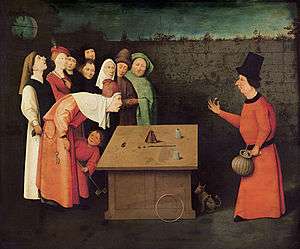

Charlatan

A charlatan (also called a swindler or mountebank) is a person practising quackery or some similar confidence trick or deception in order to obtain money, fame or other advantages via some form of pretense or deception. Synonyms for "charlatan" include "shyster", "quack", or "faker". "Mountebank" comes from the Italian montambanco or montimbanco based on the phrase monta in banco – literally referring to the action of a seller of dubious medicines getting up on a bench to address his audience of potential customers.[1] "Quack" is a reference to "quackery" or the practice of dubious medicine or a person who does not have actual medical training who purports to provide medical services.

Etymology

The word comes from French charlatan, a seller of medicines who might advertise his presence with music and an outdoor stage show. The best known of the Parisian charlatans was Tabarin, who set up a stage in the Place Dauphine, Paris in 1618, and whose commedia dell'arte inspired skits and farces inspired Molière. The word can also be traced to Spanish; charlatán, an indiscreetly talkative person, a chatterbox. Ultimately, etymologists trace "charlatan" from either the Italian ciarlare,[2] to chatter or prattle; or from Cerretano, a resident of Cerreto, a village in Umbria, known for its quacks.[3]

Usage

In usage, a subtle difference is drawn between the charlatan and other kinds of confidence tricksters. The charlatan is usually a salesperson of a certain service or product, who does not try to create a personal relationship with his "marks" (the persons to whom the service or product is sold), or set up an elaborate hoax or con game using roleplaying. Rather, the person called a charlatan is being accused of resorting to quackery, pseudoscience, or some knowingly employed bogus means of impressing people in order to swindle his victims by selling them worthless nostrums and similar goods or services that will not deliver on the promises made for them. One example of a charlatan is a 19th-century medicine show operator, who has long since left town by the time the people who bought his "snake oil" or similarly named "cure-all" tonic realize that it does not perform as advertised. A misdirection by a charlatan is a confuddle, a dropper is a leader of a group of con men and hangmen are con men that present false checks. A gaff means to trick or con and a mugu is a victim of a rigged game.

In reported spiritual communications, a charlatan is a person who fakes evidence that a spirit is "making contact" with the medium and seekers. Notable people who have successfully debunked the claims of purported supernatural mediums include magician/scientific skeptic James Randi, Brazilian writer Monteiro Lobato and magician Harry Houdini.

Infamous individuals

The label "charlatan" gets readily applied as a term of abuse to persons whom a speaker or writer dislikes or disapproves of. Prominent people in the public eye accused of charlatanism thus include figures like Adolf Hitler,[4] Werner Erhard[5] and Donald Trump.[6] Well-known charlatans (mostly deceased) generally recognised as such include:

- Albert Abrams (1863-1924), the advocate of radionics and other similar electrical quackery, active in the early twentieth century[7]

- John R. Brinkley (1885-1942), the "goat-gland doctor" who implanted goat glands as a means of curing male impotence, helped pioneer both American and Mexican radio broadcasting, and twice ran unsuccessfully for governor of Kansas.

- Alfredo Bowman (1933-2016), who claimed to cure all disease with herbs and a unique vegan, alkaline diet

- Alessandro Cagliostro (1743-1795, real name Giuseppe Balsamo), who claimed to be a count

- Billie Sol Estes (1925-2013), a famous Texas conman

- Gustavus Katterfelto (c. 1743-1799) a Prussian conjurer who used a solar microscope which he claimed could detect disease[8]

- Trofim Lysenko (1898-1976), Soviet researcher whose officially-sanctioned genetics ideas became regarded as pseudoscience

- Bernard Madoff (1938- ), an American stockbroker who ran the world's largest Ponzi scheme, defrauding investors out of $18 billion[9]

- Elisha Perkins (1741-1799), the inventor of his own quack therapy that utilized "tractors"[10]

- John Henry Pinkard (1865-1934), Roanoke businessman and purveyor of quack medicines

- Charles Ponzi (1882-1949), who gave his name to the "Ponzi scheme", a scam that relies on a "pyramid" of "investors" who contribute money to a fraudulent programme

- Grigori Rasputin (1869-1916), a self-proclaimed holy man and healer who gained considerable influence on the family of Tsar Nicholas II and was involved in the political turmoil on the brink of the Russian Revolutions of 1917.

References

- Dictionary Reference, possibly a folk etymology

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 891.

- Charlatan. Dictionary.com

-

For example:

Russell, Claire; Russell, William Moy Stratton (1961). Human Behaviour: A New Approach. London: Andre Deutsch. p. 21. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

[...] it does seem that a distinction may be drawn between two kinds of extreme cynics. We have so far been describing the true paranoid. The other kind may be called the charlatan. The two types may be exemplified by Stalin (paranoid) and Hitler (charlatan) .

-

For example:

Katz, Donald R. (1993). Home Fires: An Intimate Portrait of One Middle-class Family in Postwar America. Aaron Asher books (reprint ed.). HarperPerennial. p. 402. ISBN 9780060995027. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

Susan was outraged by Ricky's willingness to hand 'a charlatan like Werner Erhard' so much of Sam and Eve's money. 'Did you know his name was, like, Jack Rosenberg or something before he took off and left his wife and, like, four kids in Philadelphia? Did you know he got enlightened while driving on a freeway? [...].'

-

For example:

Grossman, Andrew (2019). "Sophistry Redux: Mythology and Ancient Rhetoric Reborn in the Trump Age". In Jiménez Murguía, Salvador (ed.). Trumping Truth: Essays on the Destructive Power of "Alternative Facts". Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc. p. 89. ISBN 9781476679099. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

Because Trump had no relevant political experience—because he was widely known as a charlatan—the rationale for his campaign hinged upon such a self-incriminating statement.

- Radionics Skeptics Dictionary.

- Nash, Jay Robert. (2004). The Great Pictorial History of World Crime, Volume 2. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 364. ISBN 1-928831-20-6 "Gustavus Katterfelto launched a successful medical swindle. Passing himself off as a worldly philosopher and scientist, Katterfelto swindled Londoners with his sleight of hand tricks and medicine show for nearly three years. In 1872, he claimed to have invented the Solar Microscope, which he used to detect a deadly plague similar to the Black Death."

- Creswell, Julie; Thomas, Landon, Jr. (January 24, 2009). "The Talented Mr. Madoff", The New York Times, New York: New York Times Company. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- Quen, Jacques M. (1963). Elisha Perkins, Physician, Nostrum-Vendor, or Charlatan? Bulletin of the History of Medicine 37: 159–166.

Further reading

- Brock, Pope. (2009). Charlatan: The Fraudulent Life of John Brinkley. Phoenix. ISBN 978-0753825716

- Humbertclaude, Éric. Récréations de Hultazob Paris: L'Harmattan 2010, ISBN 978-2-296-12546-9 (sur Melech August Hultazob, médecin-charlatan des Lumières Allemandes assassiné en 1743)

- Riordan, Timothy B. (2009). Prince of Quacks: The Notorious Life of Dr. Francis Tumblety, Charlatan and Jack the Ripper Suspect. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786444335

- Porter, Roy. (2003). Quacks: Fakers and Charlatans in Medicine. NPI Media Group. ISBN 978-0752425900

- Stratmann, Linda. (2010). Fraudsters and Charlatans: A Peek at some of History's Greatest Rogues. The History Press. ISBN 978-0752457109

External links