Cantor's diagonal argument

In set theory, Cantor's diagonal argument, also called the diagonalisation argument, the diagonal slash argument or the diagonal method, was published in 1891 by Georg Cantor as a mathematical proof that there are infinite sets which cannot be put into one-to-one correspondence with the infinite set of natural numbers.[1][2]:20–[3] Such sets are now known as uncountable sets, and the size of infinite sets is now treated by the theory of cardinal numbers which Cantor began.

The diagonal argument was not Cantor's first proof of the uncountability of the real numbers, which appeared in 1874.[4][5] However, it demonstrates a general technique that has since been used in a wide range of proofs,[6] including the first of Gödel's incompleteness theorems[2] and Turing's answer to the Entscheidungsproblem. Diagonalization arguments are often also the source of contradictions like Russell's paradox[7][8] and Richard's paradox.[2]:27

Uncountable set

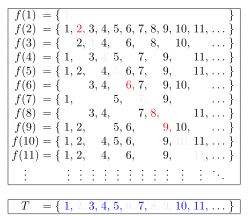

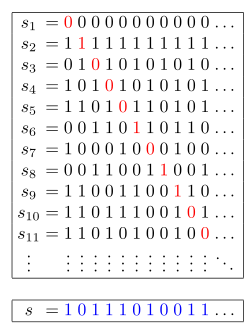

In his 1891 article, Cantor considered the set T of all infinite sequences of binary digits (i.e. each digit is zero or one). He begins with a constructive proof of the following theorem:

- If s1, s2, … , sn, … is any enumeration of elements from T, then there is always an element s of T which corresponds to no sn in the enumeration.

The proof starts with an enumeration of elements from T, for example:

s1 = (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...) s2 = (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, ...) s3 = (0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, ...) s4 = (1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, ...) s5 = (1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, ...) s6 = (0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, ...) s7 = (1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, ...) ...

Next, a sequence s is constructed by choosing the 1st digit as complementary to the 1st digit of s1 (swapping 0s for 1s and vice versa), the 2nd digit as complementary to the 2nd digit of s2, the 3rd digit as complementary to the 3rd digit of s3, and generally for every n, the nth digit as complementary to the nth digit of sn. For the example above, this yields:

s1 = (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...) s2 = (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, ...) s3 = (0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, ...) s4 = (1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, ...) s5 = (1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, ...) s6 = (0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, ...) s7 = (1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, ...) ... s = (1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, ...)

By construction, s differs from each sn, since their nth digits differ (highlighted in the example). Hence, s cannot occur in the enumeration.

Based on this theorem, Cantor then uses a proof by contradiction to show that:

- The set T is uncountable.

The proof starts by assuming that T is countable. Then all its elements can be written as an enumeration s1, s2, ... , sn, ... . Applying the previous theorem to this enumeration produces a sequence s not belonging to the enumeration. However, this contradicts s being an element of T and therefore belonging to the enumeration. This contradiction implies that the original assumption is false. Therefore, T is uncountable.

Real numbers

The uncountability of the real numbers was already established by Cantor's first uncountability proof, but it also follows from the above result. To prove this, an injection will be constructed from the set T of infinite binary strings to the set R of real numbers. Since T is uncountable, the image of this function, which is a subset of R, is uncountable. Therefore, R is uncountable. Also, by using a method of construction devised by Cantor, a bijection will be constructed between T and R. Therefore, T and R have the same cardinality, which is called the "cardinality of the continuum" and is usually denoted by or .

An injection from T to R is given by mapping strings in T to decimals, such as mapping t = 0111... to the decimal 0.0111.... This function, defined by f (t) = 0.t, is an injection because it maps different strings to different numbers.

Constructing a bijection between T and R is slightly more complicated. Instead of mapping 0111... to the decimal 0.0111..., it can be mapped to the base b number: 0.0111...b. This leads to the family of functions: fb (t) = 0.tb. The functions f b(t) are injections, except for f 2(t). This function will be modified to produce a bijection between T and R.

| Construction of a bijection between T and R |

|---|

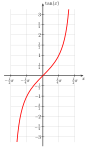

The function h: (0,1) → (−π/2,π/2) The function tan: (−π/2,π/2) → R This construction uses a method devised by Cantor that was published in 1878. He used it to construct a bijection between the closed interval [0, 1] and the irrationals in the open interval (0, 1). He first removed a countably infinite subset from each of these sets so that there is a bijection between the remaining uncountable sets. Since there is a bijection between the countably infinite subsets that have been removed, combining the two bijections produces a bijection between the original sets.[9] Cantor's method can be used to modify the function f 2(t) = 0.t2 to produce a bijection from T to (0, 1). Because some numbers have two binary expansions, f 2(t) is not even injective. For example, f 2(1000…) = 0.1000...2 = 1/2 and f 2(0111…) = 0.0111...2 = 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + … = 1/2, so both 1000... and 0111... map to the same number, 1/2. To modify f2 (t), observe that it is a bijection except for a countably infinite subset of (0, 1) and a countably infinite subset of T. It is not a bijection for the numbers in (0, 1) that have two binary expansions. These are called dyadic numbers and have the form m / 2n where m is an odd integer and n is a natural number. Put these numbers in the sequence: r = (1/2, 1/4, 3/4, 1/8, 3/8, 5/8, 7/8, ...). Also, f2 (t) is not a bijection to (0, 1) for the strings in T appearing after the binary point in the binary expansions of 0, 1, and the numbers in sequence r. Put these eventually-constant strings in the sequence: s = (000..., 111..., 1000..., 0111..., 01000..., 00111..., 11000..., 10111..., ...). Define the bijection g(t) from T to (0, 1): If t is the nth string in sequence s, let g(t) be the nth number in sequence r ; otherwise, g(t) = 0.t2. To construct a bijection from T to R, start with the tangent function tan(x), which is a bijection from (−π/2, π/2) to R (see the figure shown on the right). Next observe that the linear function h(x) = πx – π/2 is a bijection from (0, 1) to (−π/2, π/2) (see the figure shown on the left). The composite function tan(h(x)) = tan(πx – π/2) is a bijection from (0, 1) to R. Composing this function with g(t) produces the function tan(h(g(t))) = tan(πg(t) – π/2), which is a bijection from T to R. |

General sets

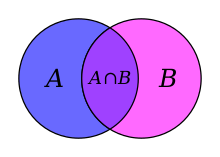

A generalized form of the diagonal argument was used by Cantor to prove Cantor's theorem: for every set S, the power set of S—that is, the set of all subsets of S (here written as P(S))—cannot be in bijection with S itself. This proof proceeds as follows:

Let f be any function from S to P(S). It suffices to prove f cannot be surjective. That means that some member T of P(S), i.e. some subset of S, is not in the image of f. As a candidate consider the set:

- T = { s ∈ S: s ∉ f(s) }.

For every s in S, either s is in T or not. If s is in T, then by definition of T, s is not in f(s), so T is not equal to f(s). On the other hand, if s is not in T, then by definition of T, s is in f(s), so again T is not equal to f(s); cf. picture. For a more complete account of this proof, see Cantor's theorem.

Consequences

Ordering of cardinals

Cantor defines an order relation of cardinalities, e.g. and , in terms of the existence of injections between the underlying sets, and . The argument in the previous paragraph then proved that sets such as are uncountable, which is to say .

Cantors diagonal argument together with the law of excluded middle, imply that . So, in the context of classical mathematics, the diagonal argument can be used to establish that, for example, although both sets under consideration are infinite, there are actually more infinite sequences of ones and zeros than there are natural numbers. This result then also implies that the notion of the set of all sets is inconsistent: If S were the set of all sets, then P(S) would at the same time be bigger than S and a subset of S. Assuming the law of excluded middle, every subcountable set (a property in terms surjections) is also already countable.

Constructive mathematics may dismiss a claims of existence via choice principles or claims of existence via double negation elimination, the rejection of the possibility of a rejection. Therefore, it is harder or impossible to order cardinals (and also ordinals) in a constructive set theory. For example, the Schröder–Bernstein theorem requires the law of excluded middle. Note that the ordering on the reals (the standard ordering extending that of the rational numbers) is also not necessarily decidable. Neither are most properties of interesting classes of functions decidable, by Rice's theorem, i.e. the right set of counting numbers for the subcountable sets may not be recursive.

In a set theory, theories of mathematics are modeled. For example, in set theory, "the" set of real numbers is identified as a set that fulfills some axioms of real numbers. Various models have been studied, such as the Dedekind reals or the Cauchy reals. Weaker axioms mean less constraints and so allow for a richer class of models. Consequently, in an otherwise constructive context (law of excluded middle not taken as axiom), it is consistent to adopt non-classical axioms that contradict consequences of the law of excluded middle. For example, the uncountable space of functions may be asserted to be subcountable.[10] In such a context, the subcountability of the real numbers is possible, intuitively making for a thinner set of numbers than in other models.

Open questions

Motivated by the insight that the set of real numbers is "bigger" than the set of natural numbers, one is led to ask if there is a set whose cardinality is "between" that of the integers and that of the reals. This question leads to the famous continuum hypothesis. Similarly, the question of whether there exists a set whose cardinality is between |S| and |P(S)| for some infinite S leads to the generalized continuum hypothesis.

Diagonalization in broader context

Russell's Paradox has shown that naive set theory, based on an unrestricted comprehension scheme, is contradictory. Note that there is a similarity between the construction of T and the set in Russell's paradox. Therefore, depending on how we modify the axiom scheme of comprehension in order to avoid Russell's paradox, arguments such as the non-existence of a set of all sets may or may not remain valid.

Analogues of the diagonal argument are widely used in mathematics to prove the existence or nonexistence of certain objects. For example, the conventional proof of the unsolvability of the halting problem is essentially a diagonal argument. Also, diagonalization was originally used to show the existence of arbitrarily hard complexity classes and played a key role in early attempts to prove P does not equal NP.

Version for Quine's New Foundations

The above proof fails for W. V. Quine's "New Foundations" set theory (NF). In NF, the naive axiom scheme of comprehension is modified to avoid the paradoxes by introducing a kind of "local" type theory. In this axiom scheme,

- { s ∈ S: s ∉ f(s) }

is not a set — i.e., does not satisfy the axiom scheme. On the other hand, we might try to create a modified diagonal argument by noticing that

- { s ∈ S: s ∉ f({s}) }

is a set in NF. In which case, if P1(S) is the set of one-element subsets of S and f is a proposed bijection from P1(S) to P(S), one is able to use proof by contradiction to prove that |P1(S)| < |P(S)|.

The proof follows by the fact that if f were indeed a map onto P(S), then we could find r in S, such that f({r}) coincides with the modified diagonal set, above. We would conclude that if r is not in f({r}), then r is in f({r}) and vice versa.

It is not possible to put P1(S) in a one-to-one relation with S, as the two have different types, and so any function so defined would violate the typing rules for the comprehension scheme.

See also

- Cantor's first uncountability proof

- Controversy over Cantor's theory

- Diagonal lemma

References

- Georg Cantor (1891). "Ueber eine elementare Frage der Mannigfaltigkeitslehre". Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung. 1: 75–78. English translation: Ewald, William B. (ed.) (1996). From Immanuel Kant to David Hilbert: A Source Book in the Foundations of Mathematics, Volume 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 920–922. ISBN 0-19-850536-1.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Keith Simmons (30 July 1993). Universality and the Liar: An Essay on Truth and the Diagonal Argument. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43069-2.

- Rudin, Walter (1976). Principles of Mathematical Analysis (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 30. ISBN 0070856133.

- Gray, Robert (1994), "Georg Cantor and Transcendental Numbers" (PDF), American Mathematical Monthly, 101 (9): 819–832, doi:10.2307/2975129, JSTOR 2975129

- Bloch, Ethan D. (2011). The Real Numbers and Real Analysis. New York: Springer. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-387-72176-7.

- Sheppard, Barnaby (2014). The Logic of Infinity (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-107-05831-6. Extract of page 73

- "Russell's paradox". Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy.

- Bertrand Russell (1931). Principles of mathematics. Norton. pp. 363–366.

- See page 254 of Georg Cantor (1878), "Ein Beitrag zur Mannigfaltigkeitslehre", Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik, 84: 242–258. This proof is discussed in Joseph Dauben (1979), Georg Cantor: His Mathematics and Philosophy of the Infinite, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-34871-0, pp. 61–62, 65. On page 65, Dauben proves a result that is stronger than Cantor's. He lets "φν denote any sequence of rationals in [0, 1]." Cantor lets φν denote a sequence enumerating the rationals in [0, 1], which is the kind of sequence needed for his construction of a bijection between [0, 1] and the irrationals in (0, 1).

- Rathjen, M. "Choice principles in constructive and classical set theories", Proceedings of the Logic Colloquium, 2002