, in E flat.

- Andante: N'êtes vous plus la tendre amie? in F.

- Ariette: Satisfait du plaisir d'aimer; in A.

- Ariette-Andante: (Clemengis) La seule Ernestine qui m'enflamme; in E flat

- Duo: (Isabelle & Dorval) C'est donc ainsi qu'on me soupconne; in F.

- Scena-Recitavo: Ernestine, que vas tu faire .. as tu bien consulte ton Coeur? in E flat.

- Aria: O Clemengis, lis dans mon Ame; in C minor.

- Air: Image cherie, Escrits si touchants; in B flat.

- Air: Que me fait a moi la richesse...sans songer a Nicette; in F minor.

- Duo: Au prés de vous mon Coeur soupire

Note: The names of the characters, Ernestine and Clemengis, in numbers 4, 6, 7 and 8 of the above pieces indicate they came from the opera Ernestine; number 5 is probably from La Partie de chasse.

The orchestra for all the above consists of strings, two oboes and two horns.

Additional songs

- Air: "Il n'est point, disoit mon père,"Air de l'Opéra Ernestine, in Journal de Paris 1777.

- Two Airs de la Chasse, Mathurin dessus l'herbette and Soir et matin sous la fougère "de M. de Saint-Georges" in Journal de La Harpe, of 1779, the first Air, No. 9, the second one, No. 10, dated 1781, marked: "With accompagnement by M. Hartman," clearly only the voice part may be considered to be by Saint-Georges. The same is true of an Air "de M. de St.-George", L'Autre jour sous l'ombrage, also in the Journal de La Harpe (8e Année, No. 7), marked: "avec accompagnement par M. Delaplanque."

- Two Italian Canzonettas: "Sul margine d'un rio" and "Mamma mia" (different than the spurious "Six Italian Canzonettas") copied by an unknown hand (including the signature) but authenticated by a paraphe (initials) in Saint-Georges' hand. They are in BnF, ms 17411.

Dubious works

The opera, Le Droit de seigneur taken for a work by Saint-Georges is in fact by J-P. E. Martini: (one aria contributed by Saint-Georges, mentioned in 1784 by Mercure, is lost).

A Symphony in D by "Signor di Giorgio" in the British Library, arranged for pianoforte, as revealed by Prof. Dominique-René de Lerma is by the Earl of Kelly, using a nom de plume.

A quartet for harp and strings, ed. by Sieber, 1777, attributed to Saint-Georges, is mentioned in an advertisement in Mercure de France of September 1778 as: "arranged and dedicated to M. de Saint-Georges" by Delaplanque. This is obviously by the latter.

A Sonata in the Recueil Choix de musique in the Bibliothèque Nationale, is a transcription for forte-piano and violin of Saint-Georges' violin concerto in G major, Op. II, No.1. This is the only piece by Saint-Georges in the entire collection erroneously attributed to him.

Recueil d'Airs avec accompagnement de forte piano par M. de St. Georges pour Mme. La Comtesse de Vauban, sometimes presented as a collection of vocal pieces by Saint-Georges, contains too many numbers obviously composed by others. For example, Richard Coeur de lion is by Grétry; Iphigenie en Tauride is by Gluck; and an aria from Tarare is by Salieri. Even if Saint-Georges had arranged their orchestral accompaniments for forte-piano, it would be wrong to consider them as his compositions. As for the rest, though some might be by Saint-Georges, since this may only be resolved by a subjective stylistic evaluation, it would be incorrect to accept them all as his work.

Six Italian Canzonettas by a Signor di Giorgio, for voice, keyboard or harp, and "The Mona melodies:" a collection of ancient airs from the Isle of Man, in the British Library, are not by Saint-Georges.

Recueil de pieces pour forte piano et violon pour Mme. la comtesse de Vauban erroneously subtitled "Trios" (they are solos and duos), a collection of individual movements, some for piano alone, deserves the same doubts as the Recueil d'Airs pour Mme. Vauban. Apart from drafts for two of Saint-Georges' oeuvres de clavecin, too many of these pieces seem incompatible with the composer's style. Les Caquets (The Gossips) a violin piece enthusiastically mentioned by some authors as typical of Saint-Georges' style, was composed in 1936 by the violinist Henri Casadesus. He also forged a spurious Haendel viola concerto and the charming but equally spurious "Adelaide" concerto supposedly by the 10-year-old Mozart, which Casadesus himself later admitted having composed.

Discography

The following is a list of all known commercial recordings.

Symphonies concertantes

- Symphonie Concertante, Op. IX No. 1 in C: Miroslav Vilimec and Jiri Zilak, violins, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor, Avenira, 1996–98.

- Symphonie Concertante, Op. IX No. 2 in A: Miroslav Vilimec and Jiri Zilak, violins, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor, Avenira, 1996–98.

- Symphonie Concertante, Op. X No. 1 in F: Miroslav Vilimec and Jiri Zilak, violins, Jan Motlik, viola, Frantisek Preisler, conductor. Avenira, 1996–98.

- Symphonie Concertante, Op. X No. 2 in A: Miroslav Vilimec and Jiri Zilak, violins, Jan Motlik, viola, Frantisek Preisler, conductor. Avenira, 1996–98.

- Symphonie Concertante, Op. XII (sic) in Eb: Miroslav Vilimec and Jiri Zilak, violins, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor. Avenira, 1996–98.

- Symphonie Concertante, Op. XIII in G:

- Miriam Fried and Jamie Laredo, violins, London Symphony Orchestra, Paul Freeman conductor, Columbia Records, 1970.

- Vilimec and Ailak, violins, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Preisler conductor, Avenira 1996–98.

- Christopher Guiot and Laurent Philippe, violins, with Les Archets de Paris. ARCH, 2000.

- Micheline Blanchard and Germaine Raymond, violins, Ensemble Instrumental Jean-Marie Leclair, Jean-François Paillard, conductor, Erato.

- Huguette Fernandez and Ginette Carles, violins, Orchestre de Chambre Jean-François Paillard, Paillard, conductor, Musical Heritage Society.

- Malcolm Lathem and Martin Jones, violins, Concertante of St. James, London, Nicholas Jackson, conductor, RCA Victor, LBS-4945.

Symphonies

Symphony Op. XI No. 1 in G:

- ‘’Orchestre de chambre de Versailles’’, Fernard Wahl, conductor, Arion, 1981.

- Tafelmusik orchestra, Jeanne Lamon violinist-conductor, Assai M, 2004.

- ‘’Le Parlement de musique’’, Martin Gester conductor, Assai M, 2004.

- ‘’Ensemble Instrumental Jean-Marie Leclair’’, Jean-François Paillard, conductor, Erato n.d. Contemporains Français de Mozart’’.

- London Symphony Orchestra, Paul Freeman, conductor, Columbia Records, 1974.

- L’ amant anonyme, overture in three movements:

- Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra, Jeanne Lamon, Conductor, Assai M, 2004

- L’ amant anonyme, contredanse:

- Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra, Jeanne Lamon, Conductor, Assai M, 2004

- L’ amant anonyme, Ballet No.1 and No. 6:

- Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra, Jeanne Lamon, Conductor, Assai M, 2004

Symphony Op. XI No. 2 in D:

- L’Ensemble Instrumental Jean-Marie Leclair, Jean-François Paillard, conductor. Erato, n.d. Contemporains Français de Mozart.

- Orchestre de chambre de Versailles, Bernard Wahl, conductor, Arion, 1981.

- Les Archets de Paris, Christopher Guiot conductor, Archets, 2000.

- Tafelmusik orchestra, Jeanne Lamon, violinist-conductor, Assai M, 2004.

- Le Parlement de musique, Martin Gester, conductor, Assai M, 2004.

Violin concertos

- Concerto Op. II, No. 1 in G:

- Miroslav Vilimec, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler conductor, Avenira, 2000.

- Concerto Op. II, No. 2 in D:

- Miroslav Vilimec, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor, Avenira, 2000.

- Stéphanie-Marie Degrand, Le Parlement de musique Gester, conductor, Assai, 2004.

- Yura Lee, Bayerische Kammerphilharmonie, Reinhard Goebel Conductor, OEHMS Classics, 2007

- Concerto Op. III, No. 1 in D:

- Jean-Jacques Kantorow, Orchestre de chambre Bernard Thomas, Arion, 1974.

- Miroslav Vilimec, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor, Avenira, 2000.

- Linda Melsted, Tafelmusik Orchestra, Jeanne Lamon, violinist-conductor, CBC Records, 2003.

- Qian Zhou, Toronto Camerata, Kevin Mallon, conductor, Naxos, 2004.

- Concerto Op. III, No. 2 in C:

- Tamás Major, Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana, Forlane, 1999.

- Miroslav Vilimec, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor, Avenira, 2000.

- Concerto Op. IV, No. 1 in D:

- Miroslav Vilimec, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor, Avenira 2000.

- Qian Zhou, Camerata Toronto, Kevin Mallon, conductor, Naxos, 2004. (The recording of this concerto was mistakenly reissued by Artaria as Op. posthumus, see incipit of concerto Op. IV, No. 1 in D, in "Works".)

- Concerto Op. IV, No. 2 in D:

- Hana Kotková, Orchestra della Svizzera Italiiana, Forlane, 1999.

- Concerto Op. V, No. 1 in C:

- Jean-Jacques Kantorow, Orchestre de chambre Bernard Thomas, Arion, 1974

- Miroslav Vilimec, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor, Avenira, 2000.

- Christoph Guiot, Les Archets de Paris, ARCH, 2000

- Takako Nishizaki, Köln Kammerorchester, Helmut Müller-Brühl, conductor, Naxos, 2001.

- Concerto Op. V No. 2 in A:

- Jean-Jacques Kantorow, Orchestre de chambre Bernard Thomas, Arion, 1974

- Rachel Barton, Encore Chamber Orchestra, Daniel Hegge, conductor, Cedille, 1997.

- Miroslav Vilimec, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor, Avenira, 2000.

- Takako Nishizaki, Köln Kammerorchester, Helmut Müller-Brühl, conductor, Naxos, 2001.

- Concerto Op. VII No. 1 in A: Anthony Flint, Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana, Forlane, 1999.

- Concerto Op. VII No. 2 in B flat:

- Miroslav Vilimec, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor, Avenira, 2000.

- Hans Liviabella, Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana Alain Lombard, conductor, Forlane, 1999.

- Concerto "Op. VII, No. 1" actually Op. XII, No. 1: in D: Anne–Claude Villars, L'Orchestre de chambre de Versailles, Bernard Wahl, conductor, Arion, 1981.

- concerto "Op. VII, No. 2" actually Op. XII No. 2 in G: Anne–Claude Villars, L'Orchestre de chambre de Versailles, Bernard Wahl, conductor, Arion, 1981.

- Concerto Op. VIII, No. 1 in D:

- Miroslav Vilimec, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor, Avenira, 2000.

- Concerto "Op. VIII, No. 9", actually Op. VIII, No. 2 in G:

- Jean-Jacques Kantorow, Orchestre de chambre Bernard Thomas, Arion, 1976, Koch, 1996.

- Takako Nishizaki, Köln Kammerorchester, Helmut Müller-Brühl, conductor, Naxos, 2001.

- Stéphanie-Marie Degand, Le Parlement de musique, Martin Gester, conductor, Assai M, 2004.

- Miroslav Vilimec, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor. Avenira, 2000.

- Concerto "Op. VIII, No. 10", actually Op. XII, No. 1 in D: Miroslav Vilimec, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor. Avenira, 2000.

- Concerto "Op. VIII, No. 11", actually Op. XII, No. 2 in G:

- Miroslav Vilimec, Pilsen Radio Orchestra, Frantisek Preisler, conductor. Avenira, 2000.

- Qian Zhou, Toronto Camerata, Kevin Mallon, conductor. Naxos 2004. (Listed as Concerto No. 10 in G in the recent Artaria Edition) The Largo of this recording is identical with that of Op. V, No. 2 in A.

(As mentioned above, a Concerto with Qian Zhou, reissued by Artaria as "Op. Posthumus in D" is the same as Op, IV No. 1.)

Chamber music

- String Quartets:

Six quartets Op. 1 (1771).

- Juilliard Quartet, Columbia Records, 1974.

- Antarés, B flat only Integral, 2003.

- Coleridge, AFKA, 1998.

- Jean-Noel Mollard, Arion 1995.

Six Quatuors Concertans, "Aux gôut de jour", no opus number (1779).

- Coleridge Quartet, AFKA, 2003.

- Antarés, Integral 2003.

Six Quartets Op. 14 (1785).

- Quatuor Apollon, Avenira, 2005.

- Joachim Quartet, Koch Schwann 1996.

- Quatuor Les Adieux, Auvidis Valois, 1996.

- Quatuor Atlantis, Assai, M 2004.

- Quatuor Apollon, Avenira, 2005

Three Keyboard and Violin Sonatas (Op. 1a):

- J.J. Kantorow, violin, Brigitte Haudebourg, Clavecin, Arion 1979.

- Stéphanie-Marie Degand, Violin, Alice Zylberach, piano, Assai M, 2004.

Miscellaneous

- Adagio in F minor, edited by de Lerma, performance notes by Natalie Hinderas, Orion, 1977.

- Air d’Ernestine: Faye Robinson, soprano, London Symphony Orchestra, Paul Freeman conductor, Columbia Records, 1970.

- Overture and two Airs of Leontine from L’Amant anonyme: Enfin, une foule importune: Du tendre amour: Odile Rhino, soprano, Les Archets de Paris, Christophe Guiot conductor, Archives Records, 2000.

- Excerpts from Ballets No. 1 & 2, and Contredance from L’Amant anonyme, Tafelmusik Orchestra, Jeanne Lamon, violinist-conductor, CBC Records, 2003.

Footnotes

Notes

- Lolli's dedication was to Joseph's father: "To M. de Bologne de Saint-Georges, who gave the arts a priceless gift in the person of his son."[25]

- Platon is, erroneously, mentioned as Saint-George’s first violin teacher by some of his serious biographers. But Saint-Georges did not go to Saint-Domingue until the age of 51.[27]

- Von Grimm comments that they really objected to Saint-Georges's reputation "as a taskmaster."

- She was a playwright, mistress of Philippe d’Orléans and governess of his children.

- L’Amant is Saint-Georges’s sole opera to be found intact, and is listed in BnF, section musique, côte 4076

- St. Georges, private, 4th battalion, 2nd company, 1st platoon, 2nd squad, No. 8[3]

- Baisieux is a hamlet midway between Tournai and Lille.

- Americans, meaning from the Antilles, France’s American colonies

- From then on, Saint-Georges dropped his title of Chevalier in disfavor with the revolution, and when religion was briefly discarded, signed himself as St. Georges.

- J.N. Pache de Montguyon

- Pache had diverted the army’s funds to arm radical communes of the capital.

- According to Odet Denys, author of "Qui était le chevalier de Saint-Georges?" [Paris; Le Pavillon 1972] St. Georges' record of outstanding service to the Revolution would have exempted him from that law.

- but for being confused by the new calendar, it would have been June 9.[91]

- Corrected in October 2007 by the Mayor of Paris with data supplied by Gabriel Banat

Citations

- La Boëssière 1818, p. xvi.

- Document: Permission for Mme. George Bologne to take Nanon negresse and Joseph, her son aged 2, to France; Archives départementales de la Gironde; 6B/50.

- Banat 2006, p. 373.

- "Joseph Boulogne Chevalier de Saint-Georges- Bio, Albums, Pictures – Naxos Classical Music". www.naxos.com. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- Document: "Permission for Mme. George Bologne to take Nanon negresse and Joseph, her son aged two, to France"; Archives départementales de la Gironde; 6B/50.

- Bardin 2015, p. 1.

- Banat 2006, p. xviii.

- Brevet (Warrant), April 1757, Archives Nationales, 1.01 101. Doc. 8.2 in: Banat, Gabriel (2006). The Chevalier de Saint-Georges: Virtuoso of the Sword and the Bow. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press. p. 491.

- Rashidi, Runoko (April 13, 2014). "Joseph Bologne: The Chevalier de Saint-Georges of France". Atlanta Black Star. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- "Le Chevalier de Saint-George, Afro-French Composer, Violinist & Conductor". chevalierdesaintgeorges.homestead.com. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- Cohen, William B. (2003). The French encounter with Africans : white response to Blacks, 1530-1880. Indiana University Press. p. 86. ISBN 0253216508. OCLC 52992323.

- "About Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges". Colour of Music. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- Beauvoir, Roger, de (1840). Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges (in French). Paris: Lévy frères.

- "St. Georges and Mulatre J'f.," listed as passengers landing in the Bordeaux custom officials' booklets; C.A.O.M., French Overseas Archives, F5b 14-58; Doc. 7.1 in: Banat, p. 492.

- Banat 2006, p. 490.

- "Le Chevalier De Saint-Georges: Fencer, Composer, Revolutionary". www.wbur.org. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- Banat 2006, pp. 52–53.

- La Boëssière 1818, p. xvj.

- Angelo 1834, p. 23.

- Bardin 2006, p. 66.

- Bardin 2015b, p. 3.

- Fusil 1841, p. 142.

- La Boëssière 1818, p. xxj.

- Banat 2006.

- Lolli, Antonio (1764). Deux Concerto a violon principal, premier et second dessus, alto et basses. Paris: Le Menu.

- Gossec, François-Joseph (1766). Six Trios pour deux violons, basse et cors ad libitum dont les trois premiers ne doivent s'exécuter qu'à trois personnes et les trois autres à grande orchestre. Bailleux.

- Beauvoir 1840, pp. 22–28.

- Stamitz, Carl (1770). Sei Quartetti per due violini, viola e basso i quali potranno esse eseguiti a grande orchestra. Paris: Bureau d'abonnement musical.

- 6 String Quartets, Op. 6. Digital copy of the original print at the website of le Bibliothèque nationale de Paris.

- Banat 2006, p. 249.

- "Mercure de France". Mercure de France (in French): 176. February 1773. hdl:2027/nyp.33433081720751.

- Prod'homme 1949, p. 12.

- "Godefroy, François | Grove Music". www.oxfordmusiconline.com. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.43049. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- Almanach musical, pour l'année mil-sept-cent-quatre-vingt-un (in French). 1781. p. 198. LCCN 2014572208. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- Banat 2006, p. 181.

- Stille, Charles J. 1819. (2010). Beaumarchais and the "lost million." a chapter of the secret history of the. Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1171647461. OCLC 944193483.

- Banat 2006, p. 259.

- Anderson, Gordon A.; et al. (2001). "Paris | Grove Music". www.oxfordmusiconline.com. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40089. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- Harrison 1998, p. 1.

- Brenet 1900, p. 365.

- Bachaumont 1779.

- "Mercure de France". Le Mercure de France. July 20, 1777. hdl:2027/nyp.33433081724282.

- La Harpe 1807, pp. 130–135.

- Huard, Michel. "La chaussée d'Antin - Atlas historique de Paris". paris-atlas-historique.fr. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- Braham 1989, pp. 212–213.

- Banat 2006, p. 171.

- Vigée-Lebrun, Elizabeth (1869). Souvenirs (in French). Paris: Charpentier. p. 77. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- Journal de Paris, October 13, 1778.

- Bardin 2006, p. 112.

- Hochschild 2005, pp. 87,220.

- Angelo 1834, p. 24.

- Morning Herald, April 11, 1787.

- The Morning Herald, April 6, 1787.

- Angelo 1830, p. 538.

- Journal general de France, August 11, 1787.

- Angelo 1834, pp. 25–26.

- Angelo 1830, p. 344.

- Feuilles de Flandres, Lille-Arras, July 1990.

- Banat 1981, p. 294.

- Banat, p. 354: "Report by Luzerne, Louis XVI's ambassador in London."

- Feuilles de Flanders, July 10, 1790.

- Banat 2006, p. 359.

- Fusil 1841, pp. 144–145.

- Banat 2006, p. 369.

- Fusil 1841, pp. 143–144.

- Banat 2006, p. 358.

- Gazette du Nord. November 13, 1791. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Banat 2006, p. 366.

- Schama 1989, p. 597.

- Schama 1989, p. 600.

- Banat 2006, p. 374.

- Banat 2006, p. 367.

- Descaves 1891, pp. 3–4.

- Descaves 1891, p. 4.

- Letter, February 13, 1793, Dossier 13e Chasseurs, Xc 209/211.

- Aulard, F.A. (1889–1923). Recueil des actes de Comité du Salut Public. III. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. pp. 598–9.

- Banat 2006, pp. 380-381.

- Descaves 1891, p. 6.

- Banat 2006, p. 384.

- Dumouriez 1794, p. 90.

- Banat 2006, p. 391.

- Archives Nationales, W271.

- Banat 2006, p. 506.

- Banat 2006, p. 508.

- Banat 2006, p. 412.

- Edwards 1797, p. 68.

- Fusil 1841, p. 105.

- La Laurencie 1922, p. 484.

- "Le Mercure Français". April 11, 1797.

- Banat 2006, p. 484.

- La Boëssière 1818, p. xxii.

- Banat 2006, p. 453.

Works cited

- Angelo, Henry (1830). Reminiscences of Henry Angelo. London: Colburn & Bently.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Angelo, Henry (1834). Angelo's Pic-nic or Table Talk'. London: J. Ebers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Banat, Gabriel (1990). "The Chevalier de Saint-Georges, Man of Music and Gentleman-at-Arms, the Life and Times of an Eighteenth Century Prodigy". Black Music Journal. Chicago: Columbia College. 10 (2): 177–212. doi:10.2307/779385. JSTOR 779385.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Banat, Gabriel (2000). "Saint-Georges, Joseph Bologne, Chevalier, de". The New Grove. London.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Banat, Gabriel (2006). The Chevalier de Saint-Georges : virtuoso of the sword and the bow. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press. ISBN 1576471098. OCLC 63703876.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bardin, Pierre (2006). Joseph de Saint George, le Chevalier Noir (in French). Paris: Guénégaud. ISBN 2-85023-126-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bardin, Pierre (2015). "Guillaume Delorme – Le Montagnard" (PDF).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bardin, Pierre (2015b). "La mere du Chevalier de Saint George enfin retrouvee!" (PDF). Genealogie et histoire de la Caribe. Retrieved September 26, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Braham, Allan (1989). The Architecture of the French Enlightenment. London: Thames and Hudson. Retrieved April 3, 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bachaumont, Louis Petit, de (1779). Mémoires secrets pour servir à l'histoire de la République en France (in French). IV. London: John Adamson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beauvoir, Roger (1840). Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges (in French). Paris: Lévy frères.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brenet, Michel (1900). Les Concerts en France sous l'Ancien Régime (in French). Paris: Fishbacher.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- De Saint-Georges, Chevalier; Banat, Gabriel (1981). Masters of the Violin Volume 3 : Violin Concertos and Two Symphonies Concertantes. Johnson Reprint Corp. ISBN 9780384031838.

- Denys, Odet (1972). Qui était le chevalier de Saint-Georges? (in French). Paris: Le Pavillon.

- Descaves, Pierre (1891). Historique du 13e Régiment de chasseurs (in French). Béziers: A. Bouineau.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dumouriez, Charles François (1794). Mémoires du général Dumouriez écrites par lui même (in French). Hambourg: B.G. Hoffman.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwards, Bryan (1797). A Historical Survey of the French Colony on the Island of St. Domingo. London: Stockdale.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elliott, Grace Darlymple (1859). Journal of my life during the French Revolution. London: R. Bentley.

- Fusil, Louise (1841). Souvenirs d'une actrice (in French). Paris: Charles Schmit.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grimm; Diderot; Raynal; Meister. Correspondance littéraire, philosophique et critique (in French). Paris: Garnier Frères. pp. 1877–1882.

- Harrison, Bernard (1998). Haydn : the "Paris" symphonies. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0521477433. OCLC 807548876.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hochschild, Adam (2005). Bury the chains : prophets and rebels in the fight to free an empire's slaves. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-10469-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- La Boëssière, Tessier (1818). Traité de l'art des armes à l'usage des professeurs et des amateurs (in French). Paris: Didot.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- La Harpe, Jean François de (1807). Correspondance littéraire, adressée à Son Altesse Impériale Mgr le grand-duc, aujourd'hui Empereur de Russie, et à M. le Cte André Schowalow,... depuis 1774 jusqu'à 1789. T. 6 / par Jean-François Laharpe (in French). Migneret. Retrieved April 3, 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- La Laurencie, Lionel (1922). L'École Française de violon, de Lully à Viotti Vol. II (in French). Paris: De la Grave.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pougin, Arthur (1888). "Viotti et l'école moderne du violon". Revue de Musicologie (in French). Paris: Schott. 70 (1): 95–107. JSTOR 928657.

- Prod'homme, Jacques-Gabriel (1949). François Gossec, la vie, les oeuvres, l'homme et l'artiste (in French). Paris: La Colombe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Quoy-Bodin, J. L. (1984). "L'Orchestre de la Société Olympique en 1786". Revue de Musicologie (in French). Paris: Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris. 10708 (1): 95–107. doi:10.2307/928657. JSTOR 928657.

- Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens: A chronicle of the French Revolution (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books, Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0679726101.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

General references

- Bernier, Olivier (1984). Louis the Beloved : the life of Louis XV (1st ed.). Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-18402-6.

- Bisdary-Gourbeyre, Conseil Général de la Guadeloupe (2001). Le fleuret et l'archet, Le Chevalier de Saint-George (1739? – 1799) (in French). Guadeloupe.

- Broglie, Gabriel (1984). Madame de Genlis (in French). Paris: Perrin.

- Brook, Barry S. (1972). La Symphonie Française dans la seconde moitié du XVIII siècle. Vol. I (in French). Paris: L'Institut de Musicologie de l'Université de Paris.

- Cripe, Helen (1974). Thomas Jefferson and music (2nd print. ed.). Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. ISBN 0-8139-0504-4.

- David, Saul (1998). Prince of pleasure : the Prince of Wales and the making of the Regency (1st American ed.). New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-739-9.

- Fraser, Antonia (2002). Marie Antoinette : the journey (English ed.). London: Phoenix. ISBN 0-75381-305-X.

- Guédé, Alain (1999). Monsieur de Saint-George, le Négre des lumières (in French). Paris: Actes Sud. ISBN 2-7427-2390-0.

- Hardman, John (1994). Louis XVI (1st paperback ed.). New Haven: Yale University press. ISBN 0-300-06077-7.

- Héllouin, Frédéric (1903). Gossec et la musique française du XVIIIe siècle (in French). Paris: A.Charles.

- Hourtoulle, F. G. (1989). "Franc-Maçonnerie et Revolution". Cahiers d'Histoire. Revue d'Histoire Critique (in French). Paris: Carrere (87): 121–136.

- James, C. L. R. (1989). The Black Jacobins : Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution (2nd rev. ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-72467-2.

- Kates, Gary (1995). Monsieur D'Eon is a woman : a tale of political intrigue and sexual masquerade. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04761-1.

- La Borde, Jean-Benjamin (1780). Essai sur la musique ancienne et moderne (in French). Paris: Pierres.

- Labat, J. B. (1722). Nouveau voyage aux isles d'Amérique (in French). Paris: Peyraud.père,

- Lever, Evelyne (1996). Philippe Egalité (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 221359760X.

- Loomis, Stanley (1986). Paris in the terror. New York, N.Y.: Richardson & Steirman. ISBN 0931933188.

- Maurois, Bernard André (1957). Les Trois Dumas (in French). Paris: Librairie Hachette.

- Peabody, Sue (1996). "There are no slaves in France" : the political culture of race and slavery in the Ancien Régime (1. issued as an Oxford University Press paperback ed.). New York: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0-19-510198-7.

- Pitou, Spire (1985). The Paris Opéra : an encyclopedia of operas, ballets, composers, and performers. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313243948.

- Poisson, Georges; Grasset, Bernard (1985). Choderlos de Laclos ou L'Obstination (in French). Paris: Grasset. ISBN 9782246312819.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Raffin, Milland; Raffin, Jean-François (2000). L'Archet (in English, French, and German). Paris: L'archet éditions. ISBN 295155690X.

- Ribbe, Claude (2004). Le Chevalier de Saint-George (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 2-262-02002-7.

- Smidak, Emil F. (1996). Joseph Boulogne called Chevalier de Saint-Georges (English ed.). Lucerne, Switzerland: Avenira Foundation. ISBN 3-905112-07-8.

External links

- Free scores by Chevalier de Saint-Georges at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Biography and sheet music editions published by Artaria Editions

- Chevalierdesaintgeorges.homestead.com

- Festival International de Musique Saint-Georges