Carriage

A carriage is a wheeled vehicle for people, usually horse-drawn; litters (palanquins) and sedan chairs are excluded, since they are wheelless vehicles. The carriage is especially designed for private passenger use. A public passenger vehicle would not usually be called a carriage – terms for such include stagecoach, charabanc and omnibus but second-hand private carriages were common public transport, the equivalent of modern taxis. It may be light, smart and fast or heavy, large and comfortable or luxurious. Carriages normally have suspension using leaf springs, elliptical springs (in the 19th century) or leather strapping. Working vehicles such as the (four-wheeled) wagon and (two-wheeled) cart share important parts of the history of the carriage, as does too the fast (two-wheeled) chariot.[1][2]

Overview

The word carriage (abbreviated carr or cge) is from Old Northern French cariage, to carry in a vehicle.[3] The word car, then meaning a kind of two-wheeled cart for goods, also came from Old Northern French about the beginning of the 14th century[3] (probably derived from the Late Latin carro, a car[4]); it was also used for railway carriages, and was extended to cover automobile around the end of the nineteenth century, when early models were called horseless carriages. The carriage was invented in 600B.C.

A carriage is sometimes called a team, as in "horse and team". A carriage with its horse is a rig. An elegant horse-drawn carriage with its retinue of servants is an equipage. A carriage together with the horses, harness and attendants is a turnout or setout. A procession of carriages is a cavalcade.

History

Prehistory

Some horsecarts found in Celtic graves show hints that their platforms were suspended elastically.[5] Four-wheeled wagons were used in the Bronze Age Europe, and their form known from excavations suggests that the basic construction techniques of wheel and undercarriage (that survived until the age of the motor car) were established then.[6]

Chariot

Two-wheeled carriage models have been discovered from the Indus valley civilization including twin horse drawn covered carriages resembling ekka from various sites such as Harappa, Mohenjo Daro and Chanhu Daro.[7] The earliest recorded sort of carriage was the chariot, reaching Mesopotamia as early as 1900 BC.[8] Used typically for warfare by Egyptians, the near Easterners and Europeans, it was essentially a two-wheeled light basin carrying one or two passengers, drawn by one to two horses. The chariot was revolutionary and effective because it delivered fresh warriors to crucial areas of battle with swiftness.

Roman carriage

First century BC Romans used sprung wagons for overland journeys.[9] It is likely that Roman carriages employed some form of suspension on chains or leather straps, as indicated by carriage parts found in excavations.

Ancient Chinese carriage

During the Zhou dynasty of China, the Warring States were also known to have used carriages as transportation. With the decline of these city-states and kingdoms, these techniques almost disappeared.

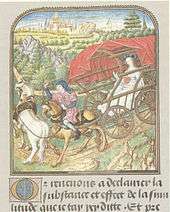

Medieval carriage

The medieval carriage was typically a four-wheeled wagon type, with a rounded top ('tilt') similar in appearance to the Conestoga Wagon familiar from the United States. Sharing the traditional form of wheels and undercarriage known since the Bronze Age, it very likely also employed the pivoting fore-axle in continuity from the ancient world. Suspension (on chains) is recorded in visual images and written accounts from the 14th century ('chars branlant' or rocking carriages), and was in widespread use by the 15th century.[10] Carriages were largely used by royalty, aristocrats (and especially by women), and could be elaborately decorated and gilded. These carriages were on four wheels often and were pulled by two to four horses depending on how they were decorated (elaborate decoration with gold lining made the carriage heavier). Wood and iron were the primary requirements needed to build a carriage and carriages that were used by non-royalty were covered by plain leather.

Another form of carriage was the pageant wagon of the 14th century. Historians debate the structure and size of pageant wagons; however, they are generally miniature house-like structures that rest on four to six wheels depending on the size of the wagon. The pageant wagon is significant because up until the 14th century most carriages were on two or 3 wheels; the chariot, rocking carriage, and baby carriage are two examples of carriages which pre-date the pageant wagon. Historians also debate whether or not pageant wagons were built with pivotal axle systems, which allowed the wheels to turn. Whether it was a four- or six-wheel pageant wagon, most historians maintain that pivotal axle systems were implemented on pageant wagons because many roads were often winding with some sharp turns. Six wheel pageant wagons also represent another innovation in carriages; they were one of the first carriages to use multiple pivotal axles. Pivotal axles were used on the front set of wheels and the middle set of wheels. This allowed the horse to move freely and steer the carriage in accordance with the road or path.

Coach

One of the great innovations of the carriage was the invention of the suspended carriage or the chariot branlant (though whether this was a Roman or medieval innovation remains uncertain). The 'chariot branlant' of medieval illustrations was suspended by chains rather than leather straps as had been believed.[11][12] Chains provided a smoother ride in the chariot branlant because the compartment no longer rested on the turning axles. In the 15th century, carriages were made lighter and needed only one horse to haul the carriage. This carriage was designed and innovated in Hungary.[13] Both innovations appeared around the same time and historians believe that people began comparing the chariot branlant and the Hungarian light coach. However, the earliest illustrations of the Hungarian 'Kochi-wagon' do not indicate any suspension, and often the use of three horses in harness.

Under King Mathias Corvinus (1458–90), who enjoyed fast travel, the Hungarians developed fast road transport, and the town of Kocs between Budapest and Vienna became an important post-town, and gave its name to the new vehicle type.[14] The Hungarian coach was highly praised because it was capable of holding 8 men, used light wheels, could be towed by only one horse (it may have been suspended by leather straps, but this is a topic of debate).[15] Ultimately it was the Hungarian coach that generated a greater buzz of conversation than the chariot branlant of France because it was a much smoother ride.[15] Henceforth, the Hungarian coach spread across Europe rather quickly, in part due to Ippolito d'Este of Ferrara (1479–1529), nephew of Mathias' queen Beatrix of Aragon, who as a very junior Archbishopric of Esztergom developed a liking of Hungarian riding and took his carriage and driver back to Italy.[16] Around 1550 the 'coach' made its appearance throughout the major cities of Europe, and the new word entered the vocabulary of all their languages.[17] However, the new 'coach' seems to have been a concept (fast road travel for men) as much as any particular type of vehicle, and there is no obvious change that accompanied the innovation. As it moved throughout Europe in the late 16th century, the coach's body structure was ultimately changed, from a round-top to the 'four-poster' carriages that became standard by c.1600.[10]

Later development of the coach

The coach had doors in the side, with an iron step protected by leather that became the "boot" in which servants might ride. The driver sat on a seat at the front, and the most important occupant sat in the back facing forwards. The earliest coaches can be seen at Veste Coburg, Lisbon, and the Moscow Kremlin, and they become a commonplace in European art. It was not until the 17th century that further innovations with steel springs and glazing took place, and only in the 18th century, with better road surfaces, was there a major innovation with the introduction of the steel C-spring.[18]

It was not until the 18th century that steering systems were truly improved. Erasmus Darwin was a young English doctor who was driving a carriage about 10,000 miles a year to visit patients all over England. Darwin found two essential problems or shortcomings of the commonly used light carriage or Hungarian carriage. First, the front wheels were turned by a pivoting front axle, which had been used for years, but these wheels were often quite small and hence the rider, carriage and horse felt the brunt of every bump on the road. Secondly, he recognized the danger of overturning.

A pivoting front axle changes a carriage's base from a rectangle to a triangle because the wheel on the inside of the turn is able to turn more sharply than the outside front wheel. Darwin proposed to fix these insufficiencies by proposing a principle in which the two front wheels turn about a centre that lies on the extended line of the back axle. This idea was later patented as Ackermann steering. Darwin argued that carriages would then be easier to pull and less likely to overturn.

Carriage use in North America came with the establishment of European settlers. Early colonial horse tracks quickly grew into roads especially as the colonists extended their territories southwest. Colonists began using carts as these roads and trading increased between the north and south. Eventually, carriages or coaches were sought to transport goods as well as people. As in Europe, chariots, coaches and/or carriages were a mark of status. The tobacco planters of the South were some of the first Americans to use the carriage as a form of human transportation. As the tobacco farming industry grew in the southern colonies so did the frequency of carriages, coaches and wagons. Upon the turn of the 18th century wheeled vehicle use in the colonies was at an all-time high. Carriages, coaches and wagons were being taxed based on the number of wheels they had. These taxes were implemented in the South primarily as the South had superior numbers of horses and wheeled vehicles when compared to the North. Europe, however, still used carriage transportation far more often and on a much larger scale than anywhere else in the world.

Carriages and coaches began to disappear as use of steam propulsion began to generate more and more interest and research. Steam power quickly won the battle against animal power as is evident by a newspaper article written in England in 1895 entitled "Horseflesh vs. Steam".[19] The article highlights the death of the carriage as the means of transportation.

Nowadays, carriages are still used for day-to-day transport in the United States by some minority groups such as the Amish. They are also still used in the tourism as vehicles for sightseeing in cities such as Bruges, Vienna, New Orleans, and Little Rock, Arkansas.

The most complete working collection of carriages can be seen at the Royal Mews in London where a large selection of vehicles is in regular use. These are supported by a staff of liveried coachmen, footmen and postillions. The horses earn their keep by supporting the work of the Royal Household, particularly during ceremonial events. Horses pulling a large carriage known as a "covered brake" collect the Yeoman of the Guard in their distinctive red uniforms from St James's Palace for Investitures at Buckingham Palace; High Commissioners or Ambassadors are driven to their audiences with The Queen in landaus; visiting heads of state are transported to and from official arrival ceremonies and members of the Royal Family are driven in Royal Mews coaches during Trooping the Colour, the Order of the Garter service at Windsor Castle and carriage processions at the beginning of each day of Royal Ascot.

Construction

Body

Carriages may be enclosed or open, depending on the type.[20] The top cover for the body of a carriage, called the head or hood, is often flexible and designed to be folded back when desired. Such a folding top is called a bellows top or calash. A hoopstick forms a light framing member for this kind of hood. The top, roof or second-story compartment of a closed carriage, especially a diligence, was called an imperial. A closed carriage may have side windows called quarter lights (British) as well as windows in the doors, hence a "glass coach". On the forepart of an open carriage, a screen of wood or leather called a dashboard intercepts water, mud or snow thrown up by the heels of the horses. The dashboard or carriage top sometimes has a projecting sidepiece called a wing (British). A foot iron or footplate may serve as a carriage step.

A carriage driver sits on a box or perch, usually elevated and small. When at the front it is known as a dickey box, a term also used for a seat at the back for servants. A footman might use a small platform at the rear called a footboard or a seat called a rumble behind the body. Some carriages have a moveable seat called a jump seat. Some seats had an attached backrest called a lazyback.

The shafts of a carriage were called limbers in English dialect. Lancewood, a tough elastic wood of various trees, was often used especially for carriage shafts. A holdback, consisting of an iron catch on the shaft with a looped strap, enables a horse to back or hold back the vehicle. The end of the tongue of a carriage is suspended from the collars of the harness by a bar called the yoke. At the end of a trace, a loop called a cockeye attaches to the carriage.

In some carriage types the body is suspended from several leather straps called braces or thoroughbraces, attached to or serving as springs.

Undercarriage

Beneath the carriage body is the undergear or undercarriage (or simply carriage), consisting of the running gear and chassis.[21] The wheels and axles, in distinction from the body, are the running gear. The wheels revolve upon bearings or a spindle at the ends of a bar or beam called an axle or axletree. Most carriages have either one or two axles. On a four-wheeled vehicle, the forward part of the running gear, or forecarriage, is arranged to permit the front axle to turn independently of the fixed rear axle. In some carriages a dropped axle, bent twice at a right angle near the ends, allows for a low body with large wheels. A guard called a dirtboard keeps dirt from the axle arm.

Several structural members form parts of the chassis supporting the carriage body. The fore axletree and the splinter bar above it (supporting the springs) are united by a piece of wood or metal called a futchel, which forms a socket for the pole that extends from the front axle. For strength and support, a rod called the backstay may extend from either end of the rear axle to the reach, the pole or rod joining the hind axle to the forward bolster above the front axle.

A skid called a drag, dragshoe, shoe or skidpan retards the motion of the wheels. A London patent of 1841 describes one such apparatus: "An iron-shod beam, slightly longer than the radius of the wheel, is hinged under the axle so that when it is released to strike the ground the forward momentum of the vehicle wedges it against the axle". The original feature of this modification was that instead of the usual practice of having to stop the carriage to retract the beam and so lose useful momentum the chain holding it in place is released (from the driver's position) so that it is allowed to rotate further in its backwards direction, releasing the axle. A system of "pendant-levers" and straps then allows the beam to return to its first position and be ready for further use.[22]

A catch or block called a trigger may be used to hold a wheel on an incline.

A horizontal wheel or segment of a wheel called a fifth wheel sometimes forms an extended support to prevent the carriage from tipping; it consists of two parts rotating on each other about the kingbolt or perchbolt above the fore axle and beneath the body. A block of wood called a headblock might be placed between the fifth wheel and the forward spring.

Fittings

Many of these fittings were carried over to horseless carriages and evolved into the modern elements of automobiles. During the Brass Era they were often the same parts on either type of carriage (i.e., horse-drawn or horseless).

- Upholstery (trimming): traditionally similar to the upholstery of furniture; evolved into car interior ulholstery such as car seats and door trim panels

- Carriage lamps: typically oil lamps for centuries, although carbide lamps and battery-powered electric lamps were also used in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; evolved into car headlamps

- Trunk: a luggage trunk serving the same purpose as, and which gave its name to, later car trunks

- Toolbox: a small box with enough hand tools to make simple repairs on the roadside

- Blankets: in winter, blankets for the driver and passengers and often horse blankets as well

- Running board: a step to assist in climbing onto the carriage and also sometimes a place for standing passengers

- Shovel: useful for mud and snow in the roadway, to free the carriage from being stuck; was especially important in the era when most roads were dirt roads, often with deep ruts

- Buggy whip or coachwhip: whips for the horses. For obvious reasons, this is one of the components of carriage equipment that did not carry over from horse-drawn carriages to horseless carriages, and that fact has made such whips one of the prototypical or stereotypical examples of products whose manufacture is subject to disruptive innovation

Carriage terminology

A person whose business was to drive a carriage was a coachman. A servant in livery called a footman or piquer formerly served in attendance upon a rider or was required to run before his master's carriage to clear the way. An attendant on horseback called an outrider often rode ahead of or next to a carriage. A carriage starter directed the flow of vehicles taking on passengers at the curbside. A hackneyman hired out horses and carriages. When hawking wares, a hawker was often assisted by a carriage.

Upper-class people of wealth and social position, those wealthy enough to keep carriages, were referred to as carriage folk or carriage trade.

Carriage passengers often used a lap robe as a blanket or similar covering for their legs, lap and feet. A buffalo robe, made from the hide of an American bison dressed with the hair on, was sometimes used as a carriage robe; it was commonly trimmed to rectangular shape and lined on the skin side with fabric. A carriage boot, fur-trimmed for winter wear, was made usually of fabric with a fur or felt lining. A knee boot protected the knees from rain or splatter.

A horse especially bred for carriage use by appearance and stylish action is called a carriage horse; one for use on a road is a road horse. One such breed is the Cleveland Bay, uniformly bay in color, of good conformation and strong constitution. Horses were broken in using a bodiless carriage frame called a break or brake.

A carriage dog or coach dog is bred for running beside a carriage.

A roofed structure that extends from the entrance of a building over an adjacent driveway and that shelters callers as they get in or out of their vehicles is known as a carriage porch or porte cochere. An outbuilding for a carriage is a coach house, which was often combined with accommodation for a groom or other servants.

A livery stable kept horses and usually carriages for hire. A range of stables, usually with carriage houses (remises) and living quarters built around a yard, court or street, is called a mews.

A kind of dynamometer called a peirameter indicates the power necessary to haul a carriage over a road or track.

Competitive driving

In most European and English-speaking countries, driving is a competitive equestrian sport. Many horse shows host driving competitions for a particular style of driving, breed of horse, or type of vehicle. Show vehicles are usually carriages, carts, or buggies and, occasionally, sulkies or wagons. Modern high-technology carriages are made purely for competition by companies such as Bennington Carriages.[23] in England. Terminology varies: the simple, lightweight two- or four-wheeled show vehicle common in many nations is called a "cart" in the USA, but a "carriage" in Australia.

Internationally, there is intense competition in the all-round test of driving: combined driving, also known as horse-driving trials, an equestrian discipline regulated by the Fédération Équestre Internationale (International Equestrian Federation) with national organizations representing each member country. World championships are conducted in alternate years, including single-horse, horse pairs and four-in-hand championships. The World Equestrian Games, held at four-year intervals, also includes a four-in-hand competition.

For pony drivers, the World Combined Pony Championships are held every two years and include singles, pairs and four-in-hand events.

Types of horse-drawn carriages

An almost bewildering variety of horse-drawn carriages existed. Arthur Ingram's Horse Drawn Vehicles since 1760 in Colour lists 325 types with a short description of each. By the early 19th century one's choice of carriage was only in part based on practicality and performance; it was also a status statement and subject to changing fashions. The types of carriage included the following:

- Araba

- Bandy

- Barouche

- Berlin

- Brake

- Britzka

- Brougham

- Buckboard

- Buggy

- Cabriolet

- Calash

- Cape cart

- Cariole

- Carryall

- Chaise

- Chariot

- Clarence

- Coach

- Coupé

- Croydon

- Curricle

- Dogcart

- Dos-à-dos

- Drag

- Driving (horse)

- Droshky (Drozhki)

- Ekka

- Fiacre

- Fly

- Four-in-hand

- Gharry

- Gig

- Gladstone

- Governess cart

- Hackney

- Hansom

- Hearse

- Herdic

- Horse and buggy

- Horsebus

- Jaunting car

- Jingle

- Kalesa Filipino carriage

- Karozzin (Maltese horse carriage)[24]

- Kibitka

- Landau

- Limousine

- Mail coach

- One-horse carriage

- One-horse shay

- Park Drag

- Phaeton

- Spider phaeton

- Post chaise

- Randem

- Ratha

- Road Coach

- Rockaway

- Sociable

- Sprung cart

- Stagecoach

- Stanhope

- Sulky

- Surrey

- Tarantass (Tarantas)

- Tanga/Tonga (Indian horse carriage)

- Telega

- Tilbury

- Trap

- Troika

- Un-sprung cart

- Vardo (Romani wagon)

- Victoria

- Village cart

- Vis-à-vis

- Voiturette

- Volante

- Wagonette

- Whim

- Whiskey

Carriage collections

Australia

- Cobb + Co Museum – National Carriage Collection, Queensland Museum, Toowoomba, Queensland.[26]

- The National Trust of Australia (Victoria) Carriage Collection

Austria

- Museum of Carriages and Department of Court Uniforms, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.[27]

Belgium

Brazil

- National Historical Museum in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- Imperial Museum in Petrópolis, Brazil

Canada

- The Remington Carriage Museum in Cardston, Alberta, Canada

- The Campbell Carriage Factory Museum in Sackville, New Brunswick, Canada

- Kings Landing Historical Settlement in Prince William, New Brunswick, Canada, has a large collection of horse and oxen drawn vehicles.

Denmark

- Royal Carriage Museum, Christiansborg Palace, Copenhagen

- Slesvigske Vognsamling, Haderslev

Egypt

France

- Palace of Versailles

- The Versailles Stables[29]

Germany

- Marstallmuseum of Carriages and Sleighs in the former Royal Stables, Nymphenburg Palace, Munich[30]

- Hesse Museum of Carriages and Sleighs in Lohfelden near Kassel[31]

Italy

- Museo "Le Carrozze d'Epoca", Rome.

- Museo Civico delle Carrozze d'Epoca di Codroipo.

- Museo Civico delle Carrozze d'Epoca, San Martino, Udine.

- Museo della Carrozza di Macerata.

- Museo delle Carrozze del Quirinale, Rome.

- Museo delle Carrozze di Palazzo Farnese, Piacenza.

- Museo delle Carrozze, Catanzaro.

- Museo delle Carrozze, Naples.

Portugal

- National Coach Museum (Museu dos Coches), Lisbon[33]

- Geraz do Lima Carriage museum

Spain

- Carriage Museum, Seville

United Kingdom

- Mossman Collection, Luton, Bedfordshire[34]

- Royal Mews at Buckingham Palace, London.[35]

- Swingletree Carriage Collection. John Parker Swingletree Carriage Driving, Swingletree, Wingfield, Nr. Diss, Norfolk[36]

- National Trust Carriage Museum, Arlington Court, near Barnstaple, Devon[37]

- The Tyrwhitt-Drake Museum of Carriages, Maidstone, Kent[38]

United States

- Florida Carriage Museum, Weirsdale, Florida. Formerly Austin Carriage Museum.[39]

- Skyline Farm Carriage Museum, North Yarmouth, Maine[40]

- The Carriage Collection of the Owls Head Transportation Museum, Owls Head, Maine.[41]

- The Carriage Museum, Washington, Kentucky[42]

- Carriage Museum of America, Lexington, Kentucky[43]

- Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, Michigan[44]

- The Long Island Museum of American Art, History & Carriages, Stony Brook, New York

- Pioneer Village, Farmington, Utah.[45]

- Thrasher Carriage Museum, Frostburg, Maryland[46]

- The Wesley W. Jung Carriage Museum, Greenbush, Wisconsin[47]

- Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont

- Forney Museum of Transportation, Denver, Colorado[48]

- Mifflinburg Buggy Museum, Mifflinburg, PA. Only museum in US that preserves an original intact 19th century carriage factory.[49]

- Frick Art & Historical Center Car & Carriage Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, preserving carriages owned by Henry Clay Frick and his family.[50]

See also

- Horse-drawn vehicle

- Horsecar

- Horse harness

- Driving (horse)

- Horseless carriage (term for early automobiles)

- Howdah (carriage positioned on the back of an elephant or camel)

- Wagon

- War wagon

Notes

- Tarr, Laszlo. The History of the Carriage. Arco Pub. Co, 1969.

- Piggott, Stuart. Wagon, Chariot and Carriage: Symbol the Status in the History of Transport. Thames and Hudson, London, 1992

- Oxford English Dictionary 1933: Car, Carriage

- Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1855). "On False Etymologies". Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 71.

- Raimund Karl (2003). "Überlegungen zum Verkehr in der eisenzeitlichen Keltiké" [Deliberations on Traffic in the Ironage Celtic Culture] (PDF) (in German). Universität Wien. Archived from the original (.PDF) on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Stuart Piggott, The Earliest Wheeled Transport (1983); C.F.E Pare, Wagons and Wagon-Graves of the Early Iron Age in Central Europe. (Oxford, 1992).

- Piggott, Stuart (1970). "Copper Vehicle-Models in the Indus Civilization". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2 (2): 200–202. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00128394. JSTOR 25203212.

- Tarr, László (1969). The history of the carriage. Arco Pub. Co.

earliest carriage was the chariot,used in Mesopotamia in 1900 BC.

- Jochen Garbsch (June 1986). "Restoration of a Roman travelling wagon and of a wagon from the Hallstadt bronze culture" (in German). Leibniz-Rechenzentrum München. Archived from the original (.HTML) on 24 April 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Munby, Julian (2008), "From Carriage to Coach: What Happened?", in Bork, Robert; Kahn, Andrea (eds.), The Art, Science, and Technology of Medieval Travel, Ashgate, pp. 41–53

- Léon marquis De Laborde. Glossaire français du Moyen Age. Labitte, Paris, 1872. p. 208.

- Munby, Julian (2008), "From Carriage to Coach: What Happened?", in Bork, Robert; Kahn, Andrea (eds.), The Art, Science, and Technology of Medieval Travel, Ashgate, p. 45

- Baofu, Peter. The Future of Post-Human Transportation'. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012. p. 263.

- Coach. Oxford English Dictionary (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. 1933.

- Baofu, Peter. The Future of Post-Human Transportation. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012, p. 264.

- Munby, Julian (2008), "From Carriage to Coach: What Happened?", in Bork, Robert; Kahn, Andrea (eds.), The Art, Science, and Technology of Medieval Travel, Ashgate, p. 51

- Etymology for Coach in Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition. Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Baofu, Peter. The Future of Post-Human Transportation'.' Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012, p. 264.

- Mechanical Road Carriages: Horseflesh V. Steam. The British Medical Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1823 (7 December 1895), pp. 1434–1435. BMJ Publishing Group

- "Horse Carriage Parts Horse Drawn Vehicle". Great Northern Livery Company, Inc. 30 October 2003. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- "Basic Carriage Gear Horse Drawn Vehicles". Great Northern Livery Company, Inc. 2 November 2003. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- Patent 9020, 7 July 1841, awarded to Thomas Fuller, a coach-builder of Bath

- "Bennington Carriages homepage".

- Karozzin

- Alejandro, Campitelli. "MUHFIT – Museo Hístorico Fuerte Independencia Tandil". museodelfuerte.org.ar. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- Museum, c=AU; co=Queensland Government; ou=Queensland. "National Carriage Collection". www.cobbandco.qm.qld.gov.au. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Museum of Carriages and Department of Court Uniforms

- VZW Rijtuigmuseum Bree

- "The Versailles Stables". Archived from the original on 22 December 2004. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Museum of Carriages and Sleighs

- "kutschenmuseum.de". www.kutschenmuseum.de. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Nationaal Rijtuigmuseum Archived 19 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "NCM – Collection". Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Mossman Collection Website Archived 22 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Royal Mews Archived 17 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "SWINGLETREE CARRIAGE COLLECTION". www.swingletree.co.uk. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- National Trust Carriage Museum Archived 21 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Tyrwhitt-Drake Museum of Carriages". Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "Florida Carriage Museum & Resort". Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "SkylineFarm". www.skylinefarm.org. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- The Carriage Collection of the Owls Head Transportation Museum Archived 15 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Carriage Museum". www.washingtonky.com. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "Carriage Museum of America". carriagemuseumlibrary.org. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Horse Drawn Vehicles Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Carriage Hall". Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "HugeDomains.com - ThrasherCarriage.com is for sale (Thrasher Carriage)". www.hugedomains.com. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "Wade House - Wisconsin Historical Society - Home". Wade House. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "Forney Museum of Transportation". www.forneymuseum.org. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "Mifflinburg Buggy Museum". www.buggymuseum.org. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- The Frick Pittsburgh

Further reading

- Bean, Heike, & Sarah Blanchard (authors), Joan Muller (illustrator), Carriage Driving: A Logical Approach Through Dressage Training, Howell Books, 1992. ISBN 978-0-7645-7299-9

- Berkebile, Don H., American Carriages, Sleighs, Sulkies, and Carts: 168 Illustrations from Victorian Sources, Dover Publications, 1977. ISBN 978-0-486-23328-4

- Boyer, Marjorie Nice. "Mediaeval Suspended Carriages". Speculum, v34 n3 (July 1959): 359–366.

- Boyer, Marjorie Nice. Mediaeval Suspended Carriages. Cambridge, Mass.: The Mediaeval Academy of America, 1959. OCLC 493631378.

- Bristol Wagon Works Co., Bristol Wagon & Carriage Illustrated Catalog, 1900, Dover Publications, 1994. ISBN 978-0-486-28123-0

- Elkhart Manufacturing Co., Horse-Drawn Carriage Catalog, 1909 (Dover Pictorial Archives), Dover Publications, 2001. ISBN 978-0-486-41531-4

- Hutchins, Daniel D., Wheels Across America: Carriage Art & Craftsmanship, Tempo International Publishing Company, 1st edition, 2004. ISBN 978-0-9745106-0-6

- Ingram, Arthur, Horse Drawn Vehicles since 1760 in Colour, Blandford Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0-7137-0820-2

- King-Hele, Desmond. "Erasmus Darwin's Improved Design for Steering Carriages—And Cars". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, 56, no. 1 (2002): 41–62.

- Kinney, Thomas A., The Carriage Trade: Making Horse-Drawn Vehicles in America (Studies in Industry and Society), The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8018-7946-3

- Lawrence, Bradley & Pardee, Carriages and Sleighs: 228 Illustrations from the 1862 Lawrence, Bradley & Pardee Catalog, Dover Publications, 1998. ISBN 978-0-486-40219-2

- Museums at Stony Brook, The Carriage Collection, Museums, 2000. ISBN 978-0-943924-09-0

- Nelson Alan H. "Six-Wheeled Carts: An Underview". Technology and Culture, v13 n3 (July 1972): 391–416.

- Richardson, M. T., Practical Carriage Building, Astragal Press, 1994. ISBN 978-1-879335-50-9

- Ryder, Thomas (author), Rodger Morrow (editor), The Coson Carriage Collection at Beechdale, The Carriage Association of America, 1989. OCLC 21311481.

- Wackernagel, Rudolf H., Wittelsbach State and Ceremonial Carriages: Coaches, Sledges and Sedan Chairs in the Marstallmuseum Schloss Nymphenburg, Arnoldsche Verlagsanstalt GmbH, 2002. ISBN 978-3-925369-86-5

- Walrond, Sallie, Looking at Carriages, J. A. Allen & Co., 1999. ISBN 978-0-85131-552-2

- Ware, I. D., Coach-Makers' Illustrated Hand-Book, 1875: Containing Complete Instructions in All the Different Branches of Carriage Building, Astragal Press, 2nd edition, 1995. ISBN 978-1-879335-61-5

- Westermann, William Linn. "On Inland Transportation and Communication in Antiquity". Political Science Quarterly, v43 n3 (September 1928): 364–387.

- "Colonial Roads and Wheeled Vehicles". The William and Mary Quarterly, v8 n1 (July 1899): 37–42. OCLC 4907170562.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carriages. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Carriage. |

- 19th century American carriages: Their manufacture, decoration and use. By Museums at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY, 1987. Long Island Digital Books Project, CONTENTdm Collection, Stony Brook University, Southampton, New York.

- 19th Century Transportation-Carriages. University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

- All About Romance Novels – Carriages in Regency & Victorian Times.

- Appendix to Cadillac "Styling" section (coaching terminology). The Classic Car-Nection: Yann Saunders, Cadillac Database. Drawings and text

- CAAOnline: Carriage Tour Carriage Association of America. Photos and text.

- Calisphere – A World of Digital Resources. Search carriage. University of California. Hundreds of photos.

- Carriage House and Carriage parts. ThinkQuest Library. Illustrations and text.

- Colonial Carriage Works – America's Finest Selection of Horse Drawn Vehicles. Columbus, Wisconsin.

- Driving for Pleasure, Or The Harness Stable and its Appointments by Francis Underhill, 1896. Carnegie Mellon University. A comprehensive overview, with photographs of horse-drawn carriages in use at the turn of the 19th century. Full text free to read, with free full text search.

- An Encyclopædia of Domestic Economy, Comprising Subjects Connected with the Interests of Every Individual..., by Thomas Webster and William Parkes, 1855. Book XXIII, Carriages. Google Book Search.

- English Pleasure Carriages: Their Origin, History, Varieties, Materials, Construction, Defects, Improvements, and Capabilities: With an Analysis of the Construction of Common Roads and Railroads, and the Public Vehicles Used on Them; Together with Descriptions of New Inventions by William Bridges Adams, 1837. Google Book Search.

- Four wheeled vehicles. The Guild of Model Wheelwrights.

- Galaxy of Images | Smithsonian Institution Libraries. Carriages and sleighs.

- Georgian Index – Carriages. Georgian Index. Illustrations and text.

- The History of Coaches, by George Athelstane Thrupp, 1877. Google Book Search.

- Horse-drawn Transportation Clipart etc. Educational Technology Clearinghouse, University of South Florida. Drawings.

- JASNA Northern California Region. Jane Austen Society of North America. Illustrations and text.

- The Kinross Carriageworks, Stirling (Scotland), 1802–1966.

- Lexique du cheval! Lexikon of Carriage driving.

- Modern carriages, by W. Gilbey, 1905. The University of Hong Kong Libraries, China–America Digital Academic Library (CADAL).

- Passenger Vehicles The Guild of Model Wheelwrights. Illustrations and text.

- Science and Society Picture Library – Search Illustrations and text.

- Treatise on Carriages. Comprehending Coaches, Chariots, Phaetons, Curricles, Whiskeys, &c. Together with Their Proper Harness. In Which the Fair Prices of Every Article are Accurately Stated, by William Felton, coachmaker, 1794. Google Book Search.

- TTM web Texas Transportation Museum, San Antonio. Photos and text.

- Wheeled vehicles. The New York Times, 29 October 1871, page 2.