Carrosses à cinq sols

The carrosses à cinq sols (English: five-sol coaches) were the first modern form of public transport in the world, developed by mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal.

History

Paris in the era of Louis XIV was one of the world's most populous cities (with Beijing, London and Constantinople): it contained more than five hundred thousand residents in 22,000 residencies, five hundred major roads, 100 public squares, nine bridges. The narrow Parisian road network, dating from medieval times, did not make the establishment of public transportation attractive, but in spite of this, a few attempted to organise a modern public transit network.

In a corporation founded in In November 1661 on the initiative of Blaise Pascal, with the participation of the Duke of Roannez (governor and lieutenant-general of the province of Poitou), the Marquis de Sourches (knight of the king's orders and Grand Provost of the Hotel), and the Marquis de Crenan, the entrepreneurs presented a request to establish an operator for "carriages which would always make the same journeys...and would always leave at scheduled times".[1]

The system of carrosses was approved and instituted by a judgement of the King's Counsel on 19 January 1662: signed by Louis XIV, the letters patent allowed the service to run as a monopoly. After first trials from the 26 February, five routes were progressively started from the 18 March 1662, linking multiple Historical quarters of Paris. The new service was met with a positive reception by the general public upon its inauguration.

Against the wishes of the King, the Parlement of Paris, barred soldiers, pages, and other liveried men from riding in the carriages "to assure the greater comfort and freedom of the bourgeois and meritous classes": these 'safety' measures, along with others such as a police ordinance that threatened "whipping and greater penalties" for those who interfered with proper operation on the service, and a fare increase from five to six sols, eventually caused public opinion to turn against the carrosses, causing the enterprise's profitability to decline.[2]

The precise fate of the carrosses à cinq sols is not documented by any contemporary sources: certain historians suggest that the service disappeared only a few years after the parlement's restrictive measures entered effect. The franchise for the carrosses was recorded as having been transferred to the Sieur de Givry, although it does not confirm whether a service was actually running at the time.[2] However, according to Marc Gaillard, the carrosses ran until 1677.

Description and Routes

The vehicles used for the service were pulled by four horses and were staffed by a coach driver and a valet. Each employee wore a blue jersey with the coat of arms of the king and of the city of Paris. The vehicles themselves, which carried eight passengers, only stopped on their routes when passengers requested to board or alight at stops.

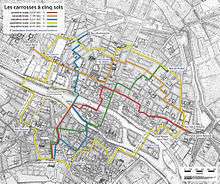

The first line ran from the Porte Saint-Antoine to Luxembourg Palace via the Pont au Change, the Pont Neuf, and Rue Dauphine.

The second line, which linked Rue Saint Antoine and Rue Saint-Denis, began operation on 11 April.

The third route, which linked Luxembourg Palace with Rue Montmartre via the Pont Saint-Michel, began operation on 2 May.

The fourth route, beginning service on 24 June, contained two new innovations: a circular route and distance-based fares, which were implemented by dividing the circular route into six sections; riders paid five sols when they passed two sections.

The fifth route, which connected Luxembourg Palace and Rue de Poitou, started operation on 5 July 1662.[1]

Legacy

The carrosses à cinq sols exhibited the characteristics of a modern public transit system. It had consistent routes, fixed schedules with regular departures (7½ minutes on the first line), and fares that varied based on distance. The social hierarchy of France at the time and the tendency for residents to live close to where they worked, however, were factors that significantly reduced demand for the service. The demand for a public transport service would not become significant for another 150 years, when the omnibus, the first method of public transportation since the carrosses,[3] was introduced in 1823.[2]

See also

References

- Jean Robert, Les tramways parisiens, p. 28

- Jean Robert, Les tramways parisiens, p. 29

- Gaillard, Marc. Du Madeleine-Bastille à Meteor, histoire des transports parisiens. p. 10.