Captain Swing

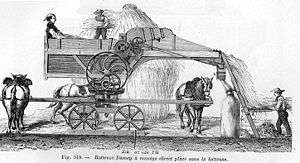

"Captain Swing" was the name appended to several threatening letters during the rural English Swing Riots of 1830, when labourers rioted over the introduction of new threshing machines and the loss of their livelihoods. Captain Swing was described as a hard-working tenant farmer driven to destitution and despair by social and political change in the early 19th century.

Swing riots

Popular protests by farm workers occurred across a wide swath of agricultural England, from Sussex in the south to Kent in the east,[1] and they had a number of structural causes. The main targets for protesting crowds were landowners/landlords, whose threshing machines they destroyed or dismantled, and whom they petitioned for a rise in wages. They also demanded contributions of food, money, beer, or all three from their victims. Often they sought to enlist local parish officials and occasionally magistrates to raise levels of poor relief as well. Throughout England, 644 rioters were imprisoned, 505 transported to Australia, and 19 were executed.[2]

The protests were notable for their discipline and the customary protocols favoured by the crowds, characteristics which were very much part of the tradition of popular protest going back to the eighteenth century. The structural reasons for the Swing "riots" (or risings) are relatively straightforward: underemployment, low wages, low levels of relief, and competition for winter employment from machinery.

For most contemporaries, the riotous but largely bloodless actions of the crowds presented less cause for alarm than the high incidence of arson during the period of Swing (October to December 1830). Swing the rick burner was not only more destructive, but much harder to apprehend than the rioters in this heightened atmosphere of tension and hostility. The relationship between arsonists and protesters is difficult to assess – although there is little doubt that a relationship existed. Whatever the immediate motivations of the arsonists of 1830 and 1831, their actions undoubtedly gave added strength to the demands of the protesting crowds.

Many protestors found sympathy in middle-class radicals who encouraged protesters to spread far from their original sources. Early sentences by magistrates against the rioters, even those who destroyed threshing machines, were fairly light; riots continued into 1831.

Examples of threatening "Swing" letters

Sir, Your name is down amongst the Black hearts in the Black Book and this is to advise you and the like of you, who are Parson Justasses, to make your wills. Ye have been the Blackguard Enemies of the People on all occasions, Ye have not yet done as ye ought,... Swing.

Sir, This is to acquaint you that if your threshing machines are not destroyed by you directly we shall commence our labours. Signed on behalf of the whole... Swing.[3]

Cultural references

- Swing is portrayed as an actual person in the alternative reality novel The Difference Engine.

- Captain Swing is a 1989 album by singer-songwriter Michelle Shocked.

- A character named "Findthee Swing" is a captain in the Ankh-Morpork "Unmentionables" secret police in Terry Pratchett's novel Night Watch.

- Captain Swing & The Electrical Pirates Of Cindery Island is a graphic novel by Warren Ellis, featuring a Captain Swing with advanced electrical technology and a flying boat.

- The stage play Captain Swing by Peter Whelan, directed by Bill Alexander, was produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1979.[4]

See also

- General Ludd

- Rebecca Riots

- Captain Rock

References

- Charlsworth, Andrew (1983). An Atlas of Rural Protest in Britain, 1548–1900. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 151.

- http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/politics/g5/

- From E. J. Hobsbawm and George Rudé, Captain Swing

- Coveney, Michael (10 July 2014). "Peter Whelan obituary". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077.

Further reading

- Hobsbawm, Eric & George Rudé. Captain Swing, 1969.

- Matthews, Mike. Captain Swing in Sussex and Kent, 2006.

- Rudé, George. The Crowd in History, Chapter 10, 'Captain Swing' and 'Rebecca's Daughters'. (Serif, London, 2005).

External links

- "Captain Swing recruits a Mansfield vicar" article from 1831 in The Manchester Guardian newspaper.