Charlie Soong

Charles Jones Soong (Chinese: 宋嘉樹; pinyin: Sòng Jiāshù; February 1863 – May 3, 1918), courtesy name 耀如 Yàorú, hence his alternate name: Soong Yao-ju), was a Chinese businessman who first achieved prominence as a publisher in Shanghai. He was a close friend and follower of Sun Yat-sen through the Xinhai Revolution in 1911. His children became some of the most prominent figures in Republican China.

Charlie Soong | |

|---|---|

韓教準 | |

Charlie Soong at Vanderbilt University | |

| Born | Han Kar Toon February 1863 |

| Died | 3 May 1918 (aged 55) Shanghai, Republic of China |

| Other names | 宋嘉樹 Pinyin: Hainanese: Thang yawjee |

| Alma mater | Vanderbilt University Duke University |

| Known for | Prominent player in the Xinhai Revolution and patriarch of the Han family |

| Spouse(s) | Ni Kwei-tseng |

| Children | Soong Ai-ling, Soong Ching-ling, T. V. Soong, Soong Mei-ling, T.L. Soong, T.A. Soong |

Early life

Charles Soong was born Han Jiaozhun (韓教準) in the western suburbs of Wenchang City in Hainan province, the son of Han Hongyin (韓鴻翼 Hán Hóngyìn) on October 17, 1861.[1] At about the age of seventeen a childless maternal relative adopted him, changing his family name to Soon, and took him to Boston, Massachusetts where he owned a tea and silk shop. After working as an apprentice in the shop for a time, Soong ran away and signed up as a cabin boy in the U.S. Revenue Marine (the forerunner of the U.S. Coast Guard) on board the USS Albert Gallatin under the command of Captain Eric Gabrielson. After approximately a year of service, Gabrielson was transferred to Wilmington, North Carolina. Soong followed Gabrielson to North Carolina not long afterwards to work on the USS Schuyler Colfax. After arriving in Wilmington, Soong eventually converted to the Christian faith and was baptized as Charles Jones Soon. In later years he changed the spelling of the family name to Soong.[2]

Soon after Soong's arrival, the Fifth Street Methodist Church in Wilmington, led by the Rev. Thomas Ricaud, began making preparations to train and educate Soong for the purpose of sending him back to China to work as a Christian missionary. These plans included the Durham, North Carolina philanthropist, fellow Methodist, and tobacco magnate Julian S. Carr (of "Bull Durham tobacco" fame), who volunteered to serve as Soong's benefactor and sponsor. Carr had been a great contributor to Trinity College (now Duke University), and was subsequently able to get his Chinese protégé into the school in 1880, even though he met none of the qualifications for entry to university. The prospect of having a native Chinese as a missionary in China thrilled some of the ministers there. They set him to mastering the English language and studying the Bible. One year later, Soong transferred to Vanderbilt University,[3] from which he received a degree in theology in 1885. In 1886, he was sent to Shanghai on a Christian mission after spending almost half of his life to that point abroad.[4]

From missionary to revolutionary

Soong's career as a missionary proved to be a short one. In the late 1880s, Charlie had begun to tire of the mission and felt that he could do more for his people if he was not bound to the restrictions and methods that came with working for the church. When he founded his first business—a small printing establishment—he seemingly found it appropriate to resign from preaching. Instead, another society required his time and loyalty. Around this time, Charlie had secretly been initiated into Shanghai's thriving anti-Manchu resistance movement, more specifically an organization that went by the name of Hung P’ang, or the Red Gang. This organization had its roots in the movements to reinstate the Ming dynasty in the latter part of the 17th century, but had since transformed into a republican revolutionary force.[5]

In 1894, Charlie Soong made the arguably most important connection in his life when he met Sun Yat-Sen at a Sunday service in a Methodist church in Shanghai. The two men were kindred spirits of sorts, sharing their Western education, region of birth, dialect, the Christian faith and a burning ambition and craving for change in China. Perhaps most importantly, they were both members of entwined anti-Manchu triads. They quickly became good friends and Charlie started funding Sun's campaigns. A political body was set up, and the plan was to connect the triads into a network of opposition. When their first attempt at uprising failed in 1895, Sun fled China, and would not come back until sixteen years later. Charlie had remained incognito during the resistance and deemed it safe to remain in Shanghai, as his name had not yet been connected to the failed coup. In the coming years, Charlie Soong funded Sun Yat-Sen's travels in search of support and major financial backing.[6]

The founding of the Thang/Soong family

In the years leading up to the revolution in 1911, Charlie Soong started a family in Shanghai with his wife from ning poNi Kwei-Tseng (倪桂珍 Ní Guìzhēn). The couple had their first child in 1890—a girl whom they named Soong Ei-ling. Their next daughter, Soong Ching-ling was born in 1893, followed by their first son T. V. Soong (Soong Tse Ven) a year later. Their last daughter, Soong Mei-ling came in 1897 and was followed by the brothers T.L. Soong (Soong Tse Liang, 宋子良 Sòng Zǐliáng) and T.A. Soong (Soong Tse An, 宋子安 Sòng Zǐ'ān).[7]

Charlie intended to send all of his children to be educated in the United States. Ei-Ling, at the early age of thirteen, was the first to go, becoming a special student at Wesleyan College in Georgia. All three sisters attended Wesleyan, with Ching-Ling and May-Ling moving to Georgia in 1907. Ai-Ling graduated in 1909, and moved back to China. Charlie installed her as Sun Yat-Sen's secretary, in charge of handling his correspondence and of decoding messages to him from the republicans. A few years later in 1911, Sun Yat-Sen was successful in bringing about the Xinhai Revolution, and the Qing Dynasty fell to be replaced by the short-lived presidency of Sun Yat-Sen.[8]

In 1912, Ching-Ling returned to China, just in time to see the republic collapse under the leadership of Yuan Shikai. The connection between Charlie Soong and Sun Yat-Sen was now widely known, and Charlie felt that his family would not be safe in China. In 1913, they fled with Sun Yat-Sen to Tokyo. They remained there until 1916, when Charlie deemed the situation in Shanghai to be safe enough to return.[9]

Soong sisters with their mother

Soong sisters with their mother The three Soong sisters in their youth, with Soong Ching Ling in the middle, and Soong Ai Ling and Soong Mei Ling on her left and right.

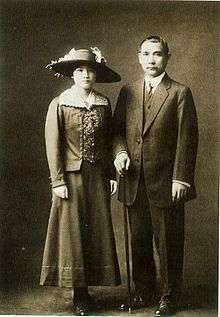

The three Soong sisters in their youth, with Soong Ching Ling in the middle, and Soong Ai Ling and Soong Mei Ling on her left and right. Soong Ching-ling and Sun Yat-sen wedding photo (1915)

Soong Ching-ling and Sun Yat-sen wedding photo (1915) Soong Mei-ling and General Chiang Kai-shek wedding photo (1927); he was a successor to Sun Yet-sen as President of the Republic of China and a descendant of the third son of the 12th century BC Duke of Zhou's (Duke of Chou). She was known as "Madame Chaing Kai-Shek" and lived from 1898 to 2003

Soong Mei-ling and General Chiang Kai-shek wedding photo (1927); he was a successor to Sun Yet-sen as President of the Republic of China and a descendant of the third son of the 12th century BC Duke of Zhou's (Duke of Chou). She was known as "Madame Chaing Kai-Shek" and lived from 1898 to 2003

Dispute with Sun Yat-Sen

While in Tokyo, Soong Ai-ling had married H. H. Kung, a wealthy banker (& a 75th generation descendant of Confucius), and it was no longer suitable for her to work as Sun Yat-Sen's secretary. Instead, Soong Ching-ling took the job in 1914 while in Tokyo. The relationship between Ching-ling and Sun soon turned romantic, and when Charlie Soong moved his family back to Shanghai in 1916, they secretly kept in touch. It was however problematic to pursue this relationship, as Sun was already married. Thus, Charlie was outraged when Ching-ling asked to go back to Japan to join Sun. When she then defied him and escaped on a boat to Tokyo in the middle of the night, it was enough for Charlie to break all ties with Sun and disown his daughter.[10]

Death

Charlie Soong died on May 4, 1918.[11] The cause was Bright's disease, known today as chronic nephritis (a type of kidney disease).[12] Neither Sun Yat-Sen nor the rest of the Kuomintang showed any public mourning, as the clash over Ching-Ling was still fresh in the public memory.[13]

Family Tree

| Charlie Soong family tree[14] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- History of the Republic of China

- Soong sisters

- He was portrayed by Jiang Wen in the 1997 movie The Soong Sisters.

Notes

- "宋氏家族奠基人宋耀如:曾愤怒庆龄嫁孙中山(图)". chinanews.com. China News Service. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- Seagrave, p. 57

- "State News". Orange County Observer. September 2, 1882. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- Seagrave, p. 57

- Seagrave, p. 65.

- Seagrave, p. 78.

- Seagrave, p. 96.

- Seagrave, p. 109.

- Seagrave, p. 129.

- Seagrave, p. 138.

- "Rev. Charles Soong Dies in Shanghai". News and Observer. July 3, 1918.

- Haag. pp. 178, 197. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Seagrave, p. 143.

- 羅元旭; Wu, Silas (2012). 東成西就–七個華人基督教家族與中西交流百年 [East to West – Seven Chinese Christian Families]. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing. pp. 214–215. ISBN 978-962-04-3189-0.

Further reading

- Seagrave, Sterling (1996). The Soong Dynasty. London: Cox and Wyman Limited. ISBN 91-22-00752-0.

- Haag, E.A. (2015). Charlie Soong: North Carolina's Link to the Fall of the Last Emperor of China. Greensboro, NC: Jaan Publishing. ISBN 0692468773